In the foyer of Harbour House, Waterloo Crescent – the headquarters of Dover Harbour Board (DHB) – is the bell from the World War I (1914-1918) monitor ship Glatton. It is a reminder of a wartime catastrophe that was kept under wraps for the sake of the country’s moral.

The Glatton, a monitor, was originally built for the Norwegian Navy in January 1913, as one of eight coastal defence ships. In 1918, she was taken over by the Royal Navy and sent to Sir W G Armstrong Whitworth & Co Ltd, Newcastle-upon-Tyne for conversion into a new type of monitor warship. Monitors were designed for coastal bombardment, consequently they had a shallow draft and usually had two guns high up in the turret. At the refit, the Glatton, and her sister ship Gorgon, were fitted with two 9.2-inch guns in the turret and four 6-inch guns lower down. They were also fitted with blisters on the side of their hulls that could be filled with water. These were to provide additional stability when firing the guns and also protection against submarine attack.

The Glatton was commissioned on 31 August 1918 and on Friday 6 September was loaded with ammunition, depth charges and explosives. Her orders were to take soldiers across the Channel from Dover to France for the offensive and then to be part of the attack on the German held Belgium coast. On 9 September, before leaving North Shields, the Glatton underwent sea and gun trials and then left for Dover arriving on 12 September. By that time, there were other armoured monitors in the harbour, including the Gorgon. There were also several well-armed smaller ships all being assembled for the offensive.

On the morning of 16 September, the Glatton was some 500 yards from the shore and took on board 135-tons of coal from the collier Thornley. In the afternoon her 303-crew members were on board but early in the evening a large number left to enjoy Dover‘s entertainments including Captain Neston Diggle (1881-1963). Captain Diggle was a highly decorated Royal Navy officer.

The evening was quiet and those left on board were going about their business. Then suddenly, at 18.17hrs, there was a tremendous explosion. In Dover buildings shook and windows were broken. Many local folk thought that the Germans were shelling the town with heavy guns from ships close to the harbour and ran for shelter. Those who could distinguish between the sound of an explosion from gunfire guessed that it came from the harbour and made their way down to the Seafront. The news quickly spread that the Glatton had blown up and yellow flames (probably from burning cordite) were belching from her. Soon the Seafront was packed with spectators.

In the harbour, the Glatton was ablaze but within minutes of the explosion the DHB tugs, Lady Duncannon and Lady Brassey, were alongside. Both tugs were spraying water onto the blaze and as the skipper of the Lady Brassey, Captain W J Pearce, told reporters afterwards, ‘I ordered my men to get out the fire-fighting apparatus and we forced our way through the scorching, suffocating barrage of smoke and scrambled on the Glatton. Vague figures kept looming up – wounded men struggling to escape but everyone were now aware that at any moment the ship might blow up.’

Meanwhile, the remaining DHB tugs and dockyard tenders were towing other fully loaded monitors as far away from the burning vessel as possible. From the monitors and other ships in the harbour, lifeboats were launched and attempts were made to rescue as many as possible of the crew of the Glatton. The first of the survivors were landed on the Promenade Pier – at the time, renamed Naval Pier as it had been commandeered by the Royal Navy for the duration of the War. Some of the injured were able to walk to the shore end but they were all badly burnt and their clothing torn to pieces. Naval ambulances took the men to the Naval sickbays and the military hospital on Western Heights Injured were also taken to the hospital ship Liberty, berthed in the harbour.

As it was Wartime, the town was subject to military rule. The Admiral of the Port was Vice-Admiral Roger Keyes (1872-1945), who on 23 April 1918 had masterminded the successful Zeebrugge Raid. At the time of the Glatton accident he was about to attend a dinner in St Margaret’s Bay. On being told of catastrophe the Admiral immediately returned to Dover and twenty minutes later was running down Promenade Pier passing wounded men. From there, Keyes took a boat out to the Glatton and boarded her, where Captain Diggle met him. Both surveyed the extent of the damage at which time a white pall of smoke some 600-feet high hung over the ship. The Vice-Admiral was told that the explosion had occurred amidships. Keyes then returned to Admiralty House on Marine Parade.

Ratings on board the Glatton, many of them injured, volunteered to open the seacocks in the bow of the ship, in an attempt to flood the magazines. They were successful and the fire was extinguished in that part of the ship. All the tugs and dockyard tenders were playing water onto the blaze when suddenly the fire amidships flared up again. The dense smoke changed from white to black indicating that oil and fuel were burning and the fire was moving towards the stern of the vessel. In the magazines there, the remaining half of the ammunition was stored. Every vessel that could hose water was around the midship and stern of the Glatton but it was becoming obvious that the inferno could not be brought under control in time to prevent a massive explosion.

It was then that Keyes had to make the most important decision of his life.

Did he allow those fighting the fire to do their best and risk the Glatton blowing up?

If he took that option it could have a subsequent domino effect of causing other munitions ladened ships to blow up and, in the worst-case scenario, potentially thousands of deaths with the destruction of the town of Dover.

Alternatively, he could order the sinking of the Glatton even though there may be men still trapped on board.

Keyes contacted Mayor Edwin Farley, the local military and the harbour officials and appraised them of the situation and what he planned to do.

On the Vice-Admiral’s command the town’s air raid sirens were sounded and the police, who were then under council jurisdiction erected barriers across the town in line with the Market Square. Detachments of troops arrived from the Castle and Western Heights with rifles and bayonets, wearing steel helmets and gas masks. Their orders were to help the police shepherd the crowds from the Seafront, the streets behind and all the adjacent properties, to safety behind the barriers. The armed soldiers manned the barriers but most folk made their way up to Western Heights where they could see what was going on. On board the Glatton, Captain Diggle ensured that everyone, who could be found, dead or alive, was off the ship and he then left by the last boat. All of the vessels in the harbour pulled away from the Glatton to what was hoped were a safe distance.

Vice-Admiral Keyes, then ordered two destroyers to torpedo the Glatton.

At 19.50hrs the Cossack, a Tribal-class destroyer, aiming at a pre-selected vulnerable part on the starboard side (right, looking towards the bow), fired two 18-inch torpedoes one of which failed to explode. The ‘M’-class destroyer Myngs followed, firing two 14-inch torpedoes. When the three torpedoes exploded, smoke was driven up the Glatton’s funnels and the blaze roared with renewed vigour. As she was a monitor, the Glatton was almost flat bottomed and it was expected that she would heal-over. She did, but not as quick as had been anticipated – would she blow? At 20.10hrs the Glatton turned turtle, her port side(left) uppermost and started to sink in 40-foot of water. Much to the relief of all concerned.

Gravestones of Vice-Admiral Keyes and eight of the victims of the Glatton accident. St James Cemetery, Dover – AS 2015

During the following week the Secretary of the Admiralty issued the following statement: ‘One of His Majesty’s monitors was sunk in Dover harbour on September 16 as a result of an internal explosion. One officer and 19 men were killed by the explosion and 57 men are missing, presumed killed. All the next of kin have been informed.’

A prolonged investigation was undertaken and attempts were made to play down the disaster. The latter, it was believed, would be relatively easy because of the on going War on the Western Front and at sea, where the death and injury toll was high. Further, Spanish ‘Flu’ was taking its toll of civilians and armed forces personnel alike. Nonetheless, the cataclysmic extent of what had happen in Dover harbour on 16 September 1918 was beginning to emerge.

In early 1919, four Royal Navy Personnel received the Albert Medal for gallantry in saving life on board the Glatton. They were Lieutenant George Devereux Belben, D.S.C., R.N., Sub-Lieutenant David Hywel Evans, R.N.V.R. – who had taken part in the Zeebrugge Raid of April 1918 – P. O. Albert Ernest Stoker, O.N. 227692 and Able Seaman Edward Nunn, O.N. J.15703. Their citation began with a description of the disaster and goes on,

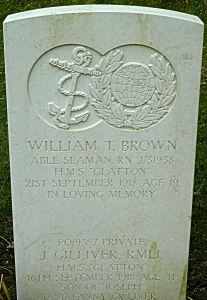

Gravestone of Seaman William T Brown d 21.09.1918 & Private J Gilliver d 16.09.1918 victims of the Glatton accident. St James Cemetery Dover. AS 2015

‘Efforts were made to extinguish the fire by means of salvage tugs. The foremost magazines were flooded, but it was found impossible to get to the aft magazine flooding positions. The explosion and fire cut off the aft part of the ship, killing or seriously injuring all the officers who were on board with one exception. The ship might have blown up at any moment. Lieutenant Belben, Sub-Lieutenant Evans, Petty Officer Stoker, and Able Seaman Nunn were in boats that were rescuing men who had been blown, or who had jumped, overboard. They proceeded on board H.M.S. Glatton on their own initiative, and entered the super-structure, which was full of dense smoke, and proceeded down to the deck below. Behaving with the greatest gallantry and contempt of danger, they succeeded in rescuing seven or eight badly injured men from the mess deck, in addition to fifteen whom they found and brought out from inside the superstructure. This work was carried out before the arrival of any gas masks, and, though at one time they were driven out by the fire, they proceeded down again after the hoses had been played on the flames. They continued until all chance of rescuing others had passed, and the ship was ordered to be abandoned, when she was sunk by torpedo, as the fire was spreading, and it was impossible to flood the aft magazines.

Admiralty, 31 January 1919

The one officer mentioned in the citation, who survived the initial blast, was the Ship’s doctor, Lieutenant Commander Edward Leicester Atkinson (1881-1929). Along with the four men, Captain Diggle said that he too deserved the Albert Medal. It was learnt, by the media, that the doctor had been blinded in the Glatton catastrophe. On investigation, they discovered that in 1912, Dr Atkinson had been the physician and parasitologist of Captain Robert Scott’s (1863-1912) ill-fated Terra Nova expedition to the South Pole.

Gravestones of an Unknown Sailor d 16.09.1918 & Cornelius Costello stoker d 17.09.1918 victims of the Glatton accident. St James Cemetery Dover. AS 2015

In the spring of 1919 the Court of Inquiry into the Glatton catastrophe was held and it was confirmed that the explosion had occurred in the midships magazine situated between the boiler and engine rooms. The magazine was insulated with 5 inches of cork covered by wood planking 0.75 inches thick and provided with special cooling equipment. Therefore, it was concluded, that it was unlikely that the cordite, which was speculated, had spontaneously combusted.

The magazines of Glatton’s sister ship Gorgon were examined and it was found that the red lead paint on the bulkhead of the midship magazine was blistered beneath the lagging. Tests indicated that it had been subjected to temperatures of at least 400º Fahrenheit (204º Celsius). Temperatures inside the magazine did not exceed 83º Fahrenheit (28º Celsius) and a test was carried out using red-hot ashes but this was inconclusive. However, further tests showed that the cork could give off flammable fumes under high heat and pressurized air. It was observed that on the Gorgon, that the stokers in the midship boiler room, were in the habit of piling the red-hot clinker and ashes from the boilers against the bulkhead directly adjoining the magazine. This was to allow the ashes to cool before they were sent up the ash ejector.

The Court concluded that the first explosion on the Glatton was caused by the slow combustion of the cork lagging of the midship magazine that led to the ignition of the magazine and then to the ignition of the cordite in it and so caused the explosion. They said that the cause was probably due to the clinker piled against a magazine bulkhead that ignited the cork insulation, starting a blaze that spread to the ammunition.

Gravestone of an Unknown Sailor d 16.09.1918 & J Spence 16.09.1918 victims of the Glatton accident. St James Cemetery Dover AS 2015

It was accepted, by the Court, that Vice-Admiral Keyes had made a difficult decision to torpedo the ship but had the fire reached the stern of the ship and the aft magazines then it was certain that the ammunition would have gone up. From then on there would have been a chain of explosions involving much of the shipping in the harbour and the result would have been a catastrophe involving a great loss of life. As for those still on board, the Inquiry stated that the ironwork of the ship was so hot that no one could have remained alive when the torpedoes struck the vessel.

Gravestone of two Unknown Sailors d 16.09.1918 victims of the Glatton accident. St James Cemetery, Dover – AS 2015

In May 1919, Surgeon Lieutenant Commander Edward Leicester Atkinson was awarded the Albert Medal. His citation starts with an account of the initial explosion on the Glatton and then says, ‘… The explosion and fire cut off the aft part of the ship, killing or seriously injuring all the officers on board with one exception. The ship might have blown up at any moment. At the time of the explosion, Surgeon Lieutenant Commander Atkinson was at work in his cabin. The first explosion rendered him unconscious. Recovering shortly, he found the flat outside his cabin was filled with dense smoke and fumes. He made his way to the quarterdeck by the means of a ladder in the warrant officers’ flat, the only one still intact. During this time, he brought two unconscious men on the upper deck, he himself being uninjured. He returned to the flat, and was bringing the third man up, when a small explosion occurred while he was on the ladder. This explosion blinded him, and, at the same time, a piece of metal was driven into his left leg in such a manner that he was unable to move until he himself extracted it. Placing the third man on the upper deck, he proceeded forward through the shelter deck. By feel, being unable to see, he here found two more unconscious men, both of whom he brought out. He was found later on the upper deck in an almost unconscious condition, so wounded and burnt that his life was despaired of for some time.’

Admiralty 20 May 1919

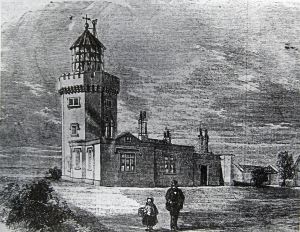

In the days that followed the loss of the Glatton, DHB’s Harbour Master, Captain John Iron speculated on the fate of the upturned hull and how it could be moved out of the fairway, used for shipping movements in the busy harbour. Dover harbour was still under the jurisdiction of the Admiralty who had their own harbour master in Dover with the title, King’s Harbour Master. Albeit, Captain Iron was Salvage Officer to the Admiralty and in his report he pointed out that the Glatton had sank in 40-feet of water close to the fairway and needed to be moved. A lighthouse was erected on her blister as a warning to shipping and the Admiralty estimated that the salvaging would cost about £60,000. Salvage companies were approached and representatives came to Dover. They looked, assessed the situation and all went away having said that it was impossible.

Nothing more was done, but on 12 July 1923, a legal action was brought by the owners of the yacht Magadalene against the King’s Harbour Master in Dover, for damages. The yacht had hit the wreck of the Glatton because, the yacht owners’ legal council alleged, it was insufficiently lighted. The Admiralty countered, saying that the wreck had a lighthouse on it and further, the yacht had no right to be in an Admiralty port. On the latter point the owners’ lost the claim. On 29 September that year, the Admiralty Harbour was handed back to the DHB and the Magadalene case left them vulnerable if another vessel hit the wreck. DHB invited 19 salvage companies to give estimates on salvaging the Glatton but only the Liverpool Salvage Association said that they could. Their price was £45,000 and having earned very little revenue since 1914, when the Admiralty took over the harbour, DHB could not afford it.

The only way DHB could raise sufficient revenue was to encourage the cruise industry to return to Dover but in the post-World War I years, Britain and Europe were in the grip of an economic depression. Further, since the Admiralty had taken over the harbour in 1914 there had been no attempt at dredging resulting in the loss of deep water. Therefore, the larger liners of the Hamburg American Line, that had previously come to Dover, could no longer call at the port. Captain Iron and his team had undertaken preliminary dredging but to make the harbour fully operational it was imperative to move the Glatton away from the fairway.

After deliberations the Chairman of DHB, Sir William Crundall, asked if Captain Iron could provide an estimate to move the Glatton. This he did and calculated that it would cost £5,000. The Captain later admitted that he had underestimated the amount of accumulated mud within the vessel that was to increase the overall cost of the salvaging. The work was scheduled to start on 18 May 1925, with a general survey undertaken by divers to ascertain the position and condition of Glatton. The divers went down and found that the ship was so encased in mud and silt that this had to be removed before they could make their survey. Using small explosive charges to break up the mud, DHB salvage vessel Dapper and tug Lady Brassey, with powerful centrifugal suction pumps, cleared away 12,000 tons of mud that had collected under the decks, between the port gunwale and the seabed.

The operation to remove the mud took several weeks to complete and then the survey was made. Divers Maddison, Bolson, and Matthews found that the Glatton had turned over to an angle of 66º and was resting on the barbette of the starboard six-inch gun, the upper edge of the boat deck and the top of the conning tower. Iron’s wrote later that, ‘The tripod mast, four feet in diameter, of half-inch steel, and the two struts, two feet in diameter, were found to be buckled into a V shape, but were not broken. To clear these away we had to cut them through with acetylene submarine cutting apparatus, and the strengthening bars inside had to be blown away with small charges. The funnel and the bridge had to be cut away by the same means, and everything cleared away that extended below the armour plated conning tower, which was then thirty-five feet below water at neap tides.’ (Captain Iron)

The next stage was to close all openings of the wreck making it airtight. This was undertaken by the divers who attached steel plates, including along the starboard side where the torpedoes had entered. The gun emplacements and the sight holes were also made as airtight as possible. Then eight pairs of nine-inch wire ropes were passed under the Glatton for which, in some places divers cut tunnels through the mud with water jets. Once this was accomplished, air was pumped into the Glatton by fitting a four-inch airpipe the entire length of the wreck, between the bulge and the shell plating. The airpipe had branch pipes going into as many of the ship’s compartments as possible.

As an experiment the Glatton was checked if she was airtight. This was done by pumping in air at the rate of 70,000 cubic feet (1981 cubic metres) an hour using two compressors. This was done with great care as the last thing that Iron wanted was for the ship to right herself. If that had happened, any openings that had previously been blocked by the seabed would be exposed allowing the air to escape. If this happened the Glatton would sink back down again and the work would have to start all over again. The experiment worked but in order to prevent the Glatton from righting herself, two pairs of nine-inch wires were placed round the barbettes of the guns and passed under the starboard gunwale.

Four lifting lighters with a capacity of 1,000 tons were hired from the Admiralty at Portsmouth harbour. They arrived at the end of September 1925 and once positioned were, at low tide, ‘pinned down’ to the Glatton with wire hawsers. The weather, over the following weeks precluded any attempts to lift the Glatton but she had sufficient buoyancy that she was in danger of moving by herself and to avoid this, air was periodically let out.

On 2 December, the weather had settled and air was pumped into the Glatton. The lifting lighters were dewatered and with the Dapper, Lady Brassey and the other DHB tug Lady Duncannon, attached to the wreck. ‘It was the moment of truth’, to quote Captain Iron. ‘… As the tide began to rise, we waited to see what would happen. It was an anxious moment, and perhaps for the first time since I had had anything to do with this ‘major operation’ I began to wonder if after all I hadn’t bitten off more than I could chew.’ Suddenly a cheer broke out, the Glatton was rising! Slowly she rose, bottom up, and Captain Iron ordered that the operations be suspended for the day.

During the night and early the following morning, a flotilla of craft of all sizes arrived in Dover harbour. The trains from London were packed with would be spectators and reporters. By 8.30hrs, the Seafront was crowded with sightseers. Initially, little happened and a diver found that a cable was fouling and was dealt with by a small explosive charge. This sent up a jet of water much to the delight of the crowds and the boats that were beginning to crowd round, back off. It was a neap tide and once it turned at 10.30hrs slowly, the Glatton started to move. She was towed towards the eastern Dockyard until the tide began to ebb. That night, when the tide was right, she was moved out of the fairway and work was suspended.

It was on the spring tide of 19 and 20 February 1926 that the Glatton was moved to within 300-feet of the western pier of the Camber in the Eastern dockyard. The operation was undertaken over two spring tides and completed on 10 March when she was finally placed alongside the Camber pier. The whole operation had cost £12,000.

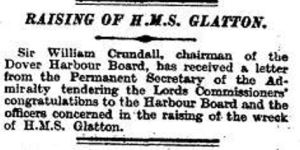

Congratulations on the lifting of the Glatton from the Permanent Secretary of the Admiralty. Times 08.04.1926

The Glatton was still upside down and the plates were taken off from her bottom. This was to allow the bodies to be removed and the shells unloaded. The bell of the Glatton was removed, cleaned, mounted and can be seen in the foyer of Harbour House today. A service was conducted on the upturned hull.

The Chairman of DHB, Sir William Crundall, received a letter of congratulations from the Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty that he passed on to Captain Iron along with Mr Polland and Mr. P. G. Sutton, who had assisted him. Captain Iron’s quotes above were taken from his book: Keeper of the Gate published by Sampson Low, Marston & Co 1936.

Messrs A O Hill Ltd, based alongside the Camber, subsequently broke up the vessel and this was completed by 1930. In May 1934, at the Court of Appeal Justices Slesser and Romer concurring dismissed an appeal by the Inland Revenue against a decision by Justice Finlay. This had enabled DHB to deduct from their assessed profits the cost of removing the wreck of the Glatton.

At the time that the Glatton was lifted, she was the second largest ship to be salved by the means of compressed air. She was also the only ship to be salved and carried inshore a distance of about 1400 feet (427 metres) at an angle of 60º, with all her guns – two 9.2-inch and four 6-inch and equipment intact.

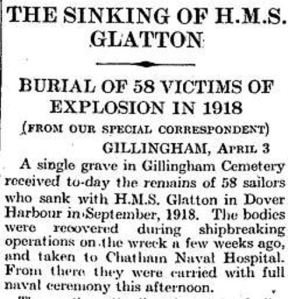

Memorial to the Glatton victims that had been in the vessel since 1918 buried at Gillingham. Times 04.04.1930

Sixty officers and men died in the original explosion on the Glatton and 19 more died of their injuries. The Market Hall was used as a mortuary and some of the men were buried in St James cemetery, Dover. Following the salvage, the bodies of a further 58 sailors were recovered from the Glatton and were taken to Chatham Naval Hospital. From there they were given a full naval ceremony at Gillingham cemetery on 3 April 1930.

- Presented: 11 February 2015