In 1938 Robert Letheridge Murray Lawes was the owner of the 423 acres Old Park estate on the north east side of Dover (see part I of the Old Park story). This was originally two separate estates, the originally Old Park Mansion estate boundary went along the full length of Whitfield Hill on the south side from Whitfield to the then London Road. Along London Road to the then Green Lane, where there was a small farm, the track up the hill going east until what is now Melbourne Avenue, but at the time another track, was reached and along that track northwards to the top of Whitfield Hill. Old Park mansion was within the boundary of this part of the estate. The remaining 198 acres juxtaposed the south of the Mansion estate excepting that the boundary was several hundred yards short of the London Road.

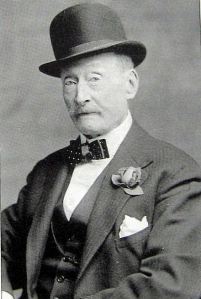

Murray Lawes, as he was known, was a major advocate in the National and Kent Playing Fields Associations, having been a founder member of both. However, with war looming, on 24 November 1938 he gifted with covenants Old Park Mansion estate to the Ministry of War. By the outbreak of World War II (1939-1945), Lawes had joined the army rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. In the summer of 1939 Old Park Barracks were built and the Royal Artillery (RA) moved in. Various RA and other units stayed at Old Park for rest, recuperation and in some cases, hospital care between combat assignments in the different theatres of war.

During that time there were many heroic acts by various members of the different units, however, one is particularly remembered in Dover. In spring 1942 Lieutenant John Warren, an officer in the Royal East Kent Regiment – the Buffs – was stationed at Old Park. On the evening of 23 March he and some of his colleagues went to the Granada cinema in Castle Street, Dover, but while watching the film Junker 88s bombers circled the town and then began dive-bombing. One of the bombs hit the Conservative Carlton Club in the nearby Market Square killing 57-year-old Cllr. William Austin a sign writer of Pencester Road: haulage contractor Percy Snelgrove age 60 of Millais Road; Co-op bakery manager Donald Mackenzie age 53 of Barton Road and William Bank age 53 of Avenue Road. In the Square, Private Alan Bowles age 20 was killed by falling masonry, while inside the devastated building a woman and two children were missing.

The Granada cinema was evacuated and as the young Lieutenant and his colleagues were running through the Square they heard about the missing woman and children. They went to investigate and were told that the two children, Pauline (15) and Ivan (4) Cleak were found sheltering under a billiard table but their mother, Lilian Cleak was trapped and buried under the heavy debris. Lt. Warren, a short wiry rugby wing and three-quarter realised that he was small enough to wiggle through a tiny gap. This he did with his feet held by fellow subaltern, Robert Brownrigg and helped by Captain Arthur Harvey of the Salvation Army, a tunnel was dug to prevent Mrs Cleak from being crushed to death. His colleagues from Old Park, some of whom had only recently joined up from local reform schools, were also involved in the rescue by shoring up the debris including the use of a car-jack.

When Lt. Warren reached Mrs Cleak he lay her on her side, cleaned her face and gave her an injection of morphia while Dover’s Medical Officer of Health, Dr E Hughes, shouted the instructions as to how it was to be administered. Lt. Warren then instructed the rest of the team how best to free Mrs Cleak, an operation that took five hours. In all Mrs Cleake was buried for thirteen hours. Following the rescue Lt. Warren and his colleagues returned to the barracks at Old Park.

The next morning, not having had any sleep, Lt. Warren was late on parade and was put on a charge. His colleagues in the rescue were also in trouble for being late and they too were punished but not one said anything of the events the night before. On the Friday that week, the Dover Express published an account of the rescue, such that Lt. Warren was able to make a full report naming all the individual combatants involved and subsequently all the charges were dropped. For their bravery, Lieutenant John Warren was awarded the George Medal and the Salvation Army Captain Arthur Harvey the British Empire Medal.

During the continuing attacks on Dover at this time it is difficult to ascertain how Old Park faired as damage to military establishments were not made public. However in September 1944, when the Allied troops were closing in on the German troops still occupying the French coastal towns of Boulogne, Calais and Dunkirk. Dover was under fierce attack. Indeed, the town, already having earned the reputation of ‘Hell Fire Corner,’ suffered the heaviest shelling bombardment from the French coast including Old Park. On Tuesday 26 September, the last of thirteen days of continual bombardment, two soldiers were killed at the Barracks.

Immediately following the ending of hostilities, in 1945, ships came into Dover packed with soldiers returning from the Continent. Old Park, along with Connaught Barracks, Duke of York’s School and the former Oil Mills were turned into transit camps. It was estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 soldiers were dealt with daily in the town. Long convoys of army transport carrying men to and from Old Park was a regular occurrence.

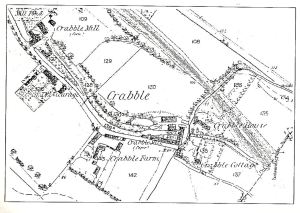

The damage Dover had sustained during World War II was proportionally greater than in any other town in the country, or so it is said. 957 houses had been destroyed; 898 seriously damaged but in part fit for uneasy habitation; and 6,705 were less seriously damaged. Public, general businesses and industrial premises were also badly damaged. Dover Corporation’s Town Clerk, James A Johnson, spoke to Lieutenant Colonel Lawes about utilising what had been the playing field adjacent to Chaucer Crescent to erect prefabricated ‘temporary’ homes. Lawes had gifted, with covenants, the land to the town as a playing field but for war purposes it had been put under cultivation due to food shortages. At the time it was still under cultivation but was eventually expected to revert to a playing ground. Lawes was concerned that if the land was used for temporary housing, temporary may become permanent. However, he did suggest another site to the south of the then Green Lane.

This was declined, instead, so it appears, the council or Town Clerk, asked for the site of Green Lane farm, approximately between where Winant Way and Roosevelt Road are today. Again Lawes declined saying that the area was not suitable for housing, as it was prone to intermittent flooding caused by underground springs. Again he offered the site across Green Lane but it would seem that some sort of altercation took place between the Lieutenant Colonel and James A Johnson. This ended with Johnson seeking and gaining, in 1946, a compulsory purchase order for the whole of Lawes remaining 198 acre Old Park estate! Lawes moved to West Kent, where he continued his fight on behalf of the Kent Playing Fields Association for playing fields.

Initially, 480 prefabricated ‘temporary’ homes were built on both sides of Green Lane. These took three days to erect but as some came from the U.S. and included fridges, due to a shortage of electricity the appliances could not be used! Initially the development was named Green Lane estate as the council objected to any reference to Lawes or Old Park. The roads were named after Commonwealth cities and towns that had sent food parcels to the town during and after the War. However, again, out of animosity to Lawes, there were to be no playing fields.

In 1949 the council decided to build the first 50 houses of a new estate at Green Lane but shortage of materials meant that the prefabs had to stay longer than originally envisaged. It was not until 1965 that the development of the Green Lane estate began in earnest and eventually it became Dover’s largest housing estate. Except for the pre-war playing field at the end of Chaucer Road and the playing fields that were part of the two schools, no playing fields were laid. The areas that Lawes had warned were prone to flooding due to underground springs, proved to be correct. The last of the prefabricated bungalows were demolished in 1971.

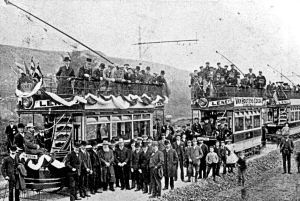

Following the War, the 21st Training Regiment occupied Old Park Barracks until April 1947, when following a re-designation they became the 121st Training Regiment. They left Old Park on 30 January 1948 and were replaced in March by the 14th Field Regiment, who had been abroad for 22 years. The 1st Royal Sussex Regiment arrived at Old Park in July that year pending an amalgamation of the 1st and 2nd Battalions and were followed by the Depot Battalion R.A.S.C. The Depot Battalion stayed until September 1950 when they were replaced by the Somerset Light Infantry then quickly followed by 1st Battalion of the Buffs. This was the first time in forty years that the Buffs had been stationed in the town so an official greeting was laid on when they arrived in December that year from Sudan.

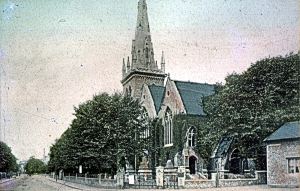

To provide for the soldiers spiritual needs a chapel was built and in April 1949 was dedicated by the Bishop of Dover to St Alban the Martyr. However, it did not have a church bell. In Dover most of the churches had suffered war damaged and were repaired, that is with the exception of both the old and new St James’ churches. Old St James’ Church became the ‘Tidy Ruin’ that can still be seen today. It had been expected that the noble new St James’ Church would be repaired but despite mass protests in Dover, in 1952 a Commissionary Court ordered the Church to be demolished.

The Court also ordered that the altar was to be broken up and burnt ‘under supervision’ and the font, pulpit and anything else that could be removed, was to ‘be pounded to dust.’ During the demolition the church bells were left exposed but one was so corroded that it had to be thrown away. The other bell, however, was ‘rescued’ one night and given sanctuary in a rapidly built tower close at Old Park Barracks! The site of St James’ (New) Church is now St Mary’s School playing field, Maison Dieu Road.

The Buffs left Old Park in November 1951 to go to Enniskillen, Northern Ireland. It was not until December 1952 that the Barracks were in use again, when the 72nd L.A.A. Regiment arrived. They moved on after six months for Hong Kong but in October the Buffs returned with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers. At the time Kenya, east Africa, was a British colony and the indigenous Kikuyu wanted independence. There had been a series of uprisings and revolts and in 1953, there was the Mau Mau rebellion. The units at Old Park, which by this time included the Headquarters of the 19th Infantry Brigade, left Old Park for Kenya. Dover townsfolk lined the streets to wave them off and to wish them a safe journey and a speedy return. The uprising lasted until 1959 and the country gained its independence in 1963.

In June 1956 the Royal West Kent’s arrived in Dover from Germany and moved into Old Park Barracks. They had hardly unpacked when on 26 July, the President of Egypt, Gamal Abdel Nasser, announced the nationalisation of the Suez Canal and along with the rest of the Dover Garrison, the Royal West Kent’s were redeployed. Then on 23 October, in Budapest, Hungary, students organised a demonstration against Soviet Union control of the country. Although the students were hoping for a good turnout they did not expect the thousands that came and marched with them. This was the start of the Hungarian Uprising that was to last until 10 November, when the Soviet Army moved in and regained control. This led to a massive exodus of refugees fleeing Hungary.

On 19 November 1956 the Ostend boat arrived at Dover carrying 236 refugees and more arrived over the next few days. Initially, they were met by relief workers and dispersed throughout the country. By the end of the month, it was decided that Dover’s temporarily empty army barracks would be used to house up to 3,000 of the refugees. By early December, Old Park Barracks had 900, Connaught and Northfall Barracks, 1,300 each and as the month progressed, more were accommodated. Troops, still in the UK, together with a considerable number of Dover folk tended to the refugees needs until the British Red Cross, with Hungarian help, took over the administration and the refugees were dispersed.

Junior Leaders

At the time a relatively new army squadron was looking for a new, larger home. They were the Junior Leaders of the Royal Engineers. It was in 1946 that the Army Council had been authorised by Government to maintain the Army Cadet force, ‘as an efficient organisation that blended military and social activities of the established corps at the same time as meeting youth training in the wider sense.’ The Council felt that the opportunity should not be lost of utilising commissioned, warrant and non-commissioned officers who had active experience during the war, as teachers. The subsequent discussions led to the formation of the Junior Leaders – young men straight from school, who would be trained to provide the regular army with a supply of manpower that was trained in leadership skills in order to take on the mantle of the senior Non Commissioned Officer (N.C.O).

The first 50 recruits arrived at Chatham in 1950 and a further 30 at Aldershot at the same time. The courses proved to be such a success that aggressive recruiting followed. Anthony Head (1906-1983) was the Secretary of State for War (1951-1956). His theme, in 1955, when he presented the Army estimates for that year, was Army restructuring. He stated that there would be a greater emphasis on Brigades being self-contained groups, easily detachable but re-attachable to the Division. This change included addressing the major problem that most of the recruits to the Armed services came via National Service. Peace time conscription, or National Service, started on 1 January 1949 when all healthy males age 17 to 21 years old were expected to serve in the Armed Forces for 18 months, and remain on the reserve list for four years after. However, said the Minister, it was not until their final six months that they were most economically viable as tradesmen and/or non-commissioned officers. Conscription ended in 1960 with the last conscripted soldiers leaving the service in 1963. The way forward, he said, was the expansion of the Junior Leaders.

At the start of 1955 there were 580 Junior Leaders and ‘A’ and ‘B’ Squadron Royal Engineers (RE) was formed. By the end of that year there were, in total, 4,700 Junior Leaders. It was estimated that by 1959 there would be 6,000. Lieutenant Colonel Murray Lawes, hearing of this, suggested Old Park Barracks as ideal, especially as the philosophy behind the Junior Leaders was close to his own and complied with the covenants of his 1939 gift of Old Park to the Ministry of War. The Ministry agreed and Old Park Barracks at Dover was selected as the Headquarters of the Royal Engineers Junior Leaders.

The first intake of Junior Leaders into the refurbished barracks took place in December 1958 under the first Commanding officer (C.O.), Lt Col R.L. France R.E. In January 1959 ‘C’ Squadron was formed by combining ‘A’ and ‘B’ and the Junior Leaders Squadron RE became known as ‘The Junior Leaders Regiment Royal Engineers.’ Dover was their Regimental home. The objective was to teach the boys general and higher education, sport, discipline, teamwork and military skills to a high standard with the overall emphasis on developing qualities of leadership.

After 2 years at Old Park, the Junior Leaders Regiment threw open their doors to invited civic dignitaries, employment exchange representatives and the press to show what the training scheme had to offer. This event took place in January 1961, at which time there were 500 boys at, what was termed, the Army boarding school. They told their invited guests that their stay at Old Park was for two and a half years during which they learnt a trade. All of the recruits had signed on for at least six years and the guests were surprised to learn that the high standards required were such that a large proportion of applicants was rejected. The visitors came away impressed.

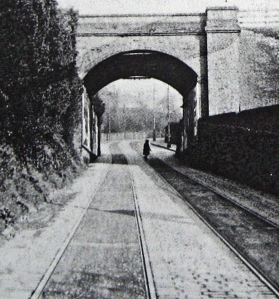

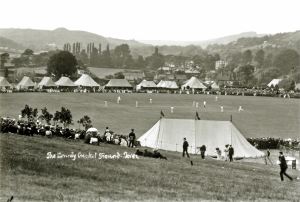

From their first arrival at Dover, the Regiment had made every endeavour to assimilate into the town. In 1959, for the first time, the council’s Entertainments Committee arranged a Whit-Monday (last Monday in May) attraction. The occasion included the ‘Beating Retreat’ by the Junior Leaders Regiment from Old Park. So impressive were they that over the next few years, they were seen at numerous military tattoos and almost every public occasion held at Crabble Athletic Ground.

In 1957 the Junior Leaders Regimental Band had formed and for many years after, performed at Chelsea Football Club matches. In 1969 they combined with the Corps of Engineers Band for the final of the Football League Cup at Wembley. On these occasions they wore the scarlet full dress uniform that included busbies identical to those worn by the Corps of Engineers on ceremonial occasions before 1914.

To meet the requirements of the Junior Leaders Royal Regiment R.E. which was to amalgamate with the R.E.M.E Junior Leaders Regiment, in 1961, the government spent £250,000 enlarging and converting Old Park. In March that year, Junior Corporal Malcolm J Thomas won an Amateur Boxing Association championship and was subsequently selected for England to fight an East Germany team. Then in August, 50 Junior Leaders passed off to the men’s service. General Sir Frank Ernest Wallace Simpson (1899–1986), the new Chief Engineer took the salute and inspection.

The following year, 1962, having gained permission from Lieutenant Colonel Murray Lawes, 120 married families’ houses were built at the Barracks adding to the housing stock. At about the same time, the bell from the then recently demolished Garrison Church on Western Heights was moved to Old Park and put into store until an envisaged new church was built. The ornate Gothic cross was also taken from the old Garrison Church and given a new home in the then Chapel at Old Park.

Boleh, built in Singapore and sailed to Salcombe in the UK 1950 under Commander Robin Kilroy. Thanks to Roger Gray

The Boleh – meaning ‘Can Do’ in Malay – a Chinese junk built in Singapore and sailed to the Salcombe UK in 1950 under Commander Robin Kilroy, was loaned to the Junior Leaders Regiment in 1963 for three years, by his nephew Lieut. George Middleton. Used for adventure training the Boleh carried over 300 young Sappers (the nickname for members of the Royal Engineers) a total of 6,500 miles. The regular trips were to Calais and Boulogne, but she was also taken to Guernsey and Middleburg in Holland.

As part of an extensive modernisation scheme of the camp, the ancient Old Park mansion house, restored and partially rebuilt in 1876, was demolished to make way for the new Garrison Church. The foundation stone for the Church was laid in December 1966. That year the Junior Leaders raised £500 for soldiers blinded on duty in Northern Ireland and they also raised money for charity by undertaking a marathon ride from John o’Groats to Old Park. Other good deeds included the building of a sun shelter for the then Cornfields retirement home, at Whitfield. For all of these and other projects the Junior Leaders were presented with a mascot, Rover a pup of Petra, BBC Children’s Television programme dog.

The internationally famous pop group, the Beatles, were awarded the M.B.E. in the Queen’s the Birthday Honours list of June 1965. Retired Royal Artillery Officer, Colonel Frederick Wagg M.B.E, returned his award to the Queen as a protest and although the Colonel actually lived in Old Park Avenue, when the national press got hold of the story they wrongly assumed that the Colonel lived at Old Park Barracks. The barracks were quickly under siege by the national media. Much to the amusement of the young sappers, four look/sound-a-likes donned themselves in ‘Beatles’ style wigs and played the fab four well! Apparently, it was not until one of the officers called the young sappers bluff did the media realised that they had been fooled! Nonetheless, the Colonel’s protest was taken very seriously but a straw poll showed that two-to-one people in the country were in favour of the Beatles receiving the award.

Presentation of Rover, the pup of Blue Peter’s Petra. Note the Junior Leaders Regimental Band wearing the full dress uniform incluing busbies identical to those worn by the Corps of Engineers on ceremonial occasions before 1914. Kent Messenger December 1965

The 1969 Pass on Parade was a great occasion for Dover as it was taken by the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1966-1978), Sir Robert Gordon Menzies (1894- 1978) on one of his visits to England from Australia. At the time the Regiment’s compliment was 700 and for a Junior Leader to Pass On, he had to pass the Army Certificate of Education – Intermediate test. The Education Department was run by a Major in the Royal Army Education Corps and there was a staff of 20 professional teachers, both military and civilian. The Army Certificate of Education – Intermediate test qualified the Junior Leader educationally, for promotion to Sergeant.

Once achieved, the Junior Leader had the chance of passing the Senior Test, which qualified him for promotion to Warrant Officer and to take ordinary level certificate of education (‘O’ levels). At the time only children who attended public, grammar and certain technical schools were given the possibility to take ‘O’ levels. As Junior Leaders offered an excellent chance to climb the academic ladder, the training enabled many of them to become commissioned officers. The academic subjects taught were English language and literature, mathematics, map reading, current affairs, engineering and building drawing, applied physics, military administration, art and woodwork. The flexibility in the curriculum meant that it could be tailored to meet the individual’s needs and non-academic activities.

The halcyon days of the 1960s were coming to an end, and in 1972 the country was heading towards an economic recession. Cut backs were imposed and, among other government activities, there was talk of severely reducing or even axing the Junior Leaders. At the time it was a Conservative Government and Dover’s Member of Parliament was Conservative, Peter Rees. In the House of Commons, against what was expected of him, he put a strong case for both keeping the Regiment and expanding the academic curriculum to include an ‘O’ level year that non military school children attending local secondary modern schools could also join! Although this never reached fruition, by the end of the year reassurance came that the Regiment would remain intact and at Old Park Barracks.

World War II hero Major-General Sir Gerald Duke (1910-1992), who had attended Dover College as a boy, opened a museum of military engineering at Old Park in August 1979. Three months later, in November, General (later Field Marshall) Sir Ronald Gibbs (1921-2004) toured Old Park Barracks and presented long service and good conduct medals. He then went to dine with the Dover Garrison Commander, Colonel Maurice Atherton, later Brigadier and now President of the Dover Society who, at the time, resided at the Castle. At the Castle towards the end of that month, the Junior Leaders erected a Trebuchet medieval sling shot machine.

The Junior Leaders Band together with the 3rd Queen’s Band played on the Seafront, in 1980, during the Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother’s birthday celebrations. The Queen Mother was the Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1979-2002) and as such made a point of being in Dover for the celebration. In September the following year, Captain James Winter of Dover and member of the Zaire River Expedition, took a party of 32 Junior Leaders to Tunisia for three weeks. There the young men helped archaeologists in a dig at the ancient Punis port at Carthage, replaced broken headstones in British war cemeteries, were taught desert navigation, how to deal with scorpions and snakes as well as visiting desert forts.

However, in Dover, things were not going well for Junior Leaders as gangs of local youths took up the ‘sport’ of ‘squaddy bashing.’ On one occasion a gang of 25 youths armed with studded belts, bottles, sticks, motor bike helmets and cricket stumps attacked four Junior Leaders. Eleven of the group were arrested and sentenced by Dover magistrates’ court. That summer the Regiment held an open day in an attempt to improve relations with the town.

February 1984 saw Les Welham, the Junior Leaders fencing coach become the Champion at Arms after winning the three-weapons competition by coming first in the sabre, second in epee and third in foil. He had previously won the title in 1981. The Junior Leaders, as well participating in local sports fixtures continued to play a constructive role in Dover. Under the auspices of English Heritage, they helped to clear the Drop Redoubt on Western Heights of dumped vehicles, machines and general rubbish and in 1987, they were involved in repairing the Drop Redoubt. The following year they were at the Castle moving the ancient Queen Elizabeth pocket pistol indoors.

In August 1984, the Ministry of Defence announced that after examining ways of streamlining the Army’s training and organisation the Junior Leaders’ Regiment, Royal Engineers would be leaving Old Park in 1988/89. The regiment was to amalgamate with the Apprentices College at Chepstow. At the time there were 600 Junior Leaders at Old Park, plus 40 officers, 100 permanent military staff and 100 civilians. The following year Lord David Trefgarne, the Parliamentary under Secretary of State for Defence announced that following a review it was decided that the move would not take place until 1990. Further, that Old Park would be redeployed for other military uses.

Tragedy struck on 1 August 1989 when three Junior Leaders were killed when their Lynx helicopter crashed at the Stanford Army training ground, near Thetford, Norfolk. They were Stuart Driscoll age 16 from Carnoustie, Tayside, Peter Lowe age 17 from Croydon and Christopher Lapping age 17 from Stourbridge, West Midlands. The pilot, Sergeant Peter Bennett of the Army Air Corps, was also killed. Five others survived. The accident was due to a mechanical fault.

The 1990 Options for Change Defence Review confirmed the removal of the Junior Leaders from Old Park and also the closure of the Barracks. The last Pass Off Parade was held on 26 October 1991 with the remaining 82 Junior Leaders were transferred to the Army Apprentice College in Chepstow to finish their training. The last Junior Leader to leave Old Park was Rob Doutch. During their stay in Dover, the Junior Leaders had made great contributions to the social, welfare and economic aspects of the town. Further, at Old Park, 240 locals were employed to provide support for the 600-700 Junior Leaders that would be stationed there at any one time.

The Junior Leaders were sadly missed.

Junior Leaders memorial plaque on the Cairn made by them and dedicated to all those who passed through Old Park Barracks. Thanks to Roger Gray

In 1992 the Junior Leaders Regiment Branch of the Royal Engineers Association erected a Cairn, built by ex-Junior Leaders, near what had been the Chapel. Dedicated to the thousands of boy soldiers who passed through the barracks and went on to serve their country in peace and war around the globe. Chief Royal Engineer, Lieutenant General Sir Scott Grant, unveiled the Cairn. In 2001, Major (Retird.) Dick Barton the Chairman of the Junior Leaders Regiment Association, with an original Junior Leader who came to Dover and Rob Doutch, the last Junior Leader to leave Old Park marked the 10th anniversary of the closure. Sadly, at the time of writing, the plaque and crest are missing from the Cairn.

Houses and Business Park

The Ministry of Defence put the 225 acre Old Park Barracks up for sale in 1991, with the caveat that the 91-acres of woodland was to be preserved as such. The houses on the site were still occupied by the Argyll and Sutherland Highland Regiment and were being considered for retention. Consultants, DTZ Debenham Thorpe drew up a planning brief for Dover District Council (DDC). At the time the estate included two adjacent and extensive playing fields with pavilions; an athletics track, two large parade grounds, a gymnasium, swimming pool, workshops, classrooms, indoor ranges, stables, garages, the chapel, offices and mess halls. The Dover Society put forward a strong case for the site to be converted into a Sports College.

The houses in 1992 were assigned to the ill-fated Independent Crown Housing Trust and subsequently became part of the package of Ministry of Defence housing stock that was sold en-masse to Annington Homes. They were still empty in 1996 when the decision was taken that the families of Ghurkhas, stationed in Hong Kong were to be returned to Nepal prior to the Transfer of Sovereignty on 1 July 1997. In the UK there was public outrage and in a letter to the Times newspaper, Chris Barnett, the Director of Health and Housing at Dover District Council, put the case for 120 Ghurkhas and their families to be housed in the still empty homes at Old Park. Annington Homes did not take up the idea and the houses remained empty.

DTZ Debenham Thorpe presented their Draft Planning Brief to DDC in 1995 by which time they had leased out buildings to a variety of small businesses. Their report ignored the Dover Society suggestion for a Sports College. Then, the Ministry of Defence, having found a potential buyer, said that the whole site was to close and all the incumbents were sent eviction notices. These were rescinded four days before the deadline and it then became known that Dover Harbour Board (DHB) was the potential buyer.

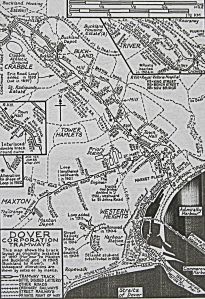

Entrance into the Old Park estate stating that it still is a Port Zone and Lorry Park. Alan Sencicle 2015

After long negotiations, during which time more businesses opened at Old Park, in March 1998, the site was formally bought by DHB. They announced, to a great fan-fare, that it was to become a Freight Village. Lorries, the people of Dover were assured, going to and from the Continent would be held at Old Park to ease the problem of congestion. The site would also be an operational base for all freight related activities to free up space at Eastern docks. To improve the road infrastructure from the A2 to the entrance of the proposed Freight Village, with DDC approval, DHB were given a £500,000 government grant. The road realignments were carried out and Dover’s Member of Parliament, Gwyn Prosser undertook the formal opening in June 2000. By this time the Freight Village had become a Port Zone – and according to the advertisement blurb of the time, would be used strictly for port-based industries as well as a lorry park. It was expected that 1,000 new jobs would created.

In 2003 DHB sold most of their holdings at Old Park, selling the remainder the following year. This was the former military houses together with a three-storey barrack block to the High Wield Housing Association. The Association refurbished their acquisition into 500 flats and Nick Raynsford opened the scheme. As a publicity stunt, the Minister of State for Housing and Planning abseiled down the former three-storey barrack block!

By 2005, DHB had sold off about two-thirds of the Old Park site that they had proclaimed would be a Port Zone and a variety of businesses, many non port related, had offices there. The former Junior Leaders sports fields, running track and officers’ mess had been sold for housing development. More of DHB’s acquisition has been sold since. Albeit, in 2009 a Public Notice was published by the Ministry of Defence, which served as a reminder that Old Park had been a Gift to the Nation and with Covenants by Lieutenant Colonel Robert Letherbridge Murray Lawes. The covenants almost certainly comply with the objectives that Lieutenant Colonel Murray Lawes spent his life fighting for (see Old Park part I), namely playing fields and restricted development.

The 91-acres of woodland that was to be preserved was finally put in the care of the Kent Wildlife Trust in 2011 by DHB.

The Dover Transport Museum has been given a home on the old Park estate and can be found in Willingdon Road on the Old Park estate and is well worth a visit. The Museum was founded in 1983 and occupying the old Water Works on Connaught Road, were facing eviction. The DHB Register later retitled Chief Executive (1983-2002), Jonathan Sloggett offered them a temporary new home in DHB’s former workshops on Cambridge Road. In the early 1990s the Transport Museum was on the move again as the Cambridge Road building was refurbished as the De Bradelei Wharf shopping complex that opened in 1993. Initially, DHB loaned them one of the former motor transport halls at Old Park until they moved to their present home (see below for details).

It was the members of the DHB Sports and Social club that suggested that the Buckland Mill Bowling Club be given a home within the precincts of the ruins of Old Park mansion. The Sports and Social club had moved into the former chapel in 1998, when their clubhouse adjacent Wellington Dock was scheduled for demolition. The Bowling Club had started in the mid-1920s but had been without a home since the closure of Buckland Mill in 2000. The Chief Executive of DHB, Bob Goldfield (2002-2013) opened the renamed Gateway Bowling Club green and pavilion on 3 August 2007. However, the DHB Sports and Social club was later closed and in 2013 the School for All Nations moved into the former chapel. This closed in Spring 2015.

Although a maritime college or university in Dover has been muted for a long time, in 2009 it was announced that the Dover Maritime Skills Studio was to open in September 2010. At the time the location had not been finalised but following the launch of the merger between West Kent College at Tonbridge and the then South Kent College that resulted in the ill-fated K-College in April 2010, the Dover branch was redecorated with a nautical feel. However, a couple of articles in local papers suggested that DHB were having talks with a view to open a Maritime University in September 2011 on the Old Park site. The following month articles in the local papers were saying that Dieter Jaenicke of Viking Recruitment was the innovator behind what eventually became the Maritime Skills Academy next to the Viking site at Beechwood on the Old Park estate. By 2012 courses were on offer and in November 2016 Princess Anne formerly opened the Skills Academy. The Academy provides training courses to help those working in the maritime industry deal with ominous situations on seagoing vessels.

The Legacy

Lieutenant Colonel Murray Lawes legacy to the nation was the upper part of his Old Park estate. What the demands of the covenants were, is neither in the public domain nor how long they lasted. The projects he particularly cared and fought for were playing fields and limiting development. It is known that the Junior Leaders utilising the Old Park estate fulfilled his wishes. Murray Lawes died in 1969, so what he might have thought of the subsequent use of his land after the Junior Leaders were moved out, one can only speculate.

What is known is that Murray Lawes would not have been happy that the post-War Buckland estate development that is on the lower part of what had been his land – there are no purpose laid municipal playing fields. The estate mainly consists of social housing and therefore has more than the average number of children, yet the only municipal playing field in the locality is the one he gifted to the town in the 1930s!

It is sad that the combination of a vindictive council and, what many call, an asset stripper have almost obliterated Murray Lawes memory in Dover. Albeit, there is one major legacy he left, that only time could destroy – and that is the memorable time had by the hundred-thousand Junior Leaders at Old Park Barracks!

Lieutenant Colonel John Letherbridge Murray Lawes – they and Dover are indebted to you!

- Presented: 14 November 2014

Junior Leaders Association:

Website: www.juniorleadersraoc.co.uk

e-mail: admin@rejuniorleaders.co.uk

Kent County Playing Fields Association:

Website: http://www.kentpfa.org.uk

e-mail: kcpfa@hotmail.co.uk

Dover Transport Museum:

Website: www.dovertransportmuseum.org.uk

e-mail: info@dovertransportmuseum.org.uk