Admiralty Pier is one of the great British engineering feats of the 19th and early twentieth century. Since then it has played an important part in both national and local history. Part I of the story of the Admiralty Pier covers events leading up to and the almost completion of the Pier. Admiralty Pier Part II covers the building of Marine Station and the practical function of the Pier since.

The possibility of building Admiralty Pier, originally the western arm of the Harbour of Refuge had been through four enquiries by 1847 when the final approval was given. The first was in 1836, the second – a Royal Commission – in 1840, a Committee of the House of Commons in 1844, and Admiral Sir Bryan Martin’s Commission in 1845. The first Inquiry had been called at the behest of the Dover Harbour Commissioners, who wanted Dover to become a Harbour of Refuge for ships traversing the notoriously treacherous Strait of Dover.

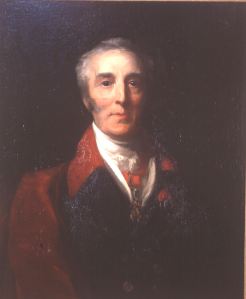

The other inquiries were direct descendents of the first with the added input from Arthur Wellesley, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) who had been installed as the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports in 1829. He was worried that if there were more hostilities with France, the port as it was, would be useless due to the Eastward Drift – shingle being washed into and blocking the harbour entrance. Wellington had appointed the famous civil engineer Thomas Telford (1757-1834) to find a way of tackling the problem. Although Telford was dead by the time his recommendations and other measures had been instigated, the result was the Wellington Dock, which was formerly opened by the Duke on 13 November 1846.

It was the combination of arguments put forward for a Harbour of Refuge and a National Naval Port on the south east coast that influenced Admiral Sir Bryan Martin’s Commission in 1845. They recommended that a harbour should be constructed in Dover Bay and the design submitted by James Walker (1781-1862), then the Dover harbour engineer, was accepted. His proposal covered an area of 520 acres and was estimated to cost £2,500,000. However, nothing happened, so there was another Inquiry asking why? Finally, approval was given in 1847, though for a different design.

The designed eventually chosen was drawn up by Sir John Hawkshaw (1811-1891) and was to be built under the supervision of Sir John Rennie (1794-1874). The main building contractor was Henry Lee & Sons of Chiswell Street, London. The construction process was divided into parts. The first started from the shore at Cheeseman’s Head – one of the bluffs on Archcliff promontory that was once part of the ancient harbour – and was 800-feet long extending almost at right angles. At the time, this was believed to be the most difficult part of the works and was estimated to cost £245,000.

The first phase began in November 1847, without any fanfare, when wooden staging was erected 100-feet long and 10-feet above high water level. It was not until Sunday 2 April 1848 that the formal laying of the foundation stone took place. The next day the seabed foundations were started. About three-feet of mud was first removed using a new dredging machine while at low tide men with shovels took over. Then the sea floor was flattened using a new-fangled steam operated machine. Blocks of Portland stone, each weighing about 3-tons, were brought by sea from William & John Freeman’s quarry at Grossland, Isle of Portland, Dorset. Dover Harbour Commissioners (DHB) charged Henry Lee & Sons 13½pence per ton to land these stone blocks!

The problem of placing the foundation stones was given to the young harbour engineer, Edward Druce (died 1898). A survey had shown that the harbour floor was solid and so the decision was whether the divers involved should be helmeted or whether diving bells were to be used. Druce opted for the latter. Each stone was lowered by crane and positioned by divers working in three large diving bells for 5-hours at a time. Eighteen blocks formed each horizontal course and were built to a height of 6-feet below the high water mark. The stones were then faced, on the west side, with granite, on the east side with Bramley Fall Stone. The Namurian sandstone, Bramley Fall Stone, was quarried at Horsforth in Leeds and was known for its strength and durability. The final height of the Pier was 10-feet above the high water mark and once the foundation level was laid the work was carried out by helmeted divers. An illustration of the time gives shows how this was undertaken.

In August 1849, when about 650-feet from the shore had been completed the Duke of Wellington paid one of his regular visits. As usual, he was escorted by James Walker, Henry Lee and harbour master – John Iron (I). The Duke was already aware that the seabed was a lot softer than had been anticipated such that the foundation stones had to be re-laid at a greater depth. Once that problem had been dealt with, Iron told the Duke that building work was having a calming effect on the sea on the eastward side and that it had curtailed the Eastward Drift. This had allowed the harbour entrance to be deepened by 3-feet for which the steam-dredging machine was used. However, Iron added, there was evidence that as the Pier progressed it was giving rise to flooding in the town. Wellington ensured that money was available to build a protective seawall from the base of the new Pier along the seafront to the Boundary Groyne opposite Guilford Battery – where the Harbour Commissioners jurisdiction ended.

All was going well until Tuesday 8 October 1850, when during an intense storm, centring on Dover, piles, 18-inches square were snapped and three 5-ton diving bells were carried out to sea – two being found later. At daybreak, the bay was strewn with fragments of timber and machinery including broken cranes, air pumps and traversers. The Duke of Wellington rode from Walmer to inspect the damage and accompanied by James Walker with Colonel Blanchard of the Ordnance went to the extreme end of what remained of the Pier. Remedial work was quickly undertaken and work on building the Pier resumed after two weeks only to be disrupted by another storm on 23 October and a far worse one on 15 December. In January 1851, another storm washed 200 stones out of position and they had to be re-laid.

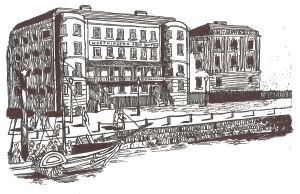

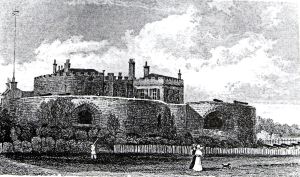

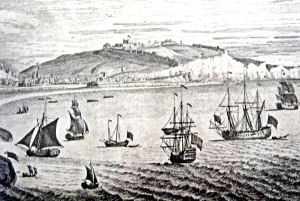

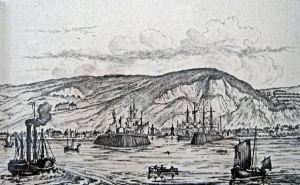

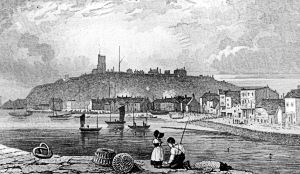

Dover Harbour c1850 from Western Heights. In the foreground is Wellington Dock, what was then the Bason now Granville Dock and the Tidal basin. The uppermost structure is the start of Admiralty Pier. Dover Library

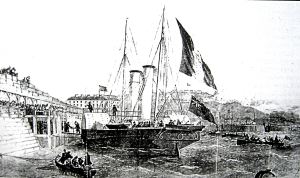

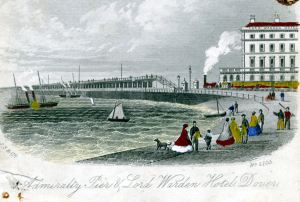

By 14 June 1851, the Pier was taking shape and on that day, the pleasure steamer, Father Thames, landed 50 passengers. Five days later, on 19 June 1851, it was announced that the first part of the Admiralty Pier was complete and the Princess Alice, became the first cross-Channel packet ship to use it. Elsewhere, it is wrongly stated that the packet Onyx landed passengers on 15 January 1851 – that day the Onyx was moored in the Downs due to bad weather. With the proximity of both the South Eastern Railway Company’s (SER) Town Station, opened in 1843, and the Lord Warden Hotel, it was hoped that the future use of the Pier for the purpose of landing and loading would be guaranteed.

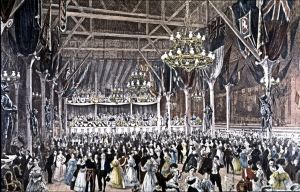

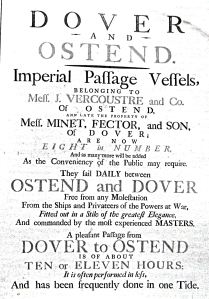

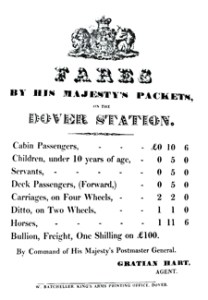

SER built a new Custom House near the Pier with the intention of using Admiralty Pier, but as the company was not allowed to run trains on the Pier to meet their ships the company moved all their vessels back to their own harbour at Folkestone. Albeit, the Pier was well used by the six Admiralty Packets steamers that carried mail from 1837 to 1854 and plied the Channel twice daily between Dover and the three ports of Calais, Boulogne and Ostend. Alongside the English mail steamers there were also French and Belgium mail packets and in 1851 the Great Exhibition in London ensured the Pier’s success. During the period of the Exhibition, passenger traffic from the Continent using the Packets was sometimes in excess of 200 passengers per ship.

As the Admiralty Pier gained in length, the problem of flooding, although alleviated by the new seawall, did not go away. This was used by SER and their supporters as an argument for the Harbour of Refuge to be sited in the Folkestone-Hythe Bay. On 27 August 1853 Sir James Graham (1792-1861), First Lord of the Admiralty, headed a retinue of delegates to Dover on an official visit. They were brought to Dover by Captain Luke Smithett, on the Vivid mail packet. The ship tied up on Admiralty Pier and the influential officials were met by Mayor Charles Lamb and the two Dover members of Parliament, Edward Rice (1790-1878) MP for Dover 1837-1857 and Henry Cadogan – later Viscount Chelsea (1812-1873) MP for Dover 1852-1857. The Admiralty representatives also inspected Archcliffe Fort where the Royal Artillery had recently fixed large guns to protect the envisaged Harbour of Refuge. The visit was successful and a subsequent Royal Commission recommended that the Admiralty Pier should be extended and that a gun turret should be incorporated.

At the time, the Bill for the Canterbury-Dover railway line was going through Parliament and eventually led to the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR). The company proposed to make Dover their main crossing point to the Continent in competition with the Folkestone based SER. In their evidence to the House of Lords on the Bill, SER stated that they had wanted to run their line along the Admiralty Pier but permission had been withheld. In their evidence, LCDR stated that they too wished to run their line along the Pier although their main station was in Elizabeth Street. Permission from the Admiralty was not forthcoming for either company.

On 27 December 1853, as the first phase of the Admiralty Pier was almost completed the foreman carpenter, Richard Mopat, was blown off the Pier during a gale and drowned. It was suggested an iron railing should be erected to stop such accidents happening again. A few weeks later the second phase, the building of a further 1,000-feet was began. However, to save money, instead of a solid wall of Portland stone, blocks were used to build the inner and outer walls. The trough between was filled with concrete blocks and rubble and finished with concrete. The concrete blocks were made on the adjacent Western (now Shakespeare) beach and the aim was to complete the second phase by November 1864.

Although this method of construction was cheaper, there were loud complaints regarding the slow rate of progress that was being made. This was mainly due to Treasury financial constraints and problems with the soft seabed that required sinking foundation stones much deeper than anticipated. In the House of Commons, when it was reported that thus far the Pier had cost £278,000. there was an outcry that the project was a waste of public money and funding should cease. In 1858, a House of Commons Select Committee was set up to look into this and they also listened to the argument over the need for a Harbour of Refuge. The Committee concluded that as long as the costs of the second phase did not exceed the financial amount lost through shipping disasters then the investment was worthwhile. However, instead of an eastern pier Dover would have to make do with a landing stage.

In 1859, the Admiralty finally agreed for SER to run onto the new Admiralty Pier for which SER agreed to contribute £3,000. They were told that there would be special facilities for packet ships. Five years previously in 1854, tenders had been invited for the prestigious and lucrative Packet contract and SER had expected to win it. Instead, it was awarded to Jenkins & Churchward though it was due for renewal in 1863.

SER planned that the new railway line would continue from Town Station on a curve onto the new Pier, so that passengers and mail would be adjacent to where the ships berthed. In order to do this it was necessary to build a substantial tall seawall between the west side of the Pier and the shore. This, SER shareholders agreed to pay for, as it also would have the added advantage of protecting the Lord Warden Hotel from strong southwesterly winds. At the time, there was a walkway from the Hotel to the railway station. The wall and the laying of the line was completed in the summer of 1861 and in October SER started running trains on the Admiralty Pier to meet the company’s passage service.

In 1861, the Harbours and Passing Tolls Act came into force with the aim of facilitating the Construction and Improvement of Harbours by authorising Loans to Harbour authorities. The Act abolished Dover’s Passing Tolls and embodied within it a new constitution that led to the Harbour Act of the same year. This Act abolished the Harbour Commissioners replacing them with the Dover Harbour Board (DHB) presided over by the Lord Warden (1866-1891) who, at the time, was George Leveson Gower the Earl Granville (1815-1891). The new Board consisted of six, two of which were members of Dover Corporation, two represented the railway companies, one the Admiralty and one the Board of Trade.

James Walker had ceased to be the harbour engineer but his company held the contract as consultant engineers until Walker’s death on 8 October 1862. Then all of the firm’s government contracts were passed to Messrs McClean and Stileman of Great George Street, London. They took up the Admiralty Pier contract in the spring of 1864. John Robinson McClean (1813-1873) was the President of the Institution of Civil Engineers for the years 1864 and 1865, and eminent engineer Francis Croughton Stileman (1824-1889) had been his partner since 1849. Edward Druce continued as the resident engineer and Henry Lee as the contractor for Admiralty Pier.

By 1863, 1,675-feet of the Admiralty Pier had been constructed and the length of the quay was 1,539-feet. For the third and final works, the costs had been estimated at £101,000 spread over two years. It was estimated that work would finish in November 1864 but government money was tight and opposition was growing. In November 1861, the London Chatham Dover Railway (LCDR) opened to Harbour Station. They successfully petitioned Parliament to run their trains along Admiralty Pier and they were charged the same as SER were being charged.

This appeared advantageous to SER, for to make way for their track in 1844, the pilot station was demolished on Cheeseman’s Head. In its place, a highly ornate pilot station was built of stone and standing on a bed of concrete 10 feet thick opening in 1848. This new tower was between the LCDR’s harbour station and the Admiralty Pier! Instead of building a parapet over the sea to circumvent the tower, LCDR noted that the ground floor of the tower had a ceiling height of 20ft (over 6 metres). They bid for the area to be gutted and laid their line through the Tower! Then, in 1863, LCDR won the converted Dover Mail Packet contract and from 30 August 1864, their trains ran through the Pilots tower to Admiralty Pier!

To add insult to injury, according to SER, the rules for the use of the Admiralty Pier were skewed in favour of LCDR. There was just room for two lines on the Pier with a central crossover that enabled trains to reach the further part of the single platform from the town end. The single platform was against the western parapet and during inclement weather waves broke over the parapet soaking passengers and their luggage! Initially, SER were pleased as they were designated the use of the platform at northern end of the Pier – nearest the town – and the LCDR the southern part. On the eastern side of the Pier were five landing berths, three inner and two outer. Berths one to three were for Continental steamers while the outer two were for Navy use. Berth 2 was designated strictly for the sole use of Packets and mail trains had priority. Near berth one, SER’s berth, was Mole Head Rock. Although this was a known shipping hazard, no attempt was made to remove it (see Ville de Liege story).

Map dated 1919 of Admiralty Pier showing the railway lines layout prior to the building of the extension landing stage and Marine Station started in 1909

Besides mail trains having priority, trains were not allowed onto the Pier before their advertised time and if an SER train was running late, it had to wait until the Pier was clear of LCDR trains. If trains from both companies arrived late, the mail train had priority and then the first to arrive was given access. If the second train was an LCDR and there were no mail trains, that was allowed access but if it was an SER train, it had to wait until the LCDR had left! Finally, if both companies had trains on the Pier the SER train had to leave before the LCDR . The rules quickly became abhorrent to SER who complained bitterly but to no avail and they withdrew their passage service from Dover. On that first day that Admiralty Pier was open to LCDR trains, 30 August 1864, the Duke and Princess Mary of Cambridge arrived on Admiralty Pier where the Royal entourage embarked on the LCDR steamer Wave for France. LCDR used the event for publicity purposes, saying that Royalty had opened their Admiralty Pier line!

Admiralty Pier c1890 with a Sterling engine on the line. Note shutters on signal box. Bob Hollingsbee collection, Dover Museum

At the time the Admiralty Pier station did not have a covering, but one was quickly erected for the Royals. This was later temporarily reinforced several times but remained for years after. Indeed, one of the many complaints dated 1879 said, ‘it is bad enough to stand shivering on a wet, stormy day in a seasick crowd waiting to land. But to land across a mere plank in motion, at an angle of 45º on to a slippery pier, to pass up soaked staircases along open planks and to walk some 200 yards drenched by the rain and frozen by the wind … No rank, wealth or infirmity can buy off the dread and the danger of that wretched five minutes in which hundreds of people, worn out with travelling, tired and weak, are drenched and chilled as a preparation for their long journey back to London.’ Of interest, the signal box at the northern end of the Admiralty Pier lines had storm shutters to protect the windows during rough weather.

On 25 June 1865, the Admiralty Pier upper promenade opened and both promenades were 250 yards in length. The station and the lines were on the lower level at the east side of Pier adjacent to the landing berths. Both promenades were laid with flagstones weighing a ton and a half each and walkways were lit by gas ornamental lamps. The lower one also had telegraph posts carrying two sets of wires, one for SER use and the other for LCDR going to the two sets of offices. The offices were on the landward side of the northern end of the platform. Both promenades were expected to become major tourist attractions and the council drew up a list of charges and employed gatekeepers to collect the revenue. However, restrictions were imposed by the Admiralty forbidding the public access to the lower Pier twenty minutes prior to the arrival of a train or a cross-Channel ship until its departure and ten minutes prior to the same for the Upper Pier.

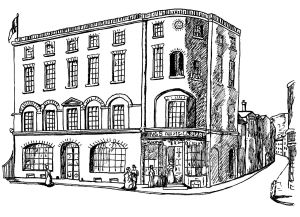

Admiralty Pier with a London, Chatham and Dover Railway Company train and packet ship in the Bay. South Eastern Railway Lord Warden is on the right. Dover Museum

During the summer of 1865 and 1866, the restrictions meant that the Pier was closed to visitors for most of the time. This naturally caused a public outcry. Edward Knocker, Dover Town Clerk wrote a terse letter to the Admiralty but they were resolute that as the railway companies paid rent, apart from the Royal Navy, they had sole use. Others, including the Corporation could only use the Pier at the Navy’s or railway companies’ convenience. Matters came to a head when an excursion boat from Ramsgate was not allowed to dock against the Pier to disembark and embark its 100+ passengers that were visiting Dover. The passengers had to stand on the open quayside for some three hours during which time there was a rainstorm. Although nothing was done to ameliorate such situations, to placate the council, iron railings were erected along the eastern edge of the upper promenade so that it could be opened to the public.

As there was no chance of the eastern pier ever being built and the ships were increasing in size, it became imperative to deepen the Bason, Wellington Dock and the Tidal Basin to retain practical use. These measures were costed at £166,000 and the Parliamentary Dover Harbour Improvement Bill was submitted by DHB even though the scheme did not have the backing of the Admiralty. However, the responsibility for the building of Admiralty Pier had been passed to the Board of Trade and in March 1867, the final part of the Pier began. The consulting engineers were again McClean and Stileman.

By this time, the jetties were completed with the inner jetties having a depth of 10 to 17 feet and the outer 40 feet at low water spring tide. However, they were all vulnerable to southwesterly winds and the resulting cross-currents. Although the argument for the eastern pier was put forward, it was rejected. Instead, it was agreed that the final part of the Admiralty Pier would be changed. The plans were drawn up for it to built in a curve, 600-feet long with a substantial round pier head. The cost was estimated at £200,000 and therefore rejected. Another plan was submitted and after much deliberation was agreed. The final part was to be 300-feet in length on an easterly curve ending with a not so substantial square cornered head.

Wreck of the Ferret at the Volunteer Review of Easter 1869. Illustrated London News 10.04.1869. Dover Lbrary

On 29 March 1869 – the Easter weekend – during a severe storm the sail-training brig, Ferret, which had been on a mooring buoy, broke free, hit the Admiralty Pier and eventually sank. On board were 17 men, 8 stewards and 86 boys under training – some of which belonged to Dover Sea Scouts (Now Sea Cadets). All the crew and the boys were rescued but at the subsequent inquiry, the lack of the second pier of the proposed Harbour of Refuge was given as a reason for the mishap. Nonetheless, later that year, to save money, the services of McClean and Stileman were dispensed with and Edward Druce was promoted as overall engineer in charge and took over from Henry Lee as builder at the end of 1869.

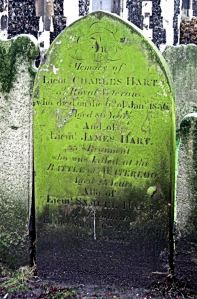

Ten years before, in 1859, military engineer, Major William Francis Drummond Jervois, (1821-1897) – later knighted – was Secretary to a Royal Commission set up to examine the efficiency of the country’s land based fortifications against naval attack. His report suggested that a gun turret should be erected on Admiralty Pier head. Work started on building the Turret in September 1871 with Henry Lee winning the building contract for the £20,000 superstructure. Within two years, the Admiralty had altered the original design to that of an iron-plated circular rotating structure weighing over 700 tons. It was mounted with two 80-ton, 16-inch rifled muzzle-loaders with a range of up to 4.3 miles.

On 24 July 1871, the Dover Harbour Improvement Bill received Royal Assent and work started on deepening Bason so those vessels drawing 21-feet could enter at high water. The Bason was completed on 6 July 1874, opened by the Lord Warden, Earl Granville and was renamed Granville Dock. On 30 October 1871, the Belgium Government’s packet ship, the Leopold, became the first ship carrying mail from Australia and India that docked alongside Admiralty Pier. There was also a regular boat service between London and Dover by the General Steam Navigation Company of Great Tower Street, London.

The Admiralty Pier, finally completed on 31 March 1875, was 2,100-feet long and cost £693,077. However, if the wind was from the south, southeast or southwest, the Pier did not offer a leeward side and there was the danger from the Mole rocks. In the year the Admiralty Pier was completed five vessels were shipwrecked on the Mole rocks, with one, a timber ship losing all hands. By 1881, such accidents were commonplace and the Board of Trade, in an effort to find a solution laid down two sets of moorings consisting of 200-feet of chain, off the eastward side of the Pier.

Further, the square cornered head of Admiralty Pier had been giving concern but it was assumed that the lighthouse would stop any serious accidents. However, before it was completed, at 23.00hrs on 28 March 1873, during thick fog, the large screw steamer International belonging to the International Telegraph Company on her way from London to Bilboa, Spain, ran into one of the corners of the Pier. The ship knocked away staging, two large piles, displaced some of the enormous blocks of stone and became entangled in chains and piling. Shortly after the Turret was finished, the Admiralty Pier head was extended and widened slightly getting rid of the square corners.

The third concern was the Pier’s vulnerability in bad weather. This was apparent on 1 January 1877 when the upper part of the centre of the curve and the parapet on the western side were swept away and the upper galleries destroyed in a storm. The Admiralty estimated that the cost of the damage to be £26,000 and sought the advice of the Pier’s designer, Sir John Hawkshaw. However, his new design was rejected as too expensive and other options were sought. In the end, the project devolved down to Druce, who stuck to Hawkshaw’s new design and brought in local builder William Adcock to carry out the work. Adcock was rarely the cheapest to tender for work but he did have the reputation as a builder of excellence. A solid parapet was built with a vertical face and a wider base, the thinnest part was 12-feet wide and the stone facing being filled with concrete.

On 19 January 1881, the Pier again suffered damage. The large flagstones, weighing about a ton and a half each, forming the 250 yard promenade were lifted, displaced and in some places the solid concrete base on which the promenade was laid, was lifted out. Lampposts were bent and two were snapped off, telegraph posts were flattened and some of the iron railings were swept away. The windows of the offices were blown out, the doors wrenched off their hinges and the buildings on the wharf flattened. The repairs carried out in 1877 to the upper promenade, however, held. The damage was estimated at £10,000 and Adcock was again called in to carry out repairs.

Some 200-300 people gathered on and around the Turret on Tuesday 24 August 1875 to see Captain Matthew Webb (1848-1883) dive off at the start of the first successful swim across the English Channel to France. The time taken was 21 hours 45 minutes and he had actually swum 39 miles (64 kilometres). The Webb memorial can be seen in the Gateway Gardens on Marine Parade.

On 21 January 1885, men in steam launches from the Royal Navy gunboat Triton, under the supervision of Captain Tizard, started taking soundings for what was locally believed to be a national harbour for the Navy. It was said that the proposed harbour would be 700 acres of water surrounded by three arms. The eastern arm would be from below the Langdon barracks on the eastern cliffs and the same length as the Admiralty Pier, which would be the western arm. In between there would be a breakwater giving an east and west entrance to the proposed harbour. Later, an official notification stated that the purpose of the survey was to see if there had been any shoaling due to the erection of the Admiralty Pier. This was followed by another statement saying that the survey had been undertaken for the purpose of the proposed Harbour of Refuge.

In 1888 the Wellington Dock gates were widened ten feet to accommodate the new cross-Channel ships such as the 1,030 gross tonnage steel paddle steamer Victoria that came on station in 1886 and the 1,213 gross tonnage steel paddle steamer Empress that arrived in 1887 as well as colliers. New coal stores for the convenience of local coal-merchants were built on the Northampton Quay. The slipway was lengthened, strengthened and widened to take vessels up to 800 tons. However, the LCDR representative on DHB was far from happy. The company, he argued made a considerable contribution to DHB’s revenues to provide accommodation of their fleet and the Continental fleets including French and Ostend mail boats and steamers. However, due to the lack of space, they were compelled to keep their large and valuable boats under steam all night in the Downs or in the Bay, causing the company unnecessary expense and the crew and passengers great discomfort.

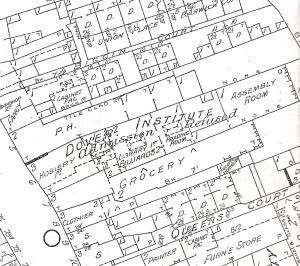

1890 Map showing the proximity of the SER Town Station to Admiralty Pier and the landing stages. The LCDR Harbour Station is situated off the top of this map.

Further, during southeasterly gales, it was exceedingly difficult to land passengers and occasionally incoming packets had to lie outside the harbour tossing on a rough sea for several hours as it was dangerous, if not impossible, for any vessels to go alongside. Other members of the Board, excepting the SER representative, added to this saying that as the port did not have deep water at all states of the tide it was virtually closed to commerce of the world. That even as a Harbour of Refuge, the harbour was grossly inadequate. Dover Corporation and most of the townsfolk were of the same opinion.

On 3 October 1890, DHB, under the chairmanship of the deputy chairman Layton Lowdes as Lord Granville was indisposed due to gout, voted to undertake the development of the much-needed Harbour of Refuge/Commercial harbour themselves. They unanimously agreed to apply in the next session of Parliament for a Bill to authorise DHB to spend £300,000. In addition, to raise more money they asked for the introduction of a passenger tax similar to that imposed by the French government to finance their harbours in northern France. The Register, James Stilwell, drafted the application and included plans for the new harbour submitted by Sir John Coode (1816-1892), of Coode, Son and Matthews.

The proposed harbour was to be bound on the western side by the Admiralty Pier extended 560-feet. On the eastern side, an arm 2,760-feet seaward starting in a southerly direction and curving towards the southwest. This would give an entrance 450-feet wide facing towards the east and sheltered by an overlap of the extended Admiralty Pier. Within the new harbour would be a water station – a covered space to accommodate four or five cross Channel steamers and a connection from the shore next to which railway lines would be laid and connected to the main lines. However, the best contract price for the proposed eastern arm was over £400,000. Therefore, in the final submission presented in August 1892, the estimate for the work was increased to £600,000.

In the meantime the problems of the existing situation continued. On 1 February 1892, the Belgium government’s packet ship the Prince Baudouin was going alongside the Pier during a heavy gale, to disembark passengers. The tide and a heavy swell caused by a strong southwesterly wind caught her and she hit the Pier with great force sustaining considerable damage on the starboard side. The ship immediately started to take in water. The captain ran for what was the harbour entrance at that time but she struck the Mole Rocks. There she sank close to where another ship, a German steamer, Liebenstein, had sank a few weeks before. The passengers, crew and mails were rescued and temporary repairs were made to the Prince Baudouin following which she was refloated and taken into the old harbour.

A month later the Belgium government’s packet ship Ville de Douvres, carrying mails and passengers, while trying to get alongside the Admiralty Pier during a gale touched the Mole Rocks. The LCDR mail packet Foam successfully towed her off. The following month, the LCDR steamer Prince hit the Mole rocks while trying to berth alongside the Pier during rough weather. These accidents were by no means out of the ordinary but served to show the seriousness of the problems.

The Bill for a Harbour of Refuge/Commercial Harbour was passed by Parliament who also granted the power for DHB to levy a tax of 1 shilling (5pence) on each Channel passenger. Parliament also agreed to lease the Admiralty Pier to DHB for 99-years and the arrangements were drawn up and signed by the end of 1891. Shortly afterwards Edward Druce retired as resident engineer but before work could begin on either the Admiralty or eastern pier the proposals had to be sanctioned by the Board of Admiralty. On 20 July 1893, the first stone of the eastern arm of the project was laid by Prince of Wales, (later Edward VII, 1901-1910) and took the name of Prince of Wales Pier. In September 1894, the first submarine block of the Prince of Wales Pier was laid on the bed of the sea but approval, from the Admiralty, still had not been given for the proposed alterations to the Admiralty Pier.

At this time, the Admiralty was taking a close interest in events on mainland Europe. On 18 January 1871, Germany had unified under the country’s first Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), which changed the balance of power in Europe. Bismarck had strived to keep the peace but in 1890, Wilhelm II (1888-1918) effectively sacked him and then pursued a massive naval expansion. This galvanised the British government to consider the construction of a National Harbour on the south coast. In May 1895, when about three-quarters of the Prince of Wales Pier had been built, the Admiralty announced its decision – it was going to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy.

For the new Admiralty Harbour, Coode, Son & Matthew were appointed as design engineers with Major Sir Henry Pilkington (1849-1930) engineer in charge. It was not until 9 November 1897 that the building contractors were announced – Messrs S Pearson & Son Ltd. The extension of Admiralty Pier was to be completed in 8 years and the remainder of the harbour in 10 years. Subcontractors included two local firms, one headed by William Adcock and the other Richard Barwick. The proposed new Harbour consisted of:

i. At the west, Admiralty Pier extended by 2,000-feet in an easterly direction

ii. The erection of an Eastern Arm, 3,320-feet long from the east cliff at Langdon Hole in a southerly direction from a 3,850-foot long sea wall reclaiming an area of over twenty acres.

iii. A Southern Breakwater, 4,300-feet long, three-quarters of a mile from the shore.

iv. This was separated from the Admiralty Pier extension by a western entrance 800-foot wide and the eastern arm by the eastern entrance 600-feet wide. At the lowest tide, the depth of water in the entrances was to be 42-feet.

It was designed to moor twenty battleships plus a considerable number of smaller naval craft and the finance was provided under various Naval Works Acts. The first Naval Works Act was passed in 1895 when it was estimated that the cost would be £3,500,000. The proposal made it necessary to alter the plans for commercial harbour including the Prince of Wales Pier. Although completed in 1902 with a curve at the seaward end, this was to be demolished making the Pier straight.

Before their work began, Pearson’s bought a quarry in Cornwall containing all the necessary granite for the proposed works. This was to be used to face massive concrete blocks that would form the main structure of the new harbour walls. Skilled men in many different crafts were recruited, boarding huts, offices, foundries, workshops, repair shops and stores were erected and in the summer of 1898 work commenced. Huon Pine was brought from the former penal colony of Dover, Tasmania, (see Transportation story), by ship to provide temporary staging around which the new harbour was built.

Although there was fear, in many quarters of possible German hostility, others believed this to be unfounded. In August 1898, nearly 2,000 carrier pigeons arrived from Germany via Ostend on the Belgium mail packet, Princess Josephine to be trained for German military purposes to fly back to a base in Dusseldoff, Cologne. A fee was paid to DHB and the birds were released from Admiralty Pier but instead of flying back across the Channel they stayed in England roosting on both the Admiralty Pier and the Western Heights! This led to a public outcry, particularly as they were German military pigeons. The following year another 600 birds were brought to England and DHB were assured that they came from Belgium. The weather was clear and at lower levels there was hardly any wind but at higher levels an easterly was blowing. On reaching the high wind, the birds attempted to face it but then chose a more southerly course. It was reported that none reached their chosen destination in Belgium.

The concrete blocks for the new harbour were made on two sites – one at the east end of the bay (see the Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Mill Railway Line story part I). The second, for the Admiralty Pier, was on what is now Shakespeare beach but then called the Western beach. The block-making yard on Shakespeare beach was started in the summer of 1898 after a low seawall was constructed. By March 1899, the block-making floor, concrete mixers and cement sheds were practically complete, a work yard a goliath had almost been erected and block making was started. Blocks weighed between 24 and 42-tons, were made out of cement, sand and shingle, the latter brought from Rye by train.

Block making c1900. Concrete poured into wood moulds that opened at the side when set. Dover Harbour Board

The concrete was made in large mixers and some 250 blocks were made at any one time. Each mould had a circular convex protrusion at each side that formed a semi-circular indentation in the blocks when placed on the seabed next to each other, forming a cylindrical cavity. Called ‘joggling’, when the blocks were laid, the cavity would be filled with concrete to bind the blocks together. Each block was ‘cored,’ to enable easy lifting, with two slanting holes created by two large pieces of wood in the mould. After two days the moulds were slackened off and the wood creating the cores were removed. Later Lewis bars – iron bolts with a ‘T’ head at the lower end – were inserted and given a quarter turn and shackles were attached to the upper ends to enable the cranes to lift the blocks. After a further eight days, depending on the weather, the moulds were removed and the blocks carried by goliaths – cranes with a span of 100-feet that could lift 50-tons – to the Admiralty Pier side of the beach. There they were weighted, dated, numbered and then placed in stacks for at least six weeks until sufficiently cured for use.

Diving bell with the men who worked inside to prepare the sea bed being lowered into the sea by a crane . Dover Transport Museum

For the foundations of the new harbour walls, the upper crust of the seabed was removed by great clamshell grabs until the solid seabed was reached. Siebe Gorman & Company Ltd undertook the underwater work, with divers working in diving bells to level the prepared surface of the seabed. The diving bells, of which there were seven, weighed about 40-tons, 17-feet long and 10-feet wide, and were swung and then lowered into the sea by a crane. There were about 80 divers working on the project with each diving bell with space for up to six men. On reaching the seabed, it was usual for some water to have leaked into the bell, often about 2-feet. This was driven out by compressed air. Each bell was lit by electricity with the lights being placed close to the thick glass windows. It was usual for four men to work in the bells under an air pressure of 27lbs per square inch (this being sufficient to maintain the bell ‘dry’ in water depth up to 60-feet) for three hours. They dug up the seabed using mechanical shovels until it was smooth and level. The material excavated was put into a large box and taken to the surface. Throughout operations, the divers were in contact with the crane driver by mechanical means. Helping the divers were men working from open rowing boats.

Huon pine staging posts across which a lattice of steel girders were bolted and on these, heavy timber platforms were laid.

Huon pine staging posts, measuring some 100-feet from top to bottom and 20-inches square, were floated into position between empty barrels. Two sets of six iron-shod posts were driven into the seabed every 50-feet opposite one another by pile drivers. Across these posts a lattice of steel girders were bolted and on these, heavy timber platforms some 15-feet wide, crane/railway lines were laid. The platforms were approximately 28-feet above the high water mark. Gradually the staging was built out to sea from both the Admiralty Pier and on the eastern side, what was to be the Eastern arm of the new Admiralty Harbour.

Between the piers, the concrete blocks were laid by a 60-ton goliath crane lowering the blocks into the sea. Divers not working from within bells then put these into place. To prevent lateral movement caused by storm waves the blocks were ‘joggled’ by the divers filling the cylindrical cavities with concrete in bags that consolidated the mass into a solid structure. The blocks that formed the ends of the Arms and the Breakwater were bound together with iron bars.

The bottom of the new harbour walls were 36-feet wide decreasing to 30-feet wide at the top and was perpendicular on the harbour side and stepped on the seaward side. As the concrete walls were completed, the cement blocks above the low water mark were bedded and grouted with cement and faced with granite blocks between one and five tons each. In total for the whole harbour, over 3½million tons of granite was used, 1,920,000 tons of concrete blocks – about 64,000 blocks and 1,500,000 cubic feet of timber.

By October 1898, due to the ongoing construction of the Prince of Wales Pier, the area between that Pier and Admiralty Pier was increasingly subject to a heavy swell that, at times, made it impossible to berth alongside Admiralty Pier. During such conditions, ships were diverted to Folkestone. A meeting was convened in November 1898 between the DHB, the SER, LDCR and the Continental railway companies whose ships used Dover harbour and the Admiralty, over this problem. The Admiralty said that the contract for the Admiralty Pier extension was to be completed two years less than the remainder of the works but they would give these works even higher priority.

Widening of the Admiralty Pier around the Turret, the old lighthouse on top of the Turret is on the right and the new temporary tall one is on the left. Nick Catford

The old small lighthouse close to the Turret that had been moved to the roof was replaced and much later was demolished. Initially a taller temporary steel lighthouse, 76-feet high came on station in August 1899, while another lighthouse was mounted on top of the most seaward of the cranes and was moved forward as construction of the Pier extension progressed. To supplement these the Admiralty brought in a lightship that was moored at the end of the works and fog signalling apparatus was installed. Lightships were also in place off the end of the Eastern Arm works and Southern Breakwater; however, they were all vulnerable to weather and collisions from other ships.

The first lightship off the Admiralty Pier foundered in a gale and the crew had to be rescued by the lifeboat. A larger lightship replaced it but was hit by an Atlantic liner. The next one was much larger but the French mail packet Le Nord hit her at 23.30 on 12 November 1901. On board the lightship were both the crew and the relief crew, 16, all of whom lost their lives. In the early hours of 10 May 1902, the 2,900-ton steamer Brator hit another lightship and the Dover lifeboat went to the rescue. The captain and three of the lightship’s crew, who were seriously injured, were transferred by the lifeboat to the Seaman’s Mission, where they were treated.

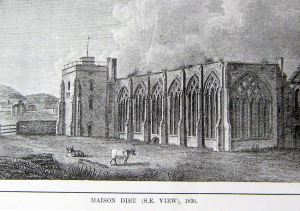

In November 1900, Dover Harbour Board presented a Bill to Parliament to complete and equip the Commercial harbour and make improvements to the old harbour. Part of the proposals was that of a jetty 1,000-foot long, starting from land reclaimed between South Pier and Admiralty Pier. Called a Water Station, the roofing was to extend from one pier to the other and it housed four berths. This would enable, according to the proposal, passengers to embark and disembark. It was also envisaged that nearby, adjacent to Admiralty Pier a large floating dock was to be erected.

Although land reclamation had already started, neither project came to anything. Within the Bill was a request, by the railway companies, asking for the right to lay crane lines along Admiralty pier in order improve the handling of passenger luggage. This was sanctioned and DHB engineer, Arthur Thomas Walmisley (1848-1923), designed two electric cranes for the purpose. These were built, installed and on 26 June 1903, with great pomp and surrounded by officials, one of the cranes was put to use. A top portion of a former South Eastern and Chatham Railway Company (SECR -a loose amalgamation of the former SER and LCDR) truck weighing approximately 15-hundredweight was lowered by one of the cranes into the hold of the Le Nord, on one side of the Admiralty Pier. The ship then steamed round to the other side where the second crane lifted out the truck and put it back onto its bogie section.

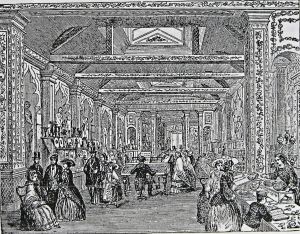

In the speech that followed by Sir William Crundall, the Deputy Chairman of DHB, he announced that these were the first electric cranes to be employed by a Harbour Board or Dock company in the country and were to be used for the transport of passenger baggage. By this time, there were two buffets for passengers awaiting departure of either a ship or a train on Admiralty Pier station provided by Gordon Hotels Ltd. Albeit, during rough weather, the buffets were closed and trains did not traverse the Pier. If passengers either embarked or disembark during such times, they were still forced to walk the length of the Pier often carrying or wheeling their luggage under inadequate, aged, shelter. This, the railway companies blamed on DHB as they had continually refused to pay for adequate cover for passengers.

Even before the Prince of Wales Pier was completed, DHB were considering constructing a berth on the Admiralty Pier side for Atlantic liners. Sir William Crundall, along with DHB Register, Worsfold Mowll, John Coode of the firm Messrs Coode, Son and Matthews, DHB engineer Arthur Walmisley and Harbour Master – John Iron (II), left for Germany to raise interest. On 3 September 1901, they met Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888-1918), who was wearing the uniform of a British Admiral, at Potsdam Palace. Present were the German Secretaries of State, Baron von Richtofen and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930), Herr Weigland and Albert Ballin (1857-1918), Director-Generals of Norddeutscher Lloyd line and the Hamburg-Amerika Steamship Companies respectively. The Kaiser had a billiard table prepared so that charts and relevant papers could be spread out when Sir William made a presentation. Afterwards the Dover deputation were entertained to a luncheon at the Palace and the following morning they left for The Hague for discussions with board members of the Dutch Atlantic Service.

On 15 December 1903, an agreement was signed between DHB, SECR and the Hamburg-Amerika Line for their ocean going cruise ships to call into Dover from 1 July 1904. The Atlantic liners berth was in what was designated as the Commercial harbour and an electric swing bridge was constructed to carry the railway over the Wellington Dock entrance to the Prince of Wales Pier. The Prinz Waldermar arrived in July 1904 berthing alongside a newly built transatlantic ships’ landing stage on the east side. The Continental passage ships had been were using the smaller jetty on the west side of the Pier but an Admiralty Order in Council was issued stating that the Admiralty harbour was only for the use by the Royal Navy vessels. Commercial traffic was only to moor in the Commercial harbour, to the west of the Prince of Wales Pier, contravention carried a £10 fine. Moorings for 13 battleships, 4 big cruisers and 10 smaller cruisers, as well as 36 torpedo craft, were laid in 1905.

During extremely heavy weather, work was suspended on the new Admiralty Harbour, sometimes for days at a time. A storm lasting several days in September 1903, swept away part of the Admiralty Pier extension staging and a huge cage that had been erected over the Southern Breakwater started to disintegrate. The cage was built out of Huon pine and steel girders on which goliath cranes stood. The building of the Southern breakwater was the most difficult because of its exposed position and the depth of water – at high spring tides some 45 to 55-feet. Work had started in August 1904 when the strongly built staging was erected in the same way as that of Admiralty Pier and the Eastern Arm. Most of the 80 divers were involved.

Because of the potential scouring and tidal action of the sea ‘aprons’ projecting 25-feet horizontally from the base were built on the seaward side of the Southern Breakwater. The beds for the aprons were excavated to a depth of 2-feet and were built using blocks weighing from 9-14tons and 3½-feet deep. These were laid using powerful cranes. On the seaward side of both the Admiralty Pier and the Eastern Arm, parapets were erected 11-feet and 10-feet wide respectively, the top of the Admiralty Pier being 43½-feet and Eastern Arm 39-feet above low water. Level with the bottom of the parapet was/is a ‘bull nose’ or blunt lip, bending outwards to the sea in order to try to deflect and to help combat sea washing over the harbour walls.

By January 1905, 1,600-feet of the Southern Breakwater was above the low water mark and the Admiralty Pier extension was almost completed. It was intended that the Admiralty Pier would overlap the Southern Breakwater by some 500-feet in order to allow vessels to enter safely. However, during the construction of the Breakwater, because of the staging, this was reduced to less than 400-feet resulting in ships’ sterns being in the strong tide while the bow was in the calmer water. This made the entrance into the harbour difficult and a Red Star Line vessel and a number of cross-Channel ferries had collided with staging.

In June 1906 the Prinz Joachim collided with the staging and the Admiralty reacted by issuing a directive saying that the harbour was unsafe for cruise vessels to enter and the entrance was to be redesigned to be 800-feet wide. A few weeks later, on 13 July 1906, the German liner Deutschland – the fastest liner in the World – hit the Southern Breakwater jetty with her stern. Then her bow hit the Prince of Wales Pier seriously damaging her stem and the plating on either side of her bow. Her voyage to America was abandoned.

An agreement was reached, that on completion of the Admiralty Pier, DHB was to be given the lease of the whole of the Pier in return for the Admiralty taking over the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier. This was confirmed by Act of Parliament in 1906. The same Act also provided for the widening of the old portion of the Admiralty Pier, bringing it, architecturally, into line with the extension and for the construction of a Continental marine station.

Because of the transatlantic liners disasters, the Admiralty, in 1907, undertook a number of tests to check out the safety of the harbour. Battleship Africa and cruiser Duke of Edinburgh both encountered problems on entering the Western entrance. It was also found that the mooring sites were unsuitable for such large vessels particularly in gusty winds. Smaller ships and submarines were subjected to pitching and rolling that was at the best uncomfortable for the crew or at worst brought about severe seasickness. The only way to reduce the incoming swell was to narrow the western entrance making it dangerous for ships to enter. The Admiralty therefore decided to build a tidal dock or camber adjacent to the Eastern Arm.

With the proposed widening of the Admiralty Pier, a further increase of 1 shilling on the passenger tax was required. This was to give the income necessary to meet the interest charges and sinking fund on a loan of £1m and under section 27 of the 1906 Dover Harbour (Works etc) Act it was agreed. The original levy was 1s6d (7½pence) on passengers landing and embarking, the 1906 levy was increased to 2s6d (12½pence). The interest on the £1m loan was agreed at 4% and the sinking fund 2½%. Worsfold Mowll, DHB Register, giving evidence to the House of Commons, said that over and above the individual passenger tax, 5shillings was received for every train that went onto the Admiralty Pier and £1 for every ship that went alongside.

Admiralty Pier during construction of extension. Two railway lines, boat builders, steamer berthed on the western side. Dover Library

In September 1907 the Southern Breakwater was completed and the Admiralty withdrew its danger notice to transatlantic liners. Then only two months later, the Red Star liner Finland struck the end of the Southern Breakwater. The accident caused some damage to the ship but more to the Breakwater. Shortly after the Germania hit the end of the Prince of Wales Pier. By that time, it had been agreed that Pearson’s would build an outer landing stage against Admiralty Pier for both cross-Channel ships and for transatlantic liners to avoid such accidents. Orders were also issued stating that until completion of the Admiralty Harbour a Union Jack was to be hoisted at the Coastguard signal station, on the Admiralty Pier when it was safe for ships to enter the harbour. When the flag was dipped, it was safer for ships to remain outside.

As the Admiralty Harbour works were reaching their completion the Lords of the Admiralty paid visits. On each occasion they were met by Sir William Crundall and members and officers of DHB along with Dover Mayor Walter Emden and Corporation. Early in 1908, the battleship Jupiter started a series of trials of the harbour entrances and the moorings. The rebuilding of the Admiralty Pier Turret was started in March and a second fort was built at the end of Admiralty Pier. Similar forts were built on the Southern Breakwater and at the end of the Eastern Arm. A new steel lighthouse was erected on the end of Admiralty Pier and was first used on 7 October 1908.

Admiralty Harbour final stone laid by George, Prince of Wales later George V (1910-1936) on 15 October 1909. LS 2010

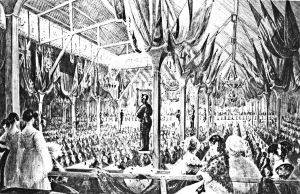

During a severe gale on Friday 15 October 1909, Admiral of the Fleet, George, Prince of Wales later George V (1910-1936) arrived in Dover by train and was driven to the shore end of the Eastern Arm where he laid the last stone commemorating the building of the Admiralty Harbour. Inside a cavity under the stone is a casket containing a parchment telling of the construction of the Admiralty Harbour, copies of the Times, Dover Express and the Dover Chronicle along with coins of the realm. Following the ceremony, the Prince was driven to the Clock Tower, on the seafront, where he boarded a train to the Admiralty Pier station. Alongside was the Royal Yacht Enchantress, which the Prince and the dignitaries boarded to enjoy a lunch.

Approximately, between 1,500 and 1,800 men worked on the project and many accidents and some deaths occurred. However, with regard to the divers, no deaths or serious injuries were recorded in connection with working either with compressed air or in diving bells. Part 2 of the Admiralty Pier continues the story from the official opening in 1909 to the present day.

Presented: 30 April 2015

Of Note:

Jur Kingma tells me that the Dover Admiralty Pier was the inspiration of the piers/breakwaters of the IJmuiden seaport on the Amsterdam Ship Canal. (1865-1876). The consultant engineer of the Amsterdam Ship Canal company was Sir John Hawkshaw and the Contractor was Henry Lee & Sons. Engineer Charles Burn, worked for the Amsterdam Water Supply Company and wrote a book on the building of Admiralty Pier and he with Bland W Croker made the first plans for the Amsterdam Ship Canal. In IJmuiden a large factory opened to make the concrete blocks for the Ship Canal and the first Titan crane – designed by Darnton Hutton, engineer of Henry Lee & Sons – was used in 1870 at IJmuiden.