The distinctive East Kent Road Car Company logo that was agreed in the summer of 1916

Part 1 of the East Kent Road Car Company (EKRCC) story covered the growth of the firm from its inception in 1916 to the end of World War II (1939-1945), in relation to Dover. By the end of the War EKRCC was short of vehicles as all of its garages had come under varying degrees of enemy attack. The greatest loss of EKRCC’s employees lives had occurred in Dover when the Company garage on Russell Street was bombed in 1942. From then on, much of EKRCC’s operations within the town were run from the bombed out Russell Street garage and an old bus parked on a bombsite in Pencester Road. Thus, EKRCC was faced with the massive financial costs of purchasing new and replacement buses as well as major building works. This strain was seen when due to demobilisation of the forces in 1945, the number of passengers carried by EKRCC was just under 60million!

Castle Street following the last shell to hit Dover on Tuesday 26 September 1944. Kent Messenger. Dover Library

Further, not only was there a national shortage of materials, which increased costs, after taxes and working expenses the company were obliged to pay Dover Corporation 75% of the income earned from within the town’s boundaries. This was the result of the contract drawn up in 1936 when EKRCC took over the town’s public transport. As Dover was facing colossal problems due to 4 years of continual bombardment, the money was badly needed. In 1944-1945 this amounted to £11,148, which would have bought at least three new buses. At the outset of the War, in 1939, Dover was designated Fortress Dover and came under military rule which imposed travel restrictions. Once the fear of shelling, bombing and V2’s had passed in late 1944, the pre-war bus services started to be reintroduced. The first was the Sunday morning service that enable people to go to Church.

In 1946, for the first time since early 1940, people came to East Kent on holiday and J B Chevalier succeeded F W Saltwood as Traffic Manager of EKRCC. In February that year Chevalier introduced a regular service from Victoria coach station, London that proved a greater success than envisaged. The influx of tourists that summer was appreciated by East Kent’s holiday industry but resulted in long queues at bus stops due to the shortage of vehicles. The chairman of EKRCC and also the founder of the company, paternalistic businessman Sidney Emile Garcke (1885–1948) announced that the company’s basic obligation was to ensured workers were not too delayed. He therefore made available special priority tickets for those going to and from paid employment.

Under Garcke’s direction, female drivers had been introduced during the War as well as conductresses on the same terms, conditions and wages as men. However, following the War, male workers returning from the Front were looking for jobs so the policy was proving controversial. It was agreed with the Unions to retain the existing females but the drivers were to be replaced by men. The women’s wages could be up to 75% of the men’s wage for the same job. Traditionally, men were seen as the breadwinners while women’s wages paid for the family ‘extras’. Although some of the women were widows who had lost their husbands during the War, it was said that they received widows’ pension, which would make up the difference. The main Union representing bus workers was the Transport and General Workers Union (T&GWU).

East Kent Road Car Company Russell Street garage Dover following bombing on 23 March 1942. Dover Museum

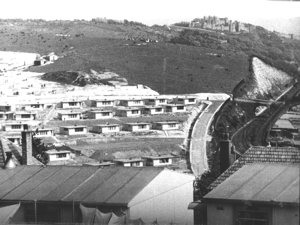

Although EKRCC were faced with great expense to meet the bus company’s needs and the demands being placed on it, these paled against the tasks and expense facing Dover Corporation. Beside the destruction of the EKRCC garage and the building that housed the bus company’s pre-war offices in the Market Square, 957 homes had been destroyed; a further 898 homes had been seriously damaged but remained inhabited and 6,705 houses were less seriously damaged and habitable. Public, general business and industrial premises were in a general poor state with most suffering various degrees of devastation. In 1944 the Council had applied for powers to build 400 temporary houses, 178 permanent, and rebuilding 41 war-damaged dwellings.

During the intervening period, they had sought the advice of Professor Patrick Abercrombie (1879-1957) in planning for the future of the war battered town. His recommendations included the suggestion that the southern end of the town would be the main shopping and recreation area – where the present (2016) proposed St James shopping precinct is envisaged to be located! As, Abercrombie stated, it would be ‘undisturbed by other than local traffic and within easy reach of the Omnibus Garage and Station and the service routes.’ This, of course, was a long time before the present A20 was built.

Abercrombie Plan – Planned post-war redevelopment of Dover c1947. Dover Library

Professor Abercrombie did not specify the location of the bus garage nor the proposed bus station but the assumption was that the garage would be on the pre-war site facing Russell Street and the bus station at the northern end of the shopping/recreation area. Number 10 Pencester Road, a shell damaged house on the north side of Pencester Road, had not long before been acquired by EKRCC. Therefore it was presumed Pencester Road would be the locality of the bus station. Specifically, Abercrombie’s report stated that industry was to be located at the Eastern Dockyard and north of the shopping/recreation area at Charlton along the Dour valley. The loss of homes was to be met with large housing estates on the hillsides of Aycliffe, St Radigunds within the Coombe Valley, Temple Ewell and on the former Old Park estate on the eastern slopes of Buckland.

Before the Professor was appointed, Dover Corporation had drawn up similar plans but ratification by such an eminent personage as Abercrombie was needed to provide influence on permissions and, more importantly, government grants. Following the publication of the Report, the council compulsory purchased 198 acres of the Old Park Estate and erected 480 pre-fabricated ‘temporary’ homes or Prefabs as they were called. For churlish reasons (see Old Park part II), the Old Park land was renamed the Green Lane Housing Estate and it was only as it developed, the area became known as the Buckland Estate. Abercrombie had emphasised, in order for the plan to work it relied on an adequate and efficient bus service. With this leverage, Dover Corporation entered into discussions with the vehicle strapped EKRCC, an agreement being reached whereby the tramlines that had been scheduled to be removed before that War would be taken up from Buckland Bridge to Cherry Tree Avenue and the road resurfaced. At the same time the entrance to Union Road, now Coombe Valley Road, would be improved to allow buses easier access.

At the end of 1946 Sidney Garcke stepped down as chairman of the EKRCC, a position he had held for 29 years, but he retained his seat on the Board until his death in October 1948. Alfred Baynton, who had been both the General Manager and Company Secretary of EKRCC since its inception, retired and was succeeded by R G James, Manager of the Devon General Omnibus Company as General Manager and B D Stanley became the Company Secretary. Stanley, like Baynton had been a shareholder of the company from 1916 as was Raymond Percival Beddow (1903-1981), who was appointed Chairman. On taking over, Chairman Beddow told shareholders that in December 1946, the company had just over 420 vehicles in stock – not all of them would have been licensed to operate but this was not mentioned. However, Chairman Beddow did say an order had been placed in September for 160 new vehicles.

East Kent Road Car Company service 90, Dover – Folkestone, 53-seater Leyland PD1 with Leyland body work. Dover Museum.

Of the 160 buses ordered, 50 were Leyland Tiger PS1 (P=passenger S= single deck) single-deck coaches and 60 were Dennis Lancet single-deck buses, all with Park Royal of London, bodies. The latter were supplemented by a further 12 arriving in 1948 while the remaining 50 were Leyland Titan PD1’s (P=passenger, D=double-deck) double-decks. 49 were PD1As and the remaining one a PD2/1 but all having Leyland lowbridge bodies. However, due to shortages of materials at the factories, the buses did not start to arrive until October 1946, first 12 of the Lancets did not arrive until 1948 and the 160th bus did not arrive until 1949. The total mileage of the company’s buses up to the end of 1946 was 13million miles about 3.5million miles more than the year before.

At the time, the Nationalisation of the Railways bill was going through Parliament and this came into force on 1 January 1948. Southern Railway had a large shareholding in EKRCC and when it became Southern Region, that shareholding was retained. At the same time, the government’s Transport Bill proposed the setting up of the Transport Commission with the power to acquire passenger road transport undertakings under schemes promoted by the British Transport Commission (BTC). This was for the co-ordination of transport in a particular area, which could justify the nationalisation of a bus company. EKRCC and its parent company, British Electric Traction Company (BETC), unanimously objected to such a take over. The retired Baynton gave evidence to a Parliamentry Committee, on their behalf. Baynton based his argument on the one given by Garcke back in 1928 (see EKRCC story Part I), and went on to say that this had been taken on board in the subsequent legislation and together with the Road Traffic Act of 1930, the public was adequately protected. In consequence, neither company Baynton represented were taken over by BTC.

However, a contemporary company to BETC, Tilling Motor Services, had sold out in September 1948 for £25million as its majority shareholdings were held by pre-nationalised railway companies. Thomas Tilling (1825-1893) had set up the London passenger transport firm and by 1850 it was one of the largest such services in the Capital and particularly noted for good time keeping. His sons, Richard and Edward joined the firm and in 1897 it was incorporated as Thomas Tilling Ltd (TTL). They had formed the Folkestone and District Car Company, which was one of the original firms that created EKRCC and by 1928, TTL had interests in 11 regional bus companies. These, like all of the other Tilling assets, were nationalised.

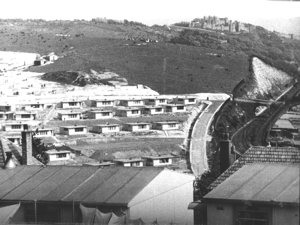

Prefabs on the developing Buckland Estate late 1940s. The railway track on the right is the Dover-Deal line. Dover Museum

In January 1946 EKRCC, having lost its headquarters in Canterbury to enemy action, acquired Odsal House at Harbledown, for use as temporary headquarters. At about the same time the rebuilding of the war damaged St Stephen’s body and paint shops in Canterbury was started. Due to shortage of materials the buildings were not finished until 1948. On 21 May 1947, the bus service to the new prefab estate on what became the Buckland Housing Estate in Dover was started. The roads had been named after places in the U.S.A. which had sent food parcels and also places in the British Commonwealth that had helped the country during the War. The following year, the Olympic Torch arrived in Dover from France aboard the destroyer Bicester and huge crowds came to watch Dover Co-operative worker, Sidney Doble, carrying the torch through the town and out along the London Road towards Canterbury. Crowds lined the route all the way to beyond Lydden but EKRCC ensured that buses were waiting at strategic points to take people back to stops in Dover. The company was praised for the efficiency in clearing the crowds and having them on their way home within 90minutes.

Ashridge College, Berkhamstead, Hertfordshire 1950s. EKRCC drivers went there to undertake the RSA Chartership course and exam in Transport and Operations. Ashridge Archive

Following the War, General Manager Baynton had encouraged all EKRCC staff to take courses and examinations on aspects of transport run by the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce (RSA). On passing exams the employees received diplomas and Baynton promised them that these would further their careers within the company. The take up was such that managers of EKRCC garages set up local training facilities and this, in turn, encouraged more staff to undertake the courses with some drivers going on to take advanced courses in transport operations at Ashridge College, Hertfordshire*. On successful completion, the drivers were admitted into the Chartered Institute of Transport and Logistics. Dover historian, Joe Harman was one such EKRCC bus driver. Unfortunately, Baynton’s successor was not so enthusiastic about such training and made this felt in a number of ways. This was most notable when it came to promotion when it was made clear that length of service outweighed qualifications. This not only disgruntled the qualified staff who had worked hard and in their own time to gain the qualifications, but others saw little point in making the effort. Slowly external training with qualifications ceased at Ashridge for EKRCC employees but did continue at local colleges of further education. *Of note the course and similar courses at Ashridge College led to the 1954 Ashridge Act, which drooped the affiliation with the Conservative Party and to form Ashridge Management College.

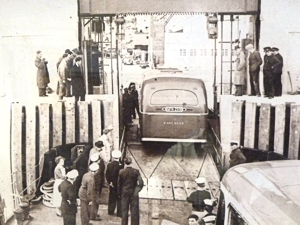

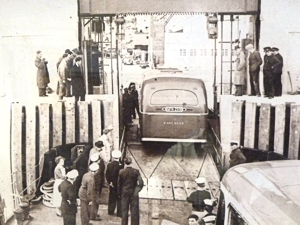

Loading an East Kent Road Car Company pre-war Leyland TD5 rebuilt as a 35 seater single decker by Beadles, aboard Townsend’s Halladale on 11 May 1953 at Eastern Dockyard trying out the new drive-on drive-off facility. Lambert Weston for DHB

Petrol rationing, which had been imposed in 1939, was lifted in May 1950 but petrol tax was increased, on average, from 35.95% to 49.65% and this cut heavily into EKRCC finances. To increase the fleet, some 24 double-deckers that had been bought in the 1930s and had seen heavy wartime activity were sent to the Eastern Coach Works at Lowestoft, where they were rebuilt as lowbridge 55 seaters. A further 35 went to the Park Royal Works in London and were also rebuilt as lowbridge 55 seaters. While, in 1951, 28 pre-war Leyland TD5s were given new chassis by Beadles of Dartford and converted into forward entrance 35 seater single-deck coaches. At least one of these was later used to test the new loading berths in 1953, at the newly built Eastern Docks, as can be seen in the photograph, the bus is being loaded onto Townsend car ferry Halladale.

In early 1949, EKRCC had launched its Inclusive Tours Department from a rented defunct Royal Air Force operations room overlooking Ramsgate Harbour. The holiday coach tours included tours of Scotland, the Yorkshire Dales, the Lake District, Cornwall & Devon and Wales. At about the same time, EKRCC ordered 25 half-cab front engined Dennis Lancet J3s for the service. That year, the weather was kind and the project a great success so in February 1950, EKRCC launched its first Continental coach tours brochure. On offer were two 14-day tours to Paris and the French Riviera, taking in Lyons, Cannes and Nice and crossing on the Halladale between Dover and Calais. The 28-seater coach (EFN 587) was craned on and off the ship both in England and France, but all went well with the tours. That is, with the exception of two ladies who wandered off during a short stop at Lyons. With the help of the Gendarmerie, the two ladies joined the coach at Calais!

East Kent Road Car Company European coach tours to Switzerland and the Austrian Tyrol advert, 1953.

The following year London Coastal Coaches, who owned Victoria Coach Station, London, handled most of the bookings and the number of EKRCC tours expanded, included two costing 44guineas to Switzerland and lasting twelve days and two costing 42guineas of 11-days duration to the Austrian Tyrol. The Company went on to work with Global Coaches, Royal Blue Coaches and in 1953 joined the European Railways’ Europabus network of international coach services. For this, they provided buses and coaches between London and Dover, where passengers to Ostend travelled on Belgian Marine ships out of Dover and linked up with services to Brussels. For this service, the EKRCC vehicles were painted light blue to match the Europabus livery. On 26 March 1951 – Easter Monday – EKRCC organised a census taken on the A20 at Charing near Ashford, Kent. It was found that in the space of 90 minutes, 65 non-EKRCC coaches were taking folk from London to either Dover through Folkestone or Thanet through Canterbury. Most of these were owned and driven by former military drivers. When the Company started to implement cut-backs, they found it profitable to hire out vehicles to these independent companies.

Looking back, this was seen as the golden era for the Company and in 1952 it boasted of 586 vehicles and had depots in Canterbury – where major maintenance took place – Dover, Deal, Folkestone, Ashford, Herne Bay, Ramsgate and Rye in Sussex. In 1951 the first underfloor-engine single-deck coaches, five Leyland Royal Tiger coaches with Park Royal bodies (FFN 448-453) had arrived. At the time, the industrial complex within the Eastern Dockyard , as advised by Professor Abercrombie in his report, was proving to be successful. To enable workers to get to and from the complex Dover Corporation created an extension of the promenade to the Dockyard gate and this included a bus turning area, a large bus shelter and public conveniences, which were completed in 1951. However, the relationship between the Corporation and Dover Harbour Board (DHB) was not good, with the latter secretly planning to take over the Dockyard for shipping.

By the end of 1949 the first of 15 x 20-seat Dennis Falcons arrived and were used to replace all of the EKRCC pre-war Dennis Aces. At the time, due to legal restrictions, these were the only vehicles in the fleet that could be used on one-man services and this did not go down well with the drivers or conductors. 80 Guy Arab III class double-deckers that had been ordered from Guy Motors of Fallings Park, Wolverhampton and started to arrive in 1950. The first (EFN170-209) were 53-seater lowbridge vehicles with Gardner 6LW engines. These were the last of this type to be bought by EKRCC. The second batch (FFN 360-399) had 56-seat highbridge bodies and also heaters – the first East Kent double-decks to be so equipped.

That year, on Wednesday 27 June 1951, Townsend’s Halladale left the Eastern Dockyard from where the Ferry Company operated. On board were a number dignitaries including EKRCC’s Chairman Beddow and his retinue plus DHB and Townsend officials as well as one of the new 8-ton single deck Leyland Royal Tiger 37-seater coaches (FFN453) and its driver. At Calais the ramp was lowered on to the rear of the ship and the bus with passengers was driven off, along the 120foot incline, without any trouble. The driver turned the bus round and successfully drove it back on board. Four days later, the Calais ramp came into operation as the first drive-on, drive-off ferry berth on this section of the English Channel. The ro-ro berths, as they are called, were an integral part of the rebuilt and renamed Eastern Docks that opened in 1953.

EKRCC Arab class 56-seat (later 58 seats) highbridge double-decker by Guy Motors of Wolverhampton. This one (908) was unique in the batch as it had a Guy body and an open platform. Vic Underhill

A further order for 30 Guy Arab IV double-deckers (GFN 908-937) were delivered in 1952 and like the Guy Arabs that had previously arrived, they were Park Royal’s highbridge with 56 seats. The front bonnet had been redesigned to conceal the radiator and they nearly all had platform doors updated with a curved front. For some odd reason one, GFN 908, had a Guy body and an open platform. That year saw the launch of the Maidstone and District and East Kent Club (M&DEKBus Club), named after the green liveried Maidstone and District Company (M&D) and the cherry red and white liveried EKRCC buses.

However, EKRCC continued to complain of financial problems. With a totally different approach, aims and objectives, the Company’s strategy was moving away from that adopted by Garcke and Baynton during their 28-year rule. At the time the company stated that out of their fleet, 220 buses were pre-war stock of which 77 had post-war bodywork and 66 were of the wartime utility vintage. Since the War the costs of raw materials had steadily risen and with them, wage increases. This combination had brought about inflation, which the government dealt with using fiscal policies such as taxation. For the years 1950 and 1951, EKRCC paid £215,000 per annum to meet tax and wage bills and in 1952 the tax and wage bill came to a further £317,000. The main tax bill was on fuel, which amounted to a 200% tax while wages had risen at an estimated 8% per annum since the end of the War.

Finally, the nationalisation of Southern Railway, a significant shareholder in the company, was taking its toll on company finances. EKRCC asked the Traffic Commission to be allowed to raise fares and in July 1951 this was eventually agreed, against opposition from passengers and the local media. A year later, EKRCC again applied for a fare increase and this was instigated on 27 October 1952. Amounting to between 2.5% and 12% the increase in fares was expected to provide an estimated £110,000 to meet costs. In the event, due to a fall in demand as folk found alternative modes of transport, the rise did not meet the outgoings, so again, the company applied for a fare increase. This was denied as being too close to the earlier fare increase and because of the dividends being paid to shareholders’, which was 10% of net income with bonuses of up to 10%!

In June 1952, Dover Corporation took issue with EKRCC over bus fares and hospital visits. Fares were charged by the mile and at the time Kent and Canterbury Hospital was the provider of specialist treatment. Bus service 15, as today, between Dover and Canterbury travelled by the then A2 that followed the route of the Roman Watling Street. As these days, the bus went through Temple Ewell, Lydden and up the steep hill to cross the North Downs to Barham. Unlike today, in those days the A2 was a single carriageway and after Barham Downs dropped sharply into the village of Bridge. On leaving Bridge it was a climb up a steep hill and then a straight road into Canterbury. The journey took approximately 55minutes but on alighting from the bus there was still a walk or another bus ride to the hospital. The fare stages made the journey expensive but seen as commensurate with the rail journey by EKRCC.

Buckland Hospital c1950 at the time Dover’s cottage hospital with inpatient beds. Anglo-Canadian Trade Press

The Royal Victoria Hospital was Dover’s General Hospital with Buckland Hospital, on the then Union now Coombe Valley Road, the annex that provided a number of services and inpatient beds. Those that had to attend Buckland Hospital for whatever reason faced the problem of expensive bus fares. The fare stages within the town were every mile and one was on Union Road at Primrose Road approximately 300yards from Buckland Hospital entrance. This meant that those who used the bus stop near the Hospital had to pay 2pence more than those who used the Primrose Road bus stop. Consequently, the fare structure hit the less able hardest! H S Price, EKRCC local Traffic Manager, promised to look into the situation and eventually the fare stage at Primrose Road was moved to Buckland Hospital. The Canterbury fare problem was not so easy to resolve as the EKRCC Board were more concerned that if the price of the fare was cut non-patients would also be eligible for cheaper fares.

November 1952, the company successfully applied for permission to recapitalise with the issue of 900,000 Ordinary £1 fully paid up shares for every two £1 shares held. While this was going on the Labour government floated a Bill to nationalise ALL public transport and in Dover there was a packed protest meeting held at Connaught Hall in the then Dover Town Hall, now the Maison Dieu. The nationalisation did not go ahead but EKRCC senior management continued to complain about the Company’s financial problems. Following accountants advice, so they said, ‘economic cut backs,’ were implemented. These centred on reducing or stopping poorly patronised services particularly in rural areas and town services, outside peak times. This enabled staff to be laid off and so both wage and fuel bills fell. Albeit, potential passengers looked to alternative methods of transport, notably bicycles, railways and ‘shanks pony’ (walking). The predictable result was a further fall in passenger demand which resulted in more cutbacks and the Company focused on the high yielding holiday traffic and cheaper ways of providing public services.

EKRCC Dennis Lancet 3 x 35 seats Park Royal bodywork bought in 1948, withdrawn in 1960, disposed following year. With Inspector John Conway at a Deal vintage show. AJ Conway

East Kent, like other eastern areas of the UK, suffered severe flooding in January 1953, with Southern Region railway lines, particularly between Faversham and Birchington, washed away. EKRCC were called upon to provide replacement services and made some 40+ buses, which had been in winter storage, with drivers available. Once the floods had subsided, the railway company and Kent County Council (KCC) hired buses with drivers to take workmen to where repairs to the railway lines and sea defences were taking place. The subsequent revenue received by EKRCC provided sufficient finance to maintain services that would otherwise have been axed. In 1956 the remaining Guy Arab double-deckers arrived and were used to replace old rolling stock. This final batch had mechanically closing doors with heating on both decks and seating for 61 passengers. A couple that had arrived in February, were given an inaugural run taking pit-workers’ children, living in Deal and Dover, to see the pantomime in Folkestone.

Elizabeth II’s Coronation Day was on 2 June and EKRCC catered for an expected huge demand for vehicles to take passengers to and from London. In realty, although the demand did increase, it was far less than expected due to the general public buying televisions to watch the event and street parties organised for the occasion. In areas where the television reception was poor, such as Dover, there were also attractive civic events organised by the councils and social groups. All were well attended.

A wet summer and a subsequent fall in holiday traffic followed the Coronation so EKRCC implemented cutbacks in public services. Staff were shunted around localities and jobs within the Company and many looked for jobs elsewhere. One of those who left was Joe Harman, who became an ambulance driver. He later wrote that although EKRCC offered him an increase in wages to stay he would have been expected to work as a shift relief at different localities. Joe wrote that at about this time he had a routine x-ray – between 1945 and 1959 a mass x-ray scheme was undertaken by the National Health Service to combat the then prevalent Tuberculosis. The x-ray revealed a shadow on Joe’s lung but it disappeared after he left EKRCC. The cause was given as continual exposure to diesel fumes.

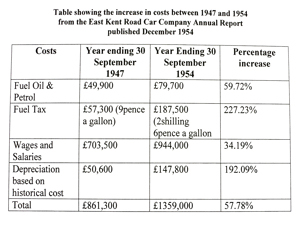

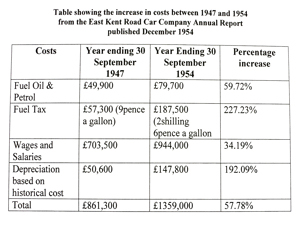

Table showing EKRCC costs 1947-1954. Annual Report December 1954

In October 1954, EKRCC put in another application to increase fares giving the justification as tax on fuel plus a nationally agreed wage rise. The proposed increase was ½pence and 1pence on single fares and 1pence and 2pence on return fares over certain distances, with an increase of up to 1shilling 7pence. The company presented a table comparing the rise in costs between September 1947 and September 1954. The total increase was 57.78% over that time. To support their claim, EKRCC argued that the tax was imposed on the company’s raw material, that of fuel, yet no other industry was subject to tax on their raw materials. Further, wages, which had continued to increase accounted for 40% of the total takings. Although, the company income was £82,224 net of tax other outgoings besides wages, other internal claims included running costs, overheads, leasing arrangements such as in Dover’s and vehicle maintenance and replacements. The South Eastern Licensing Authority listened but noted yet again that EKRCC had paid 8½% of net income in dividends and rejected the application on the grounds that the planned rise was ‘unnecessary at the present time.’

The foundation stone for Folkestone’s new bus station in Bouverie Square was laid 29 April 1954 by the town’s Mayor, Alderman John Moncrieff and came into operation in July 1955. The building of Canterbury bus station was delayed due to a dispute with the city council. It was finally resolved with an agreement whereby EKRCC exchanged its freehold holdings in St Peter’s Street and St Peter’s Place, adjoining Canterbury’s Westgate Towers, for freehold land between St George’s Lane and the City Wall, south-east Canterbury. The resulting bus station became operational in May 1956.

10 Pencester Road – EKRCC Booking & Enquiry Office where the Doctors surgery is today. Julie Wood’s Dad

In Dover, the EKRCC facilities consisted of a converted semi-detached house, number 10 Pencester Road, and a temporary repaired bombed out bus garage in Russell Street. Within the Pencester Road building was the booking, enquiry and parcel offices, administration offices and staff canteen and restroom. The parcel office was a legacy of the arrangement that EKRCC had made with Southern Railway in 1928. There were no off-road bus or long distance coach parking bays, instead the public accessed buses and coaches parked alongside the pavement on the southern side of Pencester Road. The 21-year lease over the provision of Dover bus services by EKRCC, which had been ratified in 1937, was coming to an end and the council, because of the situation in Pencester Road and the war damaged bus garage, were far from happy with EKRCC. They therefore were seeking an Act of Parliament to repeal their own powers under the 1936 Act which enabled the council to run their own company from 1957.

Both the 1936 Act and the Act that Dover Corporation were seeking covered a number of local issues but under the 1936 Act the Corporation acquired powers to operate their own bus service. This, however, did not come into effect until the expiry of the 21-year agreement the council had made with EKRCC and that would be on 31 March 1958. Under the agreement, EKRCC were obliged to pay Dover Corporation 75% of the net income earned by their services that operated within the town’s boundaries. The 1936 Act as it stood, meant that the Corporation would be obliged to take over the running of the town’s bus services with all the expense this would entail. If the Act was repealed, then the council could negotiate a new agreement with EKRCC and the Bus Company would continue to provide the town’s bus services.

James A Johnson Dover’s Town Clerk 1944-1968 who led the town’s negotiation team for the 1958 new bus contract.

Batting for Dover in the negotiations was the bullish town clerk, James A Johnson, who had a reputation for getting his own way. At the end of December 1955, as negotiations were about to start in the New Year, Johnson announced that it was expected that EKRCC ‘would make substantial monetary payments to the Corporation for many years to come’. He went on to say that EKRCC would ‘provide a new bus garage in Russell Street and a bus station in the town centre’. The bus station, according to Johnson, was to be similar to those in Canterbury and Folkestone. What actually happened at the negotiations is unclear as the details appear not to have been recorded. What is known is that EKRCC emphasised their financial woes and the final settlement for Dover, was so poor that it caused acute embarrassment to both Johnson and the Corporation.

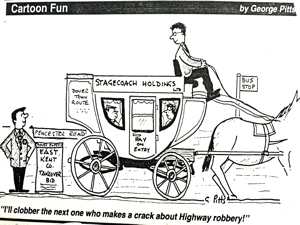

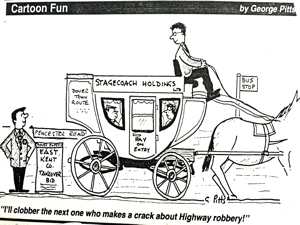

Following another increase in fuel tax plus a national 10shilling a week basic pay rise for drivers with corresponding rises for other workers within the bus industry, in April 1955, EKRCC applied again for permission to increase bus fares. Those using the buses during that era, may remember a cartoon depicting a bus with a large weight above illustrating the heavy burden of fuel duty. EKRCC also wanted to abolish workmen’s special concessionary fares from 1 May that year. KCC mounted a campaign of opposition against both and were vociferously supported by 22 local authorities, including Dover. The proposed increase in the price of a single fare was up to 50% and it was expected to raise £120,000 in revenue for the company that year. Permission was given but EKRCC did better than they expected, as there was a railway strike in June that increased the number of bus passengers. Albeit, a further bus drivers pay rise was sought and this went to the Arbitration Tribunal. In November 1955 the Tribunal awarded a pay increase of 11shillings a week with corresponding rises for support staff.

East Kent Road Car 1956 AEC Reliance with 41-seat dual -purpose Weymann body in Pencester Road awaiting departure to St Margaret’s. Vic Underhill

Jointly, the 2 pay rises cost the company £145,000 per annum and when 10 new one-man operated buses arrived in 1955, they were seen as a way of cutting operational costs. They were part of a batch of 41-seater buses made by Associated Equipment Company (AEC) whose chassis works were in Acton west London. With the generic name of Reliance, they all had Weyman bodies and were front-entrance single-deckers. This was the first time that EKRCC had used this company and the engines were positioned under-floor increasing the amount of passenger space available. Subsequent deliveries had this feature. EKRCC said that the ten with cabs adapted for one-man operation was part of a pilot scheme for busier routes and a number were based in the Dover and Deal areas on routes 76, 78, 80, 89 and 93 but the staff were far from convinced. Nonetheless, it was recognised that the smaller 20-seater one-man Dennis Falcon buses were proving inadequate to meet demand even on their more rural routes, such as the 92 to Capel and 93A to West Langdon.

Within a year of the previous bus fare increase, EKRCC applied for a further increase to raise another £60,000. The South Eastern Licensing Authority sanctioned this in April 1956 much to the anger of KCC, Local Authorities and the public in general. In Dover angry letters were written to the local paper and an Appeal was sort by 15 Kent Local Authorities. At the tribunal the opposition to the fare increase stated that EKRCC had paid out share dividends of 25% the previous year but were forced to accept that the ordinary share dividend pay out, although far greater than was practical, was actually 8½% and the Appeal was lost.

A further 22 Weymann bodied AEC Reliance 41-seater coaches were delivered in 1956, and in the following two years the last Guy Arab IV double-deckers to be ordered by EKRCC arrived. This final batch of 25 had a more stylish body and seated 61 passengers. On arrival the corresponding number of old vehicles were withdrawn and from 1956 the 20-seater one-man Dennis Falcon buses were up-seated to 25 and later 29. In late 1955, EKRCC provided vehicles linking up with Skyways Coach-Air flights from Lympne to Beauvais, France. They then went on to link up with Silver City from Lympne to Beauvais. Some of the Dennis UF coaches with central entrance Duple bodies were rebranded and used for this service along with AEC Reliance coaches.

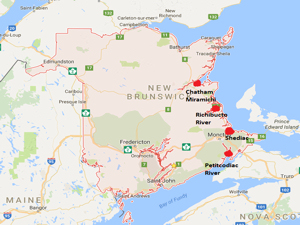

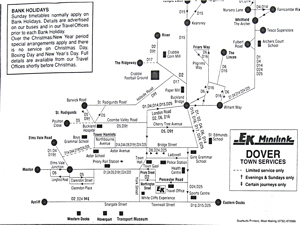

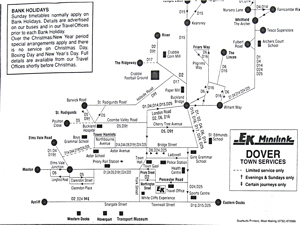

Map showing the course of the River Dour through Dover’s town centre in the north is Pencester Road where EKRCC had their offices and most of the bus termini. To the south, on St James Street/Russell Street, was the Bus garage. Service Publications 1990

While Dover Corporation’s Bill to Parliament was still under consideration, discussions with EKRCC ensued. These included Dover’s planned bus station and bus garage along with the leasing arrangements with EKRCC as public transport providers within the town. The contract for the latter was due for renewal in March 1958. During the negotiations, Dover Corporation agreed to give up their powers to operate public transport services and in return, EKRCC agreed to build a bus garage in Russell Street and a bus station in Pencester Road. EKRCC also agreed to only use one-man operated bus services in the town at peak times. However, in August that year EKRCC introduced all day one-man operated buses on certain routes in the Dover area as an economy measure. Passengers were expected pay the exact fare into machines called ‘robot conductors‘ and no change was given!

At the request of the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, Dover Corporation were asked to submit a plan for the devastated area of Woolcomber Street, St. James Street and the many smaller intersecting roads and streets. This was submitted and although the proposed bus station in Pencester Road was north of the area under consideration, the council included it. Their submission also included a special war memorial garden around the war damaged bus garage in Russell Street. EKRCC strongly objected, saying that they had plans to build a new station in Pencester Road and a new bus garage on the Russell Street site starting in 1957. Further, they said, the bus garage would include a memorial plaque to those employees of EKRCC who had been killed on 23 March 1942 by the bomb dropped from a German Junkers JU88. Dover’s Bill received Royal Assent and negotiations over the Dover Bus lease were started.

The weather in February 1956 was abnormally cold with blizzards and ice. This made driving difficult and impossible on some 48 of EKRCC bus routes and it was recorded that some 140 vehicles were abandoned. In October 1956, President Gamal Addel Nasser (1918-1970) of Egypt nationalised the Suez Canal, which threatened the UK’s economic and military interests in the region. On 5 November joint UK and French forces defeated the Egyptians but the Canal had been blocked to all shipping. The impact included a rise in fuel prices and the reintroduction of fuel rationing. The latter meant a cut of 10% in EKRCC supplies and this led to a reduction in services. Under the Hydrocarbon Oil Duties (Temporary Increase) Act 1956, fuel tax was increased by a further 1shilling a gallon and EKRCC received permission to temporary increase all fares by the same proportion. Both the fuel rationing and temporary tax increase finished in March 1957 and, at the same time, the temporary bus fare increases were withdrawn.

EKRCC bus garage in St James Street in this photograph is taken from Russell Street looking west. The back of Holiday Inn on Townwall Street and facing the sea, is on the left. Burlington House ahead showing the arch over St James Street that led out to the one way King Street. Buses on leaving the garage would turn left on to St James Street and then right onto the one way Russell Street. On arrival they would leave Townwall Street turn into Mill Lane and then left again into St James Street as can be seen by the coach in the photograph. On leaving the bus garage they would turn left onto St James Street and then onto the one way Russell Street that would take them to Townwall Street. At that time they could turn right into St James Street and go through Market square, and up Biggin Street. However, but to the one way system, if the bus was going any where else, from King Street it would have to turn right on to the then ancient and narrow Dolphin Lane – at the back of the bus garage – from where they could reach the one way Russell Street. They would again turn right until they reached the two way Townwall Street. c1975. The photograph has been provided by Dover Museum

On receipt of a War Damaged claim EKRCC started work on building Dover’s new bus garage on the former bus depot site in Russell Street. This was designed to house 90 buses so the new garage was considerably larger taking up part of what had been Leney’s Phoenix Brewery and with the entrance opening up onto St James Street. In the late 1960s a complex one-way system was introduced in Dover and all the buses left the garage by way of King Street, with those going through town going via Market Square. For the remainder particularly the route became much more complex as described in the caption to the photograph from Dover Museum. The new building included underground storage tanks capable of holding 30,000 gallons of diesel fuel. The working relationship between EKRCC, Belgium Marine and Europabus promised an increase in the number and extent of Continental tours in the summer of 1957. With the success of the two batches of AEC saloons, the Company ordered more AEC single decks and 12 luxury coaches. As the company had expanded its South Coast Express service they had ordered a further 39 single-decker dual purpose coaches, which arrived in 1957. These were all bodied by Beadle, the Kent builder but they were the last such bodies received by EKRCC.

In Dover that year, the Happy Travellers band, made up of EKRCC off-duty Dover bus drivers and conductors were successfully entertaining locals. However, on 20 July 1957 bus drivers in the provinces belonging to the T&GWU went on strike. This was in support of a pay rise of an extra £1 a week in an effort to bring them more into line with their London counterparts. The latter were paid 30shillings 6pence more a week. Windscreen stickers were made available by motoring organisations such as the Automobile Association and the Royal Automobile Club for car owners who were prepared to offer lifts to people waiting at bus stops. The government supported this by saying that they would cover any payouts in cases of accident where the insurance was inadequate.

In 1958/9 the highbridge Guy Arabs double-deckers were up-seated to 58 by the addition of two extra seats upstairs providing much needed further capacity. On 3 November 1957 the EKRCC application to increase fares was granted. In the application to the South Eastern Licensing Authority, EKRCC argued that it was to go some way to contributing to the cost of new double-deckers. These, they said, would have entrances at the front so that drivers could see that passengers were safely on board. In his speech to the shareholders that year Chairman Beddow, looked at the fall in net income for the year, which was £76,768, being down by 22% on the previous year. This, he blamed on the strike, which had occurred in the prime revenue season. Beddow also blamed the costs of running morning and afternoon school services as they made an average loss of 61%. As the company was obliged to provide the school services, loss making rural bus services were reduced. Apologetically, Beddow told shareholders, the amount they received in dividends would be less than the previous year but the ordinary dividend payments remained at 8½%.

East Kent Road Car Company World War II Memorial (detail) to those killed on the evening of 23 March 1942 by an enemy bomb dropped on the bus garage on Russell Street. Dover Transport Museum.

EKRCC new bus garage in Dover officially opened in September 1958 and was later rebuilt to face the back of the Holiday Inn, in St James Street. Much larger than the old premises, it had the capacity for 90 vehicles with workshops, offices, stores and staff facilities. The promised memorial plaque was also erected – now in the Dover Transport Museum. However, the promised bus station was no longer on the agenda. This, said EKRCC chairman Beddow, was due to a change in policy within the company. EKRCC had found that although the new bus stations in Canterbury and Folkestone were popular with both passengers and the councils, they made little difference to the number of passengers using the buses. This, he said, was due to the fall in the price of cars, the availability of hire purchase and the fast new motorways that were being built. People were turning away from public transport in general and television was keeping people at home in the evenings. Dover Corporation and the local press expressed their anger, particularly about buses parking at the bus stops in Pencester Road, which was the major source of congestion in the area.

The first of 40 front-entrance, AEC Regent V double-deckers, bodied by Park Royal of West London, with seating for 72 passengers and with front entrance doors controlled by the driver were delivered. Slightly longer than previous double-deckers they had a completely new layout inside, with staircase and passenger door at the front which, according to Chairman Beddow enabled the driver to see that passengers were safely on board. Although publicity material said that the doors were extra-wide in a broad entrance. In fact the entrance was steeper than the previous Guy’s buses, which had a flat platform before an internal step. However, the new bus did have stanchions and handrails in the centre and at both sides of the platform to help with boarding. The 9.6-litre vertical AV590 forward-mounted engine gave a 125 brake horsepower and the 4-speed synchromesh gearbox enabled the driver to change gear faster. Unlike previous EKRCC buses, which had vacuum or hydraulic brakes, these new buses had pressurised air operated brakes. Costing just over £230,000, the first ones were assigned to Thanet replacing 40 x 1950 Guy Arab IIIs. These were then distributed to other depots across the company, including Dover, which received FFN 360-FFN 366.

EKRCC Wartime utility open-top Guy double-decker converted in 1960 to an open-top and introduced in Thanet in 1959. It was introduced to Dover for the south coastal route in 1968. Dover Museum

In the summer of 1959 EKRCC introduced its first open-top bus service by converting some of the wartime ‘Utility’ buses made by Guy Motors. Painted in the reverse cream and red livery, they operated out of the Thanet Garage. In 1968 one was introduced on an experimental service between Dover and Folkestone which was later extended to Hythe thence St Mary’s Bay and Lympne Airport during the following three summers. As a cost saving measure, by the end of 1959 EKRCC had over 100 of its coaches adapted for one-man operation including 26 former rear-entrance Dennis Lancet buses converted to front-entrance for this purpose. On 16 May 1960 Dover Harbour Board opened the Lighthouse restaurant/café at the end of the Prince of Wales Pier and for that summer EKRCC ran a bus service along the Pier!

East Kent Road Car Company 1960 AEC Reliance with 41 seat Park Royal body on the first day of the Dover-Deal-Margate run 26 May 1974. left, driver Richard Wallace, right inspector Bill Ratcliffe. R Wallace Collection

Lobbying from bus companies, amongst others, moved the government to implement ‘Clearway’s on certain roads. This permitted vehicles to stop only as long as necessary to pick up or set down passengers during certain times and thus it enabled traffic to flow more freely but at other times allowed for overnight and daytime parking when the road is not so busy. In Dover, the council talked of introducing clearways along Pencester Road during peak times, to stop buses parking there! EKRCC took little notice as they were more interested in lobbying to increase the size of coaches for their Continental services. Following the recommendation of the International Convention on Road Traffic at Geneva in September 1949, Continental coaches had been allowed to be 36-feet in length and 8feet 2½inches in width, while British coaches were limited to 30-feet in length and 8feet in width. This difference, meant that Continental companies could carry a maximum 45 passengers against 41 on British coaches. EKRCC eventually won and in 1962 the company ordered 20 x 36feet long AEC Reliances with 46 seats. The coaches had Park Royal bodies, 9.5litre engines and over the next four years the Company had added a further 58 to their fleet.

EKRCC moved its headquarters out of the temporary offices at Odsal House, Harbledown, to a new state-of-the-art building in Station Road West, Canterbury in 1960. More single-deck dual-purpose coaches arrived, all bodied by Park Royal and delivered in two batches, 40 in 1960 and a further 19 in 1960/61. Increasingly, all but trunk routes were converted to one-man operation. The company also ordered more AEC Regents that arrived in the years 1960-62 in two batches. These had a more angular design and those based in Dover, all half-cabs, came from the second batch. However, the most notable delivery, as far as Dover was concerned, were three lowheight, 13feet 6inches, double-deck AEC Bridgemasters to operate the 129 route to the St. Radigunds estate, which could not accommodate the standard highbridge double-decks. This was due to the low, 14feet 6inches high, railway bridge over the then Union Road (from 1964 Coombe Valley Road). Formerly, the route had been served by ageing, lowbridge Leyland and Guy buses.

Ernest Marples (1907-1978) was the Minister of Transport from 1959-1964 and was also a director of Marples Ridgeway civil engineering company. Founded in 1948 by Marples and engineer Reginald Ridgway, the company’s projects included road construction such as the A329(M), M56 and M27. In 1962 Marples was responsible for the Transport Act which dissolved the British Transport Commission and established the British Railways Board. In anticipation of this, Marples appointed Dr Richard Beeching (1913-1985) who infamously ravaged British Railways. The result was major closures of lines and stations and these were offset by government funded motorway construction! This major change in transport policy was not lost on EKRCC, who ordered 78 x 36foot single-deck coaches, the last one arriving in 1966. Of interest, the later ones had forced-air ventilation and panoramic windows. In 1964, EKRCC introduced AEC Reliance coaches with Duple Commander bodies that were mainly used for Continental tours. These coaches replaced 1957 Beadle-bodied touring vehicles that were re-deployed for British long distance tours.

Pencester Road, the demolition of properties in October 1964 to make way for the shopping mall along the north side of the road. Kent Messenger

Although Dover still did not have a bus station, because of the collection of bus stops along the south side of Pencester Road plus offices in the nearby building, the area was referred to as Dover bus station. This was the case at the beginning of 1964 when St Martin’s Property Company of London announced plans to build a £100,000 new shopping centre opposite Dover’s bus station. Development began later that year on the three-storey block of twelve shops and a supermarket with the demolition of properties facing Pencester Gardens. However, the false impression that Dover did have a bus station led to local uproar. By the end of that year EKRCC, who owned the former bombsite on the south side of Pencester Road between number 7 and the River Dour, submitted plans to Dover Corporation. This was for a booking and enquiry office on the site, which were completed the following year. At the same time, mention was made of the possibility of demolishing existing properties on either side of the Maison Dieu Road end of Pencester Road and redeveloping the sites to create a bus station.

By this time the development of Buckland housing estate had begun in earnest. To meet the health needs of folk living on the estate and elsewhere in Dover a group of ten local GPs inaugurated a plan under the 1964 National Health Act, to establish a health centre. Under the Act, Local Authorities, such as KCC, were given the power to provide, equip and maintain such health centres where family doctors may work closely with the local authority health services. KCC agreed as the site chosen on Maison Dieu Road, would enable the greatest access of patients as close as possible to the proposed new bus station. Further, some of these General Practitioners occupied 3 Pencester Road, owned by KCC along with the adjacent properties. The Dover Health Centre on Maison Dieu Road, as it was/is called, was the first in Kent, cost £120,000 and opened in 1967.

EKRCC income had fallen from £149,501 for 1961 to £146,562 for 1962, even though fare increases had been successfully achieved. In 1961 a trial bus service was introduced between East Cliff and Connaught Park via Castle Hill, returning by Frith Road and Maison Dieu Road. The annual payment to Dover Corporation for 1961-62, was £3,200 and a pay rise costing EKRCC £77,000 was agreed. This, it was planned, was to be partially offset with a productivity deal, which was expected to net £50,000. The productivity deal failed to realise the expected return, nonetheless, dividends on shares remained at 8½%. In March 1962, due to the lack of bus parking facilities in Dover, a bus driver parked a single decker workmans’ bus in a car park in Townwall Street one evening. This was normal procedure when another driver was to take a workmans’ bus out in the early hours of the next morning. When the early morning driver turned up, the bus was not there. It was later found abandoned and badly damaged in Reach Road, St Margaret’s. In the hope of stopping such action again, EKRCC talked of expanding the size of the garage in Dover and also to include lock-up facilities in the proposed new Pencester Road bus station.

East Kent Road Car Company AEC Regent V with Park Royal body delivered in 1964. On London Road, Buckland. Eric Baldock

Private car ownership was escalating and was taking its toll on the number of bus passengers. At the same time management and employees relations were turning sour and this went into a nosedive in spring 1963. EKRCC not only discouraged bus crews to remain members of the T&GWU; they actively discouraged new employees joining the union. Matters came to a head on 1 June 1963, when some 3,500 busmen working for the EKRCC and the Maidstone and District Motor Service, went on strike to allow all employees to join the T&GWU. They won, bus fares increased and further strike action took place for pay increases which were given with Union endorsed productivity deals. Yet, EKRCC net income actually increased in 1964, such that the dividends paid to shareholders was 10%!

In 1966, EKRCC instigated a policy, without Union agreement, to stop payments to bus crews for work over and above their contracts. This was done by rewriting job descriptions to incorporate extra duties into established contracts. A walkout ensued in June 1966 but this had little effect on company income. At Folkestone’s Grand Hotel, EKRCC invited 200 guests to celebrate its silver jubilee on 4 October that year. Heading the guest list was Alfred Baynton. Others included representatives of the 22 local authorities in whose area EKRCC operated. The invitations had been sent to and accepted by senior and retired employees and representatives of the T&GWU. In his speech, EKRCC Chairman Beddow said that the company employed over 2,000 of which 442 had completed 25years service or more, 117 had 40-years service or more and the longest serving employee was lathe operator Reginald Taylor of Canterbury. He had completed 50years with the company for which he was presented with a gas cooker. The Chairman also told his audience that EKRCC had 622 vehicles, 2,160 employees, ran 137 different services, covered 17,625,000 miles in the previous year and carried 60million passengers.

EKRCC Bedford 1967 VAS with Marshall 29 seat body. Service 135 then 309 to the Citadel, Western Heights. Richard Wallace.

The success of the 36feet AEC vehicles led to the purchase of 4 Marshall of Cambridge bodied buses in 1965 on the same AEC chassis. Used as crew-operated buses at first, they, and a subsequent batch of 10 arriving in 1967, were to usher in one-man operation on a number of trunk routes from 1967 onwards. However, reluctance by staff to operate them on a one-man basis to their maximum 51-seat capacity saw most of the second batch temporarily reduced to 45-seats. In 1966, vehicles with 53 seats were allowed to be one-man operational. Before that year one-man operated buses had to be 45-seaters or less. In 1968 a batch 25 x 53-seaters arrived, some of which were reduced in seating capacity. Albeit, following an agreement with the Unions, they were allowed to operate at their full capacity from late 1968. This enabled most of the EKRCC’s longer routes, such as between Dover and Folkestone and Dover and Canterbury, to become one-man operational. In 1967, 10 small Bedford VAS buses with 29-seat Marshall bodies were delivered and these allowed the replacement of the Dennis Falcons which worked on Dover’s Capel, West Langdon and the Citadel, Western Heights routes.

East Kent Road Car Company AEC Regent V double-deck 1966 bus now owned by the Home Front Tours outside the Dover Transport Museum. Norman Burnett.

From 1961 more Regent buses began to arrive, these had more angular half-cab Park Royal bodies but otherwise the chassis were similar to earlier AEC Regents, making up a fleet of 161 such vehicles. By this time EKRCC’s sister company Maidstone and District were purchasing rear-engine vehicles, such as Atlanteans and later, Daimler Fleetlines, for all new double-decks but EKRCC preferred to stick with the conventional chassis of the AEC Regents for double-decks and Reliance for single-decks. Modern observers tend to believe that this was possibly due to the influence of EKRCC’s Chief Engineer of the time Mr. S.H. Loxton. In 1966 and 1968 two rear-engined AEC Swift coaches were also trialled but Reliance’s were still ordered for single-decker coaches up to and including 1968. A further 36foot 8inch AEC Reliance service single-deckers came into the fleet in 1968 but these had Willowbrook bodies, a change from the large numbers of Park Royal service coaches that had been purchased since 1962.

Even though EKRCC fares continued to increase and for the years 1965 to 1967 they continued to pay out 10% of net income in share dividends, the actual income of the company continued to fall. EKRCC was not the only bus company facing falling demand and the Labour Party’s Minister of Transport (1965-1968), Barbara Castle (1910-2002), proposed to effectively nationalise the country’s local bus companies. The government had set up the Transport Holding Company using the previously nationalised former Tilling Group of bus companies and in November 1967 British Electric Traction Company sold its Public Service Vehicle interests to the Government for £47m. At the EKRCC shareholders meeting in February 1968, the Chairman, Raymond Beddow, announce his retirement.

He told shareholders that, ‘Some years have been good and some not so good but all in all the company has given a good and faithful service to the public and I am confident it will continue to do so.’ His successor as chairman was J H Richardson and at about the same time the Transport Holding Company announced that it would be acquiring the minority shares of the various companies that had come under the umbrella of British Electric Traction Company. For EKRCC minority shares, their holders were paid 44shillings 6pence per share and EKRCC was transferred to the Transport Holding Company.

Jim Skyrme. Chairman of the East Kent Road Car Company who took the company into the National Bus Company in 1967. 30.12.1971

As part of the nationalisation, the Transport Holding Company acquired a 75% shareholdings in chassis builders Bristol Commercial Vehicles and body manufacturers Eastern Coach Works based in Lowestoft, Suffolk. Leyland Motor Corporation owned the other 25% in the two companies and of note, in 1968 Leyland Motor Corporation merged with British Motor Holdings to form the British Leyland Motor Corporation. In July 1967, Richardson resigned from EKRCC and S J B (known as Jim) Skyrme, the Chief Engineer with the British Electric Traction Company, was elected Chairman.

The following month it was announced that Norman Todd, a full time member of the Central Electricity Generating Board, on retirement was to be the part-time Chairman of the new National Bus Company and T W H Gailey, the full-time Chief Executive. Norman Todd, as part time chairman of NBC received £5,000 a year, at a time when the average wage for a man was £1500 a year. Gailey, who was also the chairman of the Tilling Association Ltd, received between £7,500-£9,000 a year for his NBC job. There were also four part time members of NBC’s Board, three of which were, Alderman W Alker – Bury Transport Committee, A P DeBoer and Sir William Hart (1903-1977) – Clerk to the Greater London Council and each were paid £1,000 a year. The fourth member was the full-time chairman of the Scottish Transport Group W H Little who declined the offer of a salary.

Nationalisation – East Kent Bus Company

East Kent Bus Company 1969 Daimler Fleetline with Park Royal 72-seat Highbridge body in EKBC poppy red and sporting the NBC logo. Now owned by Phil Drake and Dave Ferguson. Mark Bowerback.

The National Bus Company came into operation on 1 January 1969 and was obliged to show that it had broke-even at the end of every financial year. They had, under their control approximately 20,000 public buses and coaches – nearly one-third of all those operating in the UK – and control of assets worth over £100m. NBC did not actually run bus services but were the owner of a number of regional subsidiary bus operating companies that were locally managed with their own fleet names and liveries. East Kent Road Car Company was renamed East Kent Bus Company (EKBC) and its livery was poppy red and cream with East Kent in white followed by the double-N (National Bus Company) arrow logo. In the name of economy there was rationalisation that led to amalgamations, as later happened with EKBC and M&D, the west Kent bus company. The main financial role of NBC was that of channelling government grants into the individual companies and negotiating subsidies from local authorities, such as KCC.

In 1969, the government made a grant of 50% of the cost for one-man operated double-deckers and EKBC ordered 20 Daimler Fleetline double-deckers. After trials as driver/conductor operated buses they were all finally based at Thanet. They were aimed at one-man operation and at that time Thanet was the only depot that was agreeable with regards to double-deck operation. At the same time 10 AEC Swift rear-engine coaches arrived with Marshall of Cambridge bodies followed by a further 15 similar vehicles in 1970/71.

Strike – Picket Line Notice. Dover Transport Museum

The General Election was held on 18 June 1970 bringing the Conservatives into power. Not long after EKRCC crews belonging to the T&GWU, like their 64,000 municipal transport employees and 98,000 private bus company employees elsewhere, entered into a dispute with the NBC over pay. In essence they wanted a 25% pay increase. Negotiations broke down and an overtime ban together with a work to rule with regards to one-man bus crews ensued. The dispute reached this level in July but then collective bargaining started to break down. In some parts of the country agreements were reached, with an average £2 a week wage rise accepted. In the EKBC area, the dispute had started just before the schools broke up and with less demand on its buses, the management coped. When the men finally returned to work in the autumn, they found a lot of the rostered overtime had gone thus reducing their take home pay. At Folkestone the men published their own satirical magazine on the dispute – On the Buses – and were supported by local socialist groups.

NBC’s revenue in 1969 was £148.7m giving a final profit of £800,000. In 1970 it was £163.7m but the final accounts showed a loss of £8.1m. The number of passengers carried had fallen by 10%, while wage and price inflation had taken their toll exacerbated by the industrial unrest. In March 1970 new drivers hours regulations, which restricted the number of hours drivers were allowed behind the wheel meant that more had to be employed. The most serious problem, it was said, was that of loss making routes. Local Authorities were obliged under the 1969 Act, to subsidise unprofitable but socially valuable services with the Ministry of Transport paying half the cost. This was not policed and therefore many Local Authorities either ignored the directive or only half-heartedly made an effort. In consequence, except for the most serious loss making services, NBC complained that they had to provide the services. In order to help NBC’s finances for 1971, the government gave a grant of £6m.

East Kent Bus Company 1971 AEC Swift 51-seater with Alexander body, 301 Athol Terrace – Maxton service. Dover Museum

In 1971, with the arrival of a further 12 AEC Swifts, with Alexander W bodywork and painted in traditional EKRCC livery they were the last new buses to feature these colours. Most of these buses were based in Dover where the conductors were made redundant as the new buses replaced the double-deckers in the town. The final conversion of Dover’s last crew-operated routes to one-man operation took place in September. The Dover and Folkestone depots were refurbished to deal with one-man operated buses and Deal depot, for the same reason, was given a make-over the following year. However, the Faversham depot was closed.

Due to a combination of an order for double-decks diverted by NBC away from East Kent and the difficulties with expanding double-deck one-man operation due to staff resistance EKBC acquired 30 Leyland Leopard coaches from Southdown Motor Services. These were refurbished and most were repainted from green and cream to traditional EKRCC livery, leaving a few to enter service with traditional Southdown livery. They were based at Folkestone until they were all withdrawn by 1977. In 1970/71 a number of Plaxton-bodied coaches arrived and were far more comfortable and stylish than their predecessors. 20 were 36foot x 49 seat cars and 10 had 40foot chassis and 53 seats.

In 1972, the first of a fleet of new 49-seater single deck Leyland National coaches started to arrive. All with the NBC poppy red livery, the first batch comprised 26 vehicles, the order being completed in 1973. The funding for the Leyland National buses was partly paid for by a government grant and they were a natural outcome of the assets acquired during Nationalisation. Most notably the 75% holdings in Bristol Commercial Vehicles and Eastern Coach Works of which British Leyland Motor Corporation owned the other 25%. Park Royal, in 1949 had become part of Associated Commercial Vehicles and in 1972 Leyland Motor Corporation acquired the latter. In 1968 Leyland Motor Corporation had merged with British Motor Holdings (BMH) to form British Leyland Motor Corporation. This was, at that time, the fifth biggest company in the UK and one of the top three motor manufacturing companies outside of the United States.

Under BMH, previously known as British Motor Corporation were numerous well known motor companies including Austin, Morris, Riley, Wolesley, MG, and Jaguar and through the latter, Guy motors which was once popular with EKRCC. Leyland’s stable included Triumph, Rover, Alvis and its large commercial range that included those mentioned above. The deal between Leyland and BMH was a one-for-one share exchange and the value of BMH at the time was £193million and for Leyland, £217million. British Leyland Motor Corporation was nationalised in 1975 following which many of its subsidiaries closed, including Park Royal, Bristol Commercial Vehicles and Eastern Coach Works.

Fred Wood (1926-2003), a successful businessmen, was appointed chairman of NBC in 1972 and in April, an EKBC holiday coach was the first vehicle over the new viaduct when it opened from Limekiln Street to Marine Station and Admiralty Pier. Not long after, the former EKRCC now EKBC holiday and regular long-distance coach services, became part of the South East region of the newly created National Travel Fleet. Wood instigated the white livery with the NBC logo and the word NATIONAL, in alternative red and blue lettering painted on the side. National Travel Fleet was rebranded as the National Express in 1974.

East Kent Bus Company 40-seater AEC Reliance 691 with Duple Bodywork on the Scotland Tour 1970. Dover Museum

The former pride of EKRCC and main source of super-profit before Nationalisation was the holiday service and this lucrative operation was maintained by EKBC. There was a major upgrade in 1970 when 8 luxurious AEC Reliance 691 touring coaches with Duple Commander IV bodywork arrived. However, in 1971 Jim Skyrme, the former Chairman of EKRCC who took the firm into Nationalisation, succeeded Gailey as Chief Executive of the National Bus Company at the end of 1971, a position he held for five years. In 1972, under Wood’s directive, EKBC’s holiday enterprises were taken over and together with other pre-nationalisation bus company holiday coach services were rebranded as National Coach Holidays. The company was then run from Cheltenham but re-privatised in 1986 when it was sold to Shearings Group. They, amongst other types of holidays, specialised in coach holidays. Wood was knighted in 1977 for his reorganisation of NBC.

As part of the restructuring in the name of efficiency, the Maidstone and District Bus Company was amalgamated with EKBC. This loss of individual identity had a negative effect on staff moral that was exacerbated by another NBC policy. Senior and middle managers, keen on promotion, were moved around the various former companies within the NBC stable thus undermining identity cohesiveness within the companies. NBC also had a corporate painting policy, for both the inside and outside of buildings. When the outside of the bus office in Pencester Road was painted NBC Corporate Blue, there was a local outcry as it was out of character with the area. This, senior management within NBC chose to ignore. In the spring of 1973, EKBC had all its bus services renumbered. Dover and Deal services were given the prefix 5, Canterbury services were given the prefix 1, Thanet 2, Ashford 3 and Folkestone 4.

Dover Harbour Board reception terminal at Eastern Docks 1953. Lambert Weston for DHB

EKBC, in 1974, introduced a regular coach service between London and Paris and London and Brussels via Hoverlloyd Hovercraft Company at Pegwell Bay near Ramsgate. Following rebranding, that year, the Dover – London coach service was given the registration number 007 after James Bond. In the accompanying National Express publicity it was said that Ian Fleming, the author of the James Bond books, had moved into a beach cottage in St Margaret’s Bay following the War, which was correct. However, National Express publicity went on to say that Fleming had taken the number, 007, from the Dover to London coach number of that the time – which was a figment of NBC’s publicity department’s imagination! Nonetheless, the coach service from the Eastern Docks to London proved so popular that by the end of the decade there were 14 departures a day and National Express opened a waiting room and enquiry office within the Docks reception terminal.

Throughout the 1970s the momentum of the public abandoning bus travel in favour of private motor vehicles gained pace. In order to achieve its financial target, EKBC continued to replace crewed with one-man operated buses and then started cutting routes, particularly those in rural areas. One of NBC main roles was to negotiate subsidies from local authorities, such as KCC however, they seemed somewhat lax in this area. To make this an obligation it was incorporated into the Local Government Act of 1972, which also obliged local authorities such as KCC to develop and co-ordinate efficient transport systems for rural areas. Further, as a result of the 1972 Act, on 1 April 1974, Dover District Council was formed and shortly after proposed a scheme of concession bus fares for a limited number of people living in the District. That year, EKBC advertised for new staff, promising recruits free bus travel.

East Kent Bus Company number 87 Dover-Ramsgate service 51seater AEC Swift 69 with Alexander body 1971. Dover Museum

One new recruit was retired Major General Derek Carroll (1919-1996) O.B.E. Chief Engineer, British Army of the Rhine 1970-1973. The Major General lived in Shepherdswell and on taking up the post of bus driver with EKBC, he told reporters that he believed in starting at the bottom. A year later the Major General and EKBC parted amicably with the retired Major General proudly announcing that he had gained the Heavy Goods Vehicle and Public Service Vehicle licences. After working as an Immigration Officer at Ramsgate Hoverport in 1976 the Major General set up his own coach business and also worked part-time as Kent Ambulance driver for the next ten years!

During this period, the NBC, which owned some 700 sites, many in the centre of towns and cities, changed its policy of selling off sites that were surplus to requirement. The Chairman, Fred Wood, successfully argued, particularly against government mandarins, for a planned programme to assess such sites potential for redevelopment. He told parliament that together, the sites had a book value of £36m but with a current market value of between £50m and £60m. This could be increased, he said, if NBC, using outside experts, prepared schemes, sought planning permission and sold the development rights but retained the freehold. His advisers assessed that this policy could potentially net NBC £200m-£300m if all sites were dealt with this way. From the resulting revenue, Wood said, new attractive bus stations, with restaurants, car parks and pedestrian ways could be built. Following this statement, hopes were raised that Dover would get one such bus station in the town in the area of Pencester Road.

Bristol Commercial Vehicles VRT double-deck vehicles, in the mid-1970s, entered the fleet. The first batch having highbridge14feet 6inches Eastern Coach Works bodywork. Later batches had rarer Willowbrook highbridge bodies before the final batch delivered in 1980/1 had lowheight,13foot 8inches Eastern Coach Works body. These replaced the last of the AEC Regents from normal passenger services in the early 1980s. Although painted in the standard NBC/EKBC poppy red, increasingly EKBC were being criticised as poppy red faded into dappled pink generally making the buses look old and uncared for.

In June 1976 one of EKBC coaches carrying children and their teachers, collected from London, was being taken back to the Royal School for Deaf Children in Margate. Near Sittingbourne, the coach hit a stationary lorry on the M2. One child, age 12years, and an adult, who had been assisting the lorry driver, were killed in the subsequent multi-vehicle pile up. Fifteen children and three adults were hurt. Doctors and nurses, at the hospitals where the children were taken, had difficulty on communicating with them until the police brought in members of the congregation from a church service for the deaf to help. This was the worst road accident in which an EKBC vehicle was involved.

Dover Precinct south from Biggin Street looking down Cannon Street to the Market Square. LS 2016

The York Street bypass in Dover, opened in 1972 to traffic between Folkestone Road and Snargate Street. With the removal of through traffic from the town centre, DDC, in 1979, gave approval for a pedestrian precinct and implicit were plans for EKBC to create a bus station somewhere close by. The area designated for the precinct was from the Market Square to Pencester Road. EKBC objected saying that it would financially hit the company hard, such that town services would have to be reduced. KCC, took the objection up on behalf of EKBC and threatened to take DDC to court, not only because of the precinct but also for not allowing EKBC to park over-night in the Russell Street car park. DDC conceded on both issues but when the new precinct opened on 27 February 1981, there was general criticism that it was half-baked because buses, along with service vehicles and permit cars, were allowed to drive through it. Further, the notion of a bus station failed to materialise yet in 1979 new joint EKBC and Maidstone and District headquarters were built in North Road, Canterbury. The former headquarters in Station Road West were sold and sometime after turned into apartments.

In 1979 DDC announced that as the owners of 2,4,6 and part of 8, Pencester Road, next to the EKBC office at number 10, they planned to demolish the buildings and applied to KCC for outline planning permission. This was to erect offices for their Technical Services Department. As DDC was made up of three and a half former councils – Dover, Deal, the Rural district and part of Sandwich, they had inherited small offices throughout the area. Eventually, the Technical Service office project on Pencester Road was abandoned with the building of the large Council complex at Whitfield. Albeit, within their application to KCC for the Pencester Road project, DDC mentioned a proposed Magistrates Court, on the site on Pencester Road next to the EKBC and National Express bus park.

Daimler Fleetline Park Royal by former Betteshanger Colliery offices now owned by Phil Drake & Dave Ferguson August 2010. Phil Drake

Nationally, NBC told their various subsidiaries, including EKBC, to assess how they were meeting local needs and a market research programme was launched. Called the Viable Network Project and subsequently referred to as the Market Analysis Project (MAP). Each bus company was obliged to consider its existing, short and long term demand and potential for bus routes, fares, frequency and lengths of journeys. Also alternative forms of transport, school runs and the necessity of providing non-profit making services such as to villages and isolated areas. It involved employing numerous part time workers, including this writer, requiring the completion of pre-prepared questionnaires by interviewing passengers at bus stations, or as in the case of Dover bus stops in Pencester Road, as well as house to house calls. Needless to say, along Pencester Road, where this author was stationed, the views of bus users was dominated by the need of a bus station with somewhere warm and dry to sit and clear details of which bus stop to use, where to catch it and easy to read time tables.