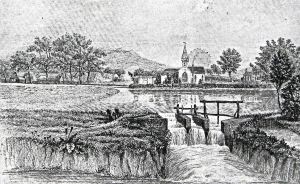

1948 map of Dover showing the course of the River Dour from Crabble to Wellington Dock

The story of Dover’s four mile long River Dour has been divided into two parts and the first part is subdivided into three parts, the first gives an overview in an historical context. Rising at the appropriately named Watersend in Temple Ewell with the main tributary coming in from the Alkham valley, the Dour passes through four villages and through a greater part of the town of Dover before flowing into the Wellington Dock. The second subdivision is an overview of the history of the four villages that the river passes through, Temple Ewell, River, Buckland, and Charlton. The final subdivision briefly covers the ecological plight of the Dour from when it was declared as a mere watercourse in 1901 to being officially declared a river in November 1993 and the problems that still exist today. Part two of the River Dour story is a virtual walk along the River Dour Trail.

Historical Overview of the River Dour

Dover is famous for the White Cliffs and the fact that the town and port are closer to Continental Europe than any other part of Britain. By coincidence the only significant gap in the famous cliffs, on the English side, is at Dover and this has made the port the natural destination for Continental traders, migrants and invaders alike. The history of the town and port are inextricably linked to the geographic location and therefore they have played a significant role in the grand panorama of events associated with the country as a whole. The cliffs on either side of the town rise to 350 feet (110 metres) at the seaward end and are comprised of chalk and black flint. Yet the gap was created, over thousands of years, by the, just less than four miles long, River Dour!

Brown trout in the Dour alongside Barton Path. AS

One of only two pure chalk streams in Kent the Dour, brown trout, these days, spawn in the gravel bed. The river is narrow, not particularly deep but flows constantly as it is fed by numerous springs. It is these that give the river it’s high calcium content and although it should be low in silt, due widening of the river for industrial purposes from the early 19th century and, more recently, the dumping of rubbish, the build up of silt has caused ecological problems. Nonetheless, it is almost certain that this diminutive river helped to create the great Dover Bay. Not only that, but because the river is fed by numerous springs, it has ensured the port of Dover has survived long after sister harbours, along the coast, have ceased to be of international importance.

At least two million years ago the first humans appeared in Africa. Gradually nomadic hunters spread to the European Continent about 700,000 years ago. At this time, south eastern Britain was linked to Continental Europe by a wide land bridge that allowed humans to cross freely. In 1956, when the ground was being prepared to build the National Provincial Bank on the west side of Market Square a mammoth tooth was found, said to be 500,000 years old! The following year, on the same site, ‘pot boiler’ flints, used to heat liquids, were found and in 1970 excavations by Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit (KARU), uncovered a late Stone Age (Neanderthal) ‘extensive forum’ beneath the centre of Dover.

Some 18,000 years ago an ice sheet covered the northern part of Britain and the dust from the ice fields were deposited in what is now East Kent and these contributed to the course of the river Dour. During the Mesolithic period, from 8,000-4300 BC, rising seas finally broke through the connecting Continental land bridge, by which time the locality was well occupied. Excavations by the Canterbury Archaeological Trust (CAT) prior to the building of the A20 from Court Wood to Aycliffe, found Mesolithic to Neolithic (4300 BC – 2500 BC) flint tools and waste flints. On the steep east side of the Dour valley, near Hobart Crescent -Buckland estate, archaeologists found a pre-historic burial ground.

It is due to the Dour cutting through the chalk cliffs, providing water and shelter for these early settlers, that Dover owes its existence. In early times the river would have been much wider and deeper than in the last millennium with wide tributaries. These came from the west cutting the chalk hills into broad almost parallel valleys. The steeper east side of the Dour valley lacks any such terrain but nailbournes – intermittent streams fed by underground springs – were, and still are, in abundance. These features have had a lasting influence on the development of the town.

Bronze Age c1100BC artefacts found by Dover Sub-Aqua Club in Langdon Bay in Dover Museum. LS 2014

During the Bronze Age, from about 2500 BC to 700 BC, there is evidence of a significant growth in the population of the area. Not only in the fertile valleys to the west of the Dour but there is evidence of soil erosion on the steep sided eastern flank. This suggests that this side of the valley was also cultivated. On 14 August 1974 divers Simon Stevens and Mike Hadlow of the Dover Sub-Aqua Club found bronze artefacts dating from around 1100 BC at Langdon Bay, to the east of the present Dover harbour. These included winged daggers and spearheads and over the following years some 400 similar items, as well as jewellery, were recovered. Most of these are now in the British Museum but there is a small display in Dover Museum.

Of particular note, bronze is an alloy made from a combination of copper and tin, neither of which are found in this part of England or northern France. While the artefacts, on the whole, appeared to have been used or damaged in some way. This suggests that the bronze artefacts came from further afield, possible from Alpine areas. This has led to the speculation that the finds were the cargo of a Bronze Age scrap metal dealer and were probably going to be recast into tools! The site where they were found is protected under the 1973 Wrecks Act.

Bronze Age Boat discovered under Townwall Street. Nick Edwards 28.09.1992.

Other Bronze Age artefacts have been found around the area and these include a priceless gold cup that was found in 2001. However, the greatest find of all, so far, occurred on Monday 28 September 1992, by CAT archaeologist Keith Parfitt. This was the earliest sea-going craft in the world! Discovered in what was once the wide estuary of the river Dour at the bottom of present day Bench Street, the boat was built of oak about 1550 BC. Under the auspices of the Bronze Age Boat Trust, it has been specially preserved and is now on displayed in Dover Museum. It was believed that the Boat was capable of carrying a significant cargo, could travel at a reasonable speed, in fairly rough weather and possibly over long distances. A half size replica has been made and the seaworthiness and ability to carry significant cargo have been proved – as this author can testify. Whether the original Boat was capable of crossing the Channel is, as yet, to be proved by the replica.

The Iron Age (700BC- 43AD) is characterised by the introduction and spread of iron tools and weapons. Although iron is found in abundance, it is far more difficult to work than bronze. Archaeological evidence is increasingly showing that Dover was economically closely tied to northern France, especially the French port of Wissant, and this was undoubtedly for the purposes of trade. In July 1991, again during the building of the A20 between Court Wood and Aycliffe, archaeological investigations revealed pottery of the late Bronze Age/early Iron Age transition period. Iron Age objects have also been found on the Western Heights, including a small farmstead from circa 300 BC, while investigations, published in 1963, suggest that the configuration of earthworks on the Eastern Heights, where the Castle now stands, was an Iron Age fort.

It is thought that the Celts, who were highly skilled craftsmen, may have inhabited the Dover area. Albeit, with the expansion of the Roman Empire, immigration of Belgics from northwest mainland Europe did take place. The latter formed large settlements including one near Court Wood, where archaeologists have found a considerable quantity of materials relating to this Belgic as well as early Roman occupation. In 1990, Sue Lee, a local historian/archaeologist alerted Brian Philp of KARU to what turned out to be four Iron Age cremation burial sites in the Alkham Valley. These dated from about 50 BC and two contained large wooden buckets decorated with bronze heads, sheeting and fittings. The finds are now in the British Museum but other finds, including a pedestal urn along with a replica of the buckets a can be seen at the Roman Painted House Museum on New Street.

Romans – Memorial of Julius Caesar landing place at Walmer. LS

In 55BC, Julius Caesar (100BC- 44BC) commanded a conquering expedition to Britain aiming to land in the Dour estuary. At this time, the lower reaches were at least 200metres in width. In the Commentaries on his campaigns, written in the third person, Caesar tell us that he was ‘determined to proceed into Britain because he was told that in almost all the Gallic wars succour had been supplied from thence to our enemies.’ With his fleet of 80 ships and two galleys, on 25 August he ‘reached Britain with the first squadron of ships about the fourth hour of the day, and there saw the forces of the Britons drawn up in arms on all the hills. The nature of the place is this: The sea was confined by mountains so close to it that a dart could be thrown from the summit to the shore…’ Calling this place Dubris (meaning waters), it is generally accepted that Julius Caesar was describing Dover.

Caesar goes on to describe how the British forces were marshalled on the Eastern and Western Heights in ways that persuaded the invaders to take the next flood tide east where they landed at Walmer. There the Britons, who had followed in chariots and on horseback, attacked the Romans but the invaders were victorious and made camp on the beach. Afterwards, Caesar’s view of the Briton’s changed, for he writes, ‘…by far the most civilised are those who inhabit Cantium, the whole of which is a maritime region; and their manners differ little from those of the Gauls’. Cantium means rim or border and the modern name Kent is derived from it. However, after surveying the area, Julius Caesar and his troops sailed away.

In the summer of 43AD, Claudius Caesar (41AD-54AD) ordered the invasion of Briton for the Roman Empire. Their invasion force of approximately of 40,000 troops, under Aulus Plautius (44BC-01AD), landed at Richborough, near present day Sandwich. There he established a bridgehead and commemorated the success by building a triumphal arch whose cross-shaped foundations still survive. It was following this invasion that the Romans built a harbour on the wide river Dour estuary. However, like many of the stories appertaining to the Romans and Dover following Julius Caesar’s visit, this assertion was seen as local folk-law by professional archaeologists and other intellectuals. That is until 1856, when workmen were excavating a site on the former Fector estate, which fronted St James’ Street, for a gasometer.

About twenty feet beneath the surface, the workmen came across a framework of English oak timber, of an average width of about twelve feet. This was constructed of four longitudinal beams on each side – all about a foot square – laid upon one another and from each of these beams, traverse ones had been placed at a distance of about eleven feet apart. The frame had a slight downward incline towards the River Dour and the timber, though discoloured by water, was as sound as when first used. Though strongly built, the structure only had a few bolt or peg fixings. At the time this discovery excited much interest. None more so than Dover’s then town clerk, Edward Knocker (1804-1883) who made a model of the framework out of oak. It was recognised by those who had previously rejected the notion of Dover being of significance during Roman times. It was agreed that the finds had been laid down ‘by the Romans as a hard or roadway to and from their landing place on what was a boggy shore, and it must have been constructed at least 1,500 years ago.’ In other words a Roman quay.

Roman Pharos and St Mary in Castro Church in Dover Castle grounds. LS 2013

In his subsequent account, Knocker, made reference to the Roman Pharos or lighthouses. At that time besides the one on the Eastern Heights there was the ruins of a corresponding one on the Western Heights. The one on the Eastern Heights, to be seen in the Castle grounds, is the oldest surviving building in Britain and is some 43-feet (13-metres) in height. Research since Knocker’s time has shown that General Aulus Plautius, who began the Roman conquest of Britain in 43AD, became the first governor of the new province, serving from 43AD to 47AD. It was during this period that a fortified ‘castle’ with towers and earthworks was built on the western side of the Dour estuary with quays along the riverbank. Across the estuary, sea walls were built in a straight line between the two Pharos and in the centre was the harbour entrance.

The Pharos were built from blocks of tufa, a form of limestone formed by the shells of minute fish accumulating around a nucleus, such as flint. The tufa used at the times of the Romans almost certainly came from the bed of the Dour as it has been found in many places along the Dour valley. Most notably in St Andrew’s Churchyard – Buckland, London Road, Barton Road and the Peter Street area. It is said that a bed of tufa, up to 4-feet thick, lies under what was the playground of Buckland School, now a private housing concern. These days tufa is still found along the valley of the Dour but this tends to be friable unlike the hard tufa used by the Romans.

Stylised drawing showing the Classis Britannica, Pharos on the eastern and Western Heights and Roman harbour. Dover Museum

Continuing his interest in the Roman Quay, in about 1860, Knocker reported piles, groins and mooring rings in the then ancient Dolphin Lane area. This indicated, and more recent evidence confirms, that over time the Romans probably reclaimed land along the west side of the estuary gradually moving the harbour quays eastwards. However, it was not for another 110 years before local amateur archaeologists were taken seriously and the claims excavated. KARU under the direction of Brian Philp found buildings that made up the Classis Britannica Fort, built about 130AD and the base for the Roman Fleet in Britain.

A later and larger fort, built by the Romans, was unearthed, believed to be a part of the Roman Shore Fort series of forts. These were erected around 270AD along the coast to protect the Roman occupied territories from Saxon incursions. In 1956 a length of chalk-block quay, supported by piles and planks, was found at Stembrook and this is now believed to represent part of a waterfront from that time. In 1974 a trial-excavation near Bench Street located another deeply buried chalk-block structure and this may represent a continuation of the Roman waterfront.

Schematic Map c1974 of the location of the Classis Britannica and the Roman Shore Fort. St Martin’s cemetery is shown at the bottom. KARU

More recent work has shown that the River Dover was tidal and navigable as far as Charlton Green one-mile inland, when the Romans built the Classis Britannica. At that time the harbour was probably to the east of where the River now flows. It is conjectured that due to earth being washed down the valley by the Dour meeting the shingle washed into the estuary by the sea, a shingle bank formed. For this reason, the Romans moved their harbour westward reclaiming the site behind the shingle bar. This accounts for where the Roman Quay was found by Knocker in the mid 19th century.

During the Roman occupation an adjacent settlement of locals almost certainly grew to meet the needs of the invaders and farming was being undertaken. At the time there were two roads out of Dover one to Richborough and the other, Watling Street, to London. Watling Street followed the course of the River Dour and it is almost certain that the fertile banks of the Dour were used for agricultural and husbandry purposes.

As rulers, the Saxons (c450-1066) followed the Romans and in 596AD, Augustine, a Benedictine Monk, arrived and introduced Kent to the Christian religion. A year later he became the first Archbishop of Canterbury and converted Æthelberht King of Kent (c589-616). Soon after the King’s son, Eabald (616-640), founded a college for the Secular Canons in Dover ‘castle’. The castle referred to, at this time, is believed to be the old Roman Shore fort. In 691AD, Wihtred (c.690-725), King of Kent, following a victory in battle that was attributed to St Martin, ordered a new monastery to be built in the Saint’s honour for the Canons at Dofras – the early Saxon name for Dover. Material for the new monastery was brought by ships that were unloaded on quays on the west side of the Dour.

Ruins of St Martin-le-Grand by the steps of the entrance to the Dover Discovery Centre, Market Square. LS

Following the Bapchild Royal Council of 697AD, the Canons were endowed with grants of large tracts of land – including along the Dour at Buckland and Charlton. They were also given the lucrative tithe of the passage of the Port of Dover. Albeit, while the new monastery was being built it was frequently the target of attack from sea marauders. To help combat these, King Wihtred ordered the building of a seawall across the Dour estuary.

The farmers along the River Dour continued to provide food for the growing population and the first written record of a corn mill in Britain was in 762AD. The mill was on the Dour in the locality that has been identified as Buckland. Long before the end of the Saxon period, a corn mill at Charlton was recorded and it is known that the Canons’ of St Martin-le-Grand had a water driven mill on the Dour – probably the Town Mill. By 1000AD, Dover, renamed Doferem, was a prosperous town with an established mint and cross-Channel trading links. It was also the head of the Cinque Ports Confederation and Dover was providing a base for royal fleets. Following the Norman invasion of 1066, William I (1066-1087) made a grant to the town’s Burgesses to ensure the harbour remained a base for the Royal fleet.

Map showing the Dour estuary c1086 with the location of St Martin-le-Grand, St Mary’s & St Peter’s Churches, town mills and Iron Age fort on Eastern cliffs. This author’s understanding from a talk by Keith Parfitt of Canterbury Archaeological Trust 2016

The King also effectively created palatinates and the Kent palatinate was under his half-brother, Odo the Bishop of Bayeaux (d1097). The Domesday Survey of 1086 gives a description of a mill sanctioned by Odo, ‘ in the entrance of the port of Dovere, there is one mill, which damages almost every ship, by the great swell of the sea, and does great damage to the king and his tenants; and it was not there at the time of King Edward.’ From this it is assumed that the Dour estuary had narrowed from Roman times and was relatively narrow and fast flowing at that time.

It is believed by many that Odo’s tidal mill allowed the build up of silt and contributed to the Dour forming two riverlets, the existence of which is well documented. Initially they were called the East and West Brook but are frequently referred to as Eastbrook and Westbrook. A survey carried out by Dover Harbour Board in 1988 found gravel about 10metres east of Admiralty Pier indicative of an old river bed. It has been assumed that this was Westbrook’s entry into the sea. Eastbrook took a more easterly direction and it emptied into the sea near Warden Down – the cliff that Castle Hill Road traverses. It was close to here that a harbour was built and was approached through Eastern Gate. Around this harbour the medieval mariners settled.

The Eastbrook harbour became the town’s main harbour and over the next 300 years this harbour proved to be a great success, with royalty, both English and foreign, using Dover as the principal port for passage to and from the Continent. However, the sea began to encroach and floods became a regular occurrence. To protect the town, a retaining wall was built from what is now the Snargate Street/Bench Street area to the west side of Eastbrook. Called the Wyke, an inlet had formed at the west side of the Eastbrook. Shipbuilders utilised this as an entrance to what became the town’s shipyard, in the area behind the Wyke. In 1440, Henry VI (1422-1461) granted a Charter to encourage Dover’s shipbuilding industry.

The town and its harbour continued to come under attack but not without cause (See Cinque Ports part II). To protect both, at the latter end of the 14th century, strong town walls were built. Within these, in 1370 a new gate, called Snar Gate, for the Westbrook of the Dour to exit the town into the sea was erected at the bottom of the present York Street. Between 1300 and 1500 there was a movement of land mass that triggered the phenomenon called the Eastward Drift – the tide sweeping round Shakespeare Cliff and depositing masses of pebbles at the eastern end of the bay.

Wyke or Wick Tower – built by John Clarke c1500. From a British Museum print. Dover Library

This, together with a cliff fall at the beginning of the fourteenth century, rendered the Eastbrook Harbour useless and over the succeeding centuries it silted up. The cliff fall, apparently, cause the Eastbrook of the Dour to take a westerly serpentine direction eventually joining with the Westbrook. At the same time the Wyke had ceased to be effective in protecting the town from floods and the building of a new Wyke commenced. This started at Snar Gate and ran along the whole sea front of the town.

The loss of the Eastbrook Harbour had a devastating effect on the town’s economy which in turn had a knock-on effect on the livelihoods of the inhabitants further up the Dour. The Corporation saw hope by turning a natural anchorage at the foot of Archcliffe Point into a harbour. Sir John Clarke, Master of the Maison Dieu sought Henry VII’s (1485-1509) patronage and built a new harbour that the mariners called Paradise Pent. However, in the autumn of 1539 a series of southwesterly storms deposited pebbles into the entrance of Paradise Pent and also where the Dour discharged into the sea.

Conjointly, this caused serious flooding and Mayor John Bowles petitioned Henry VIII (1509-1547), who in 1540 set up a Commission to investigate. Over the next two years, solutions were put forward to the King, but having already spent a great deal of money on Dover’s harbour for his fleet, he declined to spend any more. By 1566 an offshore shingle bar had built up across the Bay from Archcliffe to the foot of the Castle cliffs. This enclosed a tidal lagoon into which the Dour flowed.

Harbour c1590 on the completion of Thomas Digges work. Drawn by Lt Benjamin Worthington c 1836. Dover Library

Having gained experience in the Netherlands, engineer Thomas Digges (c1546-1595), of Wooton, in 1581, came up with a revolutionary design to deal with the problem. He proposed strengthening the naturally formed shingle bar that had created the lagoon into which the Dour flowed. This he did using faggots covered with earth, held down with piles. The resultant long wall was parallel to the shore and to this, he joined a strengthened shingle embankment running from the end of of the natural long wall and formed what is now Union Street.

It also enclosed a large area into which the Dour flowed and was called the Great Standing Water or Great Pent. A floodgate and sluice were inserted in the embankment that is now Union Street which enabled the Great Pent to empty into Paradise Pent and clear any shingle blocking what was then the harbour. To relieve the River Dour during periods of heavy rain that caused flooding a sea wall, parallel to what is now Snargate Street was built with sluices and floodgates and called the Great Paradise. Costing £7,495, work began on 13 May 1583 and finished about 1586.

Over the next three centuries many alterations and modifications were made to the harbour then, in 1830, a major refurbishment to the Great Pent was undertaken. This included removing some 20,000 tons of mud that had been deposited by the River Dour and the new dock was deepend. It was then lined with granite and two 60-feet (18.3 metres) giant lock gates were inserted that provided access and egress between the Great Pent and the Tidal Basin.

An iron bridge was built over them and the whole enterprise was completed in 1844, costing about £45,000. The Lord Warden, the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) opened what was formerly the Great Pent along with the bridge on the 13 November 1846 and they were named, respectively, Wellington Dock and Wellington Bridge. Sluices were inserted at the side of the dock gate to relieve over filling of the new dock from the Dour during stormy weather.

New Bridge at the time it was built in 1800. Dover Museum

Further up the river to the east of the then Great Pent, in 1800, a bridge was built across the Dour to enable folk to access the seafront and beach. Appropriately named, New Bridge, on the west side John Hillier had a builders yard. In 1826 William Batcheller bought Hillier’s yard and built a fine Regency mansion called Kings Library in which he opened a library and assembly rooms and where the high society of Dover subsequently met. The eastern parapet of New Bridge was removed in 1840 to enable widening and premises were built from Bench Street across the bridge.

The area around New Bridge, however, was devoid of lamplight and reeking with all kinds of filth. In March 1852, the Harbour Commissioners appointed Henry Lee & Sons of Chiswell Street, London to construct quays around, what was by this time, Wellington Dock. That year the parapet on the west side of New Bridge was removed to provide access into the newly constructed Northampton Street (now gone) and Quay. A 10foot to 14foot diameter culvert was built under Northampton Quay for the Dour to flow into Wellington Dock.

Northampton Quay was still being built when it was decided to extend the brick culvert carrying the river Dour by 330feet and this was strengthened using Medina cement and bricks to form ‘masses 2feet long.’ The Medina Cement Company had been established on the bank of the Medina River, Isle of Wight, around 1840 and by the mid 19th century, the company had acquired the reputation as a pioneer in cement concrete. For a number of years it rivalled Portland cement, exhibiting at the 1851 Great Exhibition and securing government contracts. The two products had quite different properties, Medina Cement was a ‘roman’ cement and quick drying, while Portland was slower drying but ultimately considered stronger.

New Bridge looking towards Bench Street, Cambridge Terrace on the left and new Bridge House on the right note buildings on the bridge c1900. David Iron

Once the culvert was completed, exclusive properties were built from the Batcheller’s Kings Arms Library over the Dour culvert to reclaimed land beyond. When finished in 1856 the new properties were called Cambridge Terrace and to take their weight the Dour culvert was further strengthened which narrowed the aperture. In 1864-1865, opposite Cambridge Terrace, New Bridge House was erected.

Throughout this time Admiralty Pier, construction was started in November 1847, followed by the Admiralty Harbour which was finished in 1909. Together with the narrowed aperture culvert and the reduction of sluices to relieve excess water in the Wellington Dock, resulted in an unwanted effect. During heavy weather and when tides are exceptionally high, water from the Wellington Dock cannot flow out and therefore the Dour river waters back-up. Exacerbating this problem, during the 19th century the Dour flood plains, particularly in Dover, were used for building purposes. Hence, when there is a combination of heavy rain and high tides Dover becomes susceptible to flooding.

Villages along the River Dour

As stated at the beginning of this story, the Dour passes through the villages of Temple Ewell River, Buckland, and Charlton before going through Dover and emptying into the Wellington Dock. The next part of this story takes a brief historical look at these four villages.

Temple Ewell

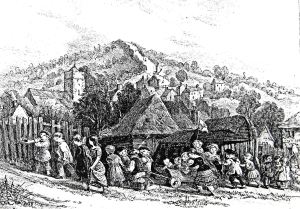

Temple Ewell children climbing the hill to Lousyberry Wood with village and Ewell Minnis in the background c1900. Dover Library

Temple Ewell is the village in which the Dour rises at Watersend and in Saxon times was known as Æwille, meaning river source or spring. The village has a long history for it was mentioned in a charter of around 772AD. Surrounded on three sides by high cliffs and there would have been on the fourth side if the Dour, in ancient times, had not carved out the valley that cuts through the south side. The Romans utilised this opening when they built Watling Street through the village. By the time of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), Edrich de Alkham was the landowner. Of note, the Dour’s main tributary starts from east of the village of Alkham and runs along the Alkham valley.

Following the Conquest of 1066, the area came under Norman ownership and in the Domesday Book of 1086, the village was called Ewelle or Etwelle. It was recorded that there was a manor house, five watermills, about fifty homes and a wooden church. In 1163, the Knights Templars, the major fighting force during the Crusades, were given Ewelle in recognition of their work for which the village was given the prefix Temple. It was they who built the Church, not far from the River Dour, from which the present St Peter and St Paul Church evolved. Indeed, the original eight pointed cross emblem of the Knights Templars can still be seen in the present Church.

The converted former corn mill Temple Ewell. Alan Sencicle

Traditionally, the village was predominantly a sheep rearing and arable farming community and like all such villages, had a corn mill that was situated on the river Dour. This was built by the Knights Templars and rebuilt in 1535. Alfred Stanley senior bought Temple Ewell Mill for £100, and in 1870, his son built a second mill nearby. By 1957, this was the last working corn mill on the river Dour and was owned by Alfred Stanley, the great-grandson of the original Alfred Stanley! Much of the first Temple Ewell mill was demolished to make room for housing and the second mill closed in 1967. Four years later, it was bought by Dover Operatic and Drama Society to provide rehearsal rooms and storage facilities. Nonetheless, structurally, the building is a fine example of a mid-19th century corn mill.

The village school, next to the Church, opened in 1871 and over time has been extended and continues to thrive with high ratings from the Ofsted – Office for Standards in Education, Children’s Services and Skills who inspect and regulate services that care for children and young people, and services providing education and skills for learners of all ages. Up until the opening of the new A2 in 1974, the London Road made the village a major accident black spot but today it is much quieter. The thriving Community Centre, built in 1909, is next to London Road and has the look of an old village school and at one time, the village boasted of four pubs.

River Dour, Lower Road, Temple Ewell. Alan Sencicle

In the late 19th century, a massive coalfield was discovered under East Kent and the Brady shaft at Shakespeare Colliery was started in July 1896. A total of 14 coal seams, stretching from Dover almost to Herne Bay, were eventually found and it was envisaged to sink 15 mines, one of which was at Stonehall, Lydden, the next village to Temple Ewell towards Canterbury. The colliery was not commercially viable and was finally abandoned in 1923 due to proneness of flooding. In the 1970s the National Coal Board under took boring to evaluate the extent of the flooding and if it could be contained using modern technology. Water was pumped out and into the Dour but in 1978 this caused serious flooding in Temple Ewell. The National Coal Board were forced to change their policy and the Stonehall project was abandoned although, it is believed, that water is still pumped from the old mine into the Dour.

These days, only the Fox Inn, in the centre of the village, remains. Temple Ewell also has a village shop and at one time there was a butchers, a cobblers and a black smiths amongst other trades. The building of the housing estate on the east side of London Road, Target Firs, dramatically increased the size of the population of the village. Many of the new female residents were employed at either the Watersend pickle factory or Alexander Couchman’s sweet factory in Target Firs. Both factories have long since disappeared but the housing estate has grown considerably.

Much of the old village developed around the River Dour and between Temple Ewell and the next village along the Dour – River – is the hamlet of Kearsney. The Lower Road follows the Dour and crossing the road, on a high viaduct, is the railway line from London via Canterbury to Dover. Built by the London, Chatham and Dover Railway company Kearsney railway station serves both Temple Ewell and the village of River. After passing underneath the Alkham Valley Road, the river Dour enters Kearsney Abbey parkland where it is joined by its tributary from the Alkham valley and forms a lake before entering the village of River.

River

Map of Watling Street, South Eastern & Chatham Railway line between Dover and London, River, Temple Ewell and Kearsney c1919

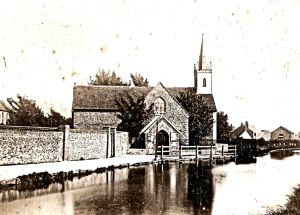

The village of River comes after Kearsney Abbey and its name causes a great deal of confusion to people who do not know the area. In fact it was named such because the River Dour runs through it! Although long ago River ceased to be a rustic village and in 1903 became part of the Borough of Dover, like Temple Ewell, it has maintained its own identity. The church of St Peter and St Paul is on the corner of Lewisham Road and Minnis Lane, on the west side, on the hill above the Dour.

The Church can trace its origins back to 1208, was rebuilt in 1832 and restored in 1876. Initially, it was dedicated to St Peter but later it was rededicated to SS Peter and Paul, only to revert back to just St Peter. Then there was another change of mind and it was rededicated in 1876! Of interest, all the village churches along the Dour are dedicated to apostles who were fishermen and at one time Dover also had a church dedicated to St Peter – as can be seen on one of the maps above – it too was next to the Dour!

River Paper Mill ruins, Lower Road – Common Lane , River . Alan Sencicle

Minnis Lane is the first road on the right after leaving Kearsney Abbey by the footpath along the Dour. Near the bridge over the Dour are the ruins of what was once River paper mill and further along the Lower Road is a present branch of the Co-operative Society. Between the two and now a residence, was the original Dover Co-operative Society building founded by mill workers. Having previously supported its own Poor House, the River Union Workhouse on Valley, serving 13 rural parishes was adapted from an earlier building. This cease to exist in 1836 when the Union Workhouse, which later became Buckland Hospital, was built in Dover.

The arrival of the London, Chatham and Dover Railway in 1861 led to an influx of wealthier households and the demand for new homes led to a thriving brick making industry within the village. As the desire for more houses increased the steep hills on the west side of the village were developed but commercially produced building materials put an end to the local brick makers. Because the London Road is high on the steep escarpment on the east side, the village has never been laid prey to the volume of traffic that once blighted Temple Ewell.

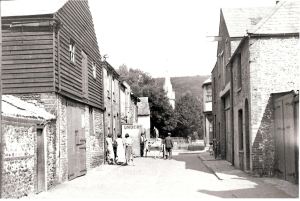

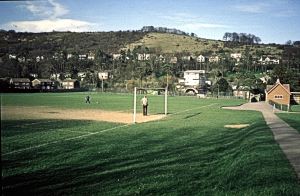

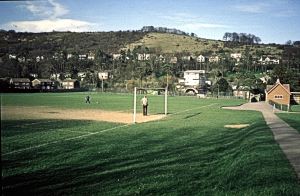

River Recreation Ground 1988 with Old Park hill in the background. Dover Museum

There has been a village school in existence since before 1871 but in that year the school was taken over by John Judges and rebuilt on Lewisham Road. Since then, the school has been extended, refurbished, had makeovers and then a rebuild, all to meet an increasing demand for school places. In 1922, a village hall was erected out of corrugated ex-Army huts that had been used as a military hospital during World War I (1914-1918). This was land given by local market gardener Councillor Hilton Russell, the driving force of the later Russell Gardens. However, by the 1950s, the Hall was in a poor condition.

On the instigation of Hilton Russell’s son, Ray Russell, money was found, the hall was re-established and more recently rebuilt. Between Lewisham Road and Lower Road, is River’s large recreation ground. Back in the late 1980s Dover District Council (DDC) passed a covetous eye in order to raise money for their pet project, the short lived White Cliffs Experience, and ear marked the recreation ground for housing development. Vociferous protests that unified the village ensued and DDC backed off.

Crabble Mill on the Dour river. Alan Sencicle

From River the Dour runs alongside the Lower Road through the picturesque hamlet of Crabble. Although Crabble corn mill has long since ceased to be a commercial flour producing operation, these days it is recognised as one of the finest examples of a working Georgian water mill in Europe. The nearby new build housing, on the whole, does not detract from the character of Crabble. The once large Crabble paper mill that stood by the southerly main road in and out of River, has been converted into a sympathetic housing development.

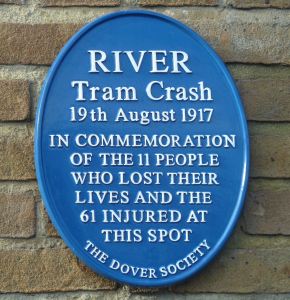

An electric tram track opened to River Church along Crabble Hill Road and Lewisham Road on 2 October 1905. On Sunday 19 August 1917 one of the worst tram accidents in the country occurred on the bridge that goes over the River Dour. In the Crabble Tram accident 11 people were killed and 60 were injured, many seriously. On the bridge there is a Dover Society Plaque to their memory. On the opposite side of the road is the Dover Athletic Football Club ground and adjacent, the rugby/cricket ground. Called the Crabble Athletic Ground it was opened on Whit-Monday 1897 and neither ground are strangers to national, and once international, events.

Buckland

Dover and environs map showing the location of Buckland and Charlton and the course of the River Dour. Hasted 1798

The next village along the Dour is Buckland and although it has long since been taken over by Dover, it still retains a semblance of the village it was. The Romans laid Watling Street, the road to London along the west side of the Dour through Buckland and it crossed the Dour by a ford at the foot of Crabble Hill. The village grew up alongside this road and the Dour and extended along the valley to the west, known as Buckland Bottom. In those days, there was another Roman road that went to Richborough, probably crossing the Dour where Bridge Street bridge is today and ran up Frith Road, Old Charlton Road and east over the North Downs. North of Frith Road, there was Buckland Back Lane approximately where Barton Road and Buckland Avenue are today, joining Watling Street at the bottom of Crabble Hill. During Saxon times, the Buckland area was well inhabited, their dead being buried in a large Saxon cemetery that was discovered in the early 1950s around what is now the Hobart Crescent/Napier Road area of the Buckland housing estate. In 762AD the country’s first corn mill was recorded in the vicinity of Buckland.

At the time of the 1086 Domesday Book, the parish of Buckland was made up of the manor of Buckland, Dudmanscombe (at this time pronounced and later spelt Deadmanscombe) and Barton. The manor of Buckland was at the bottom of Crabble Hill, and was demolished in 1897 to build a tram shed (now Hollis Motors occupies the site). The Court-lodge for Dudmanscoombe and Barton was at Coombe Farm, which lay at the furthest end of Coombe Valley, where a road ran to Poulton and St Radigund’s Abbey. Buckland corn mill, was on the east side of the Dour and the mill lands, called Brox-Ditch meadow then Brook-Ditch Meadow, were along the east bank of the Dour where Lorne Road and Alfred Road are today. By 1451, the Buckland corn mill was run by Dionisia Ive and was in the hands of the Brethren of the Maison Dieu and subsequently Dover Priory until the Dissolution of Monasteries in 1535. The valley to Coombe Farm, up until the mid-twentieth century, was called Buckland Bottom and was not inhabited except for the farm. On the south side of the Buckland Bottom was an ancient cart track over Whinless Down (so called after Whinless, the old name for gorse) to West Hougham.

Hardings Brewery formerly lower Buckland corn and then paper mill 1862 painted James A Tucker c 1910. Dover Museum

By 1753 the road, from the bottom of Tower Hamlets Road where the Dover town boundary ended, to Barham Downs, south of Canterbury, was turnpiked. A toll house on Crabble Hill was built to catch folk leaving Dover by Buckland Back Lane. The toll road charges paid for road improvements and the brick Buckland bridge was built on the site of the ford using tollgate money in 1795. About four years later the nearby Bull Inn opened and is still popular today.

Up until the opening of the turnpike, papermaking was a cottage industry but following the road being turnpiked Henry Paine built a paper mill alongside the ancient corn mill. Although subjected to the vicissitudes of the economy the mill expanded and William Kingsford junior built cottages for his workers. Many are still standing today along the London Road near the Bull Inn. The Buckland (lower) paper mill became a brewery, the name changing to Hardings. This was demolished in 1962 to make way for a new Gheysen’s toy factory and then became a P&O training centre. It is, at the time of writing, a derelict site.

A water-pumping windmill was built in 1798 on the corner of London Road and Buckland Bottom. In the 1820s, Flavius Josephus Kingsford (circa 1758-1851), a farmer and miller on Bulwark Hill, above the Pier District on Western Heights, bought it. He gave the windmill site to his younger son, Alfred (1803-1878) and for himself he built Ivy House next door, 226-227 London Road and now converted into maisonettes, as his home. In 1829 Flavius and Alfred converted the windmill machinery to pump water and Alfred opened a brewery. The brewery lasted until 1889, having been taken over by George Beer and Ridgen two years before. In 1896, George Sacre Palmer (1843-1905) opened a coach building factory on the site and had a distinctive arch built over the entrance at the corner of London Road/Union Road – a replica of which can now be seen at the Transport Museum, Whitfield. Opposite the brewery, in1814, William Kingsford senior bought Buckland corn mill and the adjacent lands from Sir Thomas Hyde Page, the Western Heights Military Engineer. It was Page who built the still standing 110, London Road and the original Lorne Road bridge across the Dour.

Buckland Corn Mill Water wheel, Lorne Road. Alan Sencicle

William Kingsford rebuilt the corn mill laying the foundations of the mill we see today and Lundy House (now Ryder House), next door. By 1843 the mill was rented by Wilsher Mannering but he died ten years later. In 1865, the mill was bought by Wiltshire’s son of the same name who had set his sights on the rapidly expanding London market, sending his flour there by sea in hoys. His brother John joined Wilsher and the mill was increased to the five-storey corn mill we see today. The Mannering brothers were joined in the business by Wiltshire’s two sons and the mill stayed within the family until it closed in 1957. Following its closure Buckland corn mill was used by businessmen for offices and storage. In 1996, it was offered for sale and has now been converted into flats.

A prominent feature close to Buckland bridge is the carcass of what was the Wiggins Teape Buckland paper mill that suddenly closed in 2000. What is left of the building is an attribute to industrial architecture with a grand clock tower that still stands. The whole site extends northwards from Buckland bridge up Crabble Hill almost to where the Dover – Deal railway line passes over the London Road. On the west side of the derelict mill is the ancient St Andrews Church with the river Dour passing beneath what is left of the mill nearby.

Buckland Paper Mill c1910. Dover Museum

Originally, a corn mill stood on the site, but by 1777 it had been converted into a paper mill. Having been rebuilt and expanded several times – on each occasion following devastating fires – and also having changed hands. In 1890 it was bought by the giant paper manufacturer, Wiggins, Teape, Carter and Barlow of London, to produce Conqueror Paper. Not long after, they bought the nearby Crabble Paper Mill and for 100 years appeared to be successful up until the sudden unexpected closure.

On the west side of the London Road, from 1141 to the Dissolution of the Monasteries, was the large St Bartholomew’s Leper Hospital. The 130acre site stretched from approximately opposite what is now Beaconsfield Road to where the TA centre is these days. When it was forcibly closed, the site was sold, the buildings demolished and the land used for farming. By 1825 the site was owned by William Kingsford and that year the first houses were built there. Nine years later in 1834, Kingsford, who had over reached himself was declared bankrupt and the entire 130acre site was sold. At the time, the area was called Chapel Mount and subsequently became known as High Meadows and then Shooters Hill and over the next few decades the area was covered in housing.

In 1835 the boundary of the Borough of Dover was extended to include parts of Buckland village and immediately to the south of the then Buckland Bottom was, Dudmanscombe farm house. This was demolished and George Street, Erith Street and Victoria Street were built. At the back of the farmhouse there was a brickfield owned by John Finnis and farmlands.

Buckland Hospital c1950. Anglo-Canadian Trade Press

A large part of the lands were already owned by George Hatton Loud who owned 110, London Road. He sold part of these land holdings where the Union Workhouse was then built. In consequence, the name of the road was changed to Union Road in 1865. At the start of World War II (1939-1945) the old Workhouse was already being used as an annex to the Royal Victoria Hospital on the High Street when it was commandeered as a military hospital. In 1948, with the introduction of the National Health Service it became Buckland Hospital and the name of the road was changed to Coombe Valley Road. The building has since closed.

The still standing, York House opposite what is now Beaconsfield Road, was built by Anthony Freeman Payn, who ran the York Hotel on the Esplanade, near the Clock Tower, about 1835. Beaconsfield Road was planned in 1866 along with Churchill Street and Granville Street but they were not built until 1880. Beaconsfield Road followed the line of an ancient footpath going to Barton Back Lane crossing the Dour on planks. There was once an extensive meadow alongside the west bank of the Dour almost from Ladywell to Cherry Tree Avenue – then called Cherry Lane. The northern end, between Beaconsfield Road and Cherry Lane, had become the town’s cricket ground but in 1896, the land was sold to build housing along Millais and Leighton Roads.

By 1845, William Batchellor tells us that, ‘there is an almost continuous line of buildings (uniting) this village to that of Charlton, and to the town of Dover.’ The construction of the London, Chatham and Dover railway line in 1861, from Dover to Canterbury, required the building of a 660 feet tunnel under Shooters Hill to Tower Hamlets and two bridges over Buckland Bottom and St Radigunds Road. As soon as the railway opened, the Dover Gas Company selected a spot just west of the line along Buckland Bottom, and by 1871 they had opened their gas works there.

St Andrew’s Church, Buckland. Alan Sencicle

Around this time Edgar Road, Prospect Place, Randolph Road, Magdala Road, Primrose Road, MacDonald Road, Lambton Road a line of houses on the south side of St Radigunds Road, Oswald Road and Eric Road were built. In 1894, William Pritchard aged 8, died after falling some 14feet from the unfenced Buckland Terrace onto the London Road below. William’s death was far from being the first there. As a result the Borough Coroner, Sydenham Payn, told the council to take responsibility for fencing the Terrace. Eventually, besides the fence and the bus shelter we see today, a room with a lavatory was excavated and built into the brick wall. It was large enough to be used as an emergency air raid shelter in World War II!

St Andrew’s Church, close by Buckland bridge is Saxon in origin. Rebuilt in the 12th century, it retained much of its Saxon design and again when it was expanded in the 14th century. To meet the needs of the growing parish, in 1880, it was decided to double the length of the nave and to add a new belfry. This, however, meant the more than 1,000-year-old yew tree in the churchyard had to be moved. Supporting the roots, as they became exposed, a deep trench was dug around the base of the tree and rollers place underneath it. Reputed to have weighed 56-tons, the tree was moved in a cart along timber rails, some 60 feet to the west, where it was replanted. It survived, thrived and still can be seen today in the churchyard!

Buckland School on London Road. Opened 1859, closed in 1968 and eventually converted into a housing complex. Bob Hollingsbee Collection

Buckland had its own parochial school that opened in 1839 on the western end of the churchyard. As the population of the village increased, the school moved twice to larger premises. Then land was obtained on London Road and on 24 February 1859, the foundation stone was laid. During the excavation for the foundations of the new school Roman pottery and artefacts were found. The bell for the new school came from the sailing ship Earl of Eglinton, which was wrecked off St Margaret’s Bay in 1860 and at the same time Brookfield House, by the Dour in what became Brookfield Place, was built as a master’s residence.

On 22 May 1885, Mary Tyler, the eldest daughter of the Market Square furniture shop owner, George Flashman, laid the foundation stone for the extension of the School with George contributing £225. However, the successful school was closed in 1968 and became a social club for the staff of the cross-Channel shipping company, Townsend. Following the change of ownership of Townsend Thoresen in 1987, the former school became Churchill’s Snooker Club before eventually being turned into a residential complex.

Charlton

The last village the river Dour goes through before reaching Dover is Charlton. These days the village is hard to distinguish from its northern neighbour Buckland and the town of Dover to the south. One of the clearest indicators of the old village, but not its boundaries, is the main road out of Dover. From the Bridge Street/Tower Hamlets Road traffic lights, to the north is London Road, Buckland and to the south is the High Street which becomes Biggin Street at the Ladywell junction. This was Charlton village High Street. Another indicator is Charlton school and SSPeter and Paul Church, the latter of which is situated close by the east bank of the Dour close to Charlton Green. The Green, for over a thousand years was the centre of the old village but not long ago a large part was renamed the Castleton Shopping Centre. The River Dour is buried in a culvert under its car park!

Charlton from Priory Hill. Alan Sencicle

From archaeological evidence, there is reason to believe the Dour, in Roman times was navigable up to Charlton. By the time of Edward the Confessor (1042-1066) the manor of Charlton was attached to the Barony of Chilham, some six miles the other side of Canterbury. This was because King was one of the prebends of the ancient monastery of St Martin-le-Grand that stood near Dover’s Market Square, and his possessions included Chilham. After the Norman Conquest, Charlton continued to belong to St Martin’s monastery and then Dover Priory. About this time, above the village to the east where the hills rise towards Dover Castle on a wide relatively flat area the knights from the Castle practiced chivalry. Called Knights Bottom, the area was later integrated into the cemeteries and Connaught Park. As time passed, a mill was erected close by the west side of the Dour and in 1203 the land on the east side was given to the Maison Dieu. By by 1291, the parish Church dedicated to SS Peter and Paul had been built. Nearby was a large village green and the village grew around the Church, the Green and on both sides of the Dour. In Edward II (1307-1327) reign, it was given to Bartholomew de Badlesmere (1275-1322) and together with Charlton Green and the farmland, remained in possession of the Badlesmere family up until the Reformation (1529-1536).

Following the Reformation, Charlton Green became a separate entity to the Church and long before the turn of the 19th century, the High Street, which was part of the main concourse out of Dover, had been developed. On the Charlton side of the present day Bridge Street, St Mary’s Poor House had been built. The Green was surrounded by cottages and nearby were two mills. The land at Charlton was rich from the flood plains of the Dour and, in particular, the cottage dwellers along the High Street who all had very long gardens, utilised this. Becoming professional market gardeners, tulips grown in Charlton-by-Dover were highly prized. In the summer, awnings to maintain production covered the tulips and the gardeners also cultivated fragrant flowers from which honey was produced. Again, this was sort after by the high society of London.

Charlton Green – Chitty’s Flour Mill c 1920 – Hollingsbee collection Dover Museum

The mill opposite the Church on the Dour had existed since Saxon times but was demolished in 1850 and a new flour mill built. This was owned by the Dover Aerated Bread Company until they went into liquidation in 1865. George Chitty bought the mill, retaining the name Aerated Bread Company, but supplemented the River Dour water wheel with a 200 horsepower steam engine. For this a water tower was built to feed the boilers. With modifications to both the mill and their products the firm was so successful that they largely rebuilt the mill in 1906 and opened warehouses at Granville Dock. However, during World War II the water tower was used as a target by enemy guns and on 2 September 1944, a shell exploded on the roof and a hot piece of shrapnel lodged in the roof timbers and smouldered. By the time the fire brigade arrived, the roof was well alight. The mill never re-opened but the company was still in business for quite a long time after.

During the late 18th century, Charlton became a fashionable waterhole due to a chalybeate spring, which runs into a tributary and then into the Dour from the appropriately named Branch Street. This was successfully utilised in the 19th century, by Stephen Elms who established an aerated waters and sweet factory. In 1830 Spring Gardens, named after the chalybeate spring, along with nearby Peter Street and Churchill Terrace, were built for paper makers from Charlton Paper Mill.

Charlton Shopping Centre, High Street. LS

The mill was established in 1833, by George Dickinson, the younger brother of the famous paper maker, on the southern end of what was Wood’s Meadow. This once covered the west bank of the Dour from Cherry Tree Avenue almost to Ladywell. Adjacent to this mill, Dickinson built a large mansion that he named Brook House – which is often confused with the Brook House on Maison Dieu Road that was notoriously demolished by Dover District Council. In 1856, William Crundall senior bought the mill for use as a sawmill and over the next 100years the firm expanded along both sides of the Dour. When the company was sold the original Charlton Paper Mill was demolished. Since then houses and the Charlton Shopping Centre occupy the site.

In 1829, the bridge on Bridge Street was built and about the same time, the original Admiral Harvey Inn opened. This was on the same site as the pub of the same name now stands. Nearer to where the High Street and London Road meets, the border between Charlton and Buckland veers north and Matthew Place, Paul’s Place and Harvieian Place were built. On the opposite side of Bridge Street on the site of the St Mary’s Poor House, Catherine’s Place, Colebran Street, Brook Street and Branch Street had been built. Along Charlton High Street, the old market garden industry was giving way to retail and most of the present day shop fronts were built on the old gardens. On the west side of the High Street, without any authorisation, Barwick Alley was built in 1823. In 1842, the Alley was the centre of a smallpox outbreak and in 1875; it was condemned but was not demolished until 1882.

Former Royal Victoria Hospital, High Street. LS 2013

The whole of Charlton was incorporated into the Borough of Dover in 1836 and in May 1840, the plant and the building materials of Charlton paper mill were sold. The adjacent Brook House and half an acre of the nearby Woods Meadow were let. Brook House was offered for sale by auction in 1850 and was bought for £1,336 by the town. Following modifications, it opened as the town’s hospital on 1 May 1851 and in 1858 the part of Woods Meadow was purchased to extend the hospital. Eventually, the hospital was renamed the Royal Victoria Hospital. Maison Dieu Place was built facing the northern side of the Hospital at about the same time as Wood Street and the Dourside Cottages in 1860.

On the opposite side of the High Street, Victoria Crescent had been built in 1838 and originally was more crescent like, but the outer ‘horns’ were demolished along with the ornamental garden, to widen the High Street. About 1843, on land the town side opposite the Maison Dieu – the then Town Hall – and Priory Hill, St Martin’s Terrace was built. While on the land between Priory Hill and Victoria Crescent a similar row of houses were erected. These were demolished in 1899 in order to widen the High Street.

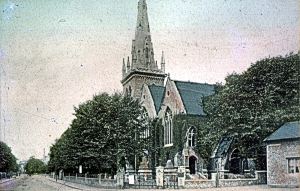

St Columba Congregational Church was built of Kentish rag faced with Corsham stone on the land that remained. With a tower some 80feet high that was finished above the roof level with Corsham stone, it was generally described as magnificent. The main entrance was described as being enriched with a wealth of sculptured stonework surmounted by a fine Gothic window. It had cost £9,000 to build and opened in September 1904.

St Columba Congregational Church, High Street, Charlton on opening September 1904. Dover Library

One hundred years later, after becoming redundant, the Church was sold to a property developer who was converting the building into luxury flats. In September 2007 the former Church was subject to an arson attack. The totally gutted remains still stand at the time of writing. It was in Peter Street that the Primitive Methodists were to build their first Chapel, which opened in 1860 but closed with the opening of the London Road Methodist Church, on Beaconsfield Road in 1901. In recent years the Methodist and the Congregationalist members joined to form the Beacon Church utilising the former London Road Methodist Church. It was this that led to the closure of St Columba Church.

Maison Dieu Road was originally called Charlton Back Lane and this was/is on the east side of the River. Opposite, on the west side, between the Lane and the Dour, was Maison Dieu Park. During the 19th Century they were both developed for housing with the building on Dour Street starting in 1862, parallel to the Dour. Between Dour Street and the river was Alfred Matthews building yard but this was destroyed by fire in 1874. Subsequently the land was incorporated into the Crundall sawing mill complex in the opposite side of the Dour.

By all accounts, Charlton Fair was one of the most popular fairs in the neighbourhood but as developers needed more land the Fair diminished in size and about 1850 moved to Barton Meadow, close to the River Dour, on the west side of Buckland Back Lane. Following the move, Anthony Lewis Thomas started a jobbing foundry on Charlton Green, which continued after his death in 1878. By this time the expanding foundry was named AL Thomas & Sons that specialised in manhole covers and street lamps. In 1902 it became a limited company and by 1908, Dover Mayor, Walter Emden, owned a controlling number of ordinary shares in the company and put his nephew, Vivian Elkington, in charge.

Renamed Dover Engineering Works Ltd, during World War I the company was responsible for maintaining the two-hundred-strong fleet of the Dover Patrol. When peace returned work resumed making manhole covers and lampposts but due to the increasing number of motor vehicles there was a demand for stronger and better fitting covers. After experiments, in 1928 Elkington and his foreman developed what became the well-known Gatic Cover (Gas & Air Tight Inspection Cover). During World War II the Engineering Works moved to Watford but agreed to come back to Dover if they could used their old premises on Charlton Green.

Dover Engineering Works, Charlton Green.

Initially, they opened a small foundry within the Eastern Dockyard while the Charlton foundry was rebuilt. Culverting the once famous chalybeate spring to flow into the Dour near what is now Charlton multi-storey car park, the new premises included the area previously occupied by the lower end of Peter Street and Spring Gardens.

The new foundry meant that the company could expand operations to included large projects for airfields, power stations and oil installations. In 1964, at the height of the Engineering Works success Vivian Elkington died aged 82. The Company became a subsidiary of Newman Industries, Bristol, in 1977, then eleven years later, in July 1988, they called in the Receiver. Bought by the Parkfield Group, most of the foundry work moved to Irvine in Scotland. Some production did move to Coombe Valley Road but only 23 out of the 155 jobs were saved.

River Dour at Charlton Green, the gated garden next to Morrisons in on the left. Halfords can just be seen with the Red Lion pub on the right. 2014. LS

The Charlton Green engineering complex was demolished and a B&Q superstore and car park was built on the site. Later joined, in October 1990, by a Co-op Leo £7.5m food super-store with its own car park under which the remaining exposed River Dour at Charlton Green was culverted. The next door Charlton Centre and its car park were sold to Targetfellow, a commercial property group in 2006 though the Co-op had closed its doors at Christmas in 2004. The previous Co-op building was divided into smaller units and renamed the Castleton Shopping Centre so as not to be confused with the Charlton Centre next door. In 2009 B&Q moved to a much larger store on the Whitfield trading estate and on 25 January 2010 Morrisons supermarket opened its doors on the former B&Q site. The adjacent land that was left of the once extensive Charlton Green, next to the Dour and close to Bridge Street bridge, was cleaned up and became a gated picnic area.

Up until 1881 there was a ford through the Dour by the north side of Charlton Church and with the building of Brookfield Road it was replaced by a footbridge. In 1902, following the building of properties on Beaconsfield Avenue, the footbridge was demolished and the road bridge we see today was built to connect the two Beaconfields. World War II took its toll on much of Dover and in 1947 the 53-year-old London Fancy Box Company moved into the war damaged former Chitty flour mill on Bridge Street. They had come to Dover as the War had created a shortage of female labour in London.

The London Fancy Box Company had a new factory built on Beaconsfield Road and Granville Street, by the side of the Dour, and in 1953, the firm moved in. The former Chitty flour mill was taken over by Dover Engineering Works, demolished and new works built. The London Fancy Box Company thrived at Beaconsfield Road and opened another factory in Coombe Valley Road. An exhibition was held at Dover Museum, in 1994, to celebrate the firm’s centenary, but it had already become heavily automated and in 1998 the Beaconsfield Road factory closed. The factory was demolished and properties were built, the site of the Dover Engineering annex – formerly Chitty flour mill – was taken over by Halfords motor accessories in 1989.

St Peter & St Paul Church, Charlton. Alan Sencicle

Charlton’s SS Peter and Paul Church was expanded in 1827 and again in 1847 to meet the growth in population. To quench their thirst, the nearby ancient Red Lion Inn was rebuilt about 1843! In 1891, J J Wise of Deal rebuilt Charlton Church to a cruciform design in stone, by James Brooks (1825-1901). In the early English style, the Church has a central fleche with one bell and seating for 700. The old Church, on the banks of the Dour, was later demolished and Barton Riverside Path, which had been laid between Cherry Tree Avenue and Beaconsfield Avenue was extended from across the Avenue to Frith Road forming the pleasant public walk that still exists today.

Charlton Primary School, Barton Road. Alan Sencicle

Charlton’s children were without any form of education until Rev. Frederick Augustus Glover (1800-1881) was appointed rector of the Church (1837-1845). A keen mathematician he registered with the Patent Office the specification of an ‘improved instrument for measuring of angles.’ In 1840, Rev. Glover instigated the building of the first parochial school for Charlton; this was for 80 boys and was situated in the churchyard. In 1875, a new boys’ school was built on Granville Street and a girls school was started in January 1877 on Buckland Back Road. Having possibly been taught in the Granville Street school, the girls along with infants, on 2 June 1882 moved in to their new school and this we see today on the later renamed Barton Road corner with Frith Road. On Wednesday 13 September 1944, during World War II, the boys’ Granville Street school was destroyed by enemy action. To accommodate the Boys, an extension was added to the girls’ school in 1954.

Barton Farm was east of Charlton Church on Buckland Back Lane and from the 1880s farmland was being offered for sale for property development. The land immediately next to the Dour was acquired for the Cherry Tree Avenue – Beaconsfield Avenue, Dour side walk. By 1900, Barton farmhouse had been demolished and Charlton Avenue, Limes Road and Barton Grove were built on the site. Further developments took place along the newly named Barton Road and Heathfield Avenue and Mayfield Avenue were developed across the hillside on the east side.

Barton Farm on the River Dour, glass slide not dated. Dover Museum

Traversing these roads down to Barton Road more roads laid out to housing were built. Access to Long Hill, high on the east side of the valley, had been created by the London, Chatham and Dover/South Eastern Railways when they built the Dover-Deal railway line. It was an ancient right of way from Buckland Back Road to the Roman Road that eventually went to Richborough. Astley Avenue, named after Dr Edward Farrant Astley, was built in line with this footpath and on Long Hill, Dover Marquee Company moved their business just beyond the little tunnel on Long Hill where the Corporation also laid out allotments.

Barton Road School LS 2013

To meet the spiritual needs of the influx of new residents, St Barnabas Church was built in 1901 on Barton Meadow near to Cherry Tree Avenue. However, in 1940 the Church was badly damaged in and air raid and demolished. Barton Road Elementary School opened next to St Barnabas Church in January 1903 and alongside the Barton riverside path. Separate infant accommodation was started at about the same time and the girls’ school was built in 1912 on the same site. In 1937, Shatterlocks Boys’ School, on Heathfield Avenue, opened and eventually became a mixed infant school and Barton Infant School closed. Following the World War II up until 1957, when Archers Court Secondary School opened at Whitfield , the school catered for children between 7 and 15. That year Barton School became a junior school.

Ecological Plight of the River Dour since World War II

From this brief look at the history of the development of the villages along the Dour it can be seen that over the last 200 years the river has sustained numerous industries and from Buckland onwards, extensive housing developments. The industries that have utilised the diminutive River Dour included corn and paper mills, breweries, tanneries, saw mills, electricity and gas works, a pipe factory, an iron foundry and a box factory, to name but a few. In 1901, Dover Corporation sought to have the Dour recognised a river in order for them to constrain over usage and to try and keep it clean. However, the government authorities declared that it was merely a watercourse, which meant that it belonged to the owners of land on either side of the river and they could use it as they wished!

Abercrombie Plan – Planned redevelopment of Dover along the Dour c 1947. Dover Library

During World War II, both bombs and shells heavily scarred the town. When the shelling ceased on September 27th 1944, it was estimated that the war damaged sustained was proportionally greater than in any other town throughout the country. In June 1945 Town Planner, Professor Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957) was hired to produce a Reconstruction Plan for Dover. The premise of his Report was that ‘the lifeblood of a town of the nature of Dover is undoubtedly its industry,’ and this was to centre on the Dour valley. Although the Professor did emphasise the importance of the ecological and historical aspects of the Dour, the council ignored this. The overall result was that, at best, the Dour was treated as an inconvenient nuisance, ideally to be buried – most notably at Charlton Green. At worse, it was a dumping ground for household and heavier rubbish. As for the proposed redevelopment of Dover this became piecemeal with a move away from industry to housing.

The New Dover Group recommended, in 1965, to the then Dover Corporation that the Dour should be cleaned throughout its length. Adding that voluntary labour to do the job was available. They also advocated that once the Dour was cleaned up it should be turned into the town’s corridor of natural beauty. Finally, that the Barton Path should be cleaned and repaired and that a walk should be created between Kearsney Abbey and Townwall Street along the Dour. The Corporation made the right noises, Barton Path was repaired and swept but then they permitted developments along the banks of the Dour and forgot about the other recommendations.

Pencester Gardens riverside path next to the Dour. Alan Sencicle

Dover Corporation was disbanded and replaced in 1974 by Dover District Council (DDC) and the New Dover Group banged the proverbial drum in their ears over the state of the Dour. Some of the members, that year, set up the River Dour Association with the prime objective of making the river an ecological paradise and creating a walk along its banks. Although the Dour was still officially a watercourse and therefore did not have the legal status of a river on environmental issues, DDC, in the late 1980s laid the Dourside footpath in Pencester Gardens.

Although the New Dover Group had disbanded in the early 1980’s, later that decade the Dover Society was formed basing their constitution on that of the New Dover Group. Most of the members of the River Dour Association were also members of the Dover Society, whose concerns included the neglected and polluted Dour. In October 1989 the Dover Society led a major clean up of the Dour with Whitbread and Shepherd Neame breweries providing the incentive of 50 dozen cans of beer to volunteers along with funds. 115 folk from local pubs plus many others turned up and in one day, the Dour was cleared from Temple Ewell to New Bridge! The result required a fleet of DDC vehicles to clear everything away, which angered a few! Within weeks the Dour was again turning into a dump with rubbish ranging from both domestic and industrial waste and appliances to abandoned vehicles, furniture and furnishings.

The River Dour Association public meeting, called over the poor state of the Dour held in Biggin Hall 18 January 1991

By the early 1990s DDC spent over £22million pounds on the ill fated White Cliffs Experience in the Market Square and associated projects and the River Dour Association were angry. For except the show piece of Pencester Gardens, the remainder of the Dour was totally neglected and they called a public meeting. This took place on 18 January 1991 in Biggin Hall and was so well attended that folk were standing in the aisles!

The clean up began and by the beginning of May the Dover Society were again demanding a riverside walk from Kearsney Abbey to the Seafront. However, this proposal led to a proliferation of objections from residents along the proposed route, so the notion was abandoned by DDC. By the end of that month, Southern Water applied to dispose of screened sewerage in the Dour at Wood Street, by the Charlton Centre, and a month later the National Rivers Authority applied to abstract water from the Dour nearer its source.

Complaints by ‘namby, pamby conservationists‘, as they were called by Councillors, Council Officers and vociferous members of the public, led to government officials arriving in Dover. They came in October 1992 with the remit to check if the Dour really had any ecological problems of concern. They were made welcome by those who insisted there were no problems and were shown the Dour where it runs through Pencester Gardens. However, the officials returned and carried out their own observations and testing.

Their report, in essence, stated that they were shocked at the state of the Dour adding that something should be done quickly. By December the White Cliffs Countryside Project (Later White Cliffs Countryside Partnership) were given authority to look into the state of the Dour and the Kent County Council (KCC)/DDC IMPACT joint committee agreed to make the riverside walk proposal a primary objective. Albeit, in May 1993, KCC sold land fronting the Dour near Cherry Tree Avenue to a firm of car breakers and DDC apparently due to financial constraints, was finding funding difficult. Then, in December 1993 came the good news, after 92 years of petitioning the Environmental Agency officially upgraded the Dour from a watercourse to a river!

Dour Path alongside the river Dour , Maison Dieu Gardens. LS

Nonetheless, problems and rubbish continued to increase such that various volunteer groups set aside whole days to clean the Dour and the River Dour Association became River Watch headed by Ian Lilford of Balfour Road. Sustained success started to be achieved and in January 1998 the Dour was upgraded from a stream to a river! The little bridge on the Maison Dieu path alongside the Dour between Maison Dieu gardens and South Kent College, was replaced in 2001 by the College and DDC. The path was also re-laid. River Watch were able to report that there was significantly less dumping of household goods in the Dour but that litter was still a problem. On undertaking a check on the ecology of the Dour, Environmental Agency inspectors, using stun equipment, found that the Dour had a significant level of brown trout and that they were successfully breeding in the lower reaches.

In January 2004 Dover Town Council (DTC), formed in 1996, officially recognised that the River Dour had the potential to become an asset to the town! Albeit, not quite in the way conservationists envisaged for by April that year they were giving consideration to installing wind turbines along the River. This was to produce electricity but the notion came to nothing. Meanwhile, River Watch volunteers continued to try and keep the Dour free from rubbish and litter, loudly suggesting that a full-time warden be employed to stop the river being used as a ‘public dustbin.’ DTC responded, pleading a lack of money.

White Cliffs Countryside, River Dour Path Trail White Cliffs Countryside Partnership

Not long after, River Watch ceased to exist as a Group. Then, in November 2006 a Wild Life Trail along the banks of the Dour was launched by the White Cliffs Countryside Partnership. Nonetheless, the problem of rubbish and litter never seemed to lessen and in 2007 the Dover Society set up their River Dour Steering Group, in an effort to try and keep on top of the problem. In the spring of 2013, DTC installed five information panels along the banks of the Dour, by local artist and researcher, Anita Luckett. These panels tell the story of the Dour and its wildlife.

Although the cleaning up of the Dour has come a long way since the 1960s, there is still some way to go, particularly in persuading folk to appreciate and care for the Dour. This includes telling folk that it is not a rubbish dump, nor are the brown trout and mallard ducks, which now breed in the lower reaches, to be taken home for supper! The White Cliffs Countryside Partnership’s well signposted trail along the Dour is the basic theme of Part II of the story of the River Dour.

Presented: 3 June 2016