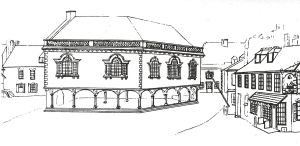

In May 1834, a meeting was called in what was then Dover’s town hall, in the Market Square. Headed by the Mayor – Joseph Webb Pilcher – and supported by one of Dover’s would be members of Parliament, John Minet Fector junior, along with several other dignities. The only item on the agenda was to bring the new fangled railway to Dover. It was proposed to continue the proposed Greenwich-Ashford Line to the town and Colonel Landmann, of the Greenwich Railway, addressed the assembled throng.

It was estimated that the total cost of the Line would be £1,300,000 and the length, 73-miles. There would be 38 stations conveying 520,000 passengers annually. At 2pence a mile, it was estimated that the revenue to the company would be £135,700 annually. Colonel Landmann then looked at the cost of passengers travelling from Dover to London – and visa versa – by the existing means of transport. These were the stagecoach and ship. He showed that against these forms of competition, a railway line was cheaper to the passenger and created more revenue for the operating company. In regards to the carriage of goods, notably fish where speed was of the essence, he again showed that railways were cheaper, more efficient and gave greater profits to the investors than the alternative means of transport. Colonel Landmann finished his talk by looking at the positive effects of the existing railways operating to Liverpool and Manchester.

The audience showed a great deal of interest but of particular concern was the route the line would take between Folkestone and Dover. Two alternatives were given; the first was from Cheriton, over the Canterbury Road near Uphill in Folkestone and then down the Alkham Valley to Kearsney and along the River Dour valley into Dover. The terminus would be in the vicinity of the Market Square. The second line was along the seashore from Folkestone to Dover with a terminus by the then harbour.

The meeting was rounded off by Dover’s Member of Parliament, John Fector, who called for a motion to bring the railway to Dover, saying that, ‘by carrying it into effect, the intercourse with France would be materially improved, and Dover would feel the good effects of a communication by which farmers and fishermen could expeditiously convey their goods to London markets.’ The motion was unanimously carried.

Two years later, in 1836, the South Eastern Railway Company (SER) took this decision further and asked Parliament for an Act to build a line from London to Dover. At the same time, the London and Brighton Railway Company were applying for an Act to build a railway. Given Royal Assent on 21 June 1836, both requests were juxtaposed into one Act stating that both companies were to use the same line from London Bridge to Redhill. This made the train journey to Dover 20-miles (32 km) longer than by stagecoach and added to the overall costs.

Albeit, from Redhill the line through Tonbridge to Ashford was (and still is) almost a straight line, while to Folkestone the company only required the building of two short tunnels. These two factors kept down costs but the decision on which way to take the Line from Folkestone to Dover still had to be made. The estimated overall cost was estimated at £3,000,000. A requirement of the Act was that 50% of the capital was to be raised before the project could go ahead. Objecting landowners, along the proposed line, used this aspect to protest against the project calling would be investors, ‘men of straw – all brag and no money’.

SER managed to raise the required capital and the decision was made to take the line from Folkestone to Dover along the seashore as the cheaper option. The engineer, William Cubitt (1785–1861), superintended the project and in November 1837 the contract was given to two Kentish firms for the excavation of the Shakespeare cliff for a tunnel. This was 1,331 yards (1,217 metres) long but the chalk was not as sound as first thought, hence two single-line tunnels 12-feet wide, 30-feet high and 10-foot apart were built. They are Gothic in style to lessen the pressure on the crowns of the arches. The tunnel was ventilated by seven shafts between 190-feet and 207-feet in length and seven galleries running out from the southern tunnel towards the sea. The southern and part of the northern tunnel were faced with brick.

A platform of earth, excavated from the tunnel was laid alongside Shakespeare beach to Archcliffe Tunnel that was also being excavated. At the time, Archcliffe Fort projected out to sea and the 50-yard tunnel (45.7 metres) was built under the Fort but later demolished. The Board of Ordnance, at the time of the excavation, stipulated that the tunnel should be able to be closed off at both ends in case of hostilities and that there should be loopholes for musketry defence in the retaining walls.

The contracts were being tendered for a seawall and it was decided that the track would be laid on a low-lying timber viaduct across the shingle close to the wall. However, the first attempt was washed away by the sea. On consideration, the company was forced to opt for the more expensive, ‘… heavy beams … against which waves would dash in vain, as its peculiar construction offered them no residence.’ Further west, from Folkestone in August 1842, the line was being laid towards Abbots Cliff going through Martello tunnel – 776 yards (710 metres) in length and Abbots Cliff tunnel – 1,904 yards (1,741metres).

By June 1842, the line from London had reached Folkestone, where stage coaches or post-chaise were provided for passengers to Dover. At the time, the company were seriously discussing making this a permanent arrangement and abandoning the line to Dover, as it was already proving costly. With this in mind they bought Folkestone harbour to provide a cross-Channel passage replacing the service at Dover. The folk of Dover were angered by this and Parliament was petitioned reminding them, and the company, of the Act and the need to comply. The SER argument for not proceeding centred on Round Down Cliff rising to a height of 375-feet above sea level. It was estimated by William Cubitt to average some 70-feet in thickness and was unstable so could not be tunnelled. The Company, however, was obliged to comply with the Act and Cubitt decided to ’blow’ the cliff out of the way using gunpowder. On the positive side, he said, the resultant chalk would provide a platform for the railway line.

The day chosen for the event was Thursday 26 January 1843 and ‘caution’ notices were distributed throughout Dover telling people to stay indoors or to watch at a respectful distance. It was expected that women would hide in their boudoirs, children would be kept indoors and only the bravest of men would climb to the top of the cliffs and watch.

In the event nearly every man, woman and child from Dover attended! Army personnel were obliged to put a cordon of rope tied to poles and carrying red and white flags along nearby cliff edges and across the cliffs closest to Round Down Cliff. Both police officers and army personnel patrolled the cordon.

At 10.00hrs, that morning, the Directors, having spent the night at the Ship Inn on Customs House Quay, Dover, went to view Shakespeare Tunnel. Then, having looked at Round Down Cliff from the shore proceeded by zigzag steps to the top. From there they were accompanied by senior army personnel under the command of General Sir Charles Pasley (1780–1861), to a large pavilion erected about 150-feet from the edge of the cliff. They were joined by local dignitaries, their wives and national celebrities, including, Sir John Frederick William Herschel, 1st Baronet, (1792– 1871), mathematician, astronomer and chemist, Adam Sedgwick (1785 –1873) one of the founders of modern geology and Sir George Biddell Airy (1801– 1892), Astronomer Royal 1835-1881.

The elite group were then taken through the expected sequence of events. Initially, there would be a series of small explosions followed, after 30-minutes, by the main explosion. Over this, Professor Sedgwick expressed concern that if there was a concealed fissure, one of the small explosions, ‘might throw it open.’ To which another member of the audience responded that if that were the case, then all those in the pavilion would be ‘swallowed up,’ Someone else added that they would ‘be swallowed down!’

The actual procedure was that a small arched tunnel some 300-feet in length and running east to west had been pierced through the bottom of Round Down Cliff. From this and at equal distances, three well-like shafts had been sunk from which three horizontal galleries had been excavated. At the end of each gallery was the gunpowder. The centre gallery contained 75 barrels and the eastern and western 55 barrels each. The 185 barrels equalled 18,500-lbs of gunpowder brought from Faversham Gunpowder Works. The placing of the gunpowder had been undertaken the previous Tuesday by Mr Hodges, the railway assistant engineer, and Corporal Rae of the Sappers and Miners. General Pasley and Lieutenant Hutchinson checked all was correct and then the galleries were sealed with tightly rammed chalk and sand. Lieutenant Hutchinson was an expert in creating simultaneous explosions and planned to use 3 sets of Daniel’s Tripel batteries to create ‘galvanic fire.’

At 09.00-hours on the morning of the event, a red flag was hoisted on Round Down Cliff. Lieutenant Hutchinson tested the wires using a galvanometer (an instrument for detecting or measuring an electric current by movements of a magnetic needle or of a coil in a magnetic field). The batteries were charged and there was a final run through of procedures. At 13.30hours, there was a discharge of half a dozen blasts on the face of Abbots Cliff creating a great sensation in the crowds. Then the multitude became silent before turning to each other uttering in dismay that nothing really had happened!

Everyone, excepting Lieutenant Hutchinson – who undertook to fire the central battery – the resident engineer, John Wright and the assistant engineer, Mr Hodges – who were taking charge of the western and eastern batteries – was asked to leave the Battery House. At 14.15hours the signal flags were hoisted and silence engulfed the multitude of onlookers. All that could be heard were a few crows and choughs. A few minutes later a single gun was fired and four minutes later two guns and the crowd started shouting ‘Now! Now!’

A lighted fuse was thrown over the cliff edge and at 14.26hrs, a dull, muffled boom could just be heard at the same time there was a heavy jolting movement of the earth. The bottom of the cliff, according to one bystander, ‘seemed to dissolve.’ Then the face of the cliff slowly sank giving way to clouds of chalk. This rotated as it made its way up the new cliff face and then fell back into what was, by this time, a fermenting, foaming sea. There was no loud explosion, smoke or fire and all that could be heard were the gasps of the audience.

In the Battery house there was disappointment for so quiet was the explosion that the three men thought they had failed. Then someone broke the silence by shouting, ‘Three cheers for the engineer!’ The whole assembled throng cheered for William Cubitt and the three knew that all had gone well!

The explosion removed a section of the cliff 300-feet long, 300-feet high and 70-feet thick amounting to some 400,000 cubic yards of chalk. A second blasting took place on 2 March and a third on 5 May with the final blasting on the 17 October. However, the final blast was not as successful as the others were. Altogether upwards 1,000,000 tons of cliff had been removed creating a shelf at sea level of about fifteen acres on which the line was built to Dover.

- Published:

- Dover Mercury: 30 January & 6 February 2014