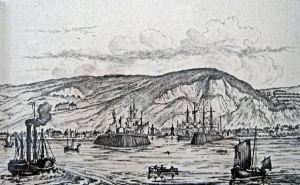

Dover harbour c1850 – the nearest dock is Wellington Dock with the Bason on the right and the Tidal Basin on the left. Dover Library

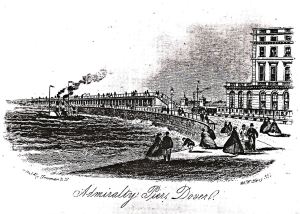

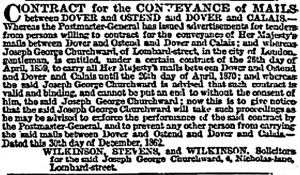

After considerable pressure on the government by Dover folk, local politicians, the Harbour Commissioners and the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852), for Dover to become a Harbour of Refuge, in 1847 the Admiralty Pier was started. This was to be the western pier of the Harbour of Refuge and although plans were proposed and accepted by government for an eastern pier, due financial reasons they did not materialise. Time passed and the Harbour Commissioners, faced with the prospect of larger steamers going to other ports such as Folkestone, wanted to carry out major improvements to the existing harbour in order for such ships to berth within the harbour. At the time the harbour consisted of the Bason (inner basin), Wellington Dock and the Tidal Basin. They therefore submitted a Bill to parliament in 1861 to this effect. Instead of being given approval and sanctioned to borrow money to pay for the work, the Harbour Commissioners were reconstituted and the Dover Harbour Board (DHB) was created. Not only was borrowing restricted but the main source of revenue for the Harbour Commissioners – passing tolls, a tax on shipping traversing the Strait of Dover – was discontinued.

The new DHB could do very little except scrimp and save and keep spending to a minimum. Eventually they raised sufficient money to apply for a loan to carry out the much-needed improvements. This they achieved with parliament allowing sufficient borrowing for major work to being in 1871. This was on the existing Bason and on completion it reopened as the Granville Dock. In order for the larger steamers to enter the new Dock, it was necessary to widen the entrance and that meant that the existing majestic clock tower, which stood at the entrance had to be demolished. The actual clocks were cleaned and a new clock tower with a lifeboat station along side was built at the western end of the seafront and completed in 1877. Shortly after the quay space was increased alongside Wellington Dock and in 1888 its gates were widened.

In August 1872, a DHB Board meeting, presided over by the then Deputy Chairman Steriker Finnis (1817-1889), was held. The members of the Board included, Samuel M Latham and John Birmingham representing Dover Corporation and James Staat Forbes and C W Eberall of the South Eastern Railway (SER) and the London Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR) respectively. There was unanimous agreement to adopt a scheme to create a commercial harbour designed by Sir John Hawkshaw (1811-1891) that utilised the existing Admiralty Pier and enclosed 340 acres of sea space. The sea space was to be ‘deepened so as to admit steamers of draught of not less than the Holyhead class.’ Other improvements were to include a covered walkway from both the SER Town Station and the LCDR Harbour Stations. Each of the stations was to have a landing wharf, so that, ‘passengers could embark and disembark in comfort, whatever the condition of the weather.’

For this they would need grants and to borrow so DHB, Dover council and local politicians kept up the pressure on government to sanction the proposition. However, for all their efforts very little was accomplished. Yet cross-Channel ships were still increasing in size and number and the port was not able to accommodate them at all states of the tide. Out of pure frustration on 3 October 1890, with Deputy Chairman William Layton Lowndes in the DHB Chair, the Board voted to undertake the building of the much-needed Harbour of Refuge and Commercial Harbour themselves. DHB Register, James Stilwell, drew up a Parliamentary Bill for authorisation to borrow £300,000. Additional finance, Stilwell said, would be raised by the introduction of a passenger tax similar to the type imposed by the French government to raise money for harbours in northern France. Sir John Coode (1816-1892), of Coode, Son and Matthews, Consulting Engineers, 9, Victoria Street, Westminster, designed the proposed Commercial Harbour.

The proposal was for a deep-sea harbour outside the north and south pier heads enclosing 56-acres with depths ranging from 15-feet to 40-feet at low spring tides. It was to be bounded on the western side by the existing Admiralty Pier plus an extension of 560-feet to shelter the eastern pier. On the eastern side, a pier 2,760-feet in length that started in a southerly direction and curved towards the south-west giving an entrance 450-feet wide facing east was envisaged. As the prevailing winds are from the south-west the commercial harbour was to be sheltered by an overlap of the extended Admiralty Pier. Within the harbour would be a water station – a covered space to accommodate four or five cross Channel steamers. There would be a connection from the shore over which the trains would pass to go alongside the cross-Channel ships. Part of the proposal was to remove or incorporate the ruins of the partially built Tudor breakwater and mole. Known, along with a number of other names, as the Mole Head, this was a continual shipping hazard near the entrance to the Tidal basin.

In 1891 the DHB successfully obtained the Act for the construction of the Commercial Harbour that allowed them to levy a tax of 1-shilling (5pence) on each Channel passenger and to borrow. Parliament also agreed to lease DHB the existing Admiralty Pier for 99-years but the Act contained a caveat. The approval of several named departments had to be sought and the contract price confirmed before full approval could be given. DHB sought approval from the stipulated bodies and put the eastern pier proposal out to tender. The stipulated departments were the Admiralty, the War Office, the Board of Trade, and the Office of Woods and Forests. Approval was given by all except the Admiralty who were uncommitted either way. The best contract price was £410,400 and the full estimate for the project was £600,000. The submission was presented in August 1892 and parliamentary approval was given for the eastern pier but not for any alterations to the Admiralty Pier.

The building contract for the eastern pier was awarded to John Jackson (1851-1919) of 2, Victoria Street, Westminster. Born in York, Jackson studied engineering at Edinburgh University under eminent mathematician Peter Guthrie Tate (1831-1901). In 1875, shortly after graduation, Jackson set up his own company and quickly gained a reputation as a structural engineer. Known for his ‘hands on’ approach, Jackson was later appointed to work on the construction of the Admiralty Harbour and the Dover and Martin Mill Railway Line. He was knighted in 1895. Civil Engineer John Kyle (1837-1905) was appointed the resident engineer at Dover under Messrs Coode, Son and Matthews.

The landward section of the pier, called the viaduct throughout the construction process, was designed to be 1,260-feet of open iron framework. This was to enable free water circulation within the new harbour as there was a strong eddy current setting from the east towards the head of Admiralty Pier for much of each tide. because of this, the open ironwork, it was anticipated, would prevent the silting up of the Tidal harbour outside the Granville and Wellington docks. The sub-contractor for the ironwork was Messrs Head, Wrightson & Co engineers and iron founders, of Thornaby-on-Tees and Teesdale Ironworks, Stockton-On-Tees and the total amount of iron used for the viaduct was 3,000 tons. The final cost for the ironwork was £414,000. Head, Wright & Co had undertaken work on the Granville Dock and were later to build the lighthouses on the Southern Breakwater.

Block making for Admiralty Pier – Concrete poured into wood moulds that opened at each side when set. Courtesy of DHB

The sub-contract for the concrete blocks for the solid pier was given to Messrs Coode, Son and Matthews who besides designing the new pier, were considered ahead of their time in harbour construction. The method used to make the blocks effectively piloted that used to create the concrete blocks to build the later Admiralty Harbour. A blockyard was set up between the root of the new pier and the Wellington Dock using one large mixer – see Admiralty Pier part I – the extension – for the details of how they were made. Each block for the pier was 12-feet by 6-feet and 4-feet 3-inches high and when the blocks were ready they were conveyed along the pier on a tramway and placed into position on the solid pier by a Titan crane. This was known to being able to lift 62½-tons over a radius of 100-feet. The actual building of the new pier only required a 60-foot radius and the blocks did not exceed 22-tons. All round, on the sea facing side, each block was bonded with granite, to protect them from damage by ships.

The approach to the new eastern pier began with an inclined root from the Esplanade eastward of the present Clock tower. The Clock tower and Lifeboat station had been rebuilt in 1877 and after much deliberation were rebuilt again to the west of their original site to make room for the root of the eastern pier. The deck level of the iron-structured viaduct was 19-feet above high water at spring tides in order, it was planned, to lift it above the reach of the sea during the heaviest of gales. Starting from the root, the open iron viaduct was arranged in bays and was to rest upon three piles driven deep into the seabed, filled with concrete. Surveyors had said that the piers nearest the shore would be on a bed of sand and gravel that rested on the chalk and gradually tapered away towards the deep water. The piers supporting the outer section of the viaduct would be driven straight into the chalk.

Attached to the iron cylinders were to be three rows of latticed girders supported by wrought iron piles securely braced together to ensure rigidity. On the girders, the roadway was to be formed of corrugated plating three-eighths of an inch thick riveted together to form a continuous table. The corrugations were filled with concrete and on this paving, blocks of Jarrah timber were to be laid. Jarrah timber is a large sized hardwood found only in the south west of Western Australia. The viaduct was to have a uniform width of 30-feet throughout its length, with two footpaths each 6-feet wide and a central roadway of 18-feet. They consisted of Portland cement concrete laid upon the ironwork and protected by an exterior coating of French asphalt. Locally made iron was used for mouldings, curves and guttering and handrails were fitted on each side for the entire length. As the approved design of the pier was to enable it to be used by promenading pedestrians, at three points there were to be open iron seats and in the middle there was to be a covered resting area 100-feet long.

The 1,500-feet long solid pier was to be attached to the open iron viaduct and was to consist of concrete blocks, faced with granite and grounded in 3-feet of chalk. The top width was 35-feet and the bottom section, resting on the seabed, was 45-feet. The coping level of the solid section of the pier was 10-feet above high water at spring tides, corresponding with the Admiralty Pier. The width was again 30-feet throughout its length, with a central roadway of 10-feet wide and a footpath on the west side 6-feet wide. On the eastern side there was to be two parapets, one above the other, to match the west side of the Admiralty Pier at that time. The pier was to take a south-easterly direction until the Head was reached, when it was to be more southerly with the outer portion south-south-west. The Head was to be circular 55-feet in diameter on which a lighthouse was to be built of the same material. The blocks of the Head were to be bonded, joggled and cramped together. Along the back of the solid work was to be a protective apron consisting of two rows of concrete bags, each bag weighing 14-tons, which were used to preserve the chalk foundation from the corrosive action of the sea. The difference between the higher viaduct and the solid pier was an incline of one in forty.

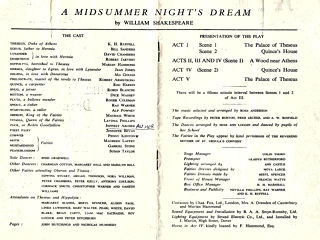

Dover council and DHB spent £’000s decorating the town for the Prince of Wales, (later Edward VII, 1901-1910) who was coming to lay the foundation stone of the eastern pier of the projected Commercial harbour. The weather, however, on Thursday 20 July 1893 was atrocious with high winds and driving rain. His Royal Highness arrived at the LCDR Harbour Station a few minutes before 13.00hrs where he was received by the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1892-1895), the Marquess of Dufferin and Ava (1826-1902) on behalf of DHB. The town was represented by the thirteen times Mayor of Dover (from 1886 to 1910), Sir William Crandall (1847-1934) and Dover Member of Parliament (1889-1913) George Wyndham (1863-1913). Also in attendance was Major-General Lord William Seymour (1838-1915) – Commander of the South Eastern District and numerous other dignitaries.

On the Prince’s arrival a Royal Salute was fired from the Drop Redoubt, on the Western Heights and accompanied by the Marquis, the Prince, in the State carriage led a procession of 37 horse drawn carriages to the already laid approach of the proposed Pier. There a tented awning had been erected and a crimson carpet laid. On each side of the carpet, leading to the entrance of the awning, was a guard of honour composing of the Cinque Ports Artillery Volunteers and room for 1,500 spectators, 850 of which had seats. Inside the awning was the foundation stone and seating for the accompanying dignitaries.

When all the dignitaries were seated, the late Sir John Coode’s son, also called John and an engineer, gave a short description of the project. In a cavity of the foundation stone were laid two bottles, one containing 1893 dated coins of the realm and a brief statement of the circumstances under which the stone was laid. The second bottle contained newspapers describing the proposed event and both bottles were covered by a plaque listing the names of those involved in the design and construction of the pier and the senior dignitaries attending that day. John Jackson then handed the Prince a silver trowel and an ivory mallet with ivory handles. Mounted on the end of the handles was the crest of the Prince of Wales in solid gold. Cement was placed on the lower stone over the two bottles and the Prince smoothed it with the trowel. A brass plate was placed underneath on the foundation stone with the inscription:

‘The Trowel is of massive silver picked in with gold, with a carved ivory handle with the Prince of Wales crest mounted in solid gold at the end. On the trowel is engraved the following: Presented to His Royal Highness the Prince of Wales by John Jackson, Contractor, on the occasion of the laying of the Memorial Stone July 20 1893’

Then engineers lowered the upper stone in place, which the Prince tapped with the ivory mallet. This stone carried the following inscription:

Prince of Wales Pier Foundation Stone first laid 20 July 1893 relaid 1954 to replace the original badly damaged during World War II. LS

‘The first stone of this new harbour was laid by H.R.H. the Prince of Wales, K.G. 20th July, 1893. Engineers Coode, Son and Matthews; contractor, John Jackson.’ The present plaque was put in place in 1954 following World War II and reads: ‘The first stone of this new harbour was laid by H.R.H The Prince of Wales K.G. 20 July 1893 Engineers Coode, Son & Matthews. Contractor John Jackson. This plate covers the original stone damaged by enemy action 1 May 1943.’

During the ceremony it was announced that the new pier was to be called ‘The Prince of Wales Pier,’ and afterwards the procession of carriages made their way, in the pouring rain, to the Town Hall (now the Maison Dieu). Although the weather was awful, the streets were crowded with well wishers and in Cannon Street 6,000 school children were standing on tiered benches. As the Prince approached, the children ‘raised their voices to invoke blessings on the Royal visitor.’ Accompanied by a band, they then sang ‘God Bless the Prince of Wales.’ Afterwards each child was given a bag containing a piece of cake and an orange. In the Market Square, Mayor Crundall (1847-1934) stopped the procession and gave the Prince a formal welcome to Dover. Much to the delight of the crowds, the Prince responded with a long eloquent address that won the hearts of all the onlookers.

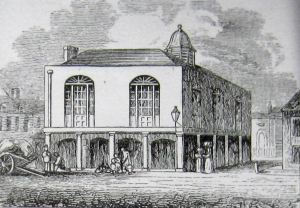

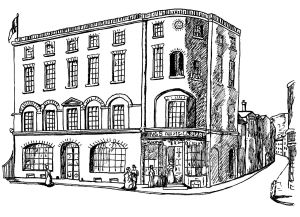

The Former Dover Town Hall where Edward the Prince of Wales was entertained on 20 July 1893. AS 2013

In the Town Hall the Prince, along with 480 guests, sat down for a sumptuous meal and at 15.30 he and his retinue left to take the train back to London. On the way the entourage passed through Dover College. There the headmaster, Reverend William Cookworthy Compton received His Highness, and during the subsequent conversation the Prince requested that the boys be given a week’s holiday! The Royal personage, just before 16.00hrs, left from Priory station for Victoria station, London. For the remainder of the day, although the weather remained miserable, there were a considerable number of activities including a regatta, swimming races, fireworks and the pubs were allowed to stay open until midnight. In the evening gas lit illuminations were switched on throughout the town.

It was not long after the foundation stone was laid before the first major construction problem was encountered. When the first pile was driven in, it sank into the soft seabed without trace! A second one was tried, further out, and this did the same. It was then decided to sink hollow cast-iron cylinders placed 40-feet apart and to then fill them with concrete. Although this worked, it delayed the construction. Nonetheless, by the autumn of 1893, the iron viaduct was progressing well and it was estimated that the poll-tax of one-shilling on all cross channel passengers would raise £16,000 that year. However, there was concern that the Pier was a potential shipping hazard so on 21 September two green lights were fixed to the sea end staging. A cardinal buoy was also placed at the seaward edge of where the staging for the viaduct was expected to reach.

A year later with the iron viaduct almost complete the first submarine block of the solid section of the Pier was laid on the seabed. Approval, however, for the proposed extension of the Admiralty Pier had still not been received from the Admiralty and both DHB and the council were becoming increasingly anxious. At the time, the Admiralty were taking a close interest on events on mainland Europe. On 18 January 1871, Germany had unified under the country’s first Chancellor, Otto von Bismarck (1815-1898), which changed the balance of power in Europe. Bismarck had strived to keep the peace but in 1890, Wilhelm II (1888-1918) effectively sacked him and then pursued a massive naval expansion. This galvanised the British government to consider the construction of a National Harbour on the south coast and until the go ahead and the location was decided the Admiralty were not committing themselves.

1895 saw the appointment of a new Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports, the former Prime Minister, Robert Arthur Talbot Gascoyne-Cecil, 3rd Marquess of Salisbury, by virtue of which he was the Chairman of Dover Harbour Board. By May that year 1,100-feet of the 1,500-foot solid section of the Pier had been built and that month the Admiralty announced its decision. The port of Dover was to be a base for the Royal Navy and a National Admiralty Harbour was to be built that would enclose the whole of Dover bay! The first Naval Works Act was passed in 1895 when it was estimated that the Admiralty Harbour would cost £3,500,000 and the proposal made it necessary to alter the plans for Commercial Harbour especially the Prince of Wales Pier.

The major and most expensive change was at the Head of the Prince of Wales Pier. Although the original design remained the same, the Head was straightened and carried forward making the now straight Pier 2,910-feet long. The parapets that had been built on the solid section were removed with only those around the Head remaining. On the Head, approached by a flight of granite steps, was the lighthouse. Built of granite, it was topped with a cylindrical lantern room on which was a metal weather vane. The road and footpaths were to be commensurate with the iron viaduct of the Pier. The Admiralty Pier extension was to be 2,000-feet long, paid for by the Admiralty and to be use for Admiralty purposes. For some time later, it was agreed that the remainder of the proposed Commercial Harbour works were to go ahead but other changes precluded them reaching a conclusion and these included leaving the the dangerous Mole Head rocks as they were.

Further, another unforeseen problem was becoming increasingly worse due to the ongoing construction of the Prince of Wales Pier. The area between the Pier and Admiralty Pier was increasingly subject to heavy swell that, at times, made it impossible for ships to berth alongside the Admiralty Pier such they were diverted to the rival port of Folkestone. To try and deal with this, a meeting was convened in November 1898 between the DHB, the two railway companies – SER and LDCR – and the Continental railway companies whose ships used Dover harbour. It was agreed that until the Admiralty Pier extension was long enough to intercept the Prince of Wales and thus creating calm water, there would be major problems due to adverse tides. At the time of the meeting, work had not begun on the Admiralty Pier extension but high priority was given and work started a month later. The Admiralty, sympathetic to the situation, made assurances that the extension would be completed in less than two years.

In August 1896 the Undercliff Reclamation Act received Royal Assent. This Act was for laying out land on the South Foreland, near St Margaret’s, where a new ‘Dover’ was to be built (see Dover, St Margaret’s and Martin Mill Railway Line part I). A syndicate of three had been formed to promote the Bill, one of which was Sir William Crundall – Mayor of Dover 13 times between 1886 and 1910. The second, John Jackson – who was building the Prince of Wales Pier. The other was construction engineer Weetman Dickinson Pearson, 1st Viscount Cowdray (1856-1927). His company had won the contract to build the Admiralty Harbour. In 1886, William Crundall had been appointed to the Harbour Board as the Board of Trade representative. James Stilwell (1829-1898), DHB’s Register, who had successfully piloted the Commercial Harbour scheme through parliament died in May 1898. Local solicitor and an adept organiser, Worsfold Mowll, who was a close friend of William Crundall, succeeded him. In the original proposal for the Prince of Wales Pier, James Stillwell had envisaged laying a railway line along the Pier and to have a landing stage for Continental passengers on the east side. On the west side, nearest to the Admiralty Pier, was envisaged a landing stage for use by Atlantic liner traffic and Mowll reminded Crundall of this. Together, with the knowing backing of Jackson and Pearson, they suggested to the Harbour Board that Transatlantic-shipping companies should be contacted.

In March 1901 the Deputy Chairman of DHB, William Layton Lowndes, suggested that another member of the Harbour Board should deputise for him on the grounds of his advanced age and Sir William Crundall was elected to take this role. On 9 April, at the request of the Marquis of Salisbury, King Edward VII (1901-1910) endorsed the decision. That month, Sir William Crundall and Worsfold Mowll together with DHB engineer Arthur Thomas Walmisley and Harbour Master Captain John Iron travelled to Brussels. This was on the invitation from King Leopold II of Belgium (1865-1909) to discuss proposals to increase the speed of the postal services that were carried on Belgium packet ships out of Dover. During the visit, the deputation put forward the plan for Dover becoming a port for transatlantic shipping and the notion was well received. On 23 August the German Bismark-class 3,000-ton corvette, Stein, paid a formal visit to Dover and was warmly welcomed by Mayor William Barnes, Town Clerk – Wollaston Knocker, Sir William Crundall, Worsfold Mowll and Captain Iron. The captain of the ship, Commander Burcham, was entertained to lunch by Major General Hallam Parr (1847-1914), Commander of the South-Eastern District.

On 3 September 1901, the deputation of four plus John Coode of the firm Messrs Coode & Son were at Potsdam Palace, Germany, making representations on Dover becoming a port for transatlantic liners. There they met with Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was wearing the uniform of a British Admiral. In attendance were the German Secretaries of State, Baron von Richtofen and Admiral Alfred von Tirpitz (1849-1930) and Herr Weigland with Albert Ballin (1857–1918), Director-Generals of the Norddeutscher Lloyd line and the Hamburg-Amerika Steamship Companies respectively. The Kaiser had a billiard table prepared so that charts and relevant papers could be spread and Sir William made the presentation. Afterwards the Dover deputation were entertained to a luncheon at the Palace and the following morning they left for The Hague for discussions with board members of the Dutch Atlantic Service.

In early January 1902, Richard Reid Dobell (1836-1902), of the Canadian government, came to Dover where he met with Sir William Crundall to discuss using Dover for transatlantic crossings and was shown round Prince of Wales Pier. In an unofficial capacity was Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman (1836-1908) the leader of the Liberal Party that was in opposition at the time. He was staying at the Lord Warden Hotel. Although Mr Dobell was killed a few days later following a fall from a horse while visiting his son in Folkestone, Sir Henry Campbell-Bannerman reported the positive outcome of the meeting to the government.

Commerative memorial for the completion of the Prince of Wales Pier 31 May 1902 where the viaduct meets the solid Pier. AS 2015

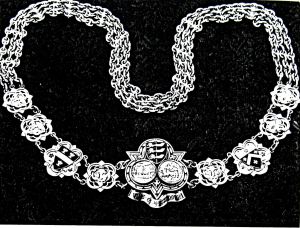

By the end of November 1901 the contractor’s railway was removed from the Pier and with the exception of the asphalting of the roadway on the viaduct portion, all the work was finished. The Prince of Wales Pier was formerly handed over to DHB on 1 January 1902 and on 14 February the cranes and other contract artefacts were sold. The formal opening took place on 31 May by the Marquess of Salisbury when a Completion Stone was laid at the point where the viaduct joined the solid section. In attendance were all the members of the Harbour Board: William Layton Lowndes, Sir William Crundall, Sir Myles Fenton, (1830-1918) – General Manager of SER, Sir Edward Leigh Pemberton (1823-1910), George Frederick Fry, Henry Peake and Worsfold Mowll. Also there was Sir John Jackson and engineers Coode, Son and Matthews. On completion the Pier was 2,910 ft long with an open viaduct of 1,260 feet, the remainder being of solid masonry. The depth at low water varied from 25-feet to 35-feet. The pier had cost £570,000 to build, met by the issue of £400,000 debenture stock, plus £170,000 in temporary loans to be paid for by the poll-tax.

SER and LDCR had merged in 1899, forming the South Eastern and Chatham Railway Company (SECR) and by a loop through the Pier district, the two lines were joined together. At the time, DHB had submitted a Bill to Parliament for building the envisaged ‘Water Station’ with four railway tracks and berths for four cross-Channel steamers all under cover between the Admiralty and Prince of Wales Piers. The final estimated cost was £1,750,000 and to help to pay for these works an increase in the poll tax on cross-Channel passengers was sought. The poll-tax was to be increased from 1shilling to 2shillings 6pence per head. Tagged on to this Bill was the proposal to widen the Wellington dock gates in order to admit the newer larger steamers into the dock. The Bill was given Royal Assent.

By November 1900, five transatlantic shipping companies had notified DHB that they were interested in making Dover a port of call, one of which was the Hamburg Amerika Line. Their recently launched Transatlantic liner Deutschland, drew 30-foot of water, while the White Star Line, recently launched, Celtic, drew 33-feet, so both could berth alongside the Prince of Wales Pier. More importantly, they could berth at low water of a springtide with 3-6-feet to spare! This meant that the railway line, envisaged by James Stilwell, was of paramount importance but this would need a wider and stronger Wellington dock bridge to accommodate a railway line and bear the weight of a railway locomotive. This, it was estimated would take two years to build while it would take four years to build the ‘Water Station.’

The ‘Water Station’ was put on hold and SECR agreed to lay a single-track railway line onto the Prince of Wales Pier from the joining loop to the Pier. On the Pier a 500foot long landing stage would be built on the east side where the Transatlantic liners would be accommodated. This was on the opposite side from the original plan but had been brought about by the building of the Admiralty Pier. The landing stage would have a wooden canopy that covered both the landing stage and the railway platform to provide cover for the passengers in all weathers.

Cross-Channel steamers berthed on the west side of the Pier and the first to do so was the Princess Beatrice, on 12 July 1902. However, comparatively few cross-Channel vessels used the Pier as the back up facilities were on the Admiralty Pier and so that was infinitely more preferable. In the plans submitted to parliament for the Prince of Wales Pier, it was stated that there would be a promenade for the general public and throughout the building this had been the understanding and, indeed, the gates had a pedestrian access for all to see. However, the gate was shut and padlocked. Increasingly the general public became vociferous, including writing to national newspapers. Worsfold Mowll promised that access would be available when final work was completed and cited that testing of the electric lamps was the cause of the delay. On 1 January 1903 the lock came off the gate while a wooden turnstile was erected and then the gate was locked again.

The gate remain locked until July 1903, when it was opened to coincide with the arrival of Émile Loubet (1838-1929), the French President (1899-1906). Britain’s relationship with France had fallen to a low ebb by 1898, due to the Alfred Dreyfus Affair – a French military officer of Jewish descent was falsely accused of treason and heavily punished (1894-1906) – and the Boer War (1899-1902). Thus, from Dover’s perspective, the visit by the French President was seen as an important economic step. The British government saw the visit as the first step to healing the British and French political differences and indeed, it did lead to the Entente Cordiale that was signed in London on 8 April 1904.

Émile Loubet arrived on 6 July 1903, and his welcome in Dover was subject to special instructions from the Lord Chamberlain, Edward Hyde Villiers, 5th Earl of Clarendon (1846-1914). The President arrived from Boulogne at 13.15hrs on the 8,151-ton cruiser Guiche and even the weather obeyed the Lord Chamberlain’s wishes – it was superb! Prior to M. Loubet landing, members of the press from both France and England were entertained to lunch at the Burlington Hotel by Worsfold Mowll in the belief that this would ensure positive press coverage. The President disembarked on the Prince of Wales Pier where a Royal pavilion, specially brought from London for the occasion, had been erected and fitted out in the Louis XVI style. The President was met by Prince Arthur, Duke of Connaught (1850-1942), the French Ambassador to Great Britain (1898-1920) Paul Cambon (1843-1924), and staff from the French Embassy. Lord Howe – Lord-in-Waiting on behalf of the King, Captain the Hon. Seymour Fortesque – Equerry-in-Waiting and senior army personnel especially appointed by the King to escort the President throughout his visit.

The welcoming address was made in the pavilion by Dover Town Clerk – Wollaston Knocker. He then introduced the Mayor – Frederick Wright and Sir William Crundall who represented DHB. Members of the Corporation, the Dover Harbour Board, senior military personnel stationed in Dover and other local VIPs were in attendance. Following the welcome, the President and his entourage left in four Royal carriages, provided by the King, for Priory Station escorted by a detachment of 1st Royal Dragoons. The route was lined with soldiers from different battalions, boys from Dover College and Dover’s Gordon orphanage in their Scottish attire. Crowds, many from France, that had arrived earlier that day, cheered as the entourage passed. As the President entered the railway carriage on the train taking him to Victoria Station, London, a 21-gun salute was fired from the Western Heights. That evening and until the French President returned to his own country on 10 July, the government paid for Dover to be illuminated and as a goodwill gesture, DHB opened the Prince of Wales Pier to the public free of charge!

While the 500-foot landing jetty was being constructed on the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier, electrically powered capstans were installed. With the power coming from Dover electricity works through a newly laid cable carried within a cast-iron conduit that also powered the Wellington swing bridge when it was completed. Besides the covered landing stage and station, a wooden waiting room was erected close to the lighthouse. There, besides conveniences and telegraph facilities both light and alcoholic refreshments were available, for the latter the Lord Warden Hotel had gained a licence.

At the end of July 1903 the Hamburg-Amerika Line 4,550-ton Prinz Sigismund arrived to test the Prince of Wales Pier berthing facilities. On board was Albert Ballin, along with four senior officials and 700 passengers. The decked out ship, came alongside the Pier under the direction of the Harbour Master, Captain John Iron, without tug assistance. Herr Ballin was received by Sir William Crundall as Deputy Chairman of the Harbour Board, Councillor William Barnes the Deputy Mayor of Dover and Mr Phillips, representing British agents of the Hamburg-Amerika Line.

More than satisfied with the berthing and the proposed railway arrangements, Herr Ballin stated that the Line would make Dover the Port of Call for the English Channel the following year. On hearing the good news the Kaiser sent Crundall a telegram of congratulations. In the subsequent press statement, Crundall announced that besides the Hamburg-Amerika Line, the South America Line, Mexican Line and steamers bound for the Far East were making Dover a Port of Call. SECR estimated that on the agreement with the Hamburg-Amerika Line alone, 40,000 passengers a year would be using the Prince of Wales Pier. They therefore recommended an improved railway station and, reasoned, this would require the Pier to be widened. When it came to who would foot the bill, SECR said that they could possibly lend DHB the money which DHB would pay back out of the poll-tax revenue received from the ship passengers.

Dover Harbour Master, Captain John Iron (right) talking to Kaiser Wilhelm II on the König Albert 15.12.1903. David Iron Collection

On 15 December 1903, an agreement was signed between DHB, SECR and the Hamburg-Amerika Line for their ocean going cruise ships to call into Dover from 1 July 1904. On the morning of Sunday 13 March 1904 the Kaiser Wilhelm II, who was voyaging to Vigo and Gibraltar, was expected to arrive at the Prince of Wales Pier on the 10,643-ton König Albert steamship belonging to the Norddeutscher Lloyd Line. However, due to thick fog the ship was delayed so the Dover reception party travelled out on a DHB tug to meet the Kaiser in the Channel. The party included Captain John Iron, the Harbour Master, who was photographed talking to Wilhelm II on the Bridge.

Messrs Pearson and Son won the contract for the construction of the new steel swing bridge that replaced the existing Wellington Dock bridge and work started on 27 January 1904. At the same time began the construction of the 2,900-feet long branch line, with two steep gradients, from Harbour Station to the Prince of Wales Pier. On the Pier a covered railway station was built. The railway track followed the route agreed upon four years earlier, leaving the main line north of Harbour Station, going along Strond Street around the east and north of the Granville Dock to Union Street and then south across the Wellington Bridge and the Esplanade to the Prince of Wales Pier. In 1900 part of the grand Esplanade Hotel opposite the entrance to the Pier, had been demolished to widen the access from Union Street to the Pier for the new railway line.

At the Harbour Station, the down platform was rebuilt – on wheels – so it could be swung out of the way as needs necessitated! The new Wellington Bridge was completed in June 1904, and was swung by a combination of hydraulic and electric power, this project costing £600,000. On Saturday 25 June a trial run of a train onto the Prince of Wales Pier took place under the scrutiny of Major-General Charles Hutchinson (1826-1912), the former Chief Inspecting Officer for Railways. He was undertaking the commissioning tests of the Pier viaduct and the Wellington Bridge and was satisfied.

The Prinz Waldermar arrived on 1 July 1904 berthing alongside the designated transatlantic liners’ landing stage on the east side of the Pier. Following which, several Atlantic steamers called including the 16,550-tons Deutschland for which a special commemorative postcard was issued on her first arrival, 22 July 1904. SECR launched their new railway service – the Atlantic Liner Express. In December DHB’s new and powerful tug, the Lady Curzon, arrived as the primary tug for assisting transatlantic liners. However, at about the same time, the Admiralty issued an order stating that the Admiralty Harbour was only for the use by Royal Navy vessels. That all Commercial traffic was to moor in the Commercial harbour, contravention carried a £10 fine. This would be detrimental to the handling of transatlantic shipping so Crundall, Mowll and the town clerk – Wollaston Knocker, used all their persuasive power to convince the Admiralty to reconsider.

In March 1905, the large German steamer Erithia was being coaled alongside the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier when there was a sudden squall. The hundredweight (112 pound) coal bags were blown off the wagons and the horses bolted dragging the carts behind them. The squall quickly passed and the terrified horses were brought back. During the summer, ships belonging to the Red Star Line were regularly arriving at the Prince of Wales Pier and on 12 October, the newly launched 22,225 ton Amerika, built by Harland and Wolff, Belfast for the Hamburg-Amerika Line, tied up alongside the east side of the Pier. Local dignitaries headed by the Mayor/Deputy Chairman of DHB, Sir William Crundall, and crowds greeted her. The 25,128-tons Kaserin Victoria Auguste, built by Aktien-Gesellschaft Vulcan at Stettin (now Szcecin, Poland) for the Hamburg-Amerika Line on her maiden voyage, arrived on 11 May 1906. She was, at the time, the world’s largest liner and as she docked alongside the Prince of Wales Pier she too received a magnificent welcome.

However, the liners brought with them problems not previously considered. A seaman’s strike at Hamburg meant that the 8,332 ton Fürst Bismark, built in 1905 by Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company, Glasgow, left Hamburg with only half her compliment of crew. Bound for Mexico and Cuba, she picked up more crew en route for Dover where seamen had been recruited from London and Liverpool docks. On arrival at the Prince of Wales Pier, the British contingency realised that they were effectively strike breaking and rejoined the train that had brought them, putting their kit bags in the luggage van. Crew members of the Fürst Bismark took the kit bags off the train and on board the ship and trouble broke out. Although Dover spectators were in sympathy with the seamen, the officials were not and the police were called. Eventually, the men reluctantly went on board. However, as the ship was about to sail two British men climbed down the bow ropes onto the Pier and absconded. The next day the Deutschland, arrived with her full compliment of crew.

Work on building the Admiralty Harbour was still underway with the Southern Breakwater gradually narrowing the Western Entrance such that by the end of June 1906 it was only 1000-foot wide. The Deutschland arrived on Friday 13 July en route for New York coming in bow first and landing 93 passengers. At midday, 83 new passengers having embarked, the ship was leaving with the DHB tugs Lady Curzon and Lady Vita in attendance. The narrowness of the gap between the Southern Breakwater and the Admiralty Pier made the manoeuvre difficult and the transatlantic liner had to inch out. Owing to a mistake in one of the orders sent to the engine room, the Deutschland suddenly went ahead causing the tugs’ hawsers to snap. The order was then given to reverse engines and the ship hit the granite part of the Prince of Wales Pier extensively damaging her bows.

Much to the surprise of observers, the ship then majestically reversed out of the Western entrance without any assistance! While anchored in the Channel, arrangements were made for the Deutschland to return to port and that evening she again tied up alongside the Prince of Wales Pier. The 1,500 passengers on board disembarked and 1,200 sacks of mail for the United States were taken off. The passengers went by special train to Southampton where they boarded the New York, for America. Assessment of damage at that time showed that the bow plates of the Deutschland were doubled back to starboard and her fore compartments were full of water. It was decided that she would go to Hamburg for repairs where it was decided she needed 40 new bow plates.

Dover Harbour 14 July 1903 Prince of Wales Pier, to the right Admiralty Pier. Wellington Dock near the camara with Waterloo Crescent and Esplanade in between. Nick Catford

In the last six months of 1905 the number of liner passengers that embarked and disembarked on the Pier was 3,586 and for the corresponding period in 1906, 5,028 . However, a week after the Deutschland disaster the Hamburg-Amerika Company announced that the whole of their New York fleet would cease to call at Dover. An agreement was reached with the Admiralty that on the completion of the Admiralty Pier, DHB would be given the lease of the whole of the Pier in return for the Admiralty taking over the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier.

This was confirmed by an Act of Parliament that DHB sought. The same Act provided for the widening of part of the old portion of the Admiralty Pier bringing it, architecturally, into line with the rest of the Pier for the construction of what became the Marine Station. In the meantime a new transatlantic ships’ berth was erected on the Admiralty Pier extension that opened on 7 October 1908. By this time, the area of the Admiralty harbour was 610acres and the Commercial harbour 75acres. The Tidal Basin, Granville dock and Wellington dock amounted to 23acres giving Dover harbour a total of 708acres.

The Lord Warden, Lord Curzon of Kedleston (1859-1925), resigned in 1905 and was succeeded by Prince George the Prince of Wales – later George V (1910-1936). As Lord Warden, the Prince automatically held the office of Chairman of DHB but an Act of Parliament relieved him of the duty. This Act has been applicable to all subsequent Lord Wardens. The Deputy chairman of DHB at the time, Sir William Crundall, was elected Chairman of DHB and held the post until his death in 1934.

With a view to base part of the Home Fleet in Dover, the Admiralty started tests on the viability and in March 1907, undertook mooring trials. The 17,500-ton King Edward VII Class battleship, Africa narrowly avoided collision with the Southern Breakwater and the 12,790-ton armoured cruiser Duke of Edinburgh ran aground at high tide just off the Prince of Wales Pier. This was due to her anchor failing to find a purchase in the sandy seabed. Further tests showed that there were significant problems of pitching and rolling whenever the ships were expose to windy weather that were never solved. The results of the trials discouraged the Navy from considering establishing any great presence in Dover. Further, transatlantic liners were also experiencing problems and on 28 October 1907, the 12,760-ton Red Star liner Finland, homeward bound from New York to Antwerp, struck the end of the Southern Breakwater damaging both the ship and the Breakwater. She was brought alongside the Prince of Wales Pier where it was seen that her bows were extensively damaged. The Breakwater was also badly damaged and several workers were injured.

The new President of France (1906-1913) – Armand Fallières, (1841-1931), paid a State Visit on Monday 25 May 1908. Arriving on the 12,400-ton French armoured cruiser Léon Gambetta at the Prince of Wales Pier, a crimson-covered walkway was in position. He was escorted to the Royal pavilion, now kept in Dover for such occasions where Prince Arthur and other dignitaries received him. There were 60 war ships assembled in the harbour that day and troops from Dover, Shorncliffe and Canterbury garrisons lined the streets to Priory Station. Thousands of onlookers were on the seafront and along the route to watch the procession consisting of four carriages escorted by mounted 20th Hussars. At the station, members of the cast of the forthcoming Dover Pageant, dressed in full armour of Saxon and Norman knights with ancient swords and pikes, provided a spectacular guard of honour. It was agreed by the corporation to present the President with a silver salver engraved with emblemic views of Dover and in return the President presented the Mayor of Dover, Walter Emden, with the Chevalier Order of the Legion of Honour. The President stayed in Great Britain for four days departing from the Pier for Calais on 29 May.

Berthing trials were made by the 2,113-ton Royal Yacht Alexandra on 26 June 1908 at the Prince of Wales Pier and these proved successful. Edward VII, on 10 August, made the first crossing to the Continent on the Alexandra en route for Marienbad, now Mariánské Lázně in the Czech Republic, where he annually took the health waters. Subsequently, Royalty, particularly King Edward on diplomatic missions, frequently used the Pier.

After the Deutschland disaster, except for bad weather when cross Channel ships tied up there or the Alexandra was expected, it was assumed by national commentators that the Prince of Wales Pier would become a typical early 20th century promenade pier. In fact, they had forgotten that part of the role of the Commercial Harbour was that of a Harbour of Refuge. At the end of December 1906, the 4,158-ton steamer Ormley, from Belfast, went ashore at St Margaret’s Bay on Boxing Day (26 December). She was brought alongside the Prince of Wales Pier for repairs by the DHB tugs Lady Curzon and Lady Crundall. Although not the first shipping casualty to be tied up alongside the Pier, by the end of September 1908, seeing damaged ships there was a regular sight.

One evening, at the end of that month, the London collier steamer Southmoor, tied up alongside the Prince of Wales Pier with a number of boats in tow behind her. On board the Southmoor were women, many wearing the latest firs and fashion. In the boats were men, again, many were expensively dressed but like the women, were looking tired and crumpled. The 3,272-ton Argonaut, belonging to the Co-operative Cruising Company Limited, had been on her way from London to the Mediterranean with 120 passengers and the same number of crew on board. Off Dungeness, during thick fog, she had been hit by the 2,355-ton Newcastle steamer Kingswell with the Argonaut quickly taking on water. Her Captain called for the ship to be abandoned with the passengers and crew putting on warm clothes, life jackets and taking to the lifeboats. Twenty minutes after she had been hit the Argonaut foundered. The passengers were made up of members of British high society with one, the Countess de Hamil, losing her jewel case containing £6,000 of gems. The Southmoor took on board the women and the men, along with the crew members, were in the life boats that the Southmoor towed into Dover harbour.

A trial took place, on 1 October 1908, to disembark troops on the Prince of Wales Pier, with a view to use the pier for such military purposes. That day the 3rd Battalion the Worcesters’ arrived on the former Union-Castle requisitioned packet, by then a troop transport ship, Avondale Castle, from South Africa. On disembarkation the men were marched to the Dover garrison, where they were quartered. The exercise was reported as successful and in May the following year (1909) the Admiralty announced that a second landing stage was to be built on the east side of the Pier by a Gillingham firm. This landing stage was only 100-feet in length but had three decks connected by two stairways making it available for pinnaces and ships of all sizes at all states of the tide.

Prince of Wales later George V on 15 October 1909 on the Prince of Wales Pier following the official opening of the Admiralty Harbour. Dover Library

George Prince of Wales officially opened the Admiralty Harbour on Friday 15 October 1909. For the occasion, the Prince alighted from the train, that had brought him from London, by the Clock Tower from where he, and the entourage, were taken to the Eastern Arm. There the ceremony was performed following which he embarked on the yacht Enchantress and was brought to the Prince of Wales Pier. It was from the Pier station that the Prince boarded the train to take him to London. That day the flagship of Vice-Admiral Prince Louis of Battenburg (1854-1921), the 15,000-ton battleship Prince of Wales, was lying alongside the Pier.

In the spring of 1910 Edward VII was in Biarritz and on 27 April he returned to England. As was expected, arrangements were made for the Royal Yacht Alexandra to berth alongside the Prince of Wales Pier but a strong easterly wind was blowing and the Harbour Master, Captain John Iron, arranged for berthing on the west side of the Pier. This was not only out of the ordinary but not very convenient for the Guard of Honour, naval, military and civil dignitaries etc. Iron was ordered to arrange the Alexandra to come along the east side but he refused to comply and instead, arranged for a signal to be sent to the Alexandra saying that the yacht was to come in on the west side. Fearing that he had altered the King’s specific orders over the berthing arrangements, when Iron met His Majesty at the gangway he apologised for not obeying the Royal order. To this, the King responded, Why didn’t you?’ Iron replied, ‘Because I did not want her to be damaged by the swell setting on that side.’ ‘Ah,’ replied the King, ‘I knew you had a good reason.’ The weather, although very windy, was warm but Iron noted, that when they shook hands, how cold the King’s hand was. This was the last Channel crossing His Majesty made for on 6 May, King Edward VII died.

Although Edward VII only ruled for 10 years, during that time he made great use of his diplomatic skills. Thus, for the King’s funeral, special trains had to be laid on as more than 50 ruling monarchs, crown princes, special envoys and ambassadors passed through Dover. Typically, on 18 May 1910, a special train left from the Prince of Wales Pier at 15.10hrs carrying King Manuel II of Portugal and Alexander the Crown Prince of Serbia and both their entourage. Another train left at 17.20hrs with Prince Fushimi Sadanaru of Japan, Adolphus Frederick V – the Grand Duke of Mecklenburg-Strelitz and Prince Carl of Sweden and Norway, on board. The funeral was one of the largest gatherings of European Royals and many subsequently lost their thrones due to World War I (1914-1918). However, Manuel II of Portugal was deposed much earlier, in October that year.

To accommodate the new railway station on Admiralty Pier the bend in that Pier disappeared. During heavy weather the bend had provided shelter and the result was that there were numerous suspensions of Channel services or diverting of ships to Folkestone. To retain cross Channel shipping in Dover it was necessary to persuade the Admiralty to allow ships, during strong westerly winds, to tie up alongside the east side of the Prince of Wales Pier. On some days there were so many ships trying to get alongside the Pier that they were forced to tie up two abreast and delays were frequent. Military manoeuvres and the results of shipping accidents compounded the problem of shortage of space alongside the Pier at such times.

In the autumn of 1910, the twin-screw triple expansion engined 7,640-ton emigrant ship Cairnrona left London bound for New York. On board were approximately 900 passengers, mainly from Russia and Armenia. At about 05.30hrs on 3 September, 9-10 miles west of Beachy Head, fire broke out followed by an explosion and the ship turned back to Dover. Shortly after the accident, some women and children were transferred to the steamship Kanawha with the Upland taking on board a further 248 women and children. Those rescued on the Upland were the first to be brought to the Prince of Wales Pier and many of them were suffering from burns. This was the first that Harbour Master Iron knew of the accident and arrangements were quickly made to take the injured to the Royal Victoria Hospital in Dover.

At the time Vice-Admiral Prince Louis of Battenburg, was giving a dinner party on his flagship Prince of Wales alongside the Pier, and he ordered that all assistance was to be given by the Royal Navy ships berthed in the harbour. The Cainrona, later that night, was brought into to Dover by the Kanawha and DHB tugs. Many of the women and children rescued by the Kanawha were also in want of medical attention while on the Cairnrona, many of the crew and some of the 500 male passengers on board required medical attention and many more were seriously injured. The subsequent Inquiry found that the explosion was caused by red-hot ashes or cinders drawn from the furnaces that had found their way to the bottom of the starboard bunker. There they had come into contact with coal generated gas which in combination with air became an explosive mixture that was subsequently ignited. The explosion blew off the bunker hatches on the shelter deck. The Court found David Lowden, Chief Engineer, in default.

Mayor Edwin Farley greeting King George V and Queen Mary on the Prince of Wales Pier just before the outbreak of World War I. Clare Farley

Possibly because the Prince of Wales Pier was a hive of activity, it was popular for promenading. Possibly many of these spectators gave little thought to the full implication of the reasons as to why there was an increasing number of naval ships using the harbour. On 27 August 1911, Kaiser Wilhelm II had made his ‘Place in the Sun’ speech, which inaugurated the expansion of the German navy. From then on, the harbour was frequently visited by naval ships and a large number were present when, on 27 June 1913, Raymond Poincaré (1860-1934) President of France (1913-1920), departed for the Continent.

The President had been on a State Visit and his departure provided a great deal of interest for the onlookers, particularly because of the pageantry of the occasion. The Royal pavilion had been erected, the crimson carpet laid and the numerous British and French ships were dressed overall. Added to which the weather was fine and the Mayor of Dover, Edwin Farley, was presented with the Chevalier Order of the Legion of Honour. The highlight of the occasion occurred as the President’s ship, the Pas de Calais, passed through the Western entrance. Three Navy aeroplanes came from the direction of Eastchurch and flew over dipping their wings in salute. This was only four years after Louis Blériot had made the first heavier than air flight across the Channel!

The same atmosphere abounded on 21 April 1914, when the weather was summer like. Although folk were not allowed on the Prince of Wales Pier as King George V and Queen Mary was expected, the seafront was crowded. Boys from the Duke of York’s School provided the guard of honour on the Pier and as the train arrived in Priory Station at 10.20hrs. A salute of guns was fired and the ships in the harbour all sounded their horns. The Royal party arrived at the Prince of Wales Pier in an open carriage and as they boarded the Royal yacht Alexandra, the Royal Standard was broken out at the masthead. As soon as the Royal yacht left for France with escorting warships Nottingham and Birmingham, folk were allowed back on the Pier. From there they witnessed the arrival of the military airship B4 that landed eight passengers at the Castle. Four months later this world came to an end with the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918).

Part II of the Prince of Wales Pier story continues.

Presented: 23 September 2015