Dover Museum is one of the many jewels in Dover’s crown. Housed in a spacious building behind a Listed older, grand, façade it is here that the world famous Bronze Age Boat is on show. A must see attraction during even the briefest visit to the town. The museum gives an overview of the town’s history that whets the appetite to see more of the many historic gems the town has to offer. To help with this, the Tourist Information office is situated on the ground floor.

The history of the museum itself goes back two centuries, for it was during the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), that the idea of a town museum was sown. At the time, there was an influx of military and naval personnel, which had led, on the one hand, to a major growth in the entertainment industry such as theatres, assembly rooms for dances and balls and pubs etc., on the one hand, an interest in intellectual pursuits. One such organisation was the Dover Philosophical Institute whose remit was the ‘promotion of literary and scientific knowledge.’ In February 1835, Dover Corporation managed to gain possession of the Maison Dieu in order to use it as a replacement Town Hall and Law Courts. The council and courts, at that time, met in the ancient Court Hall in Market Square.

The galleries underneath the ancient Market Square building were used for a market but following the move, the council let the upper storey to the Philosophical Institute for £40 per annum to be used as a museum. Under the guiding influence of the Mayor, Edward Pett Thompson (1802-1870), who donated a valuable collection of 470 specimens of vertebrate zoology, including 420 stuffed birds and 50 fossils; it was formerly opened on 26 August 1836. The new museum was only open to members of the Institute with the intention to provide a library and reading room for conversation and classes.

Ordinary members of the public showed interest so to test the water, on Boxing Day – 26 December – 1836, the Institute opened the doors to the general public for five days. 1,500 people came and it was reported in the Dover Telegraph that, ‘the hall was so crowded that not all could sign the visitors’ book.’ Because of the interest the building was renamed the Dover Museum and in December 1837 it was announced that, ‘ The Museum would be open every Monday to all classes gratuitously!’

Earlier that year, in February 1837 a wild hog, killed in the forests of Germany, was presented to the Museum. This was the first of many such donations. It was reported that when Mr Gordon of Canterbury Museum skinned the hog, a bullet was found in the loins and several swan-shots in various parts of the body, over which the skin had healed. Albeit, of particular interest at that time, underneath the bristles and close to the skin was a kind of woolly hair not found in hogs elsewhere.

In September 1837, the Corporation Market Committee bought the town gaol and the land on which it stood, adjacent to the Market Square, for £555 from Dover magistrates. This left very little in their budget to build an intended market hall so the council sold the site to a private purchaser for more than was paid for it. However, on 20 January that year, the new Dover Police Force had been formed and they required a police station and lock-up. Thus, the site was repurchased but at a loss!

Time passed and a new prison and police station was built adjacent to the Maison Dieu and by 1845, the council was able to repurchase the site. That year saw the passing of the Museums Act that empowered boroughs with a population of 10,000 or more to raise a ½d rate for the establishment of museums. Dover decided to have a municipal museum and commissioned a report from architect, Mr Woodthorpe for a Market Hall that included room for the museum.

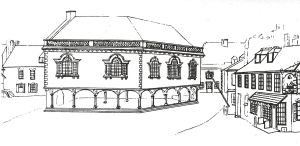

Mr Woodthorpe presented his report in April 1846 and the plans showed, ‘an open market with stone piers and arches above, subdivided in the interior by columns of a Tuscan character, comprising of a Museum along the whole front and above the centre of the Market, the exterior having Corinthian columns, the interior space being filled with pedimented windows.’ (John Bavington Jones: A Perambulation of the Town, Port, and Fortress of Dover. Dover Express 1907 pp 35.

The project was estimated to cost £3,000 and this was set aside. Ten builders tendered, seven from Dover, but all gave estimates greater than that budgeted. This was due to the cost of the Caen stone and the ornamental work. In the end, it was agreed not to use Caen stone and to cut back on the ornamental work and the lowest tender, from local builder George Fry, was accepted. The eventual cost for the building was £3448.

On completion the museum moved from the old Town/Court Hall into the upper storey in January 1849 and the old building was eventually demolished in 1861. The new premises consisted of a large gallery devoted to stuffed animals and birds, all carefully classified. There were also three smaller rooms, used for administration, lectures and talks etc. Admission was free on weekdays except Thursdays and was open for six hours a day.

Lectures and talks were on a variety of subject. Fir instance, on 25 March 1851 a Mr Mottley gave a talk on ‘The Electric Light’, which he illustrated with experiments using a powerful battery. Later that year, water, tea, coffee, cocoa and sugar were examined during a talk on ‘The Chemistry of the Breakfast Table’. That year local taxidermist Charles Crudden, who undertook much of the museum work, was awarded bronze medal at the Great Exhibition in London, for a case of ornithological taxidermy depicting the ‘mobbing of an owl’. In summer, nature rambles were organised and there were soirees and discussion groups that put both Dover and the world to rights!

Edward Rice, Liberal MP for Dover 1837-1857, who successfully petitioned for official papers and reports to be made available to the public through places like Dover Museum. Dover Museum

In the House of Commons in December 1852, Dover MP (1835-1852), Edward Royds Rice (1790-1878) asked for reports relating to arts, manufactures and commerce, to be made available to bodies such as the Dover Philosophical Institute. This was so that they became easy accessible in places such the museum and similar places throughout the country. The proposal was eventually accepted. In February 1860, the Dover Philosophical Institute petitioned the House in favour of the budget that year – especially the remission on the duty paper duty – Dover, at that time, had a number of paper mills.

The Mayor in 1854 was James Poulter and when Dr. Plumley of Maidstone offered his collection of fossils found mostly in Kent, the Mayor and the council gladly accepted them. However, the museum did not have the room in the main gallery to display them so the room previously used for lectures, talks and discussions was cleared to make room. Later that year the Mayor Poulter gave a dinner at the Ship Hotel on Custom House Quay. There Dr Plumley was presented with an illuminated address in recognition of his munificence. At about this time excavations were being undertaken on the former Priory site, now Dover College, where Roman pottery and cinerary urns were found. These too were displayed in the museum taking up the second of the three smaller rooms and lectures and talks were moved to a new venue.

The museum was severely damaged by violent thunderstorms in early September 1871 and a number of artefacts were damaged. National museums offered to care for Dover’s precious historical records until repairs were undertaken. Although local historians expressed concern that they would not be returned reassurances to the contrary were, apparently, given. Albeit, when the building was eventually repaired the precious documents were not returned.

Nonetheless, tourist guides were positive about the museum’s collection of stuffed animals, birds and the large Sloper collection of mounted and labelled butterflies. Roman artefacts as well as numerous Indian, Chinese and Burmese curios were given as attractions. Also listed, in an 1890 guide, are ‘ancient remains from Ninevah and Egypt’. These included a mummy-case richly decorated with a mummy inside. At this time, the museum was under the direction of local philanthropist Dr Edward Farrand Astley (1812-1907).

In 1894, a Captain Lang gave the Cesar, a Man o’War model made of bone. This was, and still is, of local interest for it is said to have been made at Dover Castle by a French prisoner. Now subject to dispute, traditionally, it is said that it was made during the Napoleonic Wars out of the bones left over from food rations. Apparently, the prisoner who was making it had not quite finishedwhen the Peace of Amiens was signed in 1802, so he remained at the Castle. By the time he has finished the ship war had begun again and the prisoner had to remain in the Castle for another ten years!

The hon. Walter Rothschild (1868-1937) presented a collection of stuffed mammalians to the town in 1901. To house them the museum and market hall were extended at the back in to Queen Street. The Mayor at the time was chemist, William James Barnes (c1850-1942) and he succeeded Dr. Astley as the hon. curator of the museum and librarian. The Rothschild collection, together with other items on display, regularly drew visitors from both home and abroad. Of particular interest was a parrot-feather cloak from Hawaii that had belonged to Kamehameha the Great (1758–1819) and presented to Wingham born General William Miller (1795–1861). He had participated in several South American revolutions before becoming the British diplomatic Consul to the Pacific Islands from 1844-1859.

Other items that attracted visitors was the head of a Maori chief, Oliver Cromwell’s (1599-1658) sword and a collection of rats dressed up as a skiing party together with a collection of stuffed kittens made to look as if they were drinking tea. Both were put together by local taxidermists of which there were several in the town at the time. There was also a bottle holder that had held the brandy used to try to revive Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) after he fell at the Battle of Trafalgar (1805), or so it was said.

However, local historians were becoming increasingly angry over the lack of interest in the loss of the town’s ancient records to national museums. The editor of the Dover Express, John Bavington Jones, who was also an amateur historian, spelt this out in a letter to the Times of 9 September 1912. He wrote, that a large portion of Dover’s minute books and a greater part of the original plans for Dover Harbour of the Tudor period were in the British Museum along with records of Dover Castle. That the ancient striking clock made in 1346 for Dover Castle and having the earliest form of casement, had been moved to the Victoria and Albert museum against the wishes of the people of Dover.

Bavington Jones went on to point out that in 1878, a five-coil torque was dug up during the excavations for the building of Castlemount. The torque was described as the finest armlet discovered in England and had been sent to the British Museum for verification but was never returned to the town! (A replica can now be seen in Dover Museum). Finally, he wrote, the MSS relating to St Bartholomew’s Hospital, Buckland, and compiled in 1373 was sent to the Bodleian Library, Oxford for safekeeping while the museum was being repaired. When he made inquires, the staff at the Bodleian did not know where it had been put!

On 30 April 1917, during World War I (1914-1918), a new curator, Frederick Peter Abbott, was appointed with a salary of £100 per year plus war bonuses. In December 1918, he wrote to the council pointing out that it had been agreed to increase his salary by £26 and from 1 January 1918 receive a war bonus of 10s per week but this had not happened. In his letter, the curator pointed out that the number of visitors to the museum during the quarter ending 30 September 1918 was 9,876 while in the corresponding quarter of 1917, there had been 9,588. It does not appear that his letter met with any sympathy for the council only recommended that the museum should close at 16.00hrs on Wednesdays, to save electricity!

Against increasing cutbacks, Mr Abbott struggled to keep the museum going. He even managed to add what was later described as a ‘fine collection of pictures, prints and books.’ However, visitor numbers were falling and there was a danger of the museum closing down. The National Museum Association visited and they were not kind about its state and recommended that Frederick Knocker (1858-1944) should be employed for a two-year experimental period to sort things out. The son of a local man, Knocker had a life long experience of museum work.

In August 1931, Knocker presented his report in which he said that the building was unsuitable, dank and cold. Due to lack of interest by the council both prestige and moral were low and the cases of exhibits were ‘odd shapes, sizes and of doubtful utility’. He recommended the disposal of many of the more dubious specimens. In addition, he noted that the staff consisted of Mr Abbott – whose salary had been increased – an exhibitor who was paid £156 a year, an attendant paid £52 a year and, on occasions, a charwoman who dusted and washed the floors.

On receipt of the report, the council proposed to increase spending from £500 to £2,000. A year the scheme, outlined by Knocker to revitalise the museum, was considered in September 1931. This was sent to the Carnegie Trustees in the hope of getting a large grant towards the cost of implementation. While awaiting a reply and under Knocker’s direction, the exhibits were thoroughly overhauled and the building cleaned and redecorated.

The showcases were placed where there was abundant light so that the contents could be seen and two of the small rooms were devoted to exhibits of a local nature. However, the Carnegie Trustees only granted £150 and that was to be matched by an equal amount from the Corporation. On appeal, the Trust increased the award by a further £100, again to be matched, but stipulated that the whole amount was to be used to provide an extension for the zoological wall cases.

Accordingly, in 1933 the museum and market hall beneath were enlarged. A tender of £1698 was accepted from Messrs Herbert Godsell of Maidstone for building work and one of £355 for an electric heating system from the Arora Company, of Loughborough. It was proposed by the council to charge only ½p per unit of electric heating current when the ordinary heating rate in Dover was 1½d.

Carnegie Trustees responded by giving a further grant of £2,000 for museum works and upgrading of facilities. The new look museum was opened by Dover’s MP (1922 -1945), Major the Hon. John Jacob Astor (1886-1971) on 4 May 1934. Although local history and archaeology were given as the main features, the first exhibition was designed to attract national attention and centred on photographs of Mount Everest provided by the Times!

To coincide with the opening a proposal was submitted to the council for the formation of a Friends of the Dover Museum Association. The objective was the raising funds by subscriptions and contributions ‘for the provision of modern casework and efficient maintenance and preservation of specimens.’ It was suggested that the minimum annual subscription should be 5shillings and that members be entitled to free copies of the museum’s publications, privileged admissions to exhibitions and lectures etc. However, the council refused instead they gave instructions that three additional collecting boxes were to be fixed at suitable places in the museum!

By now acting curator, Frederick Knocker forcibly suggested the establishment of a learned society for stimulating public interest in the museum by exhibitions, lectures etc. The council agreed but due to the lack of room, Knocker suggested turning part of the recently vacated Biggin Hall into a lecture hall accommodating 120 people.

The council refused but the first lecture went ahead on 5 January 1935, given by John Mowll at the Art and Technical school on Ladywell. The number of people who turned up was greater than the capacity of the facilities provided and with each subsequent lecture interest continued to grow. Eventually, the council relented and turned part Biggin Hall into a lecture hall accommodating 120 people.

Having formed an embryonic Friends of the Dover Museum Association in all but name, in April that year Knocker suggested a scheme to affiliate public museums in Kent with the view of pooling scarce resources to provide for a museum service in rural areas. This was placed before the Kent County Council Education committee, the Joint Committee of the Museums Association and the Carnegie Trust for their approval and financing and, it would appear, approval was given.

Mayor Alderman George Norman opened the Centenary exhibition of the founding of the Dover Museum on 31 July 1935. This coincided with National Navy week, so the event centred on a Naval and Maritime exhibition and the Dover Patrol during World War I. Artefacts included several items appertaining to relics from the Vindictive and the Zeebrugge Raid lent by the then Admiral of the Fleet Sir Roger Keyes (1872-1945)

The following day, in another part of the museum, Mayor Norman opened a six-week exhibition commemorating the Silver Jubilee of the ascending to the throne of George V (1910-1936). This was organised by John Mowll and included autographed letters written by Queen Victoria and chief Ministers of her reign. There were medals, coins and stamps of the preceding 100 years together with pamphlets and books connecting the Royal family with Dover. Both exhibitions were a great success attracting people from all over the country and from abroad.

In 1938, Frederick Knocker resigned and eventually a Mr Warner was appointed. World War II (1939-1945) broke out on 3 September 1939 and the period immediately following, often referred to as the phoney war, saw an increase in visitor numbers. Indeed, on 28 November 1939, the new curator congratulated the council for the ‘conversion of a dump into what you see to-day’. However, as the war progressed and danger became closer, Mr Warner asked the council if he could move items into caves for safe storage. The council’s priorities lay elsewhere, but as space became available, Warner moved precious town records that were still retained in Dover and local history books to safety.

On Monday 21 October 1940 at 12.50hrs, four bombs were dropped on the town. One hit the rear of the museum/market hall, damaging the building. No warning had been sounded but luckily no one was hurt. Following this Warner moved more items to safer places. The building was hit again on 23 March 1942 and afterwards, it was said, pieces of a mummy’s shroud fell all around the town! However, about 70% of the remaining collection was destroyed. What remained was quickly moved to caves, the Congregational Church and Sunday school on Russell Street and empty houses.

The Plomley collection of Kentish birds, including specimens that were, by this time, extinct were moved to empty houses, but the new locations proved to be damp. Until another ‘home’ could be found the collection was moved back to the museum. During further shelling of the town on 4 October 1943 the Plomley collection was destroyed and the museum building was finally abandoned. Then on Thursday 23 December 1943, a shell hit the Russell Street Congregational Church and most of the exhibits stored there were lost. Frederick Knocker died age 70 on 28 January 1944. He had lived away from Dover for many years but helped to prepare the museum’s war damage claim.

The Plomley collection of Kentish birds, including specimens that were, by this time, extinct were moved to empty houses, but the new locations proved to be damp. Until another ‘home’ could be found the collection was moved back to the museum. During further shelling of the town on 4 October 1943 the Plomley collection was destroyed and the museum building was finally abandoned. Then on Thursday 23 December 1943, a shell hit the Russell Street Congregational Church and most of the exhibits stored there were lost. Frederick Knocker died age 70 on 28 January 1944. He had lived away from Dover for many years but helped to prepare the museum’s war damage claim.

On Tuesday 26 September 1944 more than 50 shells were fired at the town, this was the last day of the four-year bombardment. When the shelling ceased it was estimated that the war damaged sustained by the town was proportionally greater than any other town in the country. A reconstruction plan had already been drawn up but to give it weight town planner, Professor Abercrombie (1879-1957), was appointed and his report was published in January 1946. Among his many recommendations was that in the middle of the town, between Brook House and Maison Dieu House, would be a Civic Centre. The two ancient Houses, both damaged due to the war and years of neglect, were to be repaired and protected. Brook House was to be refurbished as museum and Maison Dieu House was to become the town’s library.

Following World War II what remained of the museum’s artefacts were moved to the basement of the then Town Hall or stored in the tower. AS

Following the War, what remained intact or could be repaired of the museum artefacts were moved the bowels of the Maison Dieu, the then Town Hall. The remainder was put in storage in the Tower above the Town Sergeant’s office. The collection of town archives and local books were removed to the town library, in anticipation of the move to Brook House. In 1947, the depleted collections of artefacts were enhanced by the bequest of Lady Anne Cory’s collection of Victorian furniture. About the same time ceramics were acquired. Two years later Miss S Minet of Hadham Hall, Little Hadham, Hertfordshire, presented to the Corporation a collection of 20 framed prints and water colours of old Dover that initially were displyed in the Stone Hall of the Maison Dieu before been put into care of the museum.

After much deliberation the council agreed to convert Maison Dieu House into a library and to move the occupants, the Borough Engineers’ Department, to Brook House. The museum artefacts were to remain in the basement of the Maison Dieu, the tower and the library. To give the appearance of a respectable town museum, in February 1949 it was agreed to the widen the doors to the basement, in Ladywell and to insert the oak doors from the war torn St James’ old Church. The letters ‘MUSEUM’ was carved above the entrance and on 28 November 1949 the ‘new’ Museum was officially opened by the Mayor William (Bill) Fish.

From the outset, the premises were far from adequate and such items as the Hawaiian parrot-feathered cloak was sold to James Thomas Hooper (1897– 1971). He was a collector of ethnographic artefacts. Other artefacts that no one was interested in, such as a large stuffed black bear were kept. It was to spend the next few years at the bottom of the spiral staircase leading to the Tower, spooking unsuspecting visitors!

Across town, on 7 January 1951, the Bench of the Barons of the Cinque Ports was moved from the war-damaged vestry of the old St James Church, repaired in the Dover Harbour Board workshops and dedicated in St Mary’s Church. Due to lack of room in the museum, it remained in the church for the next few years. It is now on the third floor of the museum, where it can still be seen.

In 1956, for the first time since the war, the museum was mentioned in the Dover trade directory as a place to visit but the location was stated as Market Square! It was another three years before that was rectified. Francis McQueeney took over as museum curator in 1960. His special interests were silver, ceramics and military history and shortly after arrival a collection of cap-badges were on display at the museum along with war relics. He was also interested in transport and added a collection of bus tickets. However, McQueeney’s main aim was to bring people, from small children to old age pensioners, into the museum and one of the main attractions arrived shortly after Mr McQueeney!

Following the death of Dr Maurice Koettlitz, of Charlton House, London Road, on 6 February 1960, a polar bear that had been shot by his grandfather, Dr Reginald Koettlitz (1860-1916) was donated to the museum. The bear met its end while Dr Koettlitz was on the 1894 Jackson-Harmsworth Polar Expedition however, the good doctor is better remembered for accompanying Captain Scott on his Antarctic Expedition in 1901.

On returning to Dover, Dr Koettlitz donated clothing, skis, snowshoes and medical bag to Dover Museum while the bear was stuffed and fitted with a lamp holder in its paw. It then was placed in the surgery waiting room. Having no room for the smaller black bear, the huge polar bear posed a dilemma until McQueeney placed it as a doorstop at the museum entrance. It quickly acted as magnet to Dover children, including our own. It is now on the first floor of the museum in a glass case and proved a great favourite to Prince Charles on his visit in 2000!

During the 1960s, the increasing problem of lack of space led to a major clear out of exhibits, particularly those that were beyond repair. Those that could be salvaged and were of relevance to Dover were kept or lent. Everything else was sold or given away. Nevertheless, artefacts kept on coming in, such as a Maori carving in 1963, bequeathed by George Tulloch, a transport director. Some of those dispensed with have since been returned to the museum and restored but there were regrets. For instance, the Hawaiian parrot-feather cloak that belonged to Kamehameha, given to the museum by General William Miller and sold in the late 1940s fetched £140,000 at auction in June 1977!

Work started on York Street dual carriageway in the late 1960s and included the demolition of buildings, some dating from Tudor times. The road, it was envisaged, would relieve the town centre from traffic going to the docks. Dover Corporation, on the insistence of the New Dover Group (now Dover Society), contacted archaeologist Brian Philp of Kent Archaeological Rescue Unit (KARU). Philp with his team of archaeologists and local volunteers excavated and uncovered what turned out to be the richest 15 acres of buried history in Britain.

This included many large, exceptionally well preserved, Roman buildings that made up the Classis Britannica Fort. The Roman Painted House is recognised as the best-preserved building of its type north of the Alps. The archaeologists also discovered considerable amount of Saxon artefacts and the early history of St Martin-le-Grand Church. For his work, Brian Philp was awarded the M.B.E in the Queen’s Birthday Honours list, 2013.

The 1972 Local Government Act led to the formation of Dover District Council (DDC) on 1 April 1974. Once again, consideration was given to Brook House being converted into a museum. However, the idea was put on hold until new district council offices were built but eventually Brook House was demolished to make way for a coach park for visitors to the ill-fated White Cliffs Experience (WCE). As a consequence of Local Government reorganisation Dover’s library came under Kent County Council (KCC) and with this, the ownership of Dover’s books and records were transferred to KCC. Local access was maintained in the Local History room in Maison Dieu House with a specialist librarian in charge.

Mr McQueeney retired in 1978 and died the following year. Sarah Campbell, the town’s first professional curator, succeeded him and she instituted a determined change in museum policy. The emphasis was to be on the history of Dover and the surrounding area. This was given major impetus that year when in Langdon Bay, Dover Sub-Aqua Club divers found what they believed to be dumped were rail wedges.

The wedges were examined by the marine archaeologist, Keith Muckleroy (1951-1980), who identified the wedges as Bronze Age median-winged axes and within three days, a protection order on the site was issued. Eventually a rich haul of 280 bronze age pieces were recovered that included axe heads, jewellery and rapiers but there was no sign of a ship. That year, KARU archaeologists working within the grounds of Dover College, found flint implements some 4,000-year-old.

In 1982, Cllr. Peter Mee put forward the idea that the old prison cells under the then Town Hall, should be opened up to the public as an extension of the existing museum. As some of the cells still had gaslight installation, he suggested that they could have waxworks figures within wearing prison uniform. He pointed out that the slate ablutions and the police station sergeants’ desk still remained and could be used as part of the exhibition. Cllr. Mee’s idea not long after became the very popular ‘Old Town Gaol’ visitor attraction that was closed in 2000 and sadly missed.

Ms Campbell moved to Northumberland in November 1983 and was succeeded by Christine Waterman the following February. Her first exhibition was on the town’s malting industry. Ms Waterman, in 1987, instituted the re-launch of the Friends of Dover Museum, to promote the activities of the museum and the history of the area in general for which DDC gave a grant of £300.

A ‘Heritage Centre’ idea for Market Square was put forward in 1987 by DDC consultants Hillier Parker, hired by DDC. In November, following the consultants advice, John Clayton, the Director of Planning and Technical Services, presented the ‘Roman Heritage Centre’ scheme that cantered on displaying many of the archaeological finds in the previous 20 years. The project was to be in-house as part of a Market Square redevelopment programme that would have a common entrance where a tourist information office would located.

This, it was envisaged, would encourage visitors to local historical sites. These included: the Castle, Roman Painted House, Roman Invasion Sites at Deal and Walmer, Richborough Castle, St Mary’s Church, Barfrestone Church, the remains of St Martin-le-Grand, the Knights Templar Church on the Western Heights, Archcliffe Fort, Mote Bulwark, Admiralty Pier Turret, Dover Patrol Monument – St Margaret’s Bay, Langdon Cliffs to view Eastern Docks, the Maison Dieu, St James ‘Old’ Church and St James Cemetery. As well as the memorials on the Seafront, other Cinque Ports including Sandwich and World War II sites such as Hawkinge and Manston. The nucleus of this grand scheme was the ‘Roman Heritage Centre’ and museum that Dover could be proud of. The expenditure was estimated at £20m.

At about this time the Kent Building Preservation Trust identified 15 properties that were endangered by decay. One of these was the derelict old market hall/museum, the façade of which was Listed. This tied in neatly with the Clayton project and the council gave permission to create the three-storey ‘Roman Heritage Centre’. With the close collaboration of Brian Philip and KARU, work started. With the change of policy, DDC commissioned a report from the Area Museums Service for South East England on the potential of Dover’s museum as a tourist attraction.

In their report, published in May 1988, the Museums Service noted the chronically cramped conditions with poor access and low staffing levels of Dover’s museum. They made a number of recommendations that resulted in a restyling of the museum service for the development of heritage-based tourism. The ‘Roman Heritage Centre’ idea gave way to the creation of the White Cliffs Experience adjacent to which would be a purpose built museum the interior of which was designed by Ivor Heal.

In 1989, the museum started the move into a new build that retained old market hall/museum the façade. Utilising many of the contents from the old museum, the presentation in the new museum was carefully considered to provide interest at a variety of levels from young children and tourists from abroad to local historians and academics. However, it did not include a tourist information office or any reference to the work of KARU and the Roman Painted House.

In March that year, ‘Historic Dover’ information boards went into production and were erected throughout the town and District. In Dover, a leaflet provided an easy to follow trail for Dovorians and visitors alike. Designed in-house and produced by a Dover sign maker, the text was written by museum staff and checked by local historians Ivan Green and Joe Harman and by members of the Committee of the Dover Society.

On the instigation of the District Auditor, a collective management policy for the District’s museums was considered. This was in order to facilitate grants under the National Registration Scheme for Museums but required staffing levels etc. to comply with a set standard. The recommended museums included Dover museum, the Old Town Gaol and the Grand Shaft that goes from Snargate Street to what once were the barracks on Western Heights. Dover museum was registered under the scheme.

At that time, I was undertaking an intensive piece of academic research into high street banking, which started in Dover. This culminated in the academically successful book, Banking on Dover (published 1993). Throughout my research, Ms Waterman and her team was very helpful, particularly assistant curator, Mark Frost. Mark was involved in putting on a number of successful exhibitions at the museum appertaining to the locality. Typically, in 1998, there was an exhibition on the history of Channel Swimming centring on 400 photographs that had been donated to the museum. There were also artefacts such as Ethel (Sonny) Lowry’s swimsuit – she successfully made the crossing in 1933. It was a sad day when Mark left the museum.

The museum and the White Cliffs Experience next door were officially opened by Princess Anne in 1991. At the time, the A20 from Capel to Eastern Docks through Aycliffe and following the line of Snargate Street and Townwall Street was being laid. It was recognised that once completed the busy road would effectively cut the town of Dover from the Seafront, so a wide underpass was to be built from Bench Street to New Bridge. To try and ensure that the underpass would be a pleasant concourse the Highways Agency (the Highway Authority for Trunk Roads) together with their design consultants (Mott MacDonald) and the staff of the museum came up with a decorating scheme detailing the history of Dover.

Bronze Age Boat discovered while excavating for the A20 underpass September 1992. Thanks to Nick Edwards

During the excavations for the new road, archaeological surveys were undertaken by Canterbury Archaeological Trust led by Keith Parfitt. In autumn 1992, work started on the proposed underpass and on the morning of 28 September Nick Edwards, operating a Caterpillar excavator for the contractors Norwest Holst, uncovered what turned out to be a Bronze Age boat – believed to be the worlds oldest known seagoing vessel was unearthed by the archaeologists!

Dating from 1550 BC it is about 18-metres long, 3-metres broad and it was immediately recognised as of international importance. Constructed of oak planks it is joined together by a complex system of wedges, timbers and ropes a crew of sixteen paddlers probably propelled it. The Boat was in operation before the Egyptian ruler Tutankhamun was born, and when the Romans arrived in Kent the coastal silt had already buried it for 1,600 years!

November 1999 saw the official opening of a specially constructed gallery on the top floor of the museum by Robert Leigh-Pemberton, Baron Kingsdown, and Lord Lieutenant of Kent (1927–2013). The exhibition in the gallery housing the Bronze Age Boat explains how experts saved the craft after it was discovered what it was used for and how it looked like at the time it sailed. By this time, the White Cliffs Experience was proving a financial liability and closed on 17 December 2000. It was hoped that the 3,600 year-old craft, among the best-preserved vessels of its type in the world, would go some way towards attracting the visitors that the White Cliffs Experience failed to do. It is certainly doing just that and rightly so.

In the 1999 Queen’s Birthday Honours List Ms Waterman, the museum curator received the M.B.E. and in this author’s opinion deserved it for ensuring that the Boat stayed in Dover. As yet, Keith Parfitt – the archaeologist who discovered the Boat – has not received such an award, hopefully he will. On 8 March 2000 saw Prince Charles touring Dover and environs on an official royal visit. His first stop was, naturally, to see the Bronze Age Boat at the museum. On his way down from the gallery, he came face to face with the Koettlitz polar bear, by then in a glass case on the first floor. ‘What an amazing creature,’ he exclaimed!

The following year, the museum undertook its first community-led project, centring on the old village of Buckland. Absorbed into Dover Borough in 1835, the village was famous for its brickfields, paper, corn mills breweries, blacksmiths and watchmakers. The church of St Andrew’s Buckland, is the only existing parish church in the town listed in the Domesday Book of 1086.

Not long after an historic art collection was acquired by the museum comprising of artworks, engravings, lithographs, photo’s prints, watercolours and sketches that depict Dover from the early 1720s to 1904. They were bought with a grant from the Victoria and Albert purchase fund plus a generous donation from a local benefactor. The collection included three watercolour and two pencil sketches by the town’s most important artist William Burgess (1805-1851)

Ms Waterman was promoted to head the housing department of DDC and was succeeded by Jon Iveson, the deputy curator. Among Jon’s many accolades is that he actively encourages the community and local historians to become involved in the museum and thus helping to ensure its survival. This quickly became evident when, in 2002, DDC’s policy moved rapidly away from tourism and the museum’s budget was cut by almost £200,000 a year and closure threatened. The White Cliffs Metal Detecting Club – many of whose finds are on display in the museum – and others, including this author, actively campaigned to reverse the decision. The Metal Detecting Club collected over 6,000 signatures on petitions that included representatives from the British Museum. Swingeing cutbacks were introduced but the museum survived.

Spring of 2003 saw the National Maritime Museum in Greenwich put on an Elizabethan exhibition and the painting of Elizabeth I (1558-1603), that had not left Dover since completion over 400-years before, was loaned by the Dover museum. Called, ‘Portrait of Elizabeth I with the Cardinal and Theological Virtures’, it is one of the few paintings of Elizabeth that is documented as specifically made for a civic environment. Following the exhibition, unlike all of Dover’s precious historic documents loaned to the country’s great museums in the past, it was returned to the museum.

The White Cliffs Experience building was sold to Kent County Council (KCC) for £1 and renamed the Dover Discovery Centre. 2003 saw the library move from Maison Dieu House to the Centre that included the Adult Education Centre and a theatre later taken over by the Blackfish Academy (theatrical). The local studies section of the library continued for a short while but a change in KCC policy from specialist to ubiquitous librarians meant the loss of valuable expertise in local studies. Initially, specialist expertise along with access to Dover archives that had been kept in the old premises of Maison Dieu House and County Hall Maidstone were to a small unit at Whitfield. After a few years, due to cut backs, it was closed making it difficult to access Dover’s ancient and not so old records.

The museum, on the other hand, has increasingly built up its library of local studies and the librarian, Bryan Williams, is a mine of information and very helpful. Albeit, the museum library, which is situated on the second floor at the front of the building, is long, high but very narrow. This means that the public are not able to access it.

On 20 July 2005, Queen Elizabeth II visited the museum to see the Bronze Age Boat exhibition. She was received by curator Jon Iveson and Admiral the Lord Boyce, Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports. She was introduced to the Mayors of the Cinque Ports and their officers and although she passed the Koettlitz polar bear, she did not react in the same way as her son did!

In 2005, Elizabeth Knott died at the age of 92. Her father, who had been an auctioneer’s clerk at Flashman’s in the Market Square, had acquired a collection of some 122 painting by Mary and Susanna Horsley. Also work of the Reverend Maule of St Mary’s Church. These, Miss Knott bequeathed to Dover Museum.

Together with Jon Iveson and with the help of Colin Friend plus the support of the Friends of Dover Museum, in January 2006, this author put on a six-week exhibition telling the story of Market Square. However, more financial cutbacks were imposed in December 2007, but the museum survived and continued to attract locals, students, schoolchildren, and tourists. In 2011, an EU ruling obliged local council taxpayers to pay an entrance fee, nonetheless they still come, especially to bring their visitors to see the Bronze Age Boat.

Tourist buses from cruise ships stop nearby the museum and in September 2012, the tourist information centre was relocated to the ground floor of the museum. The deputy Mayor, Ronnie Philpott and Chairman of DDC, Cllr. Sue Nicholas, officially opened it and the museum is a ‘must see’ for visitors to Dover.

Dover Museum and Visitor Centre: telephone: 01304 201066 or email tic@doveruk.com

Friends of Dover Museum

The Friends of Dover Museum, formed in 1987 to promote the activities of the Museum and the history of the area in general. They meet at 7.30pm on the third Tuesday in the month (except July and August) at the Baptist Hall on Maison Dieu Road. Enquiries: Dover Museum or friendsofdm@tiscali.co.uk

Finally, a special thank you to Jon Iveson – Dover Museum Curator – and Bryan Williams – Dover Museum Honorary Librarian – for their continued unflagging encouragement, help and support – You are great guys!

- Presented: 20.08.2014