Moray House, 103 Maison Dieu Road is now the presbytery for the adjacent St Paul’s Roman Catholic Church. In the early part of 20th century it was where the Lewin family lived and on 19 November 1920, where Terence Thornton Lewin (1920-1999) was born. He attended the Judd School, Tonbridge and on leaving school, Terence planned to join the police but as World War II (1939-1945), was imminent he joined the Royal Navy instead. As a naval officer, the young Terence was a gunnery officer aboard HMS Ashanti that helped bring relief to beleaguered Malta when about half the rescuing convoy were lost through enemy action. At the time this author’s father was on the island. According to him, if the Royal Navy had not made it through, Malta almost certainly would have capitulated. Mentioned three times in dispatches, Terence was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross and when peace returned he remained in the Royal Navy and rose through the ranks, from being the second commanding officer of the Royal Yacht Britannia in the 1950s, to First Sea Lord in 1977.

Knighted, Sir Terence was appointed Chief of Defence Staff (CDS) in 1979 – the most senior serving officer in the Armed Forces. Internationally, the Cold War (1947-1991) showed no signs of abating although there had been strategic arms reduction treaties. The USSR had deployed SS20 missiles at strategic places that were targeted at European cities and military bases. They had also invaded Afghanistan, in response to which US Pershing and Cruise missiles had been ordered by the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO). In Britain, Ministry of Defence, politicians and media attention centred on NATO and the Cold War. One of Sir Terence’s CDS predecessors was Lord Louis Mountbatten (1900-1979). When he held the post (1959-1965), his role had been that of an independent advisor to Government representing all three Services – the Army, Royal Navy and Royal Air Force. Since then the role had evolved to that of chairman of the three Armed Services who, in turn were supported by government Junior Ministers for each of the services.

Although the seven met regularly, approximately every six months they would meet to review colonial theatres of operation throughout the world and contingency plans if potential problems were identified. In June 1981, the Junior Ministers’ roles were scrapped and the role of the CDS returned to the Mountbatten model. Thus the prime responsibility of the CDS was that of giving a ‘neutral’ opinion to the Government as the leading adviser on the Armed Services. The individual Chief of Staffs of the three Services retained their previous rights including personal access to the then Prime Minister (1979-1990), Mrs Margaret Thatcher (1925-2013). Although superficially it appeared that these changes strengthened the senior personnel of the Armed Services, in fact it was part of a Government initiative to weaken them in order to play one off against the other and reduce defence spending.

In January 1981, John Nott was appointed Secretary of State for Defence (1981-1983). Nott was the author of the 1981 Defence White Paper, The Way Forward. This proposed extensive cuts to the Royal Navy that included sale of the aircraft carrier Invincible, selling 9 of the 59 escort ships and withdrawal of Endurance, the ice patrol ship in the South Atlantic. Additionally, the possible sale of Intrepid and Fearless, disbanding the Royal Marine Amphibious Force, closure of Chatham Dockyard and a cut of 8,000 to 10,000 naval staff. There were to be cuts in the regular Army that would be offset by the expansion of the volunteer Territorial Army. Cuts to the Royal Air Force were to be minimal, focussing on what was seen as out of date such as the long-range Vulcan bomber but increasing the number of aircraft needed for Britain’s role in the Cold War. This did not altogether sit well with Sir Terence, particularly in relation to the Royal Navy, therefore he used his new position to fight the cut backs.

There had been a dispute since the mid 19th century with Argentina over British control of the Falkland Islands in the South Atlantic, which the Argentinians called Islas Malvinas, along with South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Britain colonised the Falklands in 1833 whereas Argentina, the eighth largest country in the World, was formed out of the Spanish Viceroyalty of the Rio Plata and achieved her independence in 1861. In early 1982, the population of the Falklands was 1,800 mainly made up of former British nationals. At the time Argentina was ruled by a military junta of three under the Presidency of General Leopoldo Galtieri (1926-2003). The other two members were Admiral Jorge Anaya (1926-2008) Commander-in-Chief of the Argentinian Naval Operations and Brigadier Basilio Arturo Ignacio Lami Dozo the Commander-in-Chief of the Argentinian Air Force. This junta was unpopular and was facing major economic problems. Therefore a diversion was called for.

Admiral Anaya firmly believed that the Falklands/Malvinas belonged to Argentina. He put forward a well-argued treatise suggesting the time was ripe for Argentine to retake them. In Admiral Anaya’s opinion, the British Foreign Secretary (1979-1982) Lord Peter Carrington was known to favour decolonisation of British territories. Although when the British Labour Party were in power, they had seen off an Argentinian attempt at repossession. It had already been muted by the Conservative government that in order to withdraw Britain’s involvement in the South Atlantic, Argentina would be given the islands with a certain, but easily ignored, caveat.

The caveat he was referring to was in order to protect the Islanders sovereignty, the British proposed to lease them back for a limited period of time. Albeit, Anaya reasoned, in recent legislation on British nationality the Falkland Islanders had not been given any special status. Further, the recent British Defence Review had made it clear that the Royal Navy was to be severely reduced and this included scrapping of the only British naval vessel in the region, the Endurance on 15 April that year. Looking at the wider picture, the US, as far as Argentina was concerned, required the country’s anti-Communist allegiance in South America and also as a trading partner. The United Nations (UN) would be averse to military action by the British so even if they opposed Argentina’s repossession, Anaya reasoned, this would merely be a token response. Therefore Argentina had nothing to lose so Galtieri was persuaded.

Sir Terence was in his final year as CDS before retirement. A British joint services expedition were finishing a remapping survey of South Georgia, 800 miles east of the Falkland Islands. Like the Falkland Islanders, the tiny population on South Georgia depended on fishing and sheep farming. As Sir Terence was a patron of the expedition he was given a copy of the map, which he took with him to New Zealand the following month. On 19 March 1982, a group of 40 Argentinian civilians, under scrap metal dealer, Constantino Davidoff, arrived on South Georgia having been given permission by the British Embassy in Buenos Aires, Argentina. They had proposed to dismantle an old whaling station on the island and sell the metal for scrap. However, on arrival on the island, Davidoff ran up the Argentinian flag.

At the time Endurance, under the command of Captain Nick Barker (died 1997), was in Stanley, the capital of the Falkland Islands on East Falkland. With 24 Marines on board from Naval Party 8901, based on the Island at Moody Brook Barracks south east of Stanley, Endurance set sail for South Georgia to investigate. They arrived at Grytviken on 24 March where some of the Marines set up an observation post. Davidoff and his men were dismantling the old whaling station, nonetheless Endurance, with the remaining Marines on board, stayed in the area.

On that day, Sir Terence and Mrs Thatcher went to Northwood, Hertfordshire. In 1938 Northwood had opened as the headquarters of the Royal Air Force Coastal Command. A network of underground bunkers and operation blocks was then established on the site. When the post of the Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet was created in 1971 the Royal Navy took over the site and later the headquarters of the Flag Officer of Submarines moved to Northwood in 1978. There, on the 24 March visit, the Prime Minister met the Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, Admiral Sir John Fieldhouse (1922-1998) and his staff at their underground command post.

It was believed that the Argentinian navy were strung out along the country’s coast patrolling its 200-mile zone some 1,000 miles away from the Falklands. When asked by the media if the visit by the Prime Minister was to discuss a British Task Force landing in South Georgia, this was denied. However, Argentinian intelligence sources stated that the BBC news had reported that a task force was about to be deployed to the South Atlantic. In Buenos Aires the Argentinian strategy was discussed in the light of the BBC report and the invasion brought forward.

Friday 26 March and British intelligence reported that 2 Argentine corvettes were sailing towards South Georgia. Foreign Secretary Carrington was having increasingly chilly diplomatic discussions with General Galtiari and three days later, on Monday 29 March, intelligence reported a well equipped Argentinian fleet were two days sailing distance from the Falklands. On the same day Sir Rex Hunt (1926-2012), the Governor, Commander-in-Chief and Vice Admiral of the Falkland Islands received a communiqué warning that an Argentinian submarine was off the Islands, probably reconnoitring for good beachheads.

US Secretary of State, Alexander Haig (1924-2010) was in contact with Lord Carrington and pressured the British Government not to undertake any enforcement action as he was seeking a peaceful solution. From then on Secretary of State Haig travelled between Washington, Buenos Aires and London conducting what was termed shuttle diplomacy to gain peace. In London, at one of many government meetings on Wednesday 31 March, it was said that the general feeling in Cabinet, Parliament and the media was that to recapture the Islands, if they were invaded, was foolhardy.

At the time Sir Terence was in New Zealand watching military exercises but was in contact with Mrs Thatcher and also Sir Henry Leach (1923-2011), the First Sea Lord. Sir Terence advised, in the first instance, the early retaking of South Georgia as a contribution to a graduated pressure on the Argentinians’ as well as a useful exercise of the Tri-Service co-operation between the British three armed services. If the Argentinians did not pull back, sending in a Task Force to retake the Islands if need necessitated. This, in Sir Terence’s opinion, would lead to a loss of ships but the Task force would achieve its objective.

Sir Terence’s rational was reiterated in detail by the First Sea Lord at a meeting in Downing Street, but was against the advice of the Ministry of Defence which Defence Secretary, John Nott, put forward in detail. However, Defence Minister Nott did make it clear that, in his opinion, if the Argentinians invaded the first British submarines to arrive should launch an early attack. This, he went on to say, should be followed by the declaration of an Exclusion Zone by the British government and then the Argentinians would go away. The meeting lasted some 5hours at the end of which Mrs Thatcher asked Sir Henry Leach what he thought should be done. His response was to follow Sir Terence’s advice and to form a Task Force with the authority to send it. Both the submarine Spartan, under Commander James Taylor and Splendid, under the command of Roger Lane-Nott were ordered to prepare and be on standby. In the early hours of Thursday morning, following another very long meeting chaired by Mrs Thatcher, Hermes and Invincible aircraft carriers, were also put on standby.

On 1 April, Sir Terence arrived back in England and was told that in accordance with his advice, the remaining Marines on Endurance disembarked with the order to put up a token resistance if the Argentinians landed. Deploying at the British Antarctic Survey base, King Edward Point, on South Georgia, the Marines prepared for a possible invasion. The first Argentinian forces to arrive opened fire and the Marines fought back managing to bring down a helicopter that was about to land more troops. An Argentinian corvette opened fired from the sea but the Marines succeeded in causing sufficient damage below the vessel’s waterline that it withdrew. However, within three hours the eighty Marines were surrounded and having fulfilled their remit including killing five Argentinian soldiers and injuring seventeen, surrendered. They were taken to Montevideo the capital city of Uruguay and a few days later were repatriated to Britain. Coming in for severe criticism from politicians, Sir Terence held his nerve and continued to push for the retaking of South Georgia as soon as practically possible.

At 04.40hours the following day, 2 April, 150 men of the Argentinian Special Forces unit, Buzos Tacticos, landed by helicopter at Mullet Creek inlet, on the east coast of East Falkland. There they split into two groups; one headed for the Royal Marines Barracks at Moody Brook and the other to Port Stanley. Due to the events on South Georgia, the commanding officer at Moody Brook, Major Mike Norman, had relocated his headquarters to the Governors’ House at Port Stanley. The Islands’ only protection was a number of manned defence positions around the East Island. Major Norman had arrived with his detachment a few days before in order to relieve Major Gary Noott and what should have been an outgoing 8901 detachment. The two Royal Marine forces combined and Major Norman took command, as he was the senior of the two Officers.

When the Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher was informed of the invasion, instead of suggesting a token offence and the diplomatic handover of the Falklands to Argentina, she took the advice of Sir Terence. The Overseas and Defence, South Atlantic Committee better, known as the War Cabinet was set up comprising key Cabinet politicians including, Home Secretary (1979-1983) William Whitelaw (1918-1999), John Nott, Lord Carrington and Sir Terence. The media quickly latched on to the fact that the Chancellor of the Exchequer (1979-1983) Sir Geoffrey Howe (1929-2015) was not included. Mrs Thatcher said he had been left out, as she wanted to keep money out of any decisions made. The War Cabinet met at least once a day and sometimes meetings lasted many hours. According to Sir Terence’s biographer, Rear Admiral Richard Hill (Cassell 2000), he and Mrs Thatcher, ‘… really clicked, once they learned to trust each other.’

Named Operation Corporate, the British offensive was under the control of Commander-in-Chief of the Fleet, Admiral Fieldhouse using his headquarters at Northwood. The Operation consisted of two separate seagoing Task Forces, one consisting of surface ships, called the Fleet Task Force, and the other nuclear-powered submarines and both supported by air defences. An Amphibious Task Force, if the Argentinians did not back off, would undertake the landings of the Land Force Task Group that would retake the Falklands. Again they would be supported by air defences. The Land Task Force Group would also receive support from the Fleet Task Force until they retook the Islands. Finally, but an intrinsic part of the plan from the beginning, would be the Special Forces (UKSF) operations. The whole operation would be Tri-Service made up of the British three armed services.

Although, on paper this seemed an audacious if excellent plan, in reality there were a number of major logistical problems. The main one was the distance between the UK and the Falklands. A convoy of ships were selected and made ready. Submarines already at sea set course for the South Atlantic. However, the only British C-130 aircraft capable of landing at Stanley airport were not fitted with air-to-air fuelling probes (AAR) and without the support of air defences, retaking of the Islands would be impossible. So a strategy plan was worked backwards from June 1982.

The South Atlantic in June would be in the depths of winter and although on a similar latitude to Britain, the Islands did not have the benefit of the Gulf Stream or equivalent, to warm the seas. In the northern hemisphere’s summer months icebergs frequently came within 200 miles of the Falklands. The Islands do not have high mountains or continental land masses to protect them, in consequence the average wind speed is 15 miles per hour against in Britain where it is on average, 4 miles an hour. As the Task Force ships chosen would be in operation until at least June, by that time they would badly be in need of a full refit. Therefore, in order for Sir Terence to mount a major offensive to demonstrate the capabilities of the Tri-Service, the Operation had start before 1 May. The three Services Chiefs, agreed with Sir Terence, that it could be done.

Brigadier General Mario Benjamin Menéndez (1930-2015) the Military Governor of the Malvinas, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands.

Meanwhile, at 06.15hours on Friday 2 April the first force of the Argentinian Buzos Tacticos attacked the Governor’s residence on East Falkland. Major Norman was there and shortly after, one of his defence positions at Yorke Point reported that Argentinian forces were landing at Yorke Bay, 4 miles north-east of Stanley and close to Stanley airport. This followed by a report that amphibious armoured personnel carriers were advancing on Port Stanley. As these troops headed towards the Capital they were met by a section of Royal Marines and two vehicles were knocked out. The section then made their way to Government House, which some 600 Argentinian troops had surrounded and fierce fighting took place. Following the capture of the Falklands Broadcasting Station and the Cable and Wireless Office in Port Stanley, which stopped any outside communication, Rex Hunt took the decision to surrender to the Argentinians. This took place at 09.25hours when the Royal Marines were ordered to lay down their arms. The Governor and Marines were flown to Montevideo and from there to Britain. General Galtiari appointed Brigadier General Mario Benjamin Menéndez (1930-2015) the Military Governor of the Malvinas, South Georgia and South Sandwich Islands.

That day, two of the Submarine Task Force, Spartan and Splendid were already sailing towards the South Atlantic. A third submarine, Conqueror, under the command of Captain Christopher Wreford-Brown, was ordered to join them. Before leaving Faslane Naval Base on the Clyde, where Conqueror was being prepared, a team of UKSF joined the crew. The UKSF men had with them knives, hand guns, rifles, heavy machine guns, hand grenades, limpet mines, plastic explosives, Gemini inflatables, outboard motors and skis, all of which were stowed alongside the submarine’s torpedoes! Conqueror set sail for the South Atlantic on 4 April and Captain Wreford-Brown’s basic remit was the finding and attacking any Argentine naval forces threatening the Task Force.

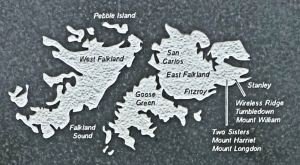

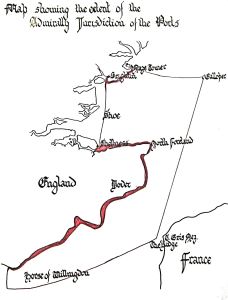

The route of the British Task Force to the Falkland Islands and South Georgia 1982. National Memorial Arboretum Staffordshire

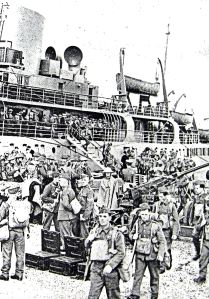

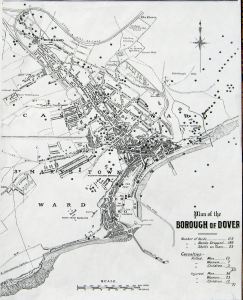

Number 3 Parachute Regiment (3 PARA) was at its base in Tidworth on the Salisbury Plain when they received the order to stand-by. On 4 April the Commanding Officer, Lieutenant Colonel Hew Pike, met with Brigadier Julian Thompson, the Commander of 3 Royal Marine Commando Brigade of which 3 PARA would be a part to bring the Brigade up to strength. During the next five days all preparations were made and the on 9 April the Brigade set sail on the requisitioned P&O cruise liner Canberra from Southampton. Lieutenant Colonel Herbert Jones (1940-1982) was the commanding officer of 2 Parachute Regiment (2 PARA) and was on holiday abroad with his family when the crisis came. The Regiment was in Aldershot at the time, routinely preparing for a six-month tour of duty in Belize, Central America. Most of his force had been stood down the previous weekend for Rest and Recuperation. Jones immediately returned to Aldershot and with great determination informed all the relevant parties that his battalion was to be part of the Task Force. This was followed by recalling all of 2 PARA troops by telegrams, ‘phone calls and notices at railway stations and ports including Dover.

While these preparations were going on the Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington, through Sir Anthony Parsons (1922-1996) – UK’s Permanent Secretary at the UN, tabled the motion demanding the immediate cessation of hostilities and a withdrawal of Argentinian forces from the Falkland Islands. This was sanctioned as Resolution 502 with the call by the UN Security Council for a diplomatic solution to the situation and for both countries to refrain from further military action. Adopted by 10 votes to 1, with Panama opposing and the Soviet Union, Spain, Poland and China abstaining. The mandate was given the full support of the Commonwealth and the European Economic Community. This gave more power to the US Secretary of State, Alexander Haig for a compromise. On 5 April Lord Carrington resigned, taking the full responsibility for the complacency and failures in the Foreign and Commonwealth Office to foresee the development of the Falkland crisis. Francis Pym (1922-2008) was appointed in Lord Carrington’s place and was more in tune with Sir Terence’s stance on Operation Corporate.

Mrs Thatcher, meanwhile, was building up a close relationship with the President of the US, (1981-1989), Ronald Reagan (1911-2004), who had previously referred to the Falkland Islands as a ‘little ice cold bunch of land.’ She was well aware that Britain depended on US Sidewinder missiles to arm the Harriers as well as intelligence and diplomatic support to retake the Falklands. Apparently, she told the President that the fundamental principal of what the free world stood for was at stake and that if Britain gave way, then these principles would be permanently under threat. Thereafter the President and the Prime Minister became close allies. However, Haig was not so inclined and saw the only answer was in a peace settlement in compliance with the UN Resolution 502.

The Fleet Task Force, consisted of 115 ships with the aircraft carriers Hermes and Invincible setting sail from Portsmouth on 5 April. In 1966, Sir Terence was the Captain of Hermes and his second in command, at that time, was John Fieldhouse! On board the Hermes was Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward (1932-2013), the Commander of the Fleet Task Force at Operation Level. As the two ships left, Sir Terence was in consultation with Sir Michael Havers (1923-1992) the Attorney General (1979-1987) – a former Recorder of Dover (1962 to 1968), as well as officials and legal advisers from the Cabinet Office, the Ministry of Defence and the Foreign and Commonwealth Office. From these discussions Sir Terence drew up Rules of Engagement that could be used and activated on ministerial authority. To these the Prime Minister added that the commanding officer would naturally have the right to exercise his discretion on any matter relating to the safety of his vessel.

It was agreed that a forward logistics base was to be set up at Ascension Island some 4,250 miles south of the UK and 4000 miles north of the Falklands. From there, RAF C-130s and VC-10s could deliver supplies from the UK and supplies could be air-dropped from helicopters to the Task Force. Although Wideawake airfield on Ascension had a 10,000-foot runway it had been leased by government to the US and Pan American Airways managed it. At the time, the airfield was only used about four times a week for which Pan American Airways maintained more than adequate fuel capacity but this was not sufficient for heavy use. To make the airfield viable, a tanker was moored off the Island to pump fuel through a floating pipeline to the bulk fuel farm at Georgetown, the Capital on Ascension. From there the RAF laid a pipeline to the airfield. A fleet of tankers that were fed by fourteen commercial tankers supplied the fuel for the Task Force.

In order to give more time for a diplomatic withdrawal, on 7 April, the War Cabinet agreed to a 200-mile Maritime Exclusion Zone (MEZ) that would come into effect at midnight on 11/12 April. The following day Defence Secretary Nott announced to the House of Commons that from the time indicated, ‘any Argentinian warships and Argentinian auxiliaries found within this zone will be treated as hostile and are liable to attack by British forces.’ He went on to say that the measure was ‘without prejudice to the right of the United Kingdom to take whatever additional measures may be needed to exercise the right of self defence, under Article 51 of the United Nations Charter.’ Argentina, the other South American states and the Soviet Union were warned to keep their submarines out of the Exclusion Zone.

On arrival at the Exclusion Zone the Submarine Task Force were briefed to conduct surveillance of Argentine forces and collect intelligence about naval movements. They were permitted to use minimal force in self-defence and if the Argentinian forces attacked Endurance, they were to return sufficient fire to prevent further attack. Spartan arrived in the Exclusion Zone on 12 April and went to undertake reconnaissance off Stanley. On 15 April they observed two Argentinian vessels laying two minefields near the entrance of the harbour. The submarine stayed in the area until 21 April providing updates on activities. Splendid arrived in the Exclusion Zone on 15 April, positioned north west of the Islands. In accordance with the directive, the crew gathered and forwarded intelligence to Northwood. In between, like the crew of Spartan, they trained for attack and counter attack. Conqueror was sailing towards South Georgia as part of Operation Paraquat – the reoccupation of that Island. On arrival on 18 April, the UKSF men on board were transferred onto South Georgia but during the transfer two of them slipped. A full load of equipment was washed off Conqueror’s casing by the rough weather but was recovered by a helicopter.

Wideawake airfield on Ascension Island became one of the busiest airports in the World on 16 April with over 300 aircraft movements. RAF Harrier jump jets and Royal Navy Sea Harriers were flown in having been fitted with AAR’s and thereby were refuelled en-route and during operations. Also fitted with AAR’s were the long-ranged Vulcan bombers, which had been saved from being scrapped! They were used in the operations and particularly the attack on Stanley airfield and its defences. Also arriving on Ascension were Nimrods to carry out maritime surveillance sorties and patrols in support of the Fleet Task Force as it sailed south. Hercules transport aircraft carried supplies to Ascension before being deployed to support the Fleet Task Force as it approached the Falklands.

Ships belonging to the Amphibious Task Force started arriving at Ascension Island on 17 April and one of the first was Fearless the headquarters ship of the Amphibious Task Force. Also senior personnel of the Land Force Task Group. Hermes was in port and on the same day Admiral Fieldhouse with Air Marshal Sir John Curtiss (1924-2013) and Major General Jeremy Moore (1928-2007) flew in. Air Marshal Curtiss was the Task Force Air Commander whose headquarters was at Northwood and had an excellent rapport with Admiral Fieldhouse.

Major General Moore was a former Housemaster at the Royal Marines School of Music, Deal and in Command there between 1973 and 1975. From 1979 he was in Command of all the Marine commando forces and was on the verge of retirement. Having taken part in the strategic planning at Northwood, he flew to Ascension to take over the Land Force Task Group. This consisted of the 3rd Commando Brigade that included the 2 and 3 PARA, and the 5th Infantry Brigade. A Council of War was held on Hermes to discuss landings and the repossession of the Islands. It was assessed that there were approximately 10,000 Argentinian troops on the Islands of which about 7,500 were in the Stanley area and therefore there was a need for more troops and ships.

At a War Cabinet meeting on 21 April Sir Terence informed Mrs Thatcher that an Argentinian naval force had been located, including the aircraft carrier Veinticinco de Mayo – the former Royal Navy ship Venerable. She was between the Argentinian coast and the MEZ and that Splendid had been ordered to observe. The War Cabinet recognised that the British submarine would be under the high seas ‘Rules of Engagement’ so she could not attack except in self-defence. That afternoon, in Buenos Aires, US Secretary of State Haig met with President Galtieri. The President told him that he was planning a visit to the Falkland Islands and that he was prepared to withdraw his troops from the Islands if Britain recognised Argentinian claim to sovereignty with no concessions.

News of the meeting and the outcome reached Downing Street at 21.00hrs and an hour later Prime Minister Thatcher met with William Whitelaw, Francis Pym, John Nott, Sir Terence and Cecil Parkinson (1931-2016). The latter was there in his capacity as the Conservative Party Chairman to explain to Mrs Thatcher the ramifications within the Party of conclusions made. The meeting lasted two hours following which Francis Pym flew first to Brussels to meet with European Ministers then to Washington. His brief was that concessions, demanded by General Galtieri, could not be made as the British Parliament or the country would not accept them. At the same time, Splendid was ordered to return to the MEZ. Both the diplomatic visits and the return of Splendid was in order that Britain would NOT be seen impeding the negotiations that had been implemented by the United Nations Resolution 502 and carried out by Haig.

Due to not wanting to be seen to be going against the UN Resolution 502 and upsetting Haig’s peace negotiations, pressure was put on Sir Terence to stop Operation Paraquat – the retaking of South Georgia. The US Secretary of State Haig, for his part, informed Galtiari on the impending possibility of British forces trying to retake the Island. In documents of the time, Haig said that he was doing this to show Galtieri that the US was neutral and could be trusted in the negotiations. It was agreed with Mrs Thatcher that if Operation Paraquat failed then Sir Terence would take the full blame. Sir Terence’s nerve held and on 25 April he was able to telephoned the Prime Minister from Northwood to say that members of the Royal Navy, Marines and Special Forces had retaken the Argentinian base at Grytviken on South Georgia with relative little loss of life! After making the announcement to the Commons, Mrs Thatcher and the War Council cabinet members went to Chequers, the official country house of the Prime Minister near Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire. There, in a meeting lasting four hours they were briefed in detail by Sir Terence. After the meeting Mrs Thatcher had an audience with the Queen that lasted a further two hours. The other members of the Cabinet were briefed at Northwood.

Four container ships were requisitioned and converted into aircraft transporters in order to take supplies to the Fleet Task Force. They were the 14,950ton Cunard roll-on roll-off Atlantic Conveyor, her sister ship, Atlantic Causeway, the 18,000tons Contender Bezant and the 28,000tons Astronomer. At the time the arming of requisitioned none-military ships was controversial so not one of the requisitioned ships had any form of defence. The Atlantic Conveyor left for Ascension on 25 April with a cargo of six Royal Navy Wessex helicopters and five RAF Chinook helicopters. At Ascension her cargo was increased with the addition of six of the nine RAF Harrier jump jets and the eight Royal Navy Sea Harriers. The other three ships were loaded with supplies.

By this time the Fleet Task Force under Rear Admiral Sandy Woodward aboard Hermes were nearing the MEZ and on 29 April Splendid detected five Argentinian frigates. These were the Argentinian escort forces and were soon joined by more vessels including destroyers and the Veinticinco de Mayo. In London, Sir Terence told the War Cabinet that the Veinticinco de Mayo aircraft carrier was capable of covering 500 miles a day and therefore could be a military threat from any position and concluded that a submarine attack to disable the Veinticinco de Mayo was the best option.

After discussing the legal, political and military implications of such action, the War Cabinet authorised an attack on the aircraft carrier. To tighten up the justification the MEZ was redefined as a Total Exclusion Zone (TEZ) and included air defences. On 30 April the Argentinians were informed that, ‘Any ship and any aircraft, whether military or civil, which is found within the zone without the due authority from the Ministry of Defence in London will be regarded as operating in support of the illegal occupation and will therefore be regarded as hostile.’ Copies were sent to the US and Secretary Haig, other South American countries and the Soviet Union.

On 29 April Conqueror received orders from London to locate the General Belgrano group and headed towards the possible location. The General Belgrano or Belgrano as she was generally referred to, was formerly the USS Phoenix that had survived the attack on Pearl Harbour and went on to see action during World War II (1939-1945). She was armed with 15×6-inch guns with a range of 13 miles and 2 British Sea Cat missile systems. Two Exocet-armed destroyers accompanied the cruiser. The following day Rear Admiral Woodward was given permission to enter the TEZ and to start the process of recapturing the Falkland Islands. As a form of protection, Conqueror was given permission to attack but only ships within the TEZ.

The Conqueror on 1 May, located the Belgrano and her escorts but this was outside the TEZ. That day a number of British ships in the Fleet Task Force had been subject to air attacks and Vice Admiral Woodward was of the belief that that a full-scale attack was developing. It was known that although Stanley Airport was inadequate for the Argentinian Mirages and Skyhawks, moderate improvements would make the airfield feasible. Therefore, that day Vulcans and Sea Harriers attacked the airfield putting it out of immediate operational use.

That evening the Argentinian Operational Commander, Rear Admiral Jorge Allara, on the orders of the Argentinian Commander of Naval Operations in the South Atlantic, Vice Admiral Juan Jose Lombardo, prepared for an all out attack. The aircraft carrier Veinticinco de Mayo and her escorts were to go north of the TEZ, from where they were to launch an air attack at first light. A second Argentinian task force, which included Exocet missile-armed frigates, was to deploy south of the TEZ in order to attack any British warships that attempted to flee the Veinticinco de Mayo attack. Finally, a third task force, which included the Belgrano, were ordered to the Burdwood Bank – an area of shallow water approximately 120 miles south of the Falklands in which submarines find it difficult to shadow – and to deal with any British vessels operating in that area.

On receiving this intelligence, Vice Admiral Woodward became increasingly concerned that the Fleet Task Force was in danger from a ‘pincer’ attack. In his report the Vice Admiral stated that he saw this coming from the three separate Argentinian contingents: the aircraft carrier Veinticinco de Mayo with escorts to the north of his position; Exocet missile-armed frigates in the centre and to the south the gun-armed cruiser, the Belgrano, accompanied by the two Exocet-armed destroyers. ‘My hope was,’ the Vice Admiral stated, ‘to keep Conqueror in close touch with the Belgrano group to the south and to shadow the carrier and her escorts to the north with one of the submarines up there. Upon word from London, I would expect to make our presence felt, preferably by removing the carrier, and almost as important that aircraft she carried, from the Argentinian Order of Battle.’ (HMS Conqueror – Report of Proceedings 01.07.1982)

In the early hours of 2 May, Vice Admiral Lombardo issued the order for Rear Admiral Allara and the Argentinian units to close on the British Fleet Task Force and attack without restriction. The communiqué was picked up by British intelligence and duly forwarded. It confirmed Vice Admiral Woodward’s belief that the Belgrano and her escorts, who were heading south, would use the darkness to turn and steam towards the Task Force. When near enough to strike, he believed, they would again change direction in order to launch an attack while ships in the Task Force were preparing to receive a missile attack from another direction. Vice Admiral Woodward wrote ‘I badly need the Conqueror to sink her (the Belgrano) before she turns away from her present course, because if we wait for her to enter the TEZ, we may lose her, very quickly.’ (Sandy Woodward – One Hundred Days, Harper Press 2012).

Vice Admiral Woodward was authorised to take action against any Argentinian forces he thought were threatening him but was not able to command the submarines to help without going through the War Cabinet. Further, neither contingent could attack unless they were within the TEZ and both Task Forces were outside the TEZ. At the time, both Splendid and Spartan were looking for the Veinticinco de Mayo Group and were unable to make contact. However, Conqueror had picked up the sound of the Belgrano Group and on 1 May had made visual contact. For the next twenty-four hours the submarine shadowed the Belgrano Group and on 2 May Conqueror reported to Northwood that the Group had changed course towards the Fleet Task Force.

As Vice Admiral Woodward’s worse fears grew he signalled London ordering that Conqueror sink the Belgrano. In London, the message was blocked to stop Conqueror acting on the command and passed on to Sir Terence. This was 10.45hours 2 May and Sir Terence called a meeting of the Chiefs of Staff who, with the news of Vice Admiral Lombardo’s orders to attack, agreed that the standing Rules of Engagement be altered to permit a counter attack by Conqueror. At the time Mrs Thatcher was at Chequers, with the War Cabinet politicians and Sir Terence went straight there. They were already aware of Vice Admiral Lombardo’s orders and when Sir Terence explained the situation, they agreed to his request to change the Rules of Engagement. The politicians main concern was that it would be political suicide if they did not acquiesce to Sir Terence’s request and the Belgrano sank the British aircraft carrier with hundreds of casualties. Permission was granted for Commander Christopher Wreford-Brown, the Commanding Officer of Conqueror to attack the Belgrano if she posed a threat to the British fleet. The Ministry of Defence sent a signal to this effect at 12.07hours and within half-an-hour, new orders were issued.

Conqueror was 36 nautical miles (58 kilometres) outside the TEZ, at torpedo depth. On board she had two different types of torpedoes, World War II Mark8 type, which were reliable, accurate at close range and had a warhead capable of penetrating the hull of the Belgrano. The second type of torpedoes was the more modern Mark24 Tigerfish, which had a tendency to be unreliable. On consultation with his officers, Wreford-Brown ordered three Mark8s be to be made ready. The weather was stormy and closing in. The Belgrano was gently zigzagging at about 13knots and it was important not to betray Conqueror’s position. The atmosphere on the submarine intensified as she came closer to the Belgrano. At 18.51hours the Belgrano was down to a speed of 11knots and the three torpedoes were put into standby mode. At 18.57hours the Conqueror was 1,400-yards on the Belgrano’s port beam when Commandeer Chris Wreford-Brown ordered the three torpedoes to be fired at three-second intervals. The first torpedo missed the Belgrano and hit one of the escort vessels but did not explode for a further 57seconds. The second hit the Belgrano, mid-ships and exploded on impact. The third also exploded when it hit the stern of the Argentinian ship.

In total, 321 men lost their lives and 15 minutes after the Belgrano’s crew was ordered to abandon ship, she sank. Setting a course to the south, Wreford-Brown ordered the Conqueror to go to a depth of 500-feet and a speed of 22knots. The two escorting Argentinian destroyers went after the Conqueror, and one depth charge exploded close enough to make the 4,000-ton submarine shudder. Nonetheless, she managed to clear the area with the destroyers returning to rescuing the 700 men in life rafts from the cold, open ocean. Controversy followed as it was stated by a number of countries that although international law stated that in times of war, the heading of a belligerent ship had no baring on its status, the Falklands Conflict was not technically a war. Second, the Belgrano was outside the British imposed TEZ. Further, and the lasting aspect of the controversy, were intercepted Argentinian signals that ordered their fleet to return to the previous positions as they had been spotted by a Royal Navy Sea Harrier. This could mean that the Belgrano was sailing away from the Fleet Task Force. However, increasing evidence at the time showed that they were not received in London until after the Conqueror had attacked the Belgrano.

Nonetheless, when the crew of Conqueror returned to their homeland, they and their families were hounded mercilessly by the press. The Prime Minister, Mrs Thatcher came in for a well publicised grilling on BBC’s Nationwide, (24.05.1983), by schoolteacher Diana Gould (1926-2011) from Cirencester, Gloucester. Mrs Gould accused the Prime Minister of ordering the sinking of the Belgrano in order to de-rail the US Secretary of State Haig backed Peruvian Peace Plan. Of the controversy, Sir Terence said, ‘A catastrophe like the sinking of a major unit was bound to happen sooner or later once the Argentinians had invaded and the Task Force sailed. They must have realised the risk, we certainly did, and it was my job to ensure that it didn’t happen to us first.’

Meanwhile, both Spartan and Splendid were still looking for the Veinticinco de Mayo Group but to no avail. Following the attack, the aircraft carrier along with the Argentinian Naval Force, was returning to Argentine territorial waters. The Veinticinco de May was located outside the territorial waters but the decision of the War Cabinet was to do nothing unless she changed direction with a clear hostile intent. Internationally, the US Secretary of State Haig was threatening Britain with political isolation if the Peruvian Peace Proposals were not accepted. On 6 May the Rules of Engagement were changed to include the restriction of attacks on the Veinticinco de Mayo when she was more than twelve hours steaming distance from the Task Force.

Two days after the sinking of the Belgrano, on 4 May, an Argentinian Exocet missile hit the British destroyer Sheffield launched by Queen Elizabeth II in 1972. It was fired at 11.04hours approximately 20-30 miles away from a Super Étendard fighter, piloted by Lieutenant Armando Mayora and Lieutenant Commander Augusto Bedacarratz, who was commanding the mission. The aircraft came from the Rio Grand air base, Tierra del Fuego, flying below the Task Force’s radar screens. Captain James William Salt (1940-2009) only had time to shout ‘Take cover!’ Before the missile struck Sheffield amidships about 8-feet above the waterline. The result was an inferno killing 20 and severely injuring 24 of the crew. Fire crews from other ships fought the raging fire but as she was being towed to South Georgia Sheffield sank. The site is now a designated War Grave. Sheffield was the first loss of a major British warship in 37 years.

The requisitioned P&O cruise liner Uganda had been designated a hospital ship and fitted out accordingly. On board were 12 doctors, 40 members of the Queen Alexandra Royal Naval Nursing Service and medical support staff. The survey vessels Hecla, Hydra and Herald had all been fitted out as ambulance ships and they took the dead and wounded to Uganda. During the remainder of the Conflict Uganda and the converted survey vessels along with Argentinian ambulance vessels dealt with both British and Argentinian casualties. The staff on board Uganda undertaking a total of 504 surgical operations and treating 730 casualties. Both British and Argentinian casualties were transferred to Montevideo from where they were returned to their home countries.

As a gesture of solidarity on 5 May, Prime Minister of New Zealand, Robert Muldoon, told Sir Terence that his country would loan their Leander class frigate Canterbury, if Britain launched an attack. She was strictly to be used to relieve a British ship from other duties in order for it to go to join the Fleet Task Force. The gesture was accepted but opposition to the Conflict increased in the UK with many commentators supporting Leader of the Labour Party Michael Foot’s (1913-2010) argument for the US backed compromise. While others were quick to side with one of the editors of the Labour Herald, Ken Livingstone, who wrote that the Government had ‘blood on its hands from the senseless war.’

Meanwhile, on 7 May, Sir Terence, in a press conference, stated that he saw the way forward was through negotiation. That the build up of diplomatic, economic and military pressure was bringing about an achievement. Foreign Secretary Pym, in the House of Commons, reiterated this line of argument. However, in the subsequent press conference, Pym lost his temper with a journalist saying, ‘You may be on the Argentinian side but I must tell you that we are certainly not asking anything too much of the Argentines. They invaded, they are the aggressor. They put their forces onto that island and, when Resolution 502 was passed, they used it to reinforce that island.’ Resolution 502 had been adopted by the UN Security Council on 3 April and had called for a diplomatic end to hostilities between Britain and Argentina over the Falkland Islands.

Albeit, within Britain, the general mood was of support of defending against an invasion and with this the number of vessels and military forces the War Council sent to the area increased. In the US President Reagan openly expressed support of the British stance but his opposition and some members of his administration, particularly Secretary of State Haig, wanted a settlement saying that the Conflict was causing an unwanted distraction to the Administration’s diplomatic relations with South America. On 7 May, the Land Force Task Group under Major Jeremy Moore, left Ascension Island to retake the Falkland Islands.

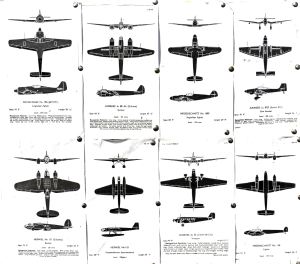

Intelligence had informed Northwood that the Argentinians had set up an airbase on Pebble Island, part of the Falkland Islands group, north of West Falkland. The island was/is almost two islands joined by an isthmus, about 19 miles by 4.3 miles at its widest point with a sheep and cattle farming settlement and a bird reserve. Using a local airstrip, the Argentinians named their airbase Aeródromo Auxiliar Calderón, or Calderon as it was referred to by the British, and based some 300 Argentinian airmen protected by a small unit from their Naval infantry battalion. Also at Calderon were T-34 Mentors and Pucara aircraft and a newly erected radar site that could be used to attack the proposed landings on the Falklands.

On the night of 13/14 May an eight-man section from the Boat Troop of DD Squadron Special Air Services (SAS) landed on Pebble Island and set up two observation posts. They carried out surveillance of the settlement, the radar site and the airfield. On the night of 14/15 May, Sea King helicopters landed 45 men of D Squadron accompanied by naval gunfire forward observer, Captain Chris Brown and supported by gunfire from the destroyer Glamorgan directed by Captain Brown. The SAS men destroyed 11 aircraft, the radar, an ammunition dump and an aviation fuel store. One was hurt and, according to British intelligence, the Argentinian Commanding Officer of the Base was killed.

Following the success of the Pebble Island raid, it was agreed to mount a similar raid on the Rio Grand air base, Tierra del Fuego, South American mainland. The airbase housed the Exocet missiles and the Super Etandard bombers that would carry them. Code-named Operation Mikardo it was to be undertaken by 55 SAS men and reconnaissance for the Operation began in the early hours of 18 May from Invincible. A Sea King helicopter was used to fly the eight men reconnaissance group and it was planned to drop them on the Argentinian side of Tierra del Fuego and for the helicopter then to go to Chile, as it would be at the end of its operational range where it would be destroyed. Unfortunately, the helicopter was forced to divert, adding twenty minutes to the journey, then as the mainland was approached thick fog cause delays that led the operation to be aborted.

Commodore Michael Clapp commanded the Amphibious Landing Force on the Falklands. His job was to select a suitable landing area and deliver the troops ashore safely. He selected San Carlos Water, a fjord-like inlet on the west coast of East Falkland facing Falkland Sound. This is the sea strait between the two main islands that included at least eight safe anchorages. Reconnaissance showed that there did not appear to be Argentinian troops in the immediate area and to protect the landing force from air attack, Sea Harriers would provide air cover. However, of concern was an Argentine position at the top of Fanning Head, at the north end of Falkland Sound, which was armed with heavy weapons.

East Falkland Island – the day augured well when the Task Force started to arrive at San Carlos Bay. Alan Sencicle

On being given permission by the War Cabinet the British Fleet entered San Carlos Water during the night of 20/21 May quietly sailing past the Fanning Head position. Under the command of Major-General Moore at 02.30hours local time on 21 May the British troops and supplies started landing on three beaches inside San Carlos Water. The day augured well as there was low cloud, which with the total blackout of information, it was hoped, would reduced the chance of an air attack. However, later that day the Task Force was spotted by the Argentinians at the Fanning Head position and at approximately 17.40hours local time the bulk of the air strikes began.

The bombing was heavy and tended to be aimed at Royal Navy frigates and destroyers not the supply and troops ships. The Royal Navy frigate Ardent, whilst lying in Falkland Sound, was attacked by at least three waves of Argentine aircraft and sunk leaving 22 dead. Thirteen bombs hit the ships of the Task Force without detonating including a 1,000lb that hit the destroyer Antrim whilst supporting the main landing. Two days later, 23 May, the frigate Antelope was on air defence duty at the entrance to San Carlos Water protecting the beachhead established two days before. She came under attack from four Skyhawks but although damaged she was moved to sheltered waters. There were two unexploded bombs on board that needed to be dealt with and one of which was in a dangerous state. The Royal Engineers bomb disposal technicians came on board but on the fourth attempt at defusing the bomb it exploded killing one of the bomb disposal team and badly injuring another. Antelope was forced to be abandoned and within minutes of the crew leaving, the missile magazines began exploding.

On 25 May the destroyer Coventry along with Broadsword were about 10 miles north of Pebble Island acting as decoys to draw Argentinian aircraft away from San Carlos Water. The attacking force moved in and three bombs struck Coventry just above the waterline, two of which exploded. One entered the Forward Engine Room causing the ship to list to port. The other breached the bulkhead causing uncontrollable flooding. Within 20 minutes Coventry was abandoned and capsized. Nineteen of her crew were lost and a further thirty injured with one dying from his injuries later. Famously, while the crew were waiting for Broadsword to come to the rescue, they sang Monty Python’s Eric Idle comedy song ‘Always Look on the Bright Side of Life,’ that featured in the 1979 Python film Life of Brian. Sir Terence had an emotional attachment to Coventry as his wife Jane had named her at the launching. He argued that the announcement of the ship’s loss was not to be made until he had a full list of the casualties and the relatives had been informed. However, Sir Terence was over-ruled by John Nott.

Sir Terence had an audience with the Queen on 25 May, to brief the Monarch on the San Carlos landings. That night the Atlantic Conveyor was due into San Carlos Water. She had left Ascension Island in a convoy that included the requisitioned Queen Elizabeth 2. Included on board the Atlantic Conveyor was equipment for the construction of an airstrip at San Carlos and the five Chinook and six Wessex helicopters. The helicopters were to be used to move 2 PARA and 3 PARA to key high grounds and were urgently needed. On arrival one of the Chinooks left the Atlantic Conveyor on a mission. Shortly after and before the ship had been unloaded, Exocet missiles hit her with the loss of twelve crew members and the urgent supplies. In the light of the Atlantic Conveyor attack the much larger and better known Queen Elizabeth 2 that was bringing 3,000 members of the Fifth Infantry Brigade, was diverted to South Georgia. For the journey she was blacked out and with her radars switched off, steamed without modern aids to avoid detection.

Some 3,000 British forces, most belonging to 2 PARA and 3 PARA had quickly secured the beachhead at San Carlos. With the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor and the Chinooks they faced a long march across East Falkland to Stanley 50 miles away. The loss of the ships and subsequent delays were taking its toll back in the UK, where the demand for the withdrawal from the Islands was mounting. Internationally, pressure was being put on the UN to call for a cease fire. About thirteen miles to the south, through rough and boggy terrain, much of it heavily mined,was/is the Darwin settlement. This is on the east side of the central isthmus of East Falkland and about 2½ miles away is the settlement of Goose Green.

About 1,200 Argentinian troops occupied both Darwin and Goose Green and in Goose Green village hall over 100 islanders were imprisoned. Although, it had been planned to bypass Darwin and Goose Green, the War Cabinet wanted an early offensive as a distraction. Sir Terence and Admiral Fieldhouse in discussion with Major-General Moore chose to take on the Argentinian troops at Darwin/Goose Green. If successful, it would boost moral in the UK and the forces would be in control of a significant portion of the East Falklands.

Brigadier Julian Thompson, the Commander of 3 Royal Marine Commando Brigade of which, by this time both 2 PARA and 3 PARA were part, had set up his headquarters at the commandeered Camilla Creek House. This was between San Carlos and Goose Green and the Battle for Darwin and Goose Green started when Colonel H Jones of 2 PARA was ordered there. 2 PARA were to ‘carry out a raid on Goose Green Isthmus and to capture settlements before withdrawing in a reserve for the main thrust to the north.’ Air support was to be provided by RAF Harriers and naval gunfire support was to be provided by the frigate Arrow during the hours of darkness. Due to the loss of the Atlantic Conveyor with the helicopters that were to move 2 PARA, the company had walked, undetected, through the rough terrain to Darwin. Further, the BBC World Service had informed its listeners that a parachute battalion was preparing for an attack on Darwin and Goose Green!

Against a determined stand by the Argentine 12th Infantry Regiment, ‘A’, ‘C’, and ‘E’ company of 2 PARA fought hard but were failing to make much headway and were stuck at the bottom of Darwin Hill. Above them were Argentinians in well-defended trenches. Colonel H Jones initially led an unsuccessful charge and then turned west along the base of the Hill. Again he tried to advance up the hill and was just short of the trenches when he was hit and fell. Colonel H Jones got up was hit again twice, fell back and died. He was posthumously awarded the Victoria Cross.

Goose Green Village Hall where locals were imprisoned when the Argentine Military Junta took over the Islands in 1982. Alan Sencicle

Major Chris Keeble took over PARA 2 on the death of Colonel Jones and it was about noon on 28 May when the trench was cleared and sometime after Darwin Hill was secured. While this was going on a second and equally as fierce fighting was taking place to secure Boca Hill by 2 PARA’s ‘B’ Company under Major John Crosland. With ‘A’ company staying at Darwin Hill, ‘B’ made their way south to Goose Green and ‘C’ and ‘D’ companies made their way to Darwin school and the airfield. The fighting remained fierce and by the last light on 28 May the situation was not brilliant. Although casualties were being evacuated, the remaining men were exhausted, their clothes were wet and it was bitterly cold. They had surrounded both Darwin and Goose Green but the Argentinians were still putting up fierce resistance. Major Keeble spoke to the company commanders and suggested that the Argentineans be asked to surrender but to make the period of negotiations as long as possible to give time for reinforcements to arrived! If they refused, the Officers suggested, then Goose Green could be flattened with artillery and mortars and then attacked. However, there were civilians locked in the village hall.

With Brigadier Thompson’s agreement, Major Keeble, Captain Alan Coulson and Captain Rod Bell, the latter of which translated it into Spanish, worked on a surrender text. At 10.00hours on 29 May, two Argentinian prisoners, who had been well briefed, were sent into Goose Green. If they were not back within I hour, the prisoners were to say, then Goose Green would be flattened. Within minutes the two men returned and a meeting took place between Major Keeble and his contingent who met with Air Vice-Commodore Wilson Dosio Pedroza and Lieutenant Colonel Italio Pioggi (1935-2012) and his contingent that took place in a hut above which flew a white flag. Captain Rod Bell was the interpreter. It was agreed to release the civilians and both sides left the hut. If there was a surrender it was agreed this would take place on an area of flat ground above the settlement at 13.30hours that day.

When the British contingent arrived all was quiet but it was known that the Argentinian troops had been seen packing their belongings. Suddenly, a column of troops, all air force personnel, marched towards the flat ground and formed into a hollow square. After being addressed by Air Vice-Commodore Pedroza they sang the Argentinian national anthem and laid down their arms. Air Vice-Commodore Pedroza marched over to Major Keeble, saluted and handed over his pistol. While this was going on more men arrived and they too formed a hollow square and were addressed by Lieutenant Colonel Pioggi and surrendered. 2 PARA suffered 15 killed and 30 wounded. 55 Argentinians were killed and between 8 and 100 were wounded.

News of the victory, when relayed to London, had the desired effect. It also enabled the remaining British forces to move out of San Carlos beachhead. Over the next few days a succession of intense battles and skirmishes took place as the British forces fought their way across East Falkland to Port Stanley. From the air the RAF Harriers attacked the Argentinian aircraft, most of which were based in Argentina. As the British forces trekked eastwards, the weather continued to deteriorate but the Mountain Leader Training Cadre of the 3 Commando Brigade successfully took Top Malo House on 31 May. The Fifth Infantry Brigade of 5,000 men, comprising principally of a battalion of 2nd Scots Guards, a battalion of 1st Welsh guards and Gurkhas were at San Carlos, 3,000 of them having come from South Georgia. With these additional troops, Major-General Moore could start looking at the retaking of Stanley.

Moving eastwards, first to Teal Inlet in the north of East Falkland, 3 PARA had left San Carlos beachhead after 2 PARA. Like 2 PARA, they had to go on foot through rough terrain as the Chinooks had been lost when the Atlantic Conveyor was sunk. They then advanced to Estancia, closer to Stanley, passing undetected north of enemy positions. With the help of local farmers the battalion established themselves waiting on an airlift to Mount Kent. The weather continued to deteriorate and they were in visible range of enemy guns. On 3 June they started the reconnaissance in order to take the strategic Mount Longdon overlooking Stanley. During the evening of 6 June President Ronald Reagan and Mrs Reagan arrived at Heathrow Airport, London, for a visit as a guest of the Queen. The Duke of Edinburgh welcomed the couple on behalf of the Queen and among those in the President’s retinue was Secretary of State Haig. The British welcoming party included Mrs Thatcher and Sir Terence. At the time, as far as the World and particularly the UN was concerned, Secretary of State Haig would be trying to negotiate a peaceful ending to the Conflict in order to save Argentina any humiliation.

Meanwhile, the Welsh Guard members of the Fifth Infantry Brigade were being taken to Bluff Cove, an inlet south of Stanley. Their transport was the landing ship Sir Galahad accompanied by the landing ship Sir Tristram. On the morning of the 8 June Argentinian planes took off for an attack and this was picked up by the submarine Valiant’s electronic-warfare mast. Northwood was immediately notified by satellite and the message was relayed to the Task Forces on the different parts of the Islands. Due to technical problems these were delayed until after the Argentinian air force flight arrived but some were met by Harriers on the look out. Some of those that made it through, dropped bombs four of which hit the frigate Plymouth in Falkland Sound but as the aircraft was flying low they failed to detonate.

In Bluff Cove, five Argentinian Skyhawks attacked the Sir Galahad and the Sir Tristram. 56 men were killed and over 150 were injured and of these, 38 Welsh Guards were killed and a further 19 were badly burnt. This was highest British casualty figure for any unit in the Falklands. The Guards belonged to the Prince of Wales and Third Companies and following the end of the Conflict, the ship was sunk and declared an official war grave. General Mario Menéndez, the Argentinian Military Governor, was told that 900 British soldiers had been killed and consequently informed Buenos Aires that he expected the British assault to stall.

On 10 June final preparations were made to capture Two Sisters, Mount Harriet and Mount Longdon, the high ground surrounding Stanley. As strategic positions they were well defended with Mine Fields and gun emplacements. Men from 45 Commando, 40 Commando and 29 Commando under Lieutenant-Colonel Andrew Whitehead and with naval gunfire support from Glamorgan, at 02.00hours started their assault on Two Sisters. It took all of that day against fierce resistance from the Argentinians to take the twin peaks. Lieutenant Colonel Nick Vaux, the commander, led 42 Commando into the Battle for Mount Harriet on the night of 11/12 June with support from 29 Commando and naval gunfire support from the frigate Yarmouth. Again the Argentinians put up fierce resistance as they were also doing at Mount Longdon, which 3 PARA were attempting to take. Mount Longdon was/is long and narrow with two peaks covered in rocks. To the east lay Wireless Ridge that continued eastwards to Moody Brook and to Mount Tumbledown. The estimated strength of the Argentinian forces holding Mount Longdon was 800 men supported by heavy artillery sited at Moody Brook.

The Battle for Mount Longdon started at 21.00hours on 11 June and was led by Lieutenant Colonel Hew Pike. Men from the 29 Commando Regiment and the Royal Artillery supported 3 PARA and the frigate Avenger provided naval gunfire support. Sergeant Ian John McKay (1953-1982) of 4 platoon of 3 PARA was on the northern side of Mount Longdon. As the platoon advanced they came under increasing heavy fire, along with 5 platoon, they were becoming increasingly beleaguered. The commander, Lieutenant Andrew Bickerdike, with some men, including Sergeant Mackay, reconnoitred the Argentinian gun positions to see how they could relieve their position. Identifying the heaviest gun position they took a closer look but it also contained a number of snipers with image intensifiers.

The Argentinian fire was accurate, one of the men was killed and six of the group were injured, including Lieutenant Bickerdike. The command devolved to Sergeant McKay decided to attack the position reasoning that by doing so it would relieve beleaguered 4 and 5 Platoons. Taking three men with him, Sergeant McKay broke cover and charged the enemy position, which was met by a hail of fire. One of the men was killed and two others seriously wounded. Nonetheless, Sergeant McKay continued to charge the position alone and on reaching it, knocked it out with grenades. Sadly, Sergeant McKay was killed but was awarded a posthumous Victoria Cross. The Battle for Mount Longdon continued to end at approximately 11.00hours on 12 June when 3 PARA finally secured it. An Argentinian prisoner later stated that ‘It was terrible! (Pike) threw company after company against us and we could not stop them. They kept coming even through the mortar fire, it was incredible! You have the bravest and most professional troops in the world.’ (Para! By Peter Harclerode – Brockhampton Press 1999).

The satisfaction of gaining the well defended three strategic high grounds was quickly dampened when on 12 June, Glamorgan was hit by an Exocet missile causing severe damage. Fourteen crewmen were killed and many more injured. Closing in on Port Stanley from the South West, on the evening of 13 June the British troops still had to secure three more well defended key positions. Two brigades consisting of Royal Marines, Paratroopers, Guardsmen and Gurkhas began advancing from the high ground and all met with fierce resistance.

As the Scots Guards were battling for Mount Tumbledown, the Gurkhas, under gunfire, went along the line of Goat Ridge, to the north of Tumbledown. They were preparing for their assault on Mount William once Mount Tumbledown was taken. As dawn approached on 14 June, the Guards had still not secured Tumbledown so the Gurkhas made the dangerous but successful daylight assault on Mount William. When the Argentinians were taken prisoners they saw the Gurkhas unsheathed their huge curved ‘kukri’ knives. Terrified that the soldiers were going to decapitate them they feared the worst until the Gurkhas started to use the knives to cut up boot laces to tie the prisoners hands together! Meanwhile, 2 PARA ,with light armour support from 3 Troop of the Blues and Royals, made the successful assault on Wireless Ridge.

A Company of 2 PARA, at 13.30hours on 14 June, were the first British troops to enter Stanley and soon after they were joined by other British troops. Although General Menendez had 8,000 troops in the area when they met the British troops, they laid down their arms. General Galtieri, in Buenos Aires, ordered General Menendez to stand firm and to continue the fight but General Menendez decided to negotiate. Sir Terence was informed and immediately went to the Fleet’s operational headquarters at Northwood. That afternoon, the Islanders besieged in Stanley’s West Store were surprised to hear a knock on the door. When they opened it there stood Major General Jeremy Moore. He greeted the islanders saying, ‘Hello, I’m Jeremy Moore. Sorry it’s taken rather a long time to get here!’

At 18.00hours on 14 June the message was received that the Argentinian garrison were prepared to discuss surrender terms and two hours later General Menendez, after speaking with General Galtieri, met with Brigadier John Waters, Major General-Moore’s deputy, at Moody Brook. Sir Terence returned to London and the surrender document was drawn up covering enemy forces both on West and East Falkland. This was transmitted to Major-General Moore who immediately went to Moody Brook to discuss the terms. However, shortly after the surrender document was sent the communication network between London and Stanley broke down. Luckily, the SAS had a direct radio link between their headquarters at Credenhill, Hereford and Stanley so from Hereford a full commentary of what was happening was relayed. This was by ‘phone to Northwood and from there to the War Cabinet Room in the Commons.

In the War Cabinet Room Mrs Thatcher, along with Sir Terence and John Nott, were drafting out the announcement of the surrender. Mrs Thatcher hoped that news of the confirmation of the surrender would come before 22.00hours so it would make the main British news broadcasts at that time. As discussions on details were still taking place in Stanley the Prime Minister went into, the by then packed, Chamber of the House of Commons. To an elated welcome she told MP’s that the White Flags of Surrender were flying over Stanley and that the final surrender was expected at any time. At midnight General Menendez formerly surrendered all Argentine Forces in both East and West Falklands to Major-General Moore, the Commander British Land Forces, Falklands. Sir Terence and John Nott went to the Ministry of Defence to meet the media and answer questions. At the same time Mrs Thatcher announced that the victory was won by an operation that was ‘boldly planned, bravely executed and brilliantly accomplished.’

On 20 June the British retook the South Sandwich Islands and declared hostilities to be over. By that time 3 Falkland Islanders, together with 255 British and 649 Argentine members of the armed forces, had been killed, over half of the latter due to the sinking of the Belgrano. 89 Royal Navy, auxiliary and merchant ships were involved in the campaign. The following day, 21 June, Diana, Princess of Wales (1961-1997) gave birth to Prince William. His uncle, Prince Andrew, saw action in the Falklands Conflict on board Invincible as a Sea King helicopter co-pilot.

In October 1983, Sir Terence retired as Chief of the Defence Staff, but on 27 October the Commons Defence Committee called him to answer questions. In the grilling Sir Terence was asked why he and his colleagues had deliberately used misinformation and censorship to the British media during the Falkland operations. The Committee had previously heard severe criticism from the Press Association that as a free press it was up to individual editors to make such decisions. Sir Terence responded saying that his job was to help to win the war and that he would not regard the information released as misleading the press and the British public but as misleading the enemy. Saying ‘Anything I can do to help win is fair and I would have thought that the media and the public would want that too.’ (Hansard)

The Select Committee also wanted clarification on the haste of the operation saying that many believed it to be a politically motivated attempt to undermine the peace talks. Sir Terence response was that the Falklands operation could not be delayed much longer that year due to the Islands location in the South Atlantic, and most notably, the weather. He went on to say that by the following year, 1983, due to the ongoing run down of the armed services and particularly the Fleet on which the Task Force’s reliance was ‘crucial, such an operation could not have been mounted.’ Adding, in essence, that ‘the Conflict demonstrated a classic failure of deterrence … The consequences of not demonstrating to a potential enemy sufficiently clearly that you have both the political will and the military capability to deter aggression.’ There were a number of occasions that he deeply regretted, Sir Terence said, the ‘dead and wounded on both sides but’, he added, ‘ that the campaign was a worthwhile exercise for the free world.’ He finished by saying that ‘it was fortunate that the three sectors of the British Armed Forces were first class and well trained.’ (Hansard)

Within days of Stanley being retaken, General Galtieri was removed from power along with other members of the former junta. He was arrested in late 1983 and charged in a military court with human rights violations and with mismanaging the Falklands War. In May 1986, General Galtieri was found guilty of mishandling the war and sentenced to twelve years in prison. Also convicted were 39 officers including Admiral Anaya and Brigadier Basil Dozo and in 1988 Galtieri, Anaya and Dozo were stripped of their rank. Two years later, in 1990 Galtieri and all the officers received a Presidential Pardon. Twenty-two years after the Conflict, in 1994, the Argentinian Government announced that the sinking of the Belgrano was a ‘legal act of war‘ but still claimed sovereignty over the Falklands.

Following the Conflict, the proposed cutbacks of the Royal Navy fleet was abandoned and replacements for many of the lost ships and helicopters were ordered including more Sea Harriers. Sir Terence was given the task of restructuring the Armed forces, for which, in the New Years Honours list of 1984, he was created Baron Lewin of Greenwich. Baron Lewin died on 23 January 1999 when he was cited as being, ‘one of the greatest military leaders of the late 20th century.’ Yet, he has not received any recognition in the town of his birth. Further, Dover’s status as a garrison town finally came to an end, after over a thousand years in February 2006 when Connaught Barracks closed. Ironically, with regards to this story, it was the 1st Battalion of the Parachute Regiment that marched away from Dover that day.

Presented: 13 May 2016.

- A short pre UK 30-Year Rule account of the Falklands Conflict was published in the Dover Mercury 26 November 2009

- and in the Dover Society Magazine, March 2011.