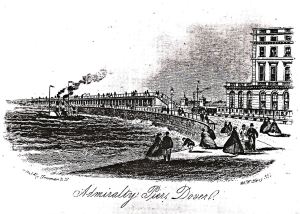

Admiralty Pier circa1900 showing the new extension. Dover Museum

Admiralty Pier is one of the major engineering feats of the late 19th – early twentieth century, and the story of its building was covered in Part I Admiralty Pier. Briefly, the first part of the Pier was started in November 1847 and finally completed on 31 March 1875. Parliament agreed to lease the Pier to Dover Harbour Board (DHB) for 99-years in 1891 and on 26 July 1893 the first stone, of the eastern arm of what DHB envisaged to be its Commercial Harbour, was laid by Prince of Wales, (later Edward VII, 1901-1910). This became the Prince of Wales Pier and was completed in January 1902. In May 1895, the Admiralty announced that it was going to use the port of Dover as a base for the Royal Navy and would build an Admiralty Harbour to enclose Dover Bay. Admiralty Pier was extended, the Eastern Arm and Southern Breakwater built and on 15 October 1909 George Prince of Wales, later George V (1910-1936), opened the Dover Admiralty Harbour.

Admiralty Pier railway line circa1907. Nick Catford

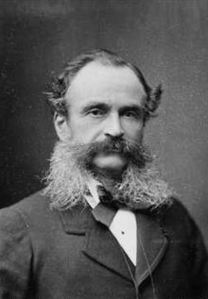

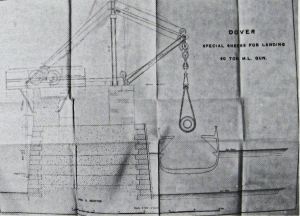

In 1907 it was agreed by DHB to surrender the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier for use by the Admiralty in order to widen the Admiralty Pier and build a Marine Station for the Continental packets ships and cruise liners. The Admiralty Pier extension had been completed by 7 October 1908 and at the head a steel lighthouse was constructed. This was from an earlier design by Richard Hodson (1831-1890), the Chief Engineer of the Thames Ironworks and Shipbuilding Company that had made the steam engines for the Admiralty Pier Turret. The contract for the widening of the old part of Admiralty Pier for the new railway station was given to Messrs Pearson and Son and signed on 14 May 1909. The contract price was £439,447 and the whole project was estimated to cost £600,000 using plans drawn up by DHB engineer Arthur Thomas Walmisley (1848-1923) with consulting engineer Arthur Cameron Hurtzig (1853-1915).

At the same time as Messrs Pearson and Son were given the widening of the Pier for the new station contract, they were given a contract to erect a temporary landing stage on the Admiralty Pier extension. The framework was open pile and to meet changes in tidal levels a two-tiered landing stage was attached. The landing stage was roofed, 20-feet wide by 800-feet long and principally designed for cruise liners. To minimise the disturbance to the cross-Channel passage services, two of the five berths on the original Pier were to be kept open until the landing stage was finished when one was to be demolished. The other berth was to be demolished when the berth was operational.

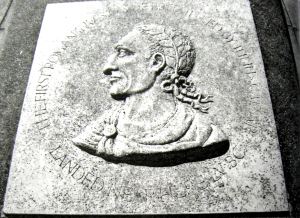

E Worsfold Mowll, Register of Dover Harbour Board. Dover Library

In order to pay for the projects DHB re-issued all its stock plus, on 11 July 1909, additional stock with an interest rate of 3.75%. To raise the income necessary to meet the interest payments and to go towards a sinking fund on a further loan of £1m, they applied to Parliament for an increase in the Passenger Tax. The passenger tax was 2shillings and 6pence (12½pence) and increased by 1shilling (5pence) on each Channel passenger embarking and disembarking. The interest on the £1m loan was agreed at 4% and the sinking fund 2½%. Worsfold Mowll, the DHB Register, giving evidence to a House of Commons selective committee, said that over above the individual Passenger Tax, 5shillings was received by DHB for every train that went onto the Admiralty Pier and £1 for every ship that tied up alongside. Both the increased Passenger Tax and the loans were agreed under section 27 of the 1906 Dover Harbour (Works etc.) Act.

Before work started on widening the Pier, South Eastern and Chatham Railway (SECR)obtained the lease from DHB for that part of the Pier at a nominal rent of £10 a year for 99 years but were responsible for building the new station. Work started on the widening on 5 July 1909 but on advice from DHB, Pearson’s initially concentrated on building the landing stage on the Pier extension. By the end of 1909, railway lines connected the landing stage and further down the Pier an oil tank was erected by the Admiralty, similar to the oil installations at the Eastern Dockyard. It could hold 110-tons of oil.

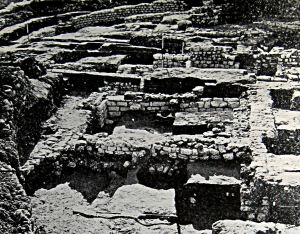

Block making at Shakespeare Beach circa 1900. Courtesy of DHB

The area to be reclaimed for the widening was 11.3 acres and Pearson’s made concrete blocks at Shakespeare beach, in the same way as the blocks had been made for the major construction of the Pier (see Admiralty Pier part I). Huon Pine was brought from Dover, Tasmania (see Transportation Story), to provide the timber staging. For the 2,260-feet sea wall each pile were placed 40-feet apart and driven into the seabed using a cantilever pile driver. On these, staging was erected and rails were laid for Goliath cranes, that lowered the concrete blocks into place. Titan cranes later replaced the Goliath cranes.

Admiralty Pier during widening for the Marine Station circa 1910. Dover Harbour Board.

The building of the sea wall required the relatively soft seabed to be removed. This was done using mechanical diggers lowered either by Goliaths or a floating crane. The excavated material was put into barges and dumped at sea. Workmen, in diving bells suspended from the Goliaths, levelled the seabed prior to laying the concrete blocks. As before, they were lowered by the Goliaths and set into position by divers. The wall had to stand by itself until in-filled so the base width was half its height. Once the 2,260-feet sea wall was constructed, infilling progressed by use of 1 million cubic yards of chalk brought from East Cliff. At the base of East Cliff, railway lines were laid to transport the chalk to Castle Jetty where it was loaded onto barges and taken to the Pier. The excavations at East Cliff served a dual purpose as a road was formed from the excavations that was to be the approach from Dover to a new exclusive residential estate at South Foreland, St Margaret’s(see Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Railway Part I). By the end of 1909 over 500feet of staging for the widening had been built.

To meet Admiralty requirements, a 6-feet high 4½-feet conduit to carry electric cables to the new station was constructed. This was from the Lord Warden Hotel to the seaward end of the reclaimed area but an unexpected difficulty was encountered. When the original Admiralty Pier was constructed this was from Cheeseman’s Head, where an ancient jetty had stood. It had been assumed that the jetty was demolished when the Pier was built in the mid-19th century. In fact the Cheeseman’s Head jetty had served as a foundation and was in a poor state. This had to be demolished and new foundations for the Pier laid before the required conduit could be constructed.

Hubert Latham – Sunday Graphic 01 July 1909. Dover Museum

All work stopped on 10 July 1909 when Hubert Latham (1883-1912) was expected to make the first crossing of the Channel by aeroplane. He was expected to land on Ropewalk Meadow, Aycliffe but only ticket holders were to be allowed into the intended-landing place. Therefore, DHB opened up the Pier allowing free access to the 2,000-feet long extension, together with the upper promenade of the original Pier. On the day, although it was blustery the Pier was packed but due to the strong winds Latham did not make the flight. He again attempted to make the flight on 27 July and free access to Admiralty Pier was once again available. Although crowded, work did not stop this time, though it probably did when sightseers saw Latham’s aircraft approaching. It came from a south-easterly direction and looked like an enormous seagull but to the sightseers did not seem high enough to clear the cliffs. Latham brought the machine round and tried to gain height but then dipped and dropped into the sea. The aeroplane struck the water just off the Pier extension and several ships and boats went to the rescue. Louis Blériot (1872-1936) had made the first successful crossing two days earlier on 25 July.

Admiralty Pier on a rough day from the Illustrated London News. Dover Library

The weather and the western entrance to the harbour remained a problem. In February 1910 storms had damaged many of the temporary buildings erected for the widening of the Pier. When similar weather condition prevailed on 7 October 1909, the Brigantine Osprey, was unable to make it through the western entrance and tried to get alongside the west side of the Pier, where a landing stage had been erected. She was wrecked with the loss of all but three of the crew. Coastguard Maurice Miller, wearing a lifeline, managed to get on board the wreck, erect a breeches buoy and rescued the three. For this he was awarded a Board of Trade Medal for gallantry for saving life at sea. For a time, during such weather, some packet ships had been diverted to Folkestone while other cross Channel and cruise services were directed through the eastern entrance to berth alongside the Prince of Wales Pier. On some days there were so many ships trying to get alongside that Pier they were forced to tie up two abreast and delays were frequent.

Edward VII shaking hands with Harbour Master John Iron Admiralty Pier March 1910 before leaving for Biarritz. David Iron Collection

On March 1910, while on his annual trip to Biarritz, France, Edward VII (1901-1910) collapsed and on 27 April returned to England by way of Dover. He was met by Harbour Master, John Iron (1858-1944), who wrote that the King did not appear at all well. Edward VII’s health continued to deteriorate and on 5 May, the Queen consort Alexandra (1844-1925) returned from Corfu, Greece, by way of Dover. The following day the King died. More than 50 ruling monarchs, crown princes, special envoys and ambassadors landed at the Pier to board special trains to take them to the funeral. King George V and Queen consort Mary’s coronation took place on 22 June 1911 and again the Admiralty Pier and special trains were in demand. Although packet ships had been using the new landing berth on the Pier extension for the coronation and the weeks after, it was not until 1 November that an official berthing trial took place. This was successful and in his speech after the ceremony, the Chairman of DHB, Sir William Crundall, said that with a depth at low water of 43-feet he expected that about 20 cruise liners a month would be tying up at Dover!

From 1890, Germany, under Wilhelm II (1888-1918), had been pursuing a massive naval expansion. It was this that had galvanised the British government into building the Admiralty Harbour as a base for the Royal Navy. In July 1911, Germany sent her gunboat Panther to Agadir, Morocco, supposedly to protect the country’s firms even though the port was closed to non–Moroccan businesses. The Admiralty reacted by, amongst other things, ordering the Camber, at the Eastern Dockyard, to be deepened, increasing the oil storage facilities there as well as converting Langdon prison, on the Eastern cliffs, into a Naval Barracks.

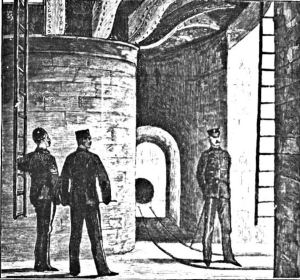

One of the Admiralty Pier Turret’s 6-inch MK VIIs guns mounted on the Pier. Nick Catford

Already, both the western and eastern entrances were equipped with a boom defence and a fort built at the head of the Admiralty was designated Pier Turret Battery. Further construction took place with two 6-inch MK VIIs guns mounted on the Pier. The new fortifications were armed with a mixture of breech-loading medium and light quick-firing guns that were mounted in concrete emplacements. Searchlights, barracks and magazines were erected, the sites of some still survive. However, the searchlights were a hazard to ships approaching or negotiating port entrances. Captain Dixon, the cross-Channel Marine Superintendent made representations to the military authorities who agreed to extinguish the lights when a warning blast was given by a ship. Unfortunately, these blasts were not always heard so it was agreed that ships would instead use flares.

The infilling for the new station was completed in February 1913 and was strengthened by over 100 ferro-concrete octagon shaped piles, 17-inches across the top with a cast iron shoe, driven through to the old seabed underneath the infilling. The piles varied in length, up to 62-feet and were driven into position by a 42-hundredweight (2.1 tons) monkey falling a distance of 4-feet 6-inches. The project had cost £375,000 and on 2 April 1913 Sir William Crundall laid the final stone. Following the ceremony Mr Moir, managing director of Pearsons, informed all those who had worked on the project they would be granted an extra days pay.

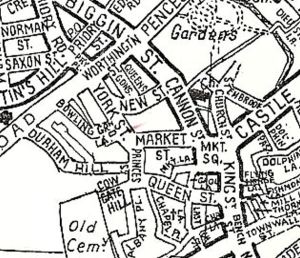

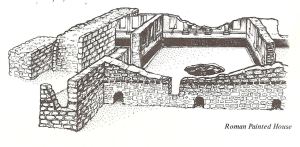

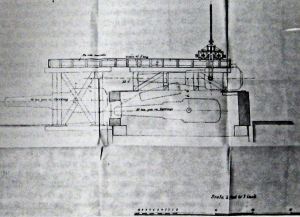

Marine Station with adjacent berths plan. May 1910

In the spring of 1912 tenders were invited for building the Marine Station, but as the projected prices were considerably in excess of estimates SECR had made, the company did not accept any tender and decided to build the station themselves. Sir Percy Crosland Tempest (1861-1924) designed the new station with four railway tracks and two island platforms, 700-feet long and 60-feet wide. The platforms were to have duplicate refreshment rooms and waiting rooms each 100-feet in length a general office and a post office. The edifice was to be topped with a 770-feet long braced arch roof. Adjacent there were to be berths for four cross-Channel steamers the access to which was to be made through covered walkways. The deep-water landing stage was to be 780-feet long and 20-feet wide with lower decks opposite to the centre of the vessels.

Building of Marine Station 15.11.1913. Dover Museum

On 24 May 1912, the Pilots gave up the Pilots Tower so that it could be demolished in order for a double set of railway lines to be laid to the new station. The tower was demolished in 1914 by which time the Pilots had bought and moved into No.1 the Esplanade. Work started on building the station and the contract for the piling was given to Considère Construction Company of Westminster. They used 1,300 x 18-inch piles along the whole length of the reclaimed area. The piles ranged from 38-feet to 72-feet long, ranged each side in groups of two and four to carry the foundations of the outside walls. A further 1,200 heavy piles were driven at the shoreward end of the site to carry the foundations of the station entrance and groups of piling were driven in for the various station buildings. Connecting ferro-concrete slabs were laid on the top of the piles along the whole length of the station wall foundations. Concrete rafts were provided for the station buildings. SECR’s usual contractor for such purposes, Messrs W E Blake Ltd of Fulham, built the walls and platforms for the station.

Admiralty Pier – Entrance steps were divided, the left took passengers to Marine Station, right to the Pier walk. Alan Sencicle 2015

By April 1913 work on the new station was progressing well with the Butterley Iron and Steel Company, Ripley, Derbyshire providing and erecting the steel framework. The depth of water for the berths was given as 16-feet at low water of spring tides and a coaling berth was in the course of construction. At each of the passenger berths, awnings extending as far as possible across the quay towards the ships were about to be erected. Access to and from the station was by steps on the opposite side of the road to the Lord Warden Hotel. The left side took passengers to the station, by the means of a footbridge, the right to the Admiralty Pier public promenade. The latter was reopened at Easter but was closed again on 1 October for the winter.

There had been several tests to assess the suitability of Dover harbour for the Atlantic fleet between 1909 and 1913 with special reference to the problems of entering the western entrance and the uncomfortable and sometimes difficult mooring conditions. These were found to be caused by opposing tidal surges rushing simultaneously through both harbour entrances creating cross currents. For this reason and in order to take submarines, the Camber had been deepened at the Eastern dockyard. With the widening of the Pier a further problem had become apparent, it exacerbated the sea swell along the entire length during heavy weather. At Rosyth on the Firth of Forth, Scotland, the Admiralty were building a much larger naval base and Vice-Admiral of the Fleet Prince Louis Alexander Mountbatten (1854-1921), announced that Dover would be a station for submarines based in the Camber and destroyers.

Admiralty Pier – the laying of track to the new Marine Station. Dover Museum

The stone front of the Marine station and the brick walls were completed in the early months of 1914 and the approach from what was planned to be a Viaduct access to the station was completed. By the end of July 1914, all of the building work of the Station was finished but on Saturday 1 August, Germany declared war on Russia, invaded Luxembourg and crossed the French frontier at several points. Ferries were crossing the Channel as often and as fast as they could, endeavouring to bring back home as many folk from France as possible. Winston Churchill, the First Lord of the Admiralty, issued the order to mobilize the Royal Navy on a war basis and aboard destroyers, moored in the harbour, crews were engaged in getting rid of all surplus woodwork in preparation for action.

As Germany moved into Belgium, Belgian refugees started to arrive, at first on ferries then on all kinds of craft. One night the Belgium Queen Elisabeth (1876-1965) and her three children arrived at the Pier incognito. Earlier the moveable assets of the state bank had arrived and were quickly taken to the Bank of England in London. The British Prime Minister (1908 to 1916), Herbert Asquith (1852-1928) and French Prime Minister (1914-1915) René Viviani (1863-1925), with Sir John French (1852-1925), who was appointed the Commander of the British Expeditionary Force on 30 July 1914, and Lord Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) Secretary of State for War, with others dined on board a British cruiser moored to the Admiralty Pier to discuss the events.

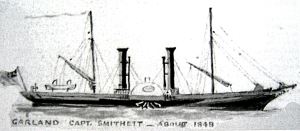

Marie Henrietta the nearest ship alongside Admiralty Pier circa 1899. Bob Hollingsbee Collection Dover Museum

At 14.30hrs on Sunday 2 August the Marie Henrietta tied up at the Pier having come from Ostend with 1,122 passengers on board. At 19.30hrs the Princesse Clementine arrived with a further 1,400 passengers from Belgium. That evening the Admiralty mobilised all the Fleet and at 19.00hrs, as the warships left the harbour, the Special Service section of the Cinque Ports Territorial Force arrived to operated the Coast Defence Searchlights at the Pier Turret Battery. At about the same time the first aeroplanes arrived at the Swingate military ‘aeroplane station.’

Admiralty Pier map showing the new Marine station and the landing stage

By Bank Holiday Monday, 3 August, it was clear that only a miracle could avert Britain being drawn into the conflict. At 03.00hrs, a telegram was sent to Southsea Castle ordering the Dover Unit of the Cinque Ports Territorial Force of Royal Engineers to return at once to help man the Pier Turret Battery. George V issued a Royal Proclamation calling up the Royal Navy Reserve, Royal Fleet Reserve and Officers and Men of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve.

The packed SECR ferry, Engadine, arrived from Calais and tied up on Admiralty Pier at 08.00hrs following which all Channel traffic from France was transferred to Folkestone. The Pier and the Marine station were then commandeered by the Admiralty and guarded by sentries. The last passenger ship to arrive at Admiralty Pier from Belgium was the steamer Rapide on Tuesday 4 August at 02.10hrs with 893 passengers on board. She left at 15.30hrs that afternoon for Ostend with six passengers, by which time Germany had declared war on Belgium. At 23.00hrs on 4 August 1914 Britain declared war on Germany in accordance with the written obligation of 1839 to uphold the neutrality of Belgium. World War I (1914-1918) had began and Dover became Fortress Dover (see World War I – the Outbreak).

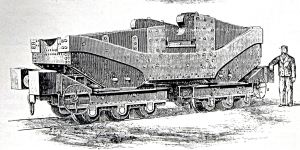

Spanish Prince being converted into a blockship, sunk March 1915. Alan Sencicle Collection

Both the western and eastern harbour entrances were already equipped with a boom defence and forts had been built on Admiralty Pier, the Eastern Arm and the Southern Breakwater to prevent enemy ships and submarines entering. It was believed, however, that the greatest threat to shipping would come from torpedoes fired from outside the western entrance. The quickest, cheapest and most effective way to block the entrance was to fill old ships with shingle and sink them across it. Initially the Livonian and the Montrose were chosen but the Montrose broke from her Admiralty Pier moorings, sailed out of the harbour and came to rest on the Goodwin Sands. She was replaced by the Spanish Prince.

Fortress Dover included the town and the entrance and exit was subject to restrictions as well as everyday aspects. These included the banning of street and harbour lighting, the result of which were fatalities from drowning. To combat this the whole of the dock area was surrounded by wire fencing, which reduced fatalities but made access, even in an emergency, difficult. In the Channel the first German submarines appeared around the middle of September 1914, sinking the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy, off Zeebrugge and the Dover Patrol was formed to defend the Strait of Dover. The work of the Patrol made the Naval Port of Dover the second most important Naval base in the British Isles. The port was also the base for the naval attacks on the enemy occupied Belgian coast and was designated the Homeport for ambulance ships.

First Expeditionary Force on the way to the front from Admiralty Pier – note the canopy. Doyle Collection

The demand on the station at Admiralty Pier and the quays increased dramatically as troops arrived by train and embarked for the Western Front. Those from camps nearer Dover, marched to the Pier, often through villages and streets lined with cheering spectators. The first of the thousands of troops to leave the Pier for France were the British Expeditionary Force under the command of Sir John French. He departed for the Front on 14 August from Admiralty Pier aboard the Sentinel.

It was not long after, the first of the wounded arrived at the Pier and on disembarkation were sent by train to hospitals further a field. On 10 December 1914 the Pier Turret Battery had their ‘first major encounter with the enemy’, when, at 05.30hrs a searchlight reflected off what was believed to be a submarine periscope and they opened fire. The Batteries along the Southern Breakwater took up the firing and the ‘periscope’ disappeared. It was later reported that four submarines had been seen, that two had sunk and the other two disabled. However, this was later shown to be the product of fertile imaginations and that no one was even sure if a periscope had actually been seen!

The injured walking and lying along the Menin Road following the Battle of 20-25 September 1917. Doyle Collection

Albeit, the berths on the Admiralty Pier were increasingly being used by hospital ships. The first hospital ships had been commandeered from the Great Western Railway Company’s Fishguard-Rosslare route. As more wounded arrived from the Western Front, pressure was mounted to complete Marine Station and from 2 January 1915 the station and the quays became the country’s main receiving hospital for the men wounded at the Front. Because of the nature of the arms being used it was expected that casualty rates would be high but the sheer number of maimed and injured men exceeded all expectations. At the Front the Royal Army Medical Corps, the Red Cross and the various medical and nursing organisations provided a high level of care. If a casualty survived the battlefield he would have a good chance of making it to Dover. In towns and cities throughout the country the number of hospitals proliferated with many commandeered buildings becoming centres of medical excellence such that the survival rate was high.

Marine Station. Medical symbol in recognition of the role the station played during World War I. Alan Sencicle 2015

As the War progressed more ships and large yachts were commandeered as hospital vessels. During the Battle of Loos in 1915 and the offensives of 1917 and 1918 the number of hospital ships arriving at the Pier and the trains leaving for hospitals elsewhere, increased dramatically. However, it was the Battle of the Somme (1 July to 18 November 1916) that the through-put of the wounded was at its highest. Up to nine hospital ships arrived each day and trains were continuously leaving Marine Station for London, packed with the injured, 24hours a day over a three day period. Those too ill to travel were taken to the Military Hospitals on Western Heights, Castlemount and elsewhere in the town. The Town Station was turned into a mortuary. On the façade of Marine Station – now Cruise Terminal One – are medical symbols especially carved as a tribute to the station’s role during World War I.

The Town Station could be used as a mortuary for on 19 December 1915 a massive landslide along the Warren, between Dover and Folkestone, blocked a mile of railway track. SECR, after consultation with the Board of Trade decided that the blockage could not be removed during the War and for the remainder the Admiralty used the Archcliffe and Shakespeare Cliff tunnels to store mines and shells for locally based warships. Trains in and out of Dover to London used the Canterbury line and due to an increasing number of ambulance trains and military trains the effects of wear and tear were causing delays. It was not until 11 August 1919 that the Folkestone line reopened. The advance of the German armies in Flanders in 1918, proved threatening and an attack on Dover was felt to be imminent. Infantry detachments were deployed at all times on the Breakwater and the shore at the foot of the piers. Trench mortars and machine-guns were fixed at every vital point including along the Admiralty Pier.

The War ended on 11 November 1918, Armistice Day, and on 27 November, King George V, Edward Prince of Wales and Prince Albert ( later George VI 1936-1952) arrived at Marine Station at 11.20hrs. Ten minutes later they boarded the Broke to be taken to Boulogne where they met Field Marshal Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928), before going onto Paris. In December the Field Marshal and a party of his Generals disembarked from the Termagant at the Eastern Dockyard and were transported to the Admiralty Pier station. Lining the route were Dover’s school children and at the station a civic address was presented by Mayor Fairley before the party boarded the 11.00hrs train to London. Over the next year a number of other very senior military personnel returned by way of Dover and were given a welcome appropriate to their status. These included Field Marshal General Sir Edmund Allenby (1861-1936) and the American General John ‘Black Jack’ Pershing (1860-1948).

The arrival of American President Woodrow Wilson at Admiralty Pier on 26 December 1918. Dover Museum

One of the most tumultuous welcomes was given to the American President Thomas Woodrow Wilson (1856-1924) and his wife Edith (1872-1961), who arrived from Calais at Admiralty Pier on the Brighton passenger steamer on 26 December 1918. This was the first visit to Britain by a US president while still in office and their ship had been escorted by the Termagant, six destroyers and a flotilla of other ships. Circling above, were British and French aeroplanes and on entering the harbour a Royal salute was fired from the Castle. At the Pier the East Kent Regiment provided a guard of honour and Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught (1850-1942), and Vice-Admiral Sir Roger Keyes (1872-1945) welcomed the President and his wife. Also on the quay were other dignitaries included officials from both Britain and the US plus Mayor Farley of Dover and other councillors. As the distinguished couple walked to the Marine Station a group of Dover school girls, wearing ‘Stars and Stripes’ dresses, strew roses in their path. At the station, Sir Archibald Bodkin (1862–1957), Dover’s Recorder, read an address emphasising the part America had played during the War. The President replied by thanking Dover for the part the town played and this was met with a resounding applause. Then the Presidential party left for London.

The first ship to leave Admiralty Pier for Ostend was the Ville de Liege on 18 January 1919

Although the War was over, the harbour was still in the hands of the Admiralty but the Commercial Harbour was managed by DHB. They had to deal with, at the best, years of neglect and at the worst, adaptations to the harbour that were not relevant to a passenger port. To make matters worse, they were £1m in debt from pre-war loans. On 18 December 1918, a few of the restrictions on civilian crossings to France were lifted but due to the devastation on the Continent travelling there was difficult. Civilian crossings to Belgium resumed on 18 January 1919 when a channel at Ostend harbour was cleared following the destruction and the partial blocking by the Dover Patrol on 10 May 1918. The first ship on that crossing, the Ville de Liege departed from the Admiralty Pier. Two days later the remaining restrictions on the crossings to Calais and Boulogne were lifted. However, naval ships in the process of being repaired occupied the majority of the Pier berths.

Returning soldiers from Europe were billeted in rest camps around the town while awaiting demobilisation but the paperwork took time. In January 1919 a large group of War tired servicemen marched to the Town Hall (now Maison Dieu) demanding to be allowed to go home and more personnel were drafted in to help with the paperwork. Then, on 12 June 1919, 200 soldiers of the Black Watch Regiment billeted in the Oil Mills on Limekiln Street, still awaiting demobilisation, were marched to Admiralty Pier. On arrival, they were told that they were to embark for France to help in clearing up operations. The men, without any fuss, did an about-turn and marched back to the Oil Mills. Shortly after they too were demobbed!

Victoria, one of the cross-Channel ships commandeered for War service. Following a refit she was returned to Dover in January 1919. Dover Museum

The British cross-Channel ships returned to Dover in January 1919, after refitting. All had been commandeered for war service and the first to return was the screw turbine steamers Invicta (II) launched in 1905 and the Victoria (II) launched in 1907. By the summer season of 1920, the number of passengers using the cross Channel services had almost returned to the pre-War level. This provided the much needed passenger tax revenue for DHB. In one week in March, 8,598 people crossed the Channel netting £644 passenger tax. That year Dover Corporation applied to extend the Borough boundaries to include all Dover Piers and was the subject of an Inquiry in March. This led to a High Court case before Mr Justice Darling later that month, when Marine Station was asked to be included in the Parish of Dover and was granted. DHB went to the Court of Appeal but lost.

Arrival of the Unknown Warrior at Admiralty Pier on 10 November 1920. East Kent Mercury

Following the first Armistice Day in 1918, the idea of interring, in Westminster Abbey, one of those who had been killed during the War but whose identity had been lost was born. This developed into honouring all the 908,000 servicemen who had lost their lives. On 10 November 1920, the body of the Unknown Warrior was brought across the Channel in the British warship, Verdun. The oak coffin was provided by the Undertakers Association and draped with the Union Jack. On Admiralty Pier were dignities representing Royalty, the Armed Services and the Church as well as the Mayor and Councillors of Dover. As the coffin was carried from the ship the Royal Fusiliers Band played Elgar’s Land of Hope and Glory and all were visibly moved. The coffin was then transferred, with great ceremony, into the waiting SECR passenger luggage van number 132. Surrounded by uniformed servicemen standing at attention. It was taken to London and then to Westminster Abbey, where the Unknown Soldier was finally laid to rest.

Admiralty Pier promanade still as popular as it was in the 1920s Alan Sencicle

The fine weather of the summer 1921 brought a large number of visitors to Dover and on 19 July the full length of the promenade on the Admiralty Pier was opened. This proved the most popular of the tourist attractions that summer. Regrouping of the many of British private railway companies took place on 1 January 1923 and Southern Railway came into operation. This included the two railway companies that served Dover, which had semi-amalgamated in 1899 to form the South Eastern and Chatham Railway Companies Management Committee.

Admiralty Pier railway turn table prior to demolition in March 1935. Dover Library

On 24 June 1923, at a meeting with Dover Corporation, Southern Railway announced that they planned a new engine depot, marshalling yards, goods yard and the rebuilding of the Customs sheds on the West Quay on Admiralty Pier, near Marine Station. The highly controversial Viaduct, which had been the main reason for the demolition of much of the maritime Pier District, opened in 1922. The Limekiln Street bridge opened in June 1923 and the level crossings at both Elizabeth Street and the Crosswall closed making access to the Marine Station and Admiralty Pier smoother for the road user. To widen access for the motorist, in March 1935, the railway engine turntable near the Admiralty Pier gates was demolished and a new one built close to Shakespeare Beach.

After protracted negotiations on 9 September 1923, the Admiralty Harbour was transferred by Act of Parliament to DHB, with the Admiralty retaining some rights. The most important was that should the Defence of the Realm create the necessity, the harbour, without compensation, was to revert to the Admiralty. Although the Marine Station had opened the station on the Pier extension was still in use but in October, a violent south-westerly gale almost swept a train off the Pier overturning one carriage and smashing windows in others. Three members of the King’s Dragoon Guards were severely injured and two porters suffered broken bones.

Twin ‘Crest of a Wave’ sculptures by Ray Smith on Dover seafront looking towards the western entrance and on the right the Prince of Wales Pier. Alan Sencicle

The problems with the western entrance and the uncomfortable and sometimes difficult mooring conditions within the harbour remained a problem. In November 1925, DHB sort for an Act of Parliament to permanently close the western entrance. They argued that closure would give smooth water and would do much to shelter the Marine Station in easterly gales. Further, a survey of the harbour had shown that the Eastward Drift – the deposit of shingle brought by tidal flows from the west – was shallowing the Harbour. Further, the shingle came in almost entirely through the western entrance. The Admiralty opposed the Harbour Board Bill in Parliament, arguing that it was essential for the Navy to have two entrances in the harbour, making reference to the caveats within the Act of 1923. Parliament, however, gave greater weight to Dover being a commercial port and the Bill became as Act. However, experiments using a model showed that closing the western entrance would create more problems than already existed and so the project was abandoned.

Jack Elks (1885-1950) Kent Coalminers Leader

The General Strike began on Monday 3 May 1926 and the Dover Central Strike Committee was formed under the leadership of the Kent Miner’s secretary, Jack Elks (1885-1950). The railway, including shipping services to the Continent, stopped and also at the Packet Yard, where ship repairs took place. By the end of the second day most workers in other Dover industries were on strike. On Wednesday, just after midday, the strike was being called off and on the Friday a national railway settlement led to a partial resumption of national services. In Dover, Southern Railway resumed its full rail and shipping services but the miners remained on strike. Coal shortages led to the passage crossings cut to one English ship, one French ship and one Ostend ship daily.

At the beginning of the strike Southern Railway had arranged for imports of American coal if necessary. They put this into operation and the Danish steamer Nordkap arrived on 17 June with 5,000tons of coal that was discharged directly into railway trucks on Admiralty Pier. Coal shipments then arrived regularly, long after the miners returned to work at the end of the year. On several occasions there were two trans-Atlantic coal ships discharging coal at the same time and the amount of coal landed was approximately a quarter of a million tons. This enabled the Southern Railway to run all its summer rail and cross-Channel services that year. However, one of the berths on Admiralty Pier was badly damaged on 22 June when one of the coal carrying ships, Blythmoor struck and badly damaged the landing stage. The ship’s hawse-pipe was damaged and the bow plates stoved in.

In the early 1920s, James Ryeland of George Hammond persuaded the Royal Netherlands Steamship Company to call in at Dover on their way to and from the Caribbean and South America. Instead of berthing on Admiralty Pier the cruise company embarked and disembarked their passengers by tender in the outer harbour. The Hamburg-Amerika Line Toledo called on 1 December 1924 on her way from Germany to South America and did tie up on Admiralty pier. However, due to the poor state of the harbour and the facilities available the Toledo only made a few more calls before moving to Southampton.

Hamburg-America Liner Patria with tender Lady Saville late 1930s. David Ryeland

By 1927 the Royal Netherlands Steamship Company’s smaller ships were calling at Dover every two weeks and on 26 March that year their new and largest vessel Simon Bolivar, docked at Admiralty Pier. James Ryeland and the Mayor, Captain Thomas Bodley Scott R.N., welcomed her. Later that year Dover became a port of call for the company’s liner Surinam, that went to South America and then onto New York and their new steamer the Cettica made an initial call. Although other shipping lines started to use Dover as a port of call, with some mooring alongside the Prince of Wales Pier, the general preference was to moor in the outer harbour. In 1931 DHB purchased the Penlec, a liner tender from the Great Western Railway Company, to help with the transfer of passengers and supplies. She was joined by the Lady Saville when the cruise liner service picked up in the middle 1930s.

In July 1928, Captain Stuart Townsend chartered the 386-ton coastal collier Artificer and from the Eastern Dockyard operated a car-carrying cross-Channel service between Dover and Calais. This was primarily for passengers with motorcars with the cars being loaded by crane. Southern Railway were already operating a car carrying service from the Admiralty Pier and again, cars were loaded by crane. Albeit, in response to the Townsend operations they launched, in 1931, the Autocarrier. She was originally designed to be a cargo ship but was altered to carry cars as the Railway Company’s first designated cross-Channel car-carrying ferry.

Canterbury. Alan Sencicle collection

The first contingent of troops from the occupied Rhineland disembarked on Admiralty Pier on 24 September 1929. Although an official welcoming party had not been arranged, Dover folk turned out and gave a rousing welcome. The Seaforth Highlanders based in Dover were also there and played lively Scottish airs before the contingent boarded a special train taking them to Catterick, north Yorkshire. Three months earlier, in May 1929 the Golden Arrow train service was introduced between London and Dover and at Admiralty Pier the last word in pre-War luxury, the 2,910 gross-ton Canterbury launched in 1928, was waiting to take passengers across the Channel to France.

In 1930, DHB invited tenders to remove the World War I blockships close to the Admiralty Pier and the western entrance. The Harbour Master and salvage expert, John Iron, was given the job and planned to remove the gantries and then pump out the ballast to raise the ships and take them to the Eastern Dockyard for scrapping. The Livonian was lying nearest to Admiralty Pier so she was dealt with first. The work started at the end of February 1931 and the site was finally cleared on 6 May 1933. The project was fraught with danger so it was decided, after removing the gantries, to leave the Spanish Prince where she lay. Later, during a gale, the Spanish Prince shifted position and became less of a hazard.

Train Ferry Dock underconstruction. Dover Library

Work started in August 1933 on a Train-Ferry dock at the base of Admiralty Pier. The specifications for a concrete dock 414-feet long and 72-feet wide, with a minimum depth of water of 17-feet to a maximum of 36-feet, were drawn up by George Elson, Chief Engineer of Southern Railway. John Mowlem & Co along with Edmund Nuttal, Sons & Co were given the construction contract. The Gates were made by William Arrol & Co – leading Scottish civil engineers, and worked on horizontal hinges fixed below the dock sill. Two rail-lines were laid to connect the dock to the main rail-line with William Arrol & Co erecting a link span to connect the railway lines to the ships. The whole project cost £231,000.

Hampton Ferry. Dover Library

Southern Railway ordered three ferries built by Swan, Hunter & Wigham Richardson, Newcastle-on-Tyne. They were the Twickenham, Hampton and Shepperton each 2,839 tons, length was 359-foot; 63-foot 9-inch beam and 12-foot 6-inches draft. Coal-fired and with a service speed of 16 knots, each ship was designed to take 12 sleeping cars and 500 passengers or approximately 40 goods wagons. The formal crossing was on Monday 12 October 1936 when trains were shunted aboard the Hampton and at the helm was Captain Len Payne. Distinguished guests included he Home Secretary – John Allsebrook Simon, 1st Viscount Simon (1873-1954), the French Ambassador, British and French railway officials and the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports: Major Freeman Freeman-Thomas, 1st Marquess of Willingdon (1866-1941). The night service between London and Paris was officially inaugurated by the French Ambassador on 5 October 1936. The facilities for carrying motorcars was inaugurated on 28 June 1937 on a small floor (garage) above the train deck accommodating approximately 20 cars.

At the time that the Admiralty Pier extension was completed, a fog gun, or more correctly a detonator signal fired by electricity, was operated from the Pier lighthouse. In foggy weather the gun went off every two minutes but in February 1934, DHB issued a notice to mariners announcing that after 1 August that year the fog gun would be replaced by a diaphone fog signal sounding a blast of two seconds duration every 10seconds from the lighthouse. At the eastern end of the Southern Breakwater, an electrically operated bell giving one stroke every 7½seconds was sounded. A small diaphone on the Southern breakwater was already in existence and gave a 3second blast every 10 seconds.

From the mid-1930s the number of cross-Channel passengers and cars rapidly increased at the same time as the number of freight ships were increasing. Such was the situation, along Admiralty Pier, that ships were queuing to get alongside. Plans were made to increase the number of berths from eight and included using the Eastern Dockyard. The idea was given added impetus in January 1939 when Prime Minister (1937-1940) Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940) together with Foreign Secretary (1938-1940) Edward Wood, 1st Earl of Halifax (1881-1959), travelled through the port using the Golden Arrow service, for Rome. There they met Italian Prime Minister (1922-1943) Benito Mussolini (1883-1945) in order to persuade him not to become involved in any conflict. However, on 3 September 1939 when World War II (1939-1945) was declared, the Pier, along with the rest of the harbour, again come under the Admiralty as part of Fortress Dover

Captain Henry Percy Douglas naval officer who worked with Vice Admiral Roger Keyes in preparation for the Zeebrugge Raid. Chairman of DHB 1934-39 and buried at sea.

The final cross Channel ship to leave Dover and the Admiralty Pier was the Canterbury of the Golden Arrow Service. The port closed on 5 September. Shortly after the embarkation of the British Expeditionary Force to the Continent commenced. On the 7 November, Vice-Admiral Sir Henry Percy Douglas (1876-1939) who had resided in Dover and was the Chairman of the Dover Harbour Board (1934-1939), was buried at Sea, his cortége leaving from the Pier. Known as Sir Percy Douglas, he was a British naval officer who specialised in surveying and from April 1917 to January 1918, he worked with Vice Admiral Roger Keyes in preparation for the Zeebrugge and Ostend Raids.

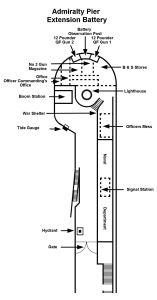

Throughout the War, the officer responsible for co-ordinating all of Dover’s defences be they on land, sea or in the air was the Fortress Commander based at the Castle. Admiralty Pier Turret battery, as in World War I was based at the Turret with a second gun emplacement on the Pier extension. Initially railway carriages were brought in to provide accommodation for the personnel until new quarters were built. On the night of 28-29 November 1939, a cliff fall along the Warren blocked the railway line from Dover to London via Folkestone. A similar fall to that which blocked the line during the latter years of World War I. This time the blockage was cleared within five months. At about the same time, the Royal Navy requisitioned the two Train-Ferries Hampton and Shepperton for minelaying. Between December 1939 and May 1940, mines were laid in the Channel and southern North Sea by the two ferries working with two Royal Navy minelayers.

Although, during the inter-war period, the Admiralty had objected to the blocking of the western entrance. However, when taking command of the harbour, as they had in World War I, they decided to block the western entrance. The War Sepoy, a Z-Type tanker, built by William Grey and Co. of West Hartlepool under the WWI Standardised Shipbuilding Scheme was one of the ships used. She was 412-foot long, 52-foot beam and 5,800 tons gross and had been badly damaged in the harbour during an air raid on 19 July 1940. Beyond repair, she was filled with concrete and towed into position and sunk on 7 September. The steamer, Minnie de Larringa that had been sunk in the port of London by German bombing, was refloated, towed round to Dover and sunk in the western entrance on 5 February 1941.

Dunkirk 1940 Troops arriving in Dover having been evacuated. Doyle Collection.

On the Continent in May 1940 the French and Belgium ports fell to German onslaught and the British Expeditionary Force were forced onto the beaches of Dunkirk. Masterminded by Vice-Admiral Bertram Ramsay (1883-1945) Dover Fortress Commander launched Operation Dynamo or the Dunkirk Evacuation, as it is known. A fleet of 222 British naval vessels and 665 other craft, known later as the ‘Little Ships’, went to the rescue. Vice Admiral Ramsay, his dedicated staff, the rescue ships and their crews, the harbour officials, the Southern Railway staff, East Kent Road Car Company employees, and townspeople of every vocation, worked ceaselessly. Almost nine hundred vessels, some manned by civilian volunteers, began their epic task of plying to and fro across the Channel, loaded to the gunwales – far exceeding safety limits, with exhausted troops. Only the Admiralty Pier was deemed suitable for the intense disembarkation but throughout, with little room for manoeuvre, the two Dover Harbour Board tugs, Lady Duncannon and Lady Brassey, pushed and pulled the ships from their moorings for either rapid repairs or essential refuelling.

Maid of Orleans during the Dunkirk Evacuation came under heavy attack. When she arrived in Dover ‘blood was running down her sides.’

Between 26 May and the 4 June 1940, the exhausted men, their clothing in tatters and many wounded, arrived at Dover. Most were disembarked on the Admiralty Pier but due to the numbers returned to England many were disembarked on the Eastern Arm and the Prince of Wales Pier. The cross-Channel ship, Isle of Thanet had been requisitioned as a hospital ship and was the first such ship to go into Dunkirk. She made several trips along with the other Dover passage ships including the Autocarrier, Biarritz, Canterbury, Hampton Ferry, Shepperton Ferry, Maid of Orleans and the Dinard. While standing off the Mole at Dunkirk the Canterbury was badly battered and on reaching Dover was hastily repaired and returned to pick up more troops. The Maid of Orleans packed with troops, on leaving Dunkirk was heavily attacked from the air and it was reported that when she arrived in Dover, ‘blood was running down her sides.’

At height of the Evacuation, 31 May, 4 hospital ships, 25 destroyers, 12 transport ships, 14 drifters and minesweepers, 6 paddle steamers, 5 trawlers, 16 motor yachts, 12 Dutch skoots and more than 20 other vessels disembarked 34,484 men from the beaches of Dunkirk. On that day, the vessels alongside Admiralty Pier’s berths were three abreast disembarking soldiers. Most of the vessels were battered, some beyond recognition. Between 26 May and 4 June 1940, 338,226 British and Allied troops were evacuated from the beaches of Dunkirk and all told, nearly 200,000 British and Allied troops passed through Dover. On 12 May, during the evacuation, the town and port were declared a ‘Protected Area’ and following the evacuation Marine Station was ‘closed’. In June 1941, the Station was ‘opened’ to military traffic going to the Second Front following Germany’s invasion of Russia.

Sandhurst, hit while moored in the Harbour during the Battle of Britain, 29 Jul 1940. Michael Harmer

The Dunkirk Evacuation was followed, between the 10 July and 31 October 1940, by the Battle of Britain when the Germans tried to gain supremacy over the Channel in preparation for invasion. It is said that Adolph Hitler had given the order, before the Battle began, that the port of Dover was to remain serviceable. This, it was said, was because he planned to cross the Channel by sea and receive Britain’s surrender from George VI on Admiralty Pier. Nonetheless, the harbour, including the Pier, came in for heavy, unremitting, attacks from land – across the Channel, sea and air.

On 28 August, with the Prime Minister Winston Churchill in attendance, an experimental Parachute and Cable (PAC) anti-aircraft device was fired from the Pier. A rocket projectile, its function was to be fired at enemy aircraft and in tests had reached a height of about 600-feet, trailing a wire behind it. A sudden jerk of the wire released a small parachute with an explosive charge attached that would damage the aircraft. Possibly due to wind effects, the experimental projectile’s wires became entangled and it plummeted to the ground without achieving anything.

British and Norwegian Mine Laying Fleet that operated from Admiralty Pier. David Ryland

The British and Norwegian mine laying fleet operated from Admiral Pier and from the end of July 1940 barrage balloons were sited around the town including Admiralty Pier. These were designed to keep enemy aircraft above a certain height to reduce accurate bomb-aiming. Although they were effective in their intended role they also caused friendly fatalities. In the early hours of 30 June 1941, a Blenheim of the 59 squadron, based at Detling, returning at low level from a bombing raid in France, hit a barrage balloon cable above Admiralty Pier. The plane crashed into the sea and only the pilot of a crew of three was found. Pilot Officer J N Whitmore was buried with full military honours at Hawkinge Cemetery. On 15 September 1941, in the early afternoon, a Dornier bomber destroyed twelve trawlers tied up against the Admiralty Pier. The motor torpedo boat, Botanic was hit killing the captain and five men and seriously injuring several others. On 5 November that year Flight Sergeant Spallin of 609 squadron, was returning from a sortie in his fighter when he too hit the balloon on Admiralty Pier. Unable to get out of the cockpit the Flight Sergeant died when his plane sank.

Marine Station following the attack of 25 September 1944. Dover Library

In order to release troops for the D-Day landings, on 1 April 1944 the Admiralty Pier Turret Battery was given over to the Dover Harbour Board Home Guard supplemented by the Dover Home Guard. In June the VI pilotless flying machine (doodle bug) was brought into use by the enemy. Carrying a 1-ton war head propelled by a rocket motor that once stopped, the warhead was designed to fall to the ground doing untold damage. At the end of August one exploded on Admiralty Pier. At this time, Allied troops were drawing closer to Calais and the attacks on Dover town became intense. Marine Station came in for sustained shelling and on 25 September it was all but destroyed.

Following D-Day, 6 June 1944, the Train-Ferry Dock became a hive of activity and on 29 June 1944 the Twickenham, with a large gantry, protruding over the stern and carrying a transporter crane capable of carrying 84 tons, delivered the first load of British-built locomotives to the Continent. Both the Hampton and Shepperton, were similarly adapted, joining their sister ship in transporting engines to Calais and Boulogne when they were freed from occupation.

When peace returned, the number of ships tying-up at Admiralty Pier escalated and approximately 400,000 troops, including prisoners of war – one of which was this author’s Father – disembarked at the Pier. To process them, three transcript camps were set up in Dover with the troops being sent to London and beyond. Often there were thirty full trains a day carrying returning men. As the troops were arriving in Dover, Belgium refugees, who had been in England for the duration of the War, were returning home.

Marine Station circa1950s-1960s with war memorial on the right. Dover Museum

On 10 July Dover Naval Command had ceased to exist as an independent force coming under the Nore command and on 30 November 1946, Dover ceased to be a naval base. Previously, on 18 September 1945, the Admiralty and the War Office handed the port back to DHB but due to enemy attacks it was in a much worse state than after World War I. Marine station was handed back to Southern Railway and once emergency repairs and renovation had taken place, returned to operation in April 1946. Another plaque was added to the station’s War Memorial, that reads, ‘And to the 626 men of the Southern Railway who gave their lives in the 1939-1945 war.’

Autocarrier I. Dover Museum

Southern Railway started a restrictive cargo service on 9 August 1945, from Folkestone using the Maidstone and the Hythe. The first cross-Channel ship to return to Dover was the Invicta, which made the crossing on 26 December 1945 but as a troop carrier. It was not until April 1946 that she underwent a refit and returned on October taking over from the Canterbury to operate the Golden Arrow service. The Canterbury had returned in April after her refit and the Golden Arrow service was resumed. Despite austerity on 11 October the 100,000th post-war passenger boarded the service. The Canterbury was given another refit and went to Folkestone where she inaugurated a new Folkestone-Calais service on 1 December. The Autocarrier returned to Admiralty Pier and first crossed to Calais on 15 May, while the rival Townsend Brothers Cromarty Firth, operated from the Eastern Dockyard, did not start until 1 April 1947.

The ferry service, Regie Voor Maritiem Transport (Belgium Marine), having started a service to Folkestone, transferred to Admiralty Pier on 7 October 1946 with the Prinses Josephine Charlotte and Prince Baudouin. Following repatriation, all three Train-Ferries were fitted with oil-fired boilers and the service was resumed in May 1947. The Autocarrier was transferred to Folkestone and the newly converted Dinard arrived at Admiralty Pier for the car-carrying Boulogne passage on 1 July 1947. The Dinard had a turntable on the main deck that enabled the ‘first car on to be the first car off!’ However, following the August bank holiday, when 5,156 passengers travelled from Dover to the Continent, it was announced that the American Loan crisis was to curtail foreign travel for pleasure purposes. Coming into fully operation on 1 October the crisis severely reduced the number of passengers until the ban was lifted in April 1948.

Invicta, the first ship to use the western entrance after it was opened on 26 April 1963. Alan Sencicle collection

Although, the western entrance was to be cleared of blockships by October 1945, the Admiralty appeared to be in no hurry, citing poor weather and other demands on their salvage boats. A survey undertaken on 2 May 1950 found that the War Sepoy was buried under the hull of the World War I blockship, Spanish Prince but was finally lifted in August 1962. The Minnie de Larringa was raised in August 1960 and on 26 April 1963, the Golden Arrow vessel Invicta left Dover through the re-opened western entrance. However, the Spanish Prince collapsed during the operations and shifted position and her new position was marked by a Cardinal buoy, to the east of the western entrance. Her superstructure continued to break-up naturally but she remained a potential hazard. Salvage work was undertaken in 2010 and the old blockship was cut up where she lay and taken ashore by tug and barge.

On 18 March 1946 the first post-war cruise liner, the Royal Netherlands Line Maaskirk bound for the West Indies arrived in Dover. She anchored in the outer harbour and passengers were transferred by tender. When the 9,000 ton liner Umgeni came to Dover on 7 and 8 July 1948 to embark passengers, mails and stores for South Africa she was berthed on the Eastern Arm. However, the number of cruise ships decreased due to the lack of a tendering service and poor conditions on the Piers. Over the next forty years cruise liner traffic fluctuated but it was rare for any to use the Admiralty Pier.

Admiralty Pier – Cars being hoisted onto ship for export. Dover Transport Museum

In 1950, for the first time since before the War, the number of fare paying passengers crossing the Channel, exceeded 1million. Cargo handled was approximately 750,000-tons. Two years before, in 1948, DHB had put forward a plan to move cross-Channel ferry operations to the Eastern Dockyard and use Admiralty Pier, supported by the Wellington and Granville Docks, for cargo. However, the state of the harbour, shortages, lack of money and a major confrontation between the DHB and Dover Corporation slowed the process down. The seeds of the latter had been sown during the dark days of World War II, when the council had devised a plan for the future of the town following the War. Town planner, Professor Abercrombie, was hired to give weight to this plan and although he recognised the importance of Dover harbour, the Professor agreed with the council stating that ‘the lifeblood of a town of the nature of Dover is undoubtedly its industry.’ He went on to recommended the demolition of East Cliff and Athol Terrace to be replaced by a wide access road to the Eastern Dockyard that had been earmarked for industrial purposes.

DHB vehemently opposed the plan but was over-ruled in court. Albeit, in November 1949, against strenuous opposition from Dover council, DHB promoted a Parliamentary Bill to create a specialised Car Ferry terminal at the Eastern Dockyard for the bulk of passenger services. Permission was given in February 1951 and it was estimated that the facility would cost £500,000. The railway ferries berthing at Admiralty Pier dominated Dover’s ferry industry and DHB centring freight only services at the Pier did not go down well. Southern Railway had ceased when the railway network was nationalised on 1 January 1948, becoming British Railways Southern Region. The only other ferry operator was Townsend Brothers, based at the Eastern Dockyard, with one ship operating only in the summer months. In 1950 they bought the Halladale and converted it to carry 350 passengers and 55 cars. The following year the Company used a converted Bailey bridge as an unloading ramp introducing roll on – roll off (Ro-Ro) to the Dover ferry industry.

Dinard 1946 when she was commandeered as a troop ship. Dover Museum

That year, 1950, Southern Region’s Dinard carried a record number of motorists from Admiralty Pier. To deal with the throughput, Southern Region opened an additional Customs hall at the Pier, which could accommodate 10 cars at a time. The old customs hall could only handle 6 cars and less could be handled at the Eastern Dockyard. On 14 August, the day the new customs shed opened, eighty-five cars disembarked and were cleared in 80-minutes. Nonetheless, the development of the Eastern Dockyard as a car-ferry terminal continued and was formally opened, as Eastern Docks on the 30 June 1953 by the Minister of Transport (1952-1954), the Rt. Hon. Alan T Lennox-Boyd MP (1904-1983). Along with the Chairman of DHB – H T Hawksfield and the Register/General Manager – Cecil Byford as part of the ceremony, he was driven aboard the Dinard!

Admiralty Pier – Connecting bridge that took passengers into Marine Station. AS 2015

Admiralty Pier remained as Dover’s main ferry terminal with the eight berths and the number of passengers still growing fast. This was partly due to the introduction of restrictive Travel Allowances that encouraged people to take short breaks instead of longer holidays on the Continent. Initially the Travel Allowance was £100 in cash but in November 1951 the allowance was reduced to £50 per person and from January 1952, only £25, banking was also affected. However, the cargo trade continued to expand and at Granville and Wellington Docks the ancient Strond Street almost disappeared and Northampton Street did. This was to enable the quays to be widened and commercial buildings erected. From 1952 the Golden Arrow service was transferred to Folkestone.

The number of passengers coming through Dover continued to increase year on year and in September 1958 the 2millionth passenger passed through. Albeit, an increasing percentage of passenger traffic was going through the Eastern Docks but the Belgium ships on the Ostend route and the French National Railways ships tended to be berthed on the Admiralty Pier. The number of passage ships using Dover as a home base continued to increase but Southern Region by 1958, for economic reasons, had not introduced a new ship to Dover since the Lord Warden in 1952.

Admiralty Pier Turret from the Prince of Wales Pier. AS 2015

In May 1960 the DHB, to complement the new public walk along the seafront to the North Pier, opened the Turret Walk on Admiralty Pier. The seafront walk went under the Prince of Wales Pier and was named after Charles II. This was in honour of the tertiary centenary of the King’s landing on Dover beach following the Restoration of the Monarchy. For the Turret Walk, a false roof had been put on the Turret raising it by three courses of brick to be level with the new footpath. One of the former MK gun positions was converted into a shelter with windows looking out to sea and the other became a raised circular platform with seats on top and a safety rail around it.

Admiralty Pier – with cross- Channel ferries berthed alongside. The Reine Astrid is in the foreground. circa 1960s. Dover Harbour Board.

Albeit, the ferry companies were increasingly complaining that the berths were uncomfortable at Admiralty Pier compared to those at Eastern Docks. This was investigated in 1963 and four schemes were suggested to ameliorate the long term problem. The solutions offered could have been used in conjunction with each other or individually but all were expensive. At the time it was not uncommon to see five ferries berthed alongside Admiralty Pier with another ship in the Train-Ferry Dock and four ferries at the Eastern Docks but DHB said that they could not afford to put any of the solutions into operation. However, a refurbishment of the berthing facilities at the Pier was instigated and included the demolition of the Admiralty oil installations dating from World War I. During demolition, the installations burst into flames but the prompt action of the Southern Region firemen stopped what could have been a major catastrophe.

Freightliner Service that did not include the Channel Ports

On 27 March 1963 the British Railways Board published their two part The Reshaping of British Railways, better known as the Beeching Report after Dr Richard Beeching (1913-1985) the Chairman. His report was designed to make the British railways financially profitable and the upshot was the closure of approximately 33% of the rail network. This was mainly feeder lines that cut off communities and industry from the main rail transport system but led to a saving of a mere £30m. Part of the report appertained to freight transport that ultimately led to Freightliner being set up. The company, now privatised, is still a major carrier of container goods but due to pressure from Kent County Council (KCC), no freight carrying rail routes were designated to pass through Kent to the Channel Ports. Further, although the trunk road routes were poor to the East Kent coast nothing to ameliorate this was envisaged. It was expected that container and passenger Continental traffic would go to other UK ports and East Kent would become a tourist destination in its own right.

Dover Corporation, in 1973, turned its attention to the former Pier District, by this time all but demolished to create vehicle access to Shakespeare Beach. The council voted to improve the remaining terrace properties along Beach Street, where once the Town Station had stood. Apparently ‘phone calls were made from Harbour House, Waterloo Crescent to the Town Clerk’s office, in the former DHB headquarters at New Bridge House. DHB already had provisional plans for the area in conjunction with replacing the old Viaduct leading to Admiralty Pier and dealing with the increasing freight traffic. In 1974 freight traffic was greater than car/passenger traffic. The DHB official went on to say that a new ferry berth was to be constructed at the Admiralty Pier knuckle – the first at the Pier since the Train-Ferry Dock in the 1930s.

A new Viaduct and associated roads were constructed but the railway lines along Admiralty Pier extension were cut off. The new £700,000 berth opened on 28 June 1974 specialising in heavy goods vehicles roll-on/roll-off (Ro-Ro) traffic. That same day saw the inaugural crossing of the Belgium car ferry Prins Laurent. However, in July the car ferry Normannia was badly holed after hitting an underwater object near Admiralty Pier and was taken out of service. Back in June 1949, the Maid of Orleans had arrived in Dover to great fanfare. She was the first vessel on the Channel crossing fitted with a Denny Brown stabiliser and although she initially worked the Folkestone – Boulogne service, in the winter she was the relief ship on the Golden Arrow service. A traditional passenger ferry she returned to Dover in August 1972 on the rail-connected passenger service from Admiralty Pier but in 1975, she was sold. Her replacement was the Caesarea, launched in 1960 and sold in 1981 to be replaced by the Caledonian Princess, launched in 1961.

Belgium Marine inaugurated a Jetfoil passenger service between the Admiralty Pier and Ostend in May 1981. A special berthing pontoon, costing £1.3m was built by Mears with DHB, Sealink Ferry Company (former Southern Railways) and Belgium Marine sharing the cost. The two Boeing Jetfoils Princesse Clementine and Prinses Stephanie, arriving in July and made the crossing in 100 minutes against 3hours 45 minutes taken by ferries. Costing £14m each, the Jetfoils had the capacity to carry 316 passengers. In order to provide a protective breakwater around the berthing pontoon, a sheet pile wall, 66 metres in length, 10 metres wide and 16 metres high was constructed. The steel piling was provided by British Steel’s Middlesbrough Plant. New 10-tonne blocks, made on Shakespeare Beach, were used to form a wave absorbing slope. The service saw a throughput of over 100,000 in the first year and British Rail said that they would provide a rail link for the service. The Jetfoil project however, proved shortlived.

Nord Pas de Calais. Dover Harbour Board

Number 3 berth on Admiralty Pier was fitted with a new fendering system in 1982 at a cost of £109,000. Three years later the berth was enlarged to take vessels up to 23.0-metre beam and cost £½m. This was in order to take enlarged Belgium ferries on the Ostend crossing. The Train-Ferry dock closed on 8 May 1987 by which time the Train-Ferry ships only carried rail freight and freight lorries. However, an agreement between Sealink, British Rail and French Railways to build a new Train-Ferry berth. This was at the knuckle of Admiralty Pier, constructed by W A Dawson and cost £8.9m. It was designed for 23-metre beam ships and as part of the scheme new rail sidings were laid by British Rail for £0.35m. The loading bridge and machinery was built by Cleveland Bridge, cost £34.6m and the link span was computer controlled to meet the different states of the tides. The Nord Pas de Calais was the only ferry designated to use the berth and was designed to carry trains on the lower deck and 690 metres of Ro-Ro freight vehicles above. However, the Great Storm of 15/16 October 1987 reeked havoc on the construction time and the service finished operating in 1994 with the opening of the Channel Tunnel. The bridges were cut up and sold for their recyclable metal value.

Admiralty Pier coverered section once gave access both to the Pier and Marine Station. AS 2015

Admiralty Pier has always been popular for anglers, with the Dover Sea Angling Association (DSAA), running competitions during the inter-war period. The association introduced Sea Angling week in 1947. Tragedy occurred in September 1959 when 11-year old sea-angler John Saich of Temple Ewell was swept off Admiralty Pier by 30-foot waves and drowned. Albeit, following DHB opening the Turret Walk, the Pier became even more popular for anglers but the hurricane force winds on the night of 15/16 October 1987 rendered the walkway unsafe and it was closed. DSAA negotiated a fifteen-year maintenance contract with DHB and carried out repairs costing a total of £177,000. The Admiralty Pier was reopened to anglers and walkers in November 1989. In return, DSAA run the Admiralty Pier walk under licence from DHB. Access to the walkway is behind Lord Warden House, up the flight of steps and through a hall that was once shared by passengers going to Marine Station.

Marine Station early 1990s. Dover Express

In 1990, DHB was approached by Fred Olsen Cruise Line of Harwich with a view to Dover becoming one of their home ports. This seemed like a particularly good idea as the threat of the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994 was of great concern to DHB. They sent officials to Miami to test out the market to see if Dover was viewed as an ideal UK port of call for cruise liners. The feedback was excellent and the group put forward the proposal of a cruise liner terminal. By that time Marine Station had been renamed Dover Western Docks but its usage had diminished and British Rail’s 99 year lease with DHB was about to come to an end. Following the closure of Marine Station on 24 September 1994, it was found that the Grade 2 listed building was in a far worse condition than envisaged and local architect, Trevor Gibbens, produced plans for refurbishment.

Former Marine Station now Cruise Terminal I. Passenger stair entrance to platforms. The railway lines have been covered with tarmac to create parking spaces. LS 2010

A £10m refurbishment scheme was instigated by DHB that included removing the railway lines outside the former station to make car and coach parking space. Because the building is listed, the railway lines inside are still there but buried beneath the tarmac. A mezzanine floor was created as a passenger lounge with a tinted glass roof. The dedicated quay length for the new cruise terminal was 432 metres and dredging gave minimum 10.5 metres depth of water. The terminal opened in 1996, and the author travelled on one of the 98 cruises vessels that used Dover that year. By 1998, there had been 140 cruise liner calls and DHB decided to build a second terminal. In 1999 work started on Cruise terminal 2 on what had been the site of the Train-Ferry berth. Although the quay length at Cruise terminal 2 is the same as Cruise terminal 1, the facility has seating for 700 passengers and 2,035 square metres of baggage handling space. The combined cost of the two terminals was £28m.

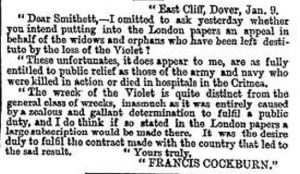

The A20 was widened and rerouted across the west of Farthingloe Valley along the cliffs and into Dover close to Western Docks and Admiralty Pier, and along to Eastern Docks, in the early 1990s. Costing £24m it was not until 1993 that it actually opened. At the time, although the transportation of goods in container lorries had been increasing for thirty years, locally little thought was given to what was happening in the European Parliament. This was regardless that the key person was a Dovorian and an old boy of Dover Boys’ Grammar School – Francis Arthur Cockfield (1916-2007). It was Cockfield who created the Single European Market that allowed, amongst other thing, the free movement of trade. By the end of the century traffic congestion, due to the number of lorries on the A20 was more than a major problem, a problem that since has escalated to overwhelming proportions.

DHB, initially reacted by purchasing the former Old Park Barracks site and turning it into a Port Zone with a lorry park. For a number of reasons this did not materialize and much of the site was sold, mainly for housing. They then considered turning part of the Farthingloe Valley over to a lorry park but as the area is protected, this failed to gain planning permission. In November 2000 they looked at the possibility of creating a new dock area, to be called Westport, along Shakespeare Beach and restoring a rail link to the port. Although Shakespeare Beach was technically a Dover amenity, public access had long since been made difficult due to much area landward of the Beach being given over to freight lorries.

Western Docks refurbishment proposal. Dover Mercury 01.02.2007 The blockship was removed in 2010

For the year ending 2005 the number of freight lorries passing through Eastern Docks was 1.98million and the number forecast per year by 2034 was 3.9million. In March 2006, DHB announced that a second ferry terminal would be built and that it would be part of a full redesign of the Western Docks. This was published in February 2007 and was envisaged to include the reclaiming (filling in) of the Granville Dock and Tidal Basin and the creation of four new ferry berths and a marina. Three of the new ferry berths would be on the east side of a widened Prince of Wales Pier and the fourth on the west side on the site of what had been the hoverport. The marina was envisaged to be on the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier, landward of the new ferry berths, with a waterway access across the Esplanade / Marine Parade to Wellington Dock. However, following costing, it was decided that the latter would be too expensive. On reappraisal it was decided that Wellington dock would be land locked with the water released via sluices but with no thought given to Dover’s flooding problems (see Flooding).

The Grade II listed Admiralty Pier light house and traffic control light array. AS 2015

It was proposed to lengthen Admiralty Pier by a further 75 to 100 metres in order to reduce the century old problems. The access to the Admiralty Pier walkway was to be refurbished with the emphasis on restoring what had been the historic pedestrian access to the Marine Station. The work for the full proposal was scheduled to be completed by 2012-13 and to cost approximately £300m. The Admiralty Pier, was listed as Grade 2, along with associated structures including the steel lighthouse designed by Richard Hodson (1831-1890) – see above – on 16 December 2009. The former Marine Station, now Cruise Terminal 1, was refurbished in 2014 along with the pedestrian access to Admiralty Pier promenade.