Harbour of Refuge – A truly national work that would enable the rendezvous in times of war of the entire national fleet and serving as a national harbour of refuge, so much needed in the interests of humanity … Dover, holds the key of the Channel! (Steriker Finnis 1872)

UK Map showing the location of Dover and the English Channel

For centuries, it was through the English Channel that much of the commercial traffic in and out of the country passed. In the days of sailing ships, this depended entirely on the wind and weather and therefore a place was needed to shelter during storms. During his incumbency as mayor (1756-7), this was the basis of the argument presented by Captain John Bazeley, in a petition to Parliament for harbour improvements. He pointed out that Dover was the most favourable port of refuge between Portsmouth and Harwich and therefore was of national importance. His petition was effectively ignored.

In 1830, Henshaw Latham (1752-1846) was the Mayor of Dover for the third time. He was also a senior member of one of Dover’s two banking families, the Treasurer of Dover Harbour Commissioners, Warden of the Pilots’ Court of Lodemanage and Lloyds shipping agent. Latham was resolved to turn have Dover’s harbour expanded into a harbour of refuge stating, as Bazeley and many others before had, that sailing ships and the, then new, steamships, needed a haven in bad weather and somewhere to go for a refit even for the smallest problems. At that time, Britain had about 24,500 ships employing 250,000 men and for every sixteen sailors who died at sea, eleven died by drowning or in shipwrecks.

Dover Harbour Entrance by William Heath published 1836 by Rigden. Dover Harbour Board

The consensus within the shipping industry was that a place of refuge was needed between the Thames estuary and Portsmouth and the groundswell of national opinion was that it should be at Rye, Sussex. The argument rested on the depth of the channel leading to that port at a low water, which was estimated as 12-14 feet. Latham, however, was determined that if such a harbour was to be built then it should be in Dover Bay and his opportunity came in 1836 when the Dover Harbour Commissioners promoted a Parliamentary Bill. This was to raise £60,000 in an effort to combat the age-old problem of the Eastward Drift – causing the harbour entrance being blocked with shingle that, at times, rendered it useless.

The Parliamentary Committee sat between 12 May and 7 June 1836 and examined nineteen witnesses. The first to be called was solicitor John Shipdem, the Harbour Commissioners’ Register (now Chief Executive), who briefly outlined how harbour revenues were received. The second witness was Henshaw Latham and his evidence centred the need for a harbour of refuge. To back his argument, Latham provided evidence to show that 1,573 vessels had been stranded or wrecked off Dover between 1833-1835. That 129 vessels were missing or lost and in the case of 81 vessels, the entire crew had drowned.

One of the other witnesses was Daniel Peake, a Cinque Ports Pilot for 40 years, who was asked: ‘Have you had occasion to make use of Dover harbour as a harbour of refuge?‘

Answer: Yes.

Question: Coming which way?

A: From westward; sometimes from the eastward.

Q: Suppose you were taken in a heavy gale from the south-west, would you rather run for Dover or for Ramsgate?

A: At particular times, if there is no bar (caused by the Eastward Drift) before Dover harbour, I should run for Dover harbour.

Almost all the other witnesses concurred with Latham and Peake, they were Captain Edward Boxer – Royal Navy, William Cubitt (1785–1861) – Civil Engineer and Government Witness, Philip Going -Ship owner, Robert Hammond – Warden of the Pilots, Philip Hardwicke – solicitor and Receiver of Harbour Rents, John Hawkins – Clerk of Harbour Works, Humphrey Humphries – Chairman of the council Common Hall, John Iron – Harbour Master, Captain Harry David Jones – Royal Engineer and Government Witness, Isaac Pattison – Harbour Pilot, John Benjamin Post – Cinque Ports Pilot, William Prescott – Chairman of the Meeting of the Inhabitants, James Walker (1781-1862) – Harbour Engineer, Richard Wardle – Engineer’s Assistant and Lieutenant Benjamin Worthington – Royal Naval Officer and author of a plan to improve the harbour. The one witness who did not concur was Dover’s MP, John Minet Fector junior (1812-1868).

That year the South Eastern Railway Bill was going through Parliament and received Royal Assent on 21 June. If the problem with the harbour entrance could be solved, then folks in Dover generally assumed that the Railway Company’s main passage to France would be from their port. However, on Saturday 2 October, during a heavy gale, ships were forced to bear up to leeward in the Bay as the harbour entrance was blocked. Four seamen off the Dover ship Duncan were washed overboard and drowned. They were Robert and Thomas Ford, Thomas Dixon and Henry Bustard. Brigs off Sandgate, near Folkestone, and Ramsgate sank. Then, at the end of the month, the French announced that in future all mails would go to Ramsgate instead of Dover and the railway company started to look towards buying Folkestone harbour for their main crossing.

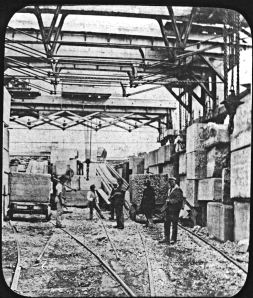

The Pent being scoured out to create the Wellington Dock. Dover Harbour Board

The Inquiry did galvanise the government into giving permission for work to be carried out on Dover’s harbour. The Tidal Basin was enlarged by about 5 acres, the Pent was scoured and lined and using the excavated mud both Northampton Quay and Street were created. The Pent was renamed Wellington Dock and was opened on 13 November 1846 by the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1829-1852) and chairman of Dover Harbour Commissioners.

In the General election of 1837, John Minet Fector junior was rejected in favour of Edward Royds Rice (1790-1878), who lived at Dane Court, Tilmanstone. He was a partner in the Latham Bank and his manifesto centred on a harbour refuge at Dover. Following his arrival at Westminster he pursued his objective with vigour and in 1839 he successfully laid a motion calling for an inquiry into the need for more harbours of refuge and a Commission was set up to look into the proposition.

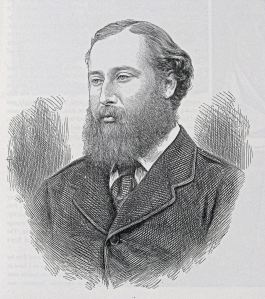

Edward Rice Liberal MP for Dover 1837-1857 who took on Parliament for a harbour of refuge at Dover. Dover Museum

Under Sir James Gordon the Commission included William Cubitt who had given evidence at the 1836 Inquiry and was, by this time, working for the South Eastern Railway Company (SER). The Commission concluded that there should be three large harbours of refuge along the south coast. For its part, SER had bought Folkestone harbour in March 1843 for £18,000 and were pressing for the proposal to be in Hythe Bay.

Although in opposition, the Liberal front bench and senior politicians enthusiastically supported the Folkestone proposition leaving only Rice, a back-bench member of the Liberal party, actively supporting Dover. With the full backing of the Duke of Wellington, over the next few years Rice pestered, cajoled and generally made himself a nuisance in the cause of Dover.

Eventually it was the Conservative Prime Minister (1841-1846), Sir Robert Peel (1788-1850), who took notice and Rice’s political party were outraged – a view shared by Liberal supporters in Dover who spoke of dropping Rice as their representative. Peel appointed yet another Commission, with the remit was to look at the loss of property and life in shipwrecks. The hearings were under Admiral Sir Thomas Byam Martin (1773-1854), a Conservative stalwart, and started on 1 May 1844. Martin was also a well-known naval administrator with a penchant for retaining well-stocked and highly trained dockyards capable of responding rapidly to any international emergency. His remit was to enquire:

i. Whether it was desirable to construct a Harbour of Refuge in the English Channel

ii. What situation would be best for such a Harbour?

Both Rice and Latham, the latter as a shipping agent and representative of the Pilots’ Court of Lodemanage, gave evidence. However, a strong argument was put forward from representatives from Rye that the harbour of refuge should be to the west of Dungeness, namely Rye. This was forcibly endorsed by one of the members of the committee, Sir William Symonds (1782-1856), Surveyor of the Navy. He argued that for military reasons in the event of war the naval harbour should be mid-point between the Downs and Spithead and on the windward side of the narrowest part of the Channel. This, he said, was Dungeness!

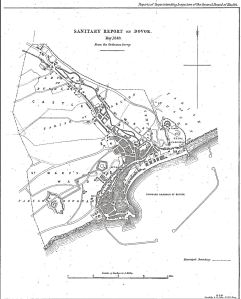

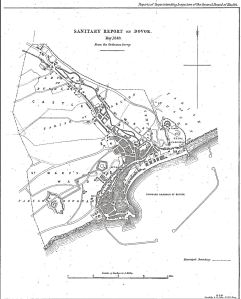

Harbour of Refuge proposal 1844 from Rawlinson Sanitary Map of 1846

On 7 August 1844, the Commission published its report and, except for Sir William, strongly recommended that Dover should be a combined harbour of refuge and naval base. Subsequently, William Cubitt, recommended that the harbour of refuge should be formed by a curved breakwater enclosing an area of 500 acres and would take over 15-years to construct. He estimated the cost at £1.5million. In France, the reaction was of horror as they perceived the proposal as a military threat and immediately instigated similar works along the French side of the Channel. However, in England, due to the unrelenting opposition from SER who had supported the Rye contingency, nothing happened. In Parliament, Rice kept banging the proverbial drum on behalf of Dover.

This led to another Inquiry, this time looking into why nothing had come of Martins’ inquiry! Its report was published on 13 November 1846, reiterating the earlier recommendations adding, ‘Dover, situated to a distance of only four miles and a half from the Goodwin Sands, and standing out favourably to protect the navigation of the narrow seas is naturally the situation for a squadron of ships of war. Its value in a military point of view is undoubted; but the construction of a harbour of refuge, there is, in our opinion, indispensable, to give Dover that efficiency as a naval station which is necessary to provide for the security of this part of the coast and the protection of trade.’ The report finished by saying that there should be an ‘Immediate commencement of the construction of a great National Harbour at Dover‘. In the meantime, on 10 April that year, Henshaw Latham died.

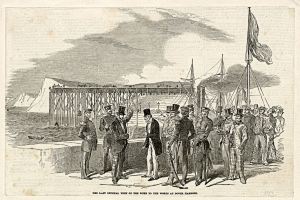

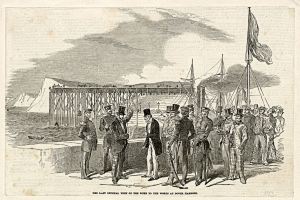

Admiralty Pier construction being inspected by the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) – Dover Museum

At last, in 1847, approval was given for four large harbours of refuge – Holyhead, Portland, Alderney and Dover. It was estimated that the works would cost in total £2,250,000. At Dover, the designed was by Sir John Hawkshaw (1811-1891), with the main building contractor Henry Lee & Sons. An 1848 Act of Parliament 1848 enable the Warden & Assistants of Dover Harbour to raise more money and work started in April 1848 on the construction of the west pier that became known as the Admiralty Pier. By early October 1850, the foundation of the pier was 650-feet long but on Tuesday 8 October an intense storm, centring on Dover destroyed all the works that had been undertaken.

Piles, 18-inches square were snapped and three huge diving bells were carried away to sea – two were later found. At daybreak, the bay was strewn with fragments of timber and machinery including broken cranes air-pumps and traversers. The Duke of Wellington rode from Walmer to inspect the damage accompanied by civil engineer James Walker – who had given favourable evidence at the 1836 Inquiry. Along with Colonel Blanchard of the Ordnance, Wellington went to the extreme end of what remained of the pier looking carefully at what had survived.

Work was restarted but by 1853, national discontent had been roused over the cost of building a harbour of refuge at Dover. In general it was believed that Folkestone – Hythe Bay would be the better place to site a harbour of refuge. Further, it was being said, that what remained of the proposed Admiralty Pier was putting the town of Dover in danger of being flooded. The critics added that this, ‘might be no bad thing as the population are made up of land sharks.’ Agitation was such that on 27 August that year Sir James Graham (1792-1861), First Lord of the Admiralty headed a retinue of delegates to Dover on an official fact finding visit. Captain Luke Smithett, of Dover, brought them to the town on the Vivid mail packet.

Admiralty Pier – Turret to right of lighthouse

The ship tied up on Admiralty Pier and the Mayor, Charles Lamb and the two members of Parliament, Edward Rice and Henry Cadogan – later Viscount Chelsea (1812-1873) MP for Dover (1852-1857) met the influential officials. The Board members inspected Archcliffe Fort where the Royal Artillery had recently fixed large guns to protect the envisaged harbour of refuge. At the time Napoleon III (1852-1870) of France, following an official visit to Calais and Boulogne, had suggested that one, if not both, ports should be expanded into harbours of refuge. The Board members report stated that work was progressing well and that the town and harbour was in danger but from forces in France. A subsequent Royal Commission recommended that the Admiralty Pier should be extended and that a gun turret should be incorporated.

At the time the Bill for the Canterbury-Dover railway line was going through Parliament that eventually became the London Chatham Dover Railway (LCDR). During the due process, they had added the port of Dover as the terminus and would take the line under the Western Heights. This, they argued, was to enable them to use the harbour of refuge as their main cross Channel port. SER had chosen to make Folkestone their main harbour for the Continent and had created a cross-Channel monopoly.

Admiralty Pier under construction. Dover Museum

The 1857 General election campaign in Dover again centred on the harbour of refuge. During the campaign, it was reported that between 1840-1855 the government had spent £278,000 at Dover. In 1856, a further £34,000 had been spent and that as expenditure on the other three harbours of refuge was also beginning to escalate that objections were being raised by the Board of Trade. In fact the Board of Trade had publicly stated that the need for harbour of refuge was not so imperative as before. This was because steam vessels were largely superseding sailing ships and thanks to parliamentary legislation and the supervision of the Board, ships were more seaworthy than formerly.

As the election approached, the landlubbers declined to support Edward Rice and he decided to retire and leave the battle to others. Albeit, Liberals Ralph Bernal Osborne (1808-1882) MP 1857–1859 and Lieutenant-General Sir William Russell, 2nd Baronet (1822-1892), MP 1857-1859, were selected and both had based their campaigns on the need for a harbour of refuge! Following the election Osborne was appointed Secretary to the Admiralty.

Admiralty Pier construction. Dover Museum

In 1858 a House of Commons Select Committee was set up to look into the supposed squandering of public money on the four ’great’ harbours of refuge. They found that approximately 1,000 lives and £1,500,000 of property were lost on average every year through shipwrecks on British coasts. Then went on to say that if the proposed harbours of refuge were completed and more were built, as long as the costs of these harbours did not exceed the financial amount lost through ship wrecks then they would be a worthwhile investment for the country at make. They recommended that £2million should be set aside for the building harbours of refuge. A Royal Commission the following year agreed and increased the recommended expenditure to £4million!

Aside from the harbour of refuge, as Secretary to the Admiralty, Osborne was instrumental in proposing the abolition of the Dover Harbour Commissioners. In the General election of 1859, he lost his sea but two years later, in 1861, the Harbours and Passing Tolls &c. Act came into force with the aim of facilitating the construction and improvement of Harbours by authorising loans to Harbour authorities.

Earl of Granville Lord Warden and Chairman of Dover Harbour Board c1890

This Act abolished Dover’s Passing Tolls and embodied within it a new constitution that led to the Harbour Act of the same year that abolished the Dover Harbour Commissioners replacing them with the Dover Harbour Board (DHB). As before, DHB was presided over by the Lord Warden (1866-1891) who, at the time, was George Leveson Gower the Earl Granville (1815-1891). However, the makeup of the Board was different and consisted of six members, two of which were members of Dover Corporation, two represented the railway companies, one the Admiralty and one the Board of Trade.

Dover Corporation’s representatives were appointed on an annual basis, one of which was the Mayor (1863 and 1864) – Captain Jeffrey Wheelock Noble RN. He was the superintendent of Pilots but on 21 March 1865, he died and the Deputy Mayor, Steriker Finnis (1817-1889) took his place. As Captain Noble had also represented the Admiralty on the Board, on 3 May, Finnis became the Admiralty’s representative and elected Deputy Chairman at the same meeting. He was to hold the position for almost a quarter of a century and throughout that time, the harbour of refuge was his main concern. The phrase, ‘Dover holds the key of the Channel’, was his.

Steriker Finnis

Nationally and in Parliament the costs of the harbours of refuge remained a source of discussion with some demanding for more such harbours to be built, others who wanted to see the big four completed first and a third group who saw the ventures a waste of money. By 1864, the total amount budgeted for the building of the big four was £5million of which £3,300,000 had been spent. At Dover the western pier – Admiralty Pier – was no where near completion and the design for the eastern arm had not even been approved.

The Board of Trade successfully argued that all works on the four harbours of refuge should stop once the £5million had been spent. In their argument they pointed out the ship owners, as a body, were unanimous in declining proposed aids to navigation if they have to pay for them. Secondly, they said, harbours such a Dover, where the newly built pier offers protection, the charges for marine insurance had not been reduced to vessels plying near the port.

Albeit, Finnis and the Board Register (now Chief Executive) – James Stilwell (1829-1898) – prepared a Bill for submission to Parliament. The proposal was for the deepening of the Bason, Wellington Dock and the Tidal Basin and for the technical details, the Board consulted Sir John Hawkshaw. He produced a scheme and estimated the cost at £166,000. During the preparation, an accident occurred that was to bring the Admiralty to openly support of Finnis and Stilwell.

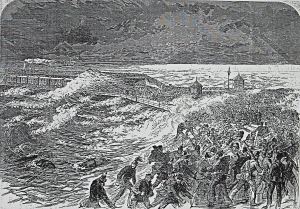

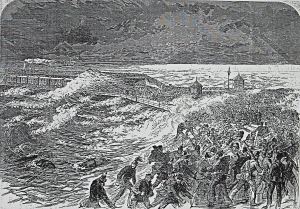

Ferret – Scene of the wreck. Illustrated London News 10.04.1869. Dover Library

The accident involved the sail training brig, Ferret on Easter weekend 1869. On board were 17 men, 8 stewards and 86 boys under training – some of which belonged to Dover Sea Scouts (now Sea Cadets). During a severe storm that weekend, the ship, which had been on a buoy, broke free and hit the Admiralty Pier. Eventually it sank but luckily all the crew and the boys were rescued. In the subsequent inquiry, the lack of the second pier of the proposed harbour of refuge was given as a reason for the mishap.

1871 saw the completion of the Admiralty Pier, 2,100-feet long and costing £693,077 but the harbour of refuge was put on hold by the government. On 24 July that year the Dover Harbour Improvement Bill received Royal Assent and work started on deepening Bason so that vessels drawing 21-feet could enter at high water. The Bason was completed on 6 July 1874, opened by the Earl Granville and was renamed Granville Dock.

With other works that the Board envisaged to be part of the harbour of refuge, the aggregate cost came to £74,416 13s 1d. Although considerably less than Hawkshaw’s estimation, as DHB income had been severely reduced following the abolition of Passing Tolls the money had to be raised by loans and the selling of property. The latter included part of the Matson estates that had been bequeathed to the Harbour Commissioners in 1721.

Following the Ferret Disaster and the Admiralty proclaiming the necessity for a harbour of refuge over next few years, ten schemes were put forward by DHB. The government however, was unrelenting and SER were backing councils in vicinity of Dungeness who were putting forward equally powerful arguments. One of the strongest arguments was to extend the SER line from Robertsbridge in Sussex to Dungeness where a harbour would be created by cutting through the point itself. The proposal again incorrectly stated that the French port of Audreselles (between Boulogne and Calais) opposite Dungeness was closer than Dover is to Calais. This time, it served to weaken the whole of their argument.

In August 1872, at a DHB Board meeting, presided over by Steriker Finnis, Dover representatives Samuel Metcalf Latham (1799-1886) and John Birmingham together with London, Chatham and Dover railway company’s representatives, James Staat Forbes (1823-1904), C W Eberall agreed to adopt a smaller scheme. This had been designed by Sir John Hawkshaw utilising the Admiralty Pier and enclosed 340 acres of sea space. This was to be ‘deepened so as to admit steamers of draught of not less than the Holyhead class.’ Other improvements were to include a covered walkway from both the LCDR Harbour Station and the SER Town Station. Each of the stations were to have a landing wharf, so that, ‘passengers could embark and disembark in comfort, whatever the condition of the weather.’

Dover Harbour late 19th century. Courtesy of Ian Cook

Afterwards, Finnis publicly stated that the representatives of the two railway companies had agreed to give sureties for the payment of interest on outlay etc. The estimated cost was around £200,000 and he finished by saying that it would be a ‘truly national work that would enable the rendezvous in times of war of the entire national fleet and serving as a national harbour of refuge, so much needed in the interests of humanity …

Dover, holds the key of the Channel!’

This was given both national and international coverage and it was agreed that Sir Andrew Clark would build the proposed harbour but a reassessment of cost increased the proposal to £970,000. In May 1873, it was reported by the former Packet Company owner, Joseph Churchward (1818-1890), in his Dover Chronicle that the Harbour of Refuge, as had been agreed, would go ahead. This was sanction by the 1873 Dover Harbour Act and in July the Admiralty ship, Porcupine, arrived in Dover to undertake survey for the planned harbour of refuge. At that time, the Liberals were in power and to ensure the government received value for money they added six government appointees to the Harbour Board, two of which came from the Board of Trade.

However, later that month, the Treasury, through the Board of Trade, proposed that both railway companies (SER and LDCR) should contribute £10,000 each and charge a 6d (2½p) per passenger toll towards the scheme. They agreed to pay £8,000 per annum – £4,000 by each for 5 years – on condition that the passenger tax was dropped and that the accommodation to be afforded should be separate and free of charge but the Board of Trade rejected the offer. Representing LCDR on the Board was James Staat Forbes who had been approached by DHB Board member, Samuel Metcalf Latham, the local Liberal Party Chairman, to stand in the next parliamentary election for Dover which was expected to be held approximately four to five years time. Forbes centred his manifesto on the harbour, saying that if elected he would help to make the port of Dover great and a Harbour of Refuge that the town had been calling for. In the event a by-election was called in 1873 but Forbes lost to the Conservative representative.

Following the General election of February 1874 the new Conservative administration referred the proposal to a Parliamentary Select committee. They advocated a larger scheme and a Bill was submitted to Parliament in December and estimated to cost £1,600,000. The new proposal, on government initiation, was placed in the hands of the Board of Trade’s two representatives on DHB, to pilot it through the Committee stages. In June 1875, the House of Commons Select Committee gave its approval. However, on Tuesday 13 July, in the House of Lords, Charles Henry Gordon-Lennox, 6th Duke of Richmond (1818-1903), on behalf of the government, announced that the proposal was to be, in essence, put on hold.

On 1 January 1877, there was a terrific storm at Dover that damaged the thinnest part Admiralty Pier – the centre curve of the parapet that was 5-feet 6-inches wide. Shortly after it was replaced by a 12-foot parapet with the stone facing filled in with concrete that is still in situ today. Dover builder, William Adcock (1840-1907), who had completed the later work on the Admiralty Pier, undertook the repair of the upper galleries.

Edward Prince of Wales c1890 Later Edward VII (1901-1910)

In June that year Trinity House, of which the fraternity of the Cinque Ports Pilots belonged and presided over by HRH the Prince of Wales (later Edward VII 1901-1910), held a banquet in London. The Lord Chief Justice of England, Sir Alexander Cockburn (1802-1880) gave the toast in which he said that ‘Trinity House was still busying itself keeping up our lighthouses and endeavouring to make the coasts dangers as trifling as possible. He only wished that the work of constructing harbours of refuge all round our coasts would be intrusted to Trinity House. … He had understood that … the construction of one at Dover … the Treasury has prevented it. The harbour of refuge was still, however, work that remained to be accomplished, and he hoped that heaven would permit him to live so long as 20-years to see it begun … if not put off again!’ He died three years later.

In the House of Commons, one of Dover’s two Conservative MPs, Charles Kaye Freshfield (1865-1868 & 1874-1885) strongly put the case for a harbour of refuge. He pointed out that it was of national importance ‘that the Strait of Dover, through which a large proportion of the nations commerce and navy had to pass and where the country’s ships of war could best wait in ambush should there be a need, should be completed.’ (01.06.1877) In the Lords, the Earl of Granville was loudly banging the same drum but on 26 March 1878, the Prime Minister, Benjamin Disraeli (1804-1881) 1st Earl of Beaconsfield, responded in Lords. His speech was so sarcastic that it was generally understood that while he was in power, a harbour of refuge at Dover would not happen.

Hopes that Dover would become a National Harbour Of Refuge were at a low ebb. Albeit, international events were coming into play as Part 2 of the Harbour of Refuge recounts.

- Presented:

- 15 August 2014