Aristotle (384 -322 BC), noted that ‘sunlight travelling through small openings between the leaves of a tree, the holes of a sieve, the openings wickerwork, and even interlaced fingers will create circular patches of light on the ground’ (Euclid Optics)

This is the principle of the camera obscura, a box with a hole in one side whereby the light from outside the box passes through the hole and reproduces an inverted image while the colour and perspective remains. In 1502, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) published the first clear description of the camera obscura in Codex Atlanticus and in 1725 Johann Heinrich Schultz (1687-1744) noted that silver salts would darken according the strength of light to which they were exposed. Dover diarist Thomas Pattenden (1748-1819) on 2 December 1797 mentioned that a Captain Thorley had loaned a camera obscura to him. Pattenden then took account of the measurements and bought a piece of glass to make a camera for himself. By that time artists were using the camera obscura to capture the image of their subject on a ground-glass screen.

Joseph Niczephore Niepce (1765- 1833), about 1826, found that when the image was thrown onto a pewter plate covered with a light sensitive coating of bitumen solution, after about eight hours the image became permanently fixed. Not long after Neipce went into partnership with Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre (1787- 1851) and adopting Schultz’s discovery, used copperplate covered with silver iodide as the light-sensitive coating. With this, in 1835, Daguerre succeeded in developing an image with mercury vapour. Two years later after more experiments Daguerre found that the image could be fixed permanently by immersing the plate in a solution of common salt. This became known as the Daguerre process and on the 9 September 1840 the Dover Chronicle reported that ‘Doctor Simon of Castle Street had produced a portrait from life by the Daguerreotype process.’ The article stated that the exposure was ‘taken under unfavourable circumstance. The sun having shone only eight minutes, seven more minutes were persevered in only a whitish light from a partly concealed sun … on to a silver oxide with mercury on a copper plate.‘

Dr J P Simon appears to have obtained a copy of Daguerre’s work for by Thursday 21 November 1839 having translated it he was selling copies for one shilling and sixpence each. Dr Simon was fluent of French and English and by that time had published a poem on photography and was giving lectures on the subject. The Dover Chronicle, acknowledging all of this said that Doctor Simon’s work should not be looked upon as a mere translation, but as ‘internal evidence of a practical knowledge of art.’ By 25 September 1841 Simon had obtained a Dagurreotype licence and produced ‘a portrait of a girl about ten years of age.’ He also continued to give lectures but these were only attended by a few and in May 1842 advertised his Dagurreotype licence and two years later advertised a series of farewell lectures prior to leaving Dover.

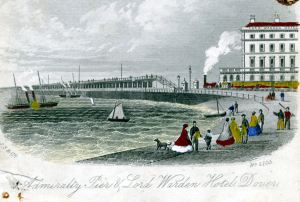

One of those who may have attended Dr Simon’s talks was Edward Sclater, born in Dover in 1803 he was, by 1840, was one of Dover’s foremost carvers and gilders. About that time Dover’s Town Clerk, Edward Knocker, asked Sclater to design and carve the former Lord Wardens shields. These can still be seen today decorating the Stone Hall of Dover’s Maison Dieu. It is not clear if Sclater bought Simon’s licence, but at about the same time as the doctor left Dover, Sclater added photography to his credentials. His workshop/studio was at 191 Snargate Street. Of interest, in 1828, Sclater’s daughter Ann, named after her mother, was born and when she grew up married Henry Crundall (1821-1894) from Lambeth, Surrey. His brother, William, became Dover’s Mayor and William’s son, also called William, was knighted and became Dover’s Mayor 13 times! Henry Crundall and Ann Sclater’s eldest daughter married John Iron (1858-1944), Dover’s long serving harbour master.

Dovorian George Thomas Amos, a devout Quaker, was born in 1827 and went to sea when he grew up. In the early 1850s he opened a tobacconist shop in Sandgate and about 1858, another one at 70 Biggin Street, Dover. It was here that Amos introduced photography into his business, at first using the Daguerreotype method. However, although this process produced positive exposures, each one was unique and could not be copied. William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) had looked at ways of copying exposures and in 1841, instead of glass plates tried using ordinary paper impregnated with silver iodide solution. When the paper was treated with chemicals a negative image became visible and each of these could be used to make a number of positives by shining a light through them and thus devised a method of making duplicates.

George Amos 70 Biggin Street December 1867 advert stating that his gallery is one of the largest in Europe

It would seem that Amos might have used the Fox Talbot’s process before switching to the wet-plate process that superseded it. This had been invented in 1850 by sculptor Frederick Scott Archer (1813–1857) who coated a glass plate with a liquid emulsion of silver iodide and photographic collodion, which he had invented. The process was quick, cheap and enabled portraits to be developed quickly and from this, the modern gelatine emulsion evolved. By 1867 George Amos, using this method, boasted in his adverts of the time to having one of the largest photographic galleries in Europe!

According to another of the Amos adverts, besides using the most modern equipment the sitters were placed ‘in the best possible position for the purpose of art and for taking portraits in all states of the atmosphere, as well as securing effect, which cannot possibly be obtained by any other gallery surrounded by buildings.’ Three years later, with the introduction of the Habitual Criminals Act, Amos won the contract to take photographs of criminals in Dover gaol for which he was paid 10 shillings each. Amos married Tabitha Manuel and had several children including Eugene, who joined his father in the photographic business. By this time he had moved to 12 Snargate Street. The developing of photographs was still a laborious skilled job requiring cumbersome equipment, but once Eugene learnt the trade, his father renamed the studio Amos & Amos.

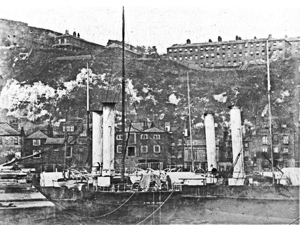

Eugene Amos quickly made a name for himself as a nautical photographer going out into the Channel, in all weathers, almost up to his death in 1942. During the inter-war period he photographed the salvaging of the Glatton that was sunk in the Harbour in 1918. Amos junior was also a eminent amateur archaeologist and recognising ancient finds in Dover as belonging to a Roman Classis Britannica Fort, he subsequently identified the location of a Roman Shore Fort. It would seem that Eugene Amos never married and by 1918, Amos & Amos was being run by Rachel Ann Amos. She died in 1920 but the business remained and seems to have been run by Eugene’s sister, Florence Mary Amos known as Flora, who had married Arthur Gregg in 1903. The studio/shop was bombed during World War II and never re-opened. Of interest Paul Amos, no relation, these days runs a photography business from the Old Print House in Russell Street.

In the 1850s the number of photographic studios in Dover started to proliferate. William Hayler had a studio in Snargate Street while nearby at 113 Snargate Street, drawing master Josiah Fedarb diversified into the photographic business. David Williams from Waltham opened a studio in Last Lane and M Barnett one at 166 Snargate Street. At 45 Snargate Street, Frederick Collins opened a studio and in 1859 William Wallis had a photographic business on Commercial Quay alongside Wellington Dock, but soon after moved to 36 Snargate Street then to Tontine Street, Folkestone. Canterbury born Samuel Jacobs opened his studio at 36 Snargate Street before moving to 2 Biggin Street. He was the Dover police photographer between 1872 and 1878 but in 1883 Jacobs moved to Sandgate. In July 1888, he committed suicide during a state of temporary insanity.

Edward King opened his business at 102 Snargate Street in 1862, moved to the Esplanade, on the seafront in 1874 and he too photographed criminals in Dover gaol. By 1862, Clark & Co opened up at 42, Townwall Street and James Clark opened a studio at 46 Snargate Street, staying for 7 years. Also in 1862, Thomas Wilkinson opened at 121 Snargate Street, staying until 1867 when the business passed into the hands of W M Newell who stayed until 1870. Meanwhile William Richard Waters opened his photographic studio at 7 Bench Street in 1867 and ran it for 5 years. Waters, the son of a Dover Pilot, was born in the Pier District of Dover and went on to become an eminent portrait painter whose studio was at 23 Castle Street. Eight of his paintings were exhibited at the Royal Academy and his watercolours of scenes in and around Dover received the recognition they deserved by the end of the 19th century. Why Water’s moved into the photographic profession is unclear for he was working as a successful artist from his studio and then his home at 15 Norman Street until days before his death on 4 January 1880.

From 1867 to 1901 Alexander James Grossman was listed as a Dover photographer. Born in Pressburg (now Bratislava), Hungary in 1834, Grossman was brought to England by his refugee parents while a child. Naturalized as a British Subject, he was christened at St Mary’s, Whitechapel, London in 1855 and joined the 95th Rifles renamed the Rifle Brigade in 1881. An early posting was to Dover where he met and married Sophia Ada at the Holy Trinity Church, in the Pier District. While in the army, Grossman was patronised by Prince Arthur (1850 -1942), during his service with the Rifle Brigade, whom, it was said, encouraged Grossman to become a professional photographer. Prince Arthur was the third son of Queen Victoria (1837-1901) and later became the Duke of Connaught giving his name to Connaught Hall and Connaught Park.

On discharge from the army, Grossman opened his photographic studio at Snargate House, 16 Snargate Street and was to stay there until 1901. From 1899, for two years, he also had a studio at 20 Biggin Street. In 1878, Grossman received international appreciation as an interpreter when on 26 November the 3,382ton Hamburg-American mail packet Pommerania, on a voyage from the US to Germany, was in collision with iron sailing ship Moel Eilion off the South Foreland. 172 passengers, mainly German, from the Pommerania were landed at Dover and taken to the Seamen’s Mission. There Grossman took on the mantle of interpreter and carer staying with the passengers until such time passage was found for all of them to return to Hamburg. After leaving Dover, Grossman retired to Holborn in the City of London.

About 1871 Richard Leach Maddox (1816-1902) invented the dry-plate process which meant that glass plates could be purchased with ready-coated dry emulsion of silver iodide and gelatine. This encouraged the growth of amateur photography by the wealthy which, in Dover deterred new photographers without alternative sources of income setting up a business. Some did try, for instance, Henry Verrall moved into 9 Bench Street in 1870, but does not appear to have stayed very long. James Walter Browning appears to have done considerably better, running a successful studio at 50 High Street from 1878-1890 when he sold the premises to Jean-Baptiste Gemneul Bonnaud. About the same time as Browning set up business Lambert Weston introduced photography into his artist’s studio at his home on the seafront.

Lambert Llewellyn Weston born on 25 September 1836 in Folkestone, came to Dover and became a successful artist. He owned 17 & 18 Waterloo Crescent with his studio in number 18, while number 17 was managed by his housekeeper who let it out to distinguished guests. During his career as an artist, Weston knew caricaturist George Cruikshank (1792-1878) who was a frequent guest. Another famous personage who rented Weston’s property was Charles Dickens (1812-1870). The great author was a frequent visitor to Dover and as he grew older spent an increasing amount of time, staying at Waterloo Crescent. It was recorded that Dickens, on fine days would walk up to Pilots Meadow, where he would work. The Times of 1 January 1896, tells us that Lambert Weston was an intimate friend of both Dickens and Cruikshank. In the early 1870s Weston opened a photographic studio at 18 Waterloo Crescent and it was to stay there for the next twenty years. Shortly after Weston opened another photographic studio at 23 Sandgate Road, Folkestone. By the time he died, on 2 February 1895, other members of Lambert’s family were running the photographic business and the firm, in Dover, moved to 15 Bench Street.

Frederick Artis, from Oxford moved into the former photographic studio of Thomas Wilkinson and W M Newell at 121 Snargate Street between 1881 -1883. Percy Pilcher opened his photographic business in Woolcomber Street in 1887 and then moved to 15 Castle Street staying there until 1892. About 1870, Martin Jacolette, born in Tavistock, Devon in 1850, the son of a Swiss miniature painter, came to Dover. Here he trained as a portrait painter and photographer under Lambert Weston and by 1881 had opened his own artist and photographic studio. This was in his home at 1 Priory Hill, although he remained with Lambert Weston managing the photographic side of his business.

By 1887 Jacolette had purchased, with possibly Weston’s help, North Brook House, 17 Biggin Street. The building had been the home of bootmaker Thomas Holloway having formerly been the home and possibly built for iron founder Edward Poole. According to local historian Joe Harman, the building foundations were strengthened by the use of old millstones, one of which came from Crabble corn mill. At the rear of the house, facing north, Jacolette built his photographic studio and subsequently earned a national and then international reputation as a portrait photographer.

As he climbed the ladder of success, Jacolette opened a studio at Queens Gate Hall, Harrington Road, South Kensington offering to undertake both portrait painting and photography. Nonetheless, it was his portrait photographs that received acclaim and in 1890 Jacolette introduced Photo-Mezzotint, which was soon adopted by portrait photographers throughout the country. However, on 3 December 1907 Jacolette died while undertaking a portrait commission in London, he was 56 years old. The following year an exhibition of Jacolette’s photographic portraits were shown at the offices of the British Journal of Photography, 24 Wellington Street, the Strand, London. Following Jacolette’s death North Brook House was sold as a going concern to Herbert & Reece photographers.

In the world of experimental photography attempts were being made to replace glass plates, usually 12 inches by 10 inches, with something lighter, more compact and in a form that would allow several photographs to be taken without reloading. George Eastman in the US manufactured the first successful emulsion-coated film in the form of a roll in 1889. Although the Eastman celluloid film had not reached the UK, the number of professional photographers and antiquarians in Dover, during the 1890s increased. It was noted in the local press that they were seen there in ‘droves’ in Cannon Street, during the demolition of the ancient houses prior to street widening for trams. The quaint interiors of these houses, some of them dating from about the time of the Commonwealth 1640-1660, were recorded, sadly most of the photographs, if not all, have been lost. However, when the buildings on the east side of Cannon Street, between St Mary’s Church and Market Square were demolished, unique views of the Church were photographed and some of these have survived.

In the Martin Jacolette stable and probably the one who took the photograph and tinted it was Thomas Moodie of Clairville, 40 Priory Hill. Moodie later set up as a photographic artist and miniature painter in his own right. Another artist/photographer was Reginald Millar of Maison Dieu Road while William Henry Pettitt was a reporter/photographer who, it would appear, freelanced for local papers. Pettitt was also the Dover agent of the Caligraph Typewriter, which boasted of the letters being laid out alphabetically with a level keyboard and having arithmetical and mathematical features.

At 129 Snargate Street Martin & Taylor opened their studio in 1890 staying there for nearly a decade. At 121 Snargate Street, what had been renamed the Snargate Street Studio was taken over by Frederick Deakin, who stayed until 1909. At 3 Townwall Street – on the south (sea) side of the then much narrower Street, William Henry Wright Broad (1851-1939) opened a studio in 1898. Born in Deal, Broad came to Dover as an assistant to Lambert Weston before opening his own studio. He stayed at 3 Townwall Street until 1909 and in 1900 was joined by Edmund Bowles who bought the studio and stayed until 1930. Broad lived at 5 Albert Road and died on 14 April 1939.

By the turn of the century, Dover was one of the most affluent towns in the country and this had a positive effect on the local photographic profession. Charles Stevens Harris (1865-1938) of Odo Lodge, 52 Odo Road, Buckland, opened a studio in his home about 1890 running it from there until 1899. Harris then moved the business to 77 London Road until he died on 13 October 1938 at the age of 73. In 1906 Harris produced a series of photographs one of which, a panoramic view of the Admiralty Harbour, was taken with a special camera and received national acclaim. The photograph features about forty vessels of the British Fleet sheltering in the harbour that was being built for them.

At about the same time as Charles Harris opened up his photographic studio, John George Whorwell opened his at his home, 7 Bench Street. This was the same address where William Richard Waters once had his photographic studio. Whorwell was a success as an out-of-doors photographer, specialising in outdoor shots of weddings and garden parties. Whorwell also offered dark room facilities for amateurs where he would teach his students how to use his equipment. Whorwell was also a local pioneer in producing moving pictures using the inventions of the time.

Having previously offering Lantern Shows based on the pioneering photographic studies of motion undertaken by Eadweard Muybridge (1830-1904), Whorwell was the first professional photographer in Dover to use a cine camera. William Friese-Green (1855-1921) had invented the basic feature of the cine camera and projector in 1888 and Thomas Alva Edison (1847-1931) had invented the kinescope in 1891. In France Auguste (1862-1954) and Louis Lumière (1864-1948) pioneered projection of the moving pictures and their first public performance took place in Paris on 22 March 1895. Using a combination of these inventions, Whorwell gave public shows.

Spanish ‘Flu’ epidemic 1918 – Postcard of a victim’s funeral procession by J G Whorwell, 7 Bench Street. Eveline Robinson collection

When John Whorwell died on 23 July 1933 aged 74, his son Arthur with the help of his sister, Lillian, took over the business. World War II (1939-1945) broke out in 1939 and just after midnight on Monday 4 October 1940, shelling destroyed the nearby Guildhall Vaults public house on the corner of Queen Street and Bench Street. Although the blast caused severe damage to properties in the area, the Whorwell’s studio quickly patched up their premises and returned to work. However, Arthur died on 15 March 1944 when Lillian subsequently took up the reigns. In September 1947 Lillian put on a successful child photography exhibition showing photographs taken by the studio from when it first opened. However, in 1971, the studio finally closed.

The number of photographers setting up business in Dover continued to increase. At his own home, Haslemere, Kearsney, George Hatton Buckman, the Chief Clerk at Dover Gas Company, had a studio. James Willis of 27 Buckland Avenue had a small studio and nearby at number 3 Buckland Avenue, John Harry Gibson also had studio – he specialised in outdoor photographs. B Knight briefly operated from 4 Snargate Street and then, it would appear sold the studio to George Lusty who came from Cheltenham. Herbert & Reece bought Jacolette’s studio at 17 Biggin Street and bookbinder, Tom Oakley had a studio at his home, Rose Cottage 32 St Radigunds Road. Thomas H Chapman opened a studio at 233 London Road in 1909, staying until the 1920s and in 1909 Edmund Vincer Bowles took over the studio at 3 Townwall Street.

Jean -Baptiste Bonnaud took over James Walter Browning’s studio at 50 High Street in 1895. Born in Limoges, France about 1839, Bonnaud retained his French nationality but hyphenated Barratt to his surname. He was a chemist and also had a business at Rue Louis 11a Ostend, Belgium. It would appear that Bonnaud had taken up photography as a sideline to running his chemist shop but by making full use of the new Eastman celluloid roll film had carved out a niche as a photographer of children. He stayed in Dover until about 1909 when he sold the business to George Jarrett.

George Henry Jarrett was born in Blean, near Canterbury, in 1881 and finished his training as a photographer under Jean-Baptiste Bonnaud. He bought Bonnaud’s business about 1909 and lived with his wife, Kate, above the shop. There his son, later Sir Clifford Jarrett the Chairman of Dover Harbour Board, was born in 1910 and daughter Joan was born 1914. George Jarrett was called up in World War I (1914-1918), leaving Kate to run the business with the help of Jarrett‘s assistant, later Mrs Ridgewell. However in the autumn of 1917 the shop was a victim of a bombing raid and Kate took their children to her parents home in Canterbury. Following the War, Jarrett returned and once the premises were made habitable, the family moved back in.

Mrs Ridgewell stayed with Jarrett until 1925 and later recounted to local historian Joe Harman, aspects of her job that mainly entailed re-touching prints. (My Dover p100-p101 published by Riverdale Publications 2001). ‘The work was done on the glass plate negative, using a very sharp black lead pencil which was sharpened by rubbing on emery paper.’ Her desk had side screens and a cover to cut out backlight and she held the negative paper over the aperture in the sloping board at the back. The natural light showed through and she could improve the negative. Head and shoulder portraits needed a lot of attention to remove some of the wrinkles and lines around the mouth for female sitters and frown on the men. The proofs were black and white but the finished prints were in sepia. Following the death of photographer, Charles Harris on 13 October 1938, Jarrett bought his studio at 77 London Road and stayed there until he retired in 1958.

Eastman Kodak Brownie box camera with fixed focus lens, single speed and a fixed aperture. Alan Sencicle

In the last days of peace before World War I, in 1911 Arthur Burger opened the Rapid Art Studio at 11 King Street and R Millar opened a studio in his home, 6 Bushy Ruff Cottages. That year the former Jacolette studio at 17 Biggin Street was transferred to Raymond Reece Lloyd who was still running it in 1917. In 1913, William Coppard and W Leppard opened a studio at 176 Snargate Street and were joined by Henry C Rhodes in 1915. In the US, George Eastman, who had produced the first celluloid roll film, also manufactured the Kodak camera, correctly advertised as ‘You press the button – we do the rest.’ It was a simple box with a fixed focus lens, single speed and a fixed aperture. In 1914 the company introduced the first precision miniature camera, the Minnograph, using 35mm film and was to be increasingly used in the War to come.

As World War I progressed a number of photographic studios opened and possibly included some run by men invalided out of the armed services. The studios included J Mackay at 7 Snargate Street and J F Bennett 38 Snargate Street. Walshams Ltd moved into the former Grossman studios at 16 Snargate Street and C Knight opened a studio at 35 Biggin Street in in 1915 and was also listed at 184 Snargate Street towards the end of the War. By 1919, M Seaman opened his Peoples Studio at 8 King Street, H Shaw at 61 Biggin Street and Albert Hayes opened a studio at 3 Frith Road.

Interior of the famous Martin Jacolette studio at the rear of North Brook House, 17 Biggin Street. Joe Harman

Following the War Dover, like the rest of the country, was hit by a deep economic depression that in turn led to fall off in the demand for the services of photographers. Further, existing photographic studios were under threat particularly from out of work military trained photographers setting up businesses. Many of these businesses were short lived but those that did survive for more than a year included, Bertram Hewson who joined H Shaw at 61 Biggin Street and Spencer Enterprises Ltd that set up at 74 London Road in 1922. S Wilson joined Sidney Charles Wallis who opened up a studio at 38 Snargate Street while Sydney Herbert Brock set up business in Maison Dieu Road in 1926 staying there until 1930 and Richard Levy opened up at 11c Bench Street. However, during the 1920s the former Jacolette studio became the Gas Showrooms and then changed hands many times but the once famous studio at the rear of the house, facing north remained. Following World War 2 (1939-1945) the building was gutted and rebuilt but the façade remained. In the 1990s it underwent another makeover and although the façade still remained the once famous studio was demolished. At the time of writing Halifax Bank occupy the premises.

The long established photographers were fairing far better with the Lambert Weston stable doing particularly well having an enviable proven track record in portrait photography. One of their photographers was Dorothy Sherwood who was born in 1889 into a middle class family with 7 servants at Sandgate Road, Folkestone. A keen amateur photographer, Sherwood trained with Lambert Weston’s Folkestone outlet and in about 1923 came to Dover to manage their smaller Bench Street studio. Whether it was Sherwood who took one of the most famous photographs of that time is unknown, but in 1922, the Lambert Weston studio was chosen to photograph Queen Mary (1867-1953), the wife of George V (1910-1936). The Royal personage was wearing the dress she wore at the last formal Court of the 1922 Social Season, this was sapphire blue and gold brocade embroidered in blue and gold diamante. Attached was an Irish lace train lined with gold tissue. The original black and white version of the photograph was published in the national and international press while a hand tinted coloured version was sent to British embassies, other official agencies and dignitaries throughout the World.

Much work had been carried out by a variety of researchers into the production of coloured photographs since James Clerk Maxwell (1831-1879), a British physicist had obtained a series of coloured negatives in 1861. To obtain these negatives, Maxwell had photographed tartan ribbon through three primary coloured filters and superimposed them to make full-colour photographs but was not very successful. In 1935, Eastman’s introduced Kodachrome film that consisted of three thin layers of emulsion, each sensitive to the different primary colours. When exposed, each retained an image of the scene in the colour in which it was sensitive. The film was developed layer by layer and a transparency was produced giving the true colours of the scene.

In 1931, Sherwood bought the Edmund Bowles studio at 3 Townwall Street and although she traded under her own name she sometimes did work for the Lambert Weston Company. Sherwood, by this time was one of the most famous portrait photographers of her time and turned 3 Townwall Street into one of the most celebrated photographic studios. In 1936, she married Henry Youden but continued to work as a professional photographer up to 1938 when she sold the business to Ray Warner. Dorothy Sherwood Youden died on 13 January 1958 age 70.

As Dover’s economy started to pick up, new photographic studios were established, these included W C Fuller at 78 Snargate Street and Farringdon & Harrison on Maison Dieu Road which later became R J Baker & Farringdon then Hudson Photo Service in Spencer Enterprises Ltd old studios at 74 London Road. Cuffs were a long established library and stationers at 1 New Bridge and following the War, Harcombe Cuff opened a photographic studio.

Harcombe Cuff devoted part of the premises to photographic equipment including selling Eastman’s Brownie Box cameras, Eastman Kodak films and Ilford films – the English equivalent. This encouraged amateur photographers in the area and eventually led to the founding of the Dover Camera Club, which met at the Art College, on Maison Dieu Road. There, youngsters and those who could not afford cameras were encouraged to join by making camera obscurers and to hand trace the vision displayed. Active members of the Club included Dover’s Town Clerk, Samuel Loxton, and the Charlton flourmill owner, Charles Chitty. Local historian, Joe Harman, was one of those who joined and went on to be an accredited amateur photographer.

Coast of France from Old Park published in the Times 09.05.1932 by Ilford Films using the new filter and Selochrome film

Ilford photographics founded in 1879 by Alfred Hugh Harman (1841-1913) as the Britannia Works Company in Ilford, northeast London. Initially they made photographic plates but became known for their celluloid roll films. By 1932, the company was a household name and in spring that year, they developed a revolutionary new ‘lens’ for cameras. This allowed the photographer to take long distance photographs that penetrated mist and haze. Based on the premise that red light scatters light less than blue, they developed an infrared filter – a suitably dyed piece of gelatine that was placed in front of a telescopic lens. To publicise the new ‘lens’ Ilford took photographs of Cap Gris Nez, on the French coast, from the roof of Old Park Mansion, Dover, in the presence of national newspaper reporters. On the day of the shoot, the unaided eye could not see the coast and to find direction a compass was used. The presentation was a success!

Just before World War II (1939-1945), Lowe & Son opened a studio at 148 Snargate Street which remained until they closed in 1962, having succumbed severe War damage. During the War, Dover became known as Hell Fire Corner and newspaper photographers frequently photographed the devastation. Following the War, in 1948, George W Tunnicliffe opened a studio at 127 Folkestone Road and in 1953 Fleet Street photographer and film cameraman Joe Court (died 2000) opened his shop and studio in the High Street. Court provided news photos and films for local and national media while his staff specialised in wedding photographs. The shop was run by Court’s wife Pat (died 2005), and in the early 1960s the business moved to King Street. At about that time photographer Ron Jones joined the staff and eventually became the manager staying until they closed at Easter 2005. Pat Court, was an active member of Dover Chamber of Commerce serving as its treasurer for a good number of years. She was also a founder member of the White Cliffs Tourism Association and helped to set up the Dover Cruise Welcome Club – now the Dover Greeters.

Shakespearian Play Coronation year – 1953, Kearsney Abbey probably taken by Ray Warner. Tom Robinson Collection

Ray Warner came to Dover in 1938, to manage the Bench Street branch of Lambert Weston and when Dorothy Sherwood retired bought her Townwall Street studio. Warner was born in Folkestone in 1914 and like Dorothy Sherwood before him, trained with the Lambert Weston company in Folkestone. During the War, Warner served in the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command as a photographer. Following the War, he returned to Dover with his wife Kay and rebuilt his neglected and war devastated photographic business premises. He also helped in the rebirth of the Dover Camera Club and was the chairman of the Dover Players, initiating the Shakespearian productions in Kearsney Abbey during the 1950s.

In 1961 Warner took over the Lambert Weston Company and changed its name to his own. However, at that time, the south side of Townwall Street was to be demolished to make way for a wider road to Eastern Docks and this included Warner’s studio. As his original premises were being demolished, Warner had a new modern studio built on the opposite side of the road that became number 42 Townwall Street. In 1977, Warner sold the business to commercial photographer John Caughlin who ran the company as Ray Warner Ltd. However, two years later, in 1979, the studio closed and Caughlin opened a business in his own name from his home in London Road, River. The Townwall Street premises were then used for an assortment of enterprises but in 2008, the block that housed the once internationally famous studio were bought by Dover District Council (DDC) and were subsequently demolished.

Although retired from the business, Warner continued to take photographs and filming films. In 1987 Raymond Baxter (1922-2006), the chairman of the Royal National Lifeboat Institution public relations, presented Warner with a silver statuette for 30 years service. For her Christmas cards in 1988 the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1978-2002) Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother (1900-2002) chose a photograph that Warner had taken of her at Walmer Castle. Sadly, a year later, on 15 December 1989 Ray Warner died and St Mary’s Church, Dover, was packed for his funeral but his legacy, the Dover Film Festival, lives on.

Film making had taken off since the turn of the century and in 1923 the earliest system for recording sound directly onto film was devised by US physicist Lee de Forest (1873-1961). This was introduced in newsreels in 1927 and employed in the first feature length ‘talkie’ in October that year – The Jazz Singer. Walt Disney (1901-1966), using the three-colour process in 1932, produced his cartoon Flowers and Trees and in 1935 the first Hollywood Technicolor film, Becky Sharp, was released.

In Dover, the Granville Film Society was formed in 1937 with founder members including Foley Gossling and Major Philip Walker. Gossling made a film for the occasion entitled Snow in the Channel, which was so successful that he was asked to make another. The project, Mr Probert, took a year and was shown just before World War II broke out. In 1948, Dover Film Society was formed and among the members were Gossling and Ray Warner. As a tribute to the Granville Film Society, they showed Mr Probert for ten days to packed audiences.

Opening of the Western Berth at the Camber, Eastern Docks 30.06.1953 by Minister of Transport Alan Lennox Boyd . Photograph by Ray Warner for Lambert Weston

Ray Warner had introduced film making into his photographic portfolio before the War and as a photographer in the RAF he had also made films. On reopening his photographic studio in Townwall Street in 1946, Warner started filming life in and around Dover, using professional 16millimetre film. The following year Warner showed a compilation of his films of local events and people and it was a massive hit! Over the next few years, Warner carried on making films on the life in Dover and occasionally put on shows that were always a success. In March 1953, to compliment the opening of the Eastern Docks as a major car ferry terminal, Warner, with port official W Taylor Allen, premiered their successful film, The Gateway of England.

Warner continued making film compilations of life in Dover and occasionally putting on shows, as these always proved popular, he decided to expand the idea into an actual Film Festival. Warner applied to Dover Borough Council for a grant and it was agreed that he would fund the film making side of the Festival and the Council would pay for the venue and its staging. The Film Festival was launched in 1971 – the 25th anniversary of Warner’s first compilation of Dover life. The Film Festival was booked to last three days and opened with a short film of general interest. This was followed by local historian, Ivan Green’s ‘Then and Now’ still slides of old Dover.

Photographer Ray Warner who founded the Dover Film Festival in the grounds of Kearsney Abbey. Dover Museum

An interval followed during which time the audience could browse an exhibition put together by Dover library and Dover museum. The audience then settled down for Warner’s compilation of Dover life. The format played to packed houses on each day and Ian Gill, the Town Clerk, encouraged Warner and Green to form a small committee and develop the idea. With publicity help from Councillor Peter Bean, the first Annual Film Festival was held in the Town Hall in 1972, however, in 1974 Dover District Council (DDC) took over from the Borough Council such that a new source of funding was required.

DDC agreed to fund the Festival for that year and sticking to the format, the three-day event was held in November 1974. Green gave an Illustrative talk on old Dover, Peter Belsey of Dover History Society and John Greenstreet together with Dover library put on a photographic exhibition and Reginald Adams gave a recital of music specially composed for the 1908 Dover Pageant. Warner’s photographic stills were on show and these included the ongoing work on the Channel Tunnel that included a shot of the mole boring machine breaking through the end of the pilot tunnel and another showing the depth of the borings.

In the compilation section there was a spectacular film of the gas works, on Coombe Valley Road, being blown up and of firemen fighting a blaze in the docks. There was also extracts of visits by the former Lord Warden (1941-1965) Sir Winston Churchill (1874-1965) as part of the celebration of his birth at the end of November that year. As a result of the successful Festival DDC agreed to annual funding as long as the Film Festival was expanded to cover the whole of the district with DDC also agreeing to pay for the Warner film print!

By 1983 the Festival was so popular that it was extended to four days and the following year, Warner’s annual film compilation of Dover life took on a highly professional look. This was with the help of sound recorder -Terry Nunn, film editor – John Falconer, scriptwriter -Terry Sutton and music composers and performers – Reginald Adams with Peter Stone. That year, 1984, the Film Society had won a £380 Kodak Community Award and with it involved many local groups and organisations in a project to make a film about Ralph Stott (1839-1877), who lived at Crabble House and produced an interesting flying machine. The story was written by and starred two reporters from the Dover Express, Don Lehane and Keith Murray, supported by a large cast including Peter Elgar, Betty Pilcher and Mandy Cork. The cameramen were Norman Williams and Harry Thomas, director Glyn Davies and producer, John Roy.

Ray Warner seat – a tribute to Dover’s photographer by the Rotary Club on the East side of the Seafront. LS

Ray Warner by 1989, had produced 41 annual films depicting the history of the changing face of Dover – a record hardly matched by any other town. That year his health started to deteriorate but with the help of Vice-Chairman, John Roy and the rest of the committee, the Festival was a success. However, Warner was a professional film maker and was determined, regardless that his health was failing, the 1990 festival should go on. Ray died in December 1989 and a seat presented by the Rotary Club in tribute to the great photographer can be seen on the Seafront. In the following March the Festival did go on and was a success.

Although everyone involved wanted to ensure that the Film Festival would go on, a number of problems faced the committee notably, none of them had been involved in direct film making, let alone were professionals. Further, not only was Ray Warner a professional who made films to extremely high standard, he never charged the Film Festival a fee. Another problem was that Warner, following the annual Festival, would tour clubs and organisations showing part of the annual film and promoting the next Festival, who would do that? Of equal concern was DDC who were putting considerable pressure on the committee and in particularly John Roy for a business plan over the future of the Festival. Then there was the problem of what would happen to the 42 films, including the 1990 film, that Ray Warner had made on Dover life plus his still photographs?

Roy and the Festival Committee came up with a workable business plan and professional photographer and film maker. Phil Heath, managing director of Heathfield Studios, Birchwood Rise, off Folkestone Road, Dover, agreed to take over the filming. In 1991, as of tradition, Phil joined John and Ivan along with Ivan‘s wife Margaret, all giving their services without payment. Margaret undertook the role of projectionist and co-researcher and Ray Warner’s films and photographs were cared for by Ivan and Phil. So successful was the Festival that the following year DDC agree to pay for the publication of the programme, the front cover of which became a collectors item in its own right! Sadly, not long after, John Roy died and the Festival was again put in jeopardy.

Luckily, the energetic businessman and tireless campaigner for Dover, Roy Dryden, came to the rescue and agreed to take over the role of chairman. Within two years of Dryden taking over, the number of performances at the Annual Festival increased to seven with an average of 400 people attending each day. 1996 saw the silver anniversary of the Festival, when Ivan and Margaret Green were presented with a silver salver. The following year the Festival broke all records with the number of people who attended and as on previous and subsequent occasions, the profits were donated to a local charity.

However, in order to meet the financial outlay of this increase in demand, more funding was required. Dryden and Heath applied for an increase in the grant from DDC for the 1995 production but they reacted by demanding editorial. The relationship turned sour and this resulted in a DDC officer making threats that were caught on camera. An internal investigation was undertaken and the council officers were cleared of maladministration but DDC did agree to carry out an audit of printing contracts. The subsequent Ombudsman’s report upheld DDC’s internal investigation saying that the allegations levied by Dryden and Heath were, with minor exceptions, baseless and that the coverage given by the local media was both misleading and sensationalised. Nonetheless, the Chief Executive of DDC was asked to apologise to Dryden and Heath.

Following the publication of the Ombudsman’s report, DDC’s Chairman at the time, emphatically stated that he was pleased that finally the matter could be put to rest. This, however, was not the case and Councillors demanded the resignation of Dryden and Heath. The result was opposite to what these Councillors expected, people who had not formerly attended the Film Festivals came to the 1996 one! Impressed with what they saw, they returned the following year with their friends and although money was desperately short, the 1997 broke all records for attendance with all five evening performances and both matinees packed!

Dryden, however, was more than a just a local businessman he was the President of the Dover Chamber of Commerce. Further, his battles on behalf of Dover, against DDC, for a better deal was, by that time, legendary and the Annual Film Festival became a target for retribution. The 1999 Film Festival was billed as the last but NOT through lack of public support. Ivan Green died in 2003 and the following year Ron Dryden died. The Ray Warner films were put into the safe custody of Jon Iveson, the curator of Dover Museum.

As a tribute to Ivan Green, in 2003, Dover Pageant Master Mike McFarnell showed a film depicting life in Dover during the previous year using the format that Ray Warner and Phil Health had used. Lasting an hour, the film was shown to an invited audience in the DDC Chambers, Whitfield. The event was hosted by the Chairman of DDC, Councillor Pat Heath and proved successful such that the Chairman encouraged McFarnell to revive the Annual Film Festival. McFarnell produced a business plan but estimated that cost would be £10,000 – more than he could afford. However, he said he would and did continue to film many aspects of the life of the town and district.

At the 2004 Dover Proms, Michael Foad presented McFarnell with a cheque for £100 to start a fund to buy a video projector and the Dover Carnival Association matched this. Joined by Terry Nunn to provide the narration and Terry Sutton, the script, McFarnell decided to put on a Festival in February 2005. His compilation of events in and around the district was shown in the Connaught Hall at the Maison Dieu, together with an earlier Ray Warner film. The Festival lasted two days with six showings each 61 minutes long on a screen paid for by Dover Rotary Club. Other contributions came from, Dover Daihatsu, Dover Kia, Dover Eurochange, Dover Harbour Board, Dover Town Centre Management, Friends of Dover Castle, George Hammond PLC, MWM Video production, Paul-Browns of Dover, P&O Ferries and SAGA Group Ltd.

The compilation included a whole range of aspects of Dover life from theatrical productions to sporting events, the annual inspection of Dover Sea Cadets on Remembrance Sunday to the annual Dover Patrol service at St James’ Cemetery with the ringing of the Zeebrugge Bell on the Maison Dieu balcony. Sir Richard Branson creating a new world record for the fastest Channel crossing was there and the atrocious weather that ruined the annual hospital fete and caused the flooding, not long after. The most poignant moment in the compilation was Dover stalwart, Jack Hewitt, filmed at the St George Day service at St Mary’s Church, shortly before he died.

The 2005 Film Festival was such a success that the Film Festival was returned to Dover’s social calendar. The 2006 and 2007 events were even more successful and in 2008 the Festival included a 20-minute workshop, given by Terry Sutton. Although the heating failed that year, the whole programme was a great success. 2008 saw the last Dover Pageant produced by McFarnell and in 2012, the Dover Pageant, as an organisation ceased. Up to then, while under the auspices of McFarnell, the Film Festival had been produced through the Dover Pageant Company. To enable the Film Festival to carry on, McFarnell set up a new ‘Not for profit‘ company limited by guarantee.

The 2011 film of Dover Life, presented at 2012 Dover Film Festival, the narration was by Terry Nunn and the script was written by Graham Tutthill. The film was sent to Dover’s twin town, Split, in Croatia for their international film festival. The Dover entry was in competition with nearly 300 tourism and travel related films from 69 different countries in the category for movies up to 60minutes long. 76 of these films were selected for showing and the Dover film won the top prize!

- Story First Published – Dover Mercury 24 January 2008

- Dover Film Festival: http://www.dover-film.com