The fraternity of Pilots belonging to the Cinque Ports has probably been in existence since before William I (1066-1087) conquered England in 1066. The main prerequisites to become a pilot, at that time and for centuries after, was to be a Freeman as well as having a thorough knowledge of seas, coasts and ports of the dangerous Dover Strait. The punishment metered out to a Dover pilot who lost a ship he was in charge of but survived, in those days, was to be thrown to his death off Western Heights!

In the Middle Ages there were three Societies of Pilots in England besides the ones appertaining to the Cinque Ports, these were at Deptford, Hull and Newcastle and were known as Trinity Houses. The Deptford Trinity House – chartered in 1514 – was in charge of providing sea-markers and signals that overtime developed into having the sole responsibility for British lighthouses and lightships. Each of the five Cinque Ports – Sandwich, Dover, Hythe, Romney and Hastings, along with the two antient towns of Rye and Winchelsea, had their own fraternities of pilots that came under the umbrella of Cinque Ports Court of Shepway.

In 1312, it was decreed that four Wardens, from among the pilots, were to be appointed in order to ensure that each pilot took his turn and to divide the fees according to the work done. By 1495, the Dover pilots, as within the other Cinque Ports, were governed by a set of tight rules that they were obliged to obey. However, on 20 May 1515, Henry VIII put the Cinque Ports Pilots on a more formal footing when he sanctioned by Charter, the Fellowship of the Cinque Ports Pilots or Lodesmen (meaning one who leads the way). In 1526, the then Lord Warden (1521-1533), Sir Edward Guilford (c.1474 – 1534), was approached by the Dover pilots to adjudicated internal disputes.

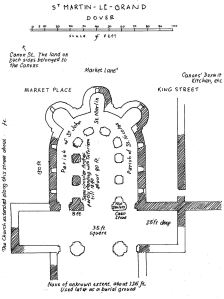

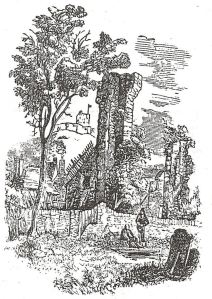

As the Lord Warden already presided over the Court of Admiralty, which met in St James’ Church – the ruin on Woolcomber Street – it was easy for him to extend his role and agree. The result was the Court of Lodemanage and on 26 February that year, 14 candidates stationed at Dover, one at Deal and two at Margate were licensed as Pilots – Deal and Margate were Cinque Port Limbs of Dover and therefore came under the jurisdiction of the port. The pilots from the other Cinque Ports were invited to join but declined and in consequence, the fraternity became known as the Fellowship of Pilots of the Trinity House of Dover, Deal and the Isle of Thanet.

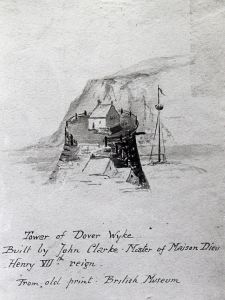

Wyke or Wick Tower – built by John Clarke in the 16th cent. From a British Museum print. Dover Library

The Court of Lodemanage thereafter was presided over by the Lord Warden and supported by a jury drawn from the Dover pilots. The position of the Warden Pilot was formalised and was usually held by the oldest working pilot. One of the regulations stipulated that half the money raised from fines paid by pilots for misdemeanours was to go towards the repair bill of Dover Castle, the other half to the repair of Martins Mill After the Reformation (1529-1536), the second part of the fine was used for the repair of the Wyke – a sea wall that protected the town. At the same time legislation decreed that all ships, except those with native masters and mates, had to use a licensed pilot to navigate the Channel, Thames and Medway estuaries safely to port.

Slowly the rules were tightened and by 1550, pilots had been divided into three classes. It was also agreed that members could choose their own substitutes regardless of which class they belonged. This led to abuse of the system so in 1567 the substitute, or ‘rear turn’ as it was called, was by a fixed order within the pilots’ class. Later, this was adapted to allow pilots who were too old or infirm to use substitutes in their place and in such cases, the infirm pilot was given a quarter of the fee and thus he was guaranteed an income.

In subsequent years the class structure was reduced to two – the Upper and Lower books with experienced pilots belonging to the Upper Book. They took charge of ships over 60-tons and the tonnage and draught of vessel determined the amount these pilots charged. The less experienced pilots belonged to the Lower Book and they piloted smaller vessels and vessels out of Margate or Ramsgate, as they were minor ports at that time. They would move, on a seniority basis, to the more lucrative Dover or Deal as vacancies arose when they were promoted to the Upper Book to fill vacancies. Each Pilot was self-employed and out of his receipts, he was obliged to pay a percentage to the Lord Warden.

A square-rig sailing ship has sails which are set athwart her masts such as this Circa 1780 Frigate.

To become a fully-fledged pilot, the candidate had to serve seven years as a Master Mariner and then take an exam. This involved carrying out soundings of the Channel from Amsterdam to Calais on the Continental coast and along the English coast. He also had to prove that he had the knowledge to navigate a ship through the Downs, up the Thames and Medway and to all Channel ports in all weathers. Later pilots had to spend a year as a navigator on a square-rigged vessel, a precondition that lasted up until 1939.

Once attaining the requisite standard to be admitted into the fraternity, the candidate had to undertake a formal ceremony. First, he was required to swear on the Bible that he would abide by the rules of the Court of Lodemanage. He was then given the ‘Branch’ – a piece of wood affixed with the Seal of the Courts of Admiralty and Chancery. On acceptance, he was then issued with a licence that included his physical description and his own pendent that was to be flown at all times he was in charge of a vessel. A grand dinner that included all the Cinque Ports pilots followed the ceremony, which took place at St James’ Church. The candidate paid for the whole affair.

In 1568 pilots started surveying the Channel from the South Foreland to the Nore in order to chart the ever- changing channels and sandbanks of the Goodwins. From 1590, this became an annual survey. However, throughout that time strife between the Cinque Ports Pilots and Deptford Trinity House Pilots existed as both were working the same stretch of sea, namely the Thames estuary. Pilots from Deptford were reluctant to disembark and allow the Dover pilots to take over a ship going down the Channel. While, Dover pilots took the same attitude against Deptford pilots that wanted to take over ships going up the Thames to London. Eventually, it was agreed that Trinity House pilots navigated ships outwards and Cinque Ports pilots’ navigated ships inwards.

In Parliament Dover’s MP, Sir Henry Mainwaring on the 27 February and 8 March 1621, opposed the Bill for the transferring of the control of lighthouses along the Kent coast from the Cinque Ports Pilots to Trinity House. Arguing that their knowledge of the coast stretched back further and was far was greater that of the Trinity House Pilots. However, over the next 100years subsequent Lord Wardens introduced rules governing the pilots at the same time taking a greater slice of the fees they earned. Nonetheless, in 1648 pilots invested £180 in buying a small estate at Heslingwood, Napchester, Whitfield. However, when the Lord Wardens started to insist that pilots should remain at sea all the time, master mariners became less interested in becoming pilots and the fraternity was in danger of collapsing.

Added to this, following the Restoration of Monarchy in 1660, those who were interested were refused entry if they did not belong to the Anglican Church. Church attendance was compulsory but up until that time dissension was tolerated. Matters came to a head in 1682 when it was decreed that all Cinque Port pilots found at a conventicle or dissenters’ place of worship were to be suspended (see The Dynasty of Dover – Part I – the Stokes).

In 1688, as a reward for helping William III (1689-1702), navigate the Channel prior to the Glorious Revolution that year, the pilots were given the right to choose four Wardens from their own body and to keep a greater percentage of the fees they earned. These Wardens were chosen from the Upper book and given the prefix title of Captain followed by the name of landmarks in Dover and Limbs. They were Captain of Mote Bulwark and the Captains of Deal, Walmer and Sandown Castles. The most senior Warden, by service, was also the Master of the Court of Lodemanage and in the absence of the Lord Warden, he fulfilled the position of judge.

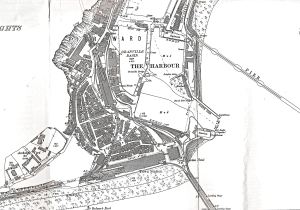

By this time, the Pilots had sold their Napchester estate and with the money purchased, in 1689, half an acre of land on the Western Heights.- later known as Pilots’ Field (now Pilots’ Meadow allotments). From there was a flight of steps that led to Snargate Street and the then harbour. Local boatmen, who berthed on the beach, would row the pilot to the ship. The navy dealt with any ship that refused to take a pilot on board.

In 1699, the compulsion for Cinque Ports pilots to be members of the Church of England was rescinded and at the same time they were given leave to build, for their own use, a gallery at the western end of the middle aisle of St. Mary’s Church. The front was elaborately adorned with their emblem and, if a ship was spotted, there was a staircase giving a quick exit into Cannon Street. Pilot’s galleries were also built in St. Leonard’s Church Upper Deal and St. George’s Church in Deal. Women were only allowed to enter these galleries to clean them but on no account were they allowed to sit on the pews!

During the eighteenth century overseas trade and in consequence shipping increased, this led to an increasing demand for pilots and it is recorded that in 1716, there were 50 pilots at Dover, 50 at Deal and 20 in Thanet. The following year saw the introduction of the Cinque Ports Pilotage Act (1717), this was the first parliamentary legislation covering pilotage. The Act stated, amongst other things, that it was inhuman to require pilots to remain at sea all the time. However, it revoked many of the privileges given by William III, notably the regulation that allowed the Pilots to elect their Master and Wardens. The Act was consolidated in 1724 and included further regulations.

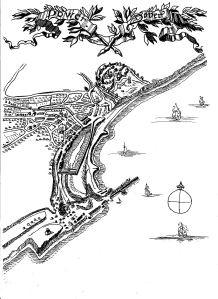

By 1730, a wooden Pilot’s lookout had been built on Cheeseman’s Head, (where nowadays Admiralty Pier leaves the shore) and Pilot’s Field was let out for grazing to raise money for Pilots’ pensions. Of interest, over a century later the Field had been renamed Pilots Meadow and was a favourite resting-place of Charles Dickens (1812-1870) when walking the cliffs. The Pilots cottages were on the seaside of Pilots Meadow and the senior Upper Case Pilot lived in the best one, which was described as having a double front and a small walled in garden. This is believed by many to be Betsey Trotwood’s home that Dickens described in the book David Copperfield as ‘A very neat little cottage with cheerful bow windows: in front of it, a square gravelled court or garden full of flowers; carefully tended and smelling deliciously.’

More regulations were introduced in 1735 including one stating that Dover pilots should regularly cruise between the South Foreland and the Red Fall – Folkestone, Deal pilots between the North and South Forelands and Thanet pilots in their own bays and south to Sandwich. In Dover, pilots were coming in for increasing criticism over leaving St Mary’s Church during services to pilot ships. In order to try to placate the congregation the pilots bought, in 1742, a chandelier capable of holding twenty-four candles for the church to match one bought by the parishioners in 1738.

Albeit, the complaints continued so the pilots sort legal action and on 20 October 1748, obtained a license for the gallery that allowed them to come and go as circumstances necessitated. In 1834, a plaque listing all those who served as pilots was erected in St Mary’s Church and the list was kept up until 1891. This was restored in 2002 and refixed in the South aisle of the church under the plaque commemorating the pilots that were lost in World War I and World War II.

Watch belonging to Deal Pilot Gideon Chitty (1739-1788). The face instead of numbers is his name. Adrian Chitty

The fraternity was close knit and gave pilots special personal awards. For instance, I have recently been sent photographs of a gold watch belonging to Deal Pilot Gideon Chitty (1739-1788). The gold case is beautifully elaborate and the inscription reads, Gideon Chitty 237 Bayly Deal Pilot’. However, it is the watch face that is of particular interest to the historian. Instead of the numbers 1 to 12 for the hours, it is the letters GIDEONCHITTY!

Towards the end of the century, it was becoming increasingly apparent that an age-old right of locals being allowed to conduct vessels without the need for a pilot was being abused. Merchants were making masters or/and mates of their vessels nominal partners and registering them as residents of an East Kent port. At the time an increasing number of these vessels were running into trouble on the Goodwin Sands. To make matters worse, once in trouble, the ships were not only vulnerable to maritime catastrophe but to the unscrupulous.

On 8 February 1805 the Endeavour, a West Indiaman, ran aground on the Goodwin Sands. Her cargo was valued at £23,000 and included rum, sugar and coffee. Peter Atkins, a Deal boatman offered the captain help to unload the stricken vessel, which was accepted. Whereupon Atkins allegedly called out, ‘A wreck! A wreck!’ and a number of Deal boatmen came aboard and unloaded the ship. However, an audit of goods landed showed that only £500 had been salvaged and Atkins was prosecuted for ‘felony and piracy on the high seas,’ a capital offence.

The case was tried at the Admiralty Court in the Old Bailey, London, and received a lot of publicity. Lady Hester Stanhope (1776-1839), the niece of the Prime Minister William Pitt the Younger (1759- 1806) who was also the Lord Warden (1792-1806), was the chief witness on behalf of Atkins. She stated that the Deal pilots, who were under the Dover Court of Lodemanage, made excessive charges such that many ships traversed the Downs without qualified pilots. In most weathers this was not a problem, however, in storms, ships could easily lose their way and be swept onto the Goodwin Sands and wrecked. Furthermore, while waiting in the Downs for Deal pilots to come aboard, left ships vulnerable to French privateers as well as changes in the weather. The Deal boatmen, she said, seeing these travesties were risking life and limb to help such ships for which they received only a small reward for the dangerous work they undertook.

Atkins was found guilty and sentenced to Transportation but before the trial had even begun Medmer Goodwin of the Ramsgate Commissioners of Salvage, had approached Lloyds of London suggesting that his firm should act as agents for the Insurance underwriters. The offer was accepted on 28 August 1811 when agents were appointed for 140 ports. For Dover, John Friend of Deal, an associate of Medmer Goodwin, was appointed.

Throughout this time, the Napoleonic wars (1793 to 1815) had been raging and the Cinque Port Pilots were heavily employed in a naval capacity both in the Channel and in sea battles elsewhere. On 9 August 1805, an attempt was made to invade England from Boulogne and Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) led a successful offensive. After winning a crushing victory at the Battle of Trafalgar, off southern Portugal, on 25 October 1805, Nelson died from his injuries and his body was brought back to England for burial. His ship, the Victory arrived off the South Foreland on 16 December and came into Dover harbour for shelter as a gale was blowing. She left on the 19th for Chatham with Edward Sherlock (1743-1826), a Dover pilot, at her helm.

An Act of Parliament in 1808 stated that Upper Book pilots were to take vessels over 14 feet draught and two cutters were to be established off Dungeness. On the cutters were rowing boats to take pilots to homeward bound vessels. The cutters, crew, provisions and rowing boats were paid for out of the fees that the pilots earned and the facilities on board the cutter were to be basic. By this time, the number of pilots at Dover had increased to sixty-four and four years later, in 1812, a widows fund was introduced into which every member subscribed 5s (25p). This entitled the widow to a yearly pension of £12 12s provided she did not remarry.

The 1808 Act was replaced four years later and the new Act comprised of much of existing legislation adding a new section that attempted to define the responsibility and rights of the ship owner, master, and owner or consignee of the cargo. This was in relation to any sustained damage to the ship, goods or persons that occurred through ‘neglect, default, incompetency or incapacity of any pilot taken under the provisions of the Act.’ The repercussion was confusion and litigation as the Act effectively granted absolute freedom from claims for any damage done to other vessels or property to ships while under compulsory pilotage. The Pilotage Act of 1824 caused even more strife by making it possible for non-British vessels to enter or leave British ports without pilots.

On 29 July 1824, bankers and Upper Book pilots, Sam Latham and his sons Henshaw and Samuel Metcalf, were appointed Lloyds (Insurance) Agents in Dover in place of John Friend of Deal. The office complimented their role in the Court of Lodemanage, where they were particularly concerned in the prevention of shipping accidents. The statistics showed that 1,117 vessels had been lost in the Strait of Dover for the three years 1816-18 and a further 89 were registered as missing. The number of vessels of which the entire crews had drowned was 49, amounting to the loss of life 1,700 persons. The following year (1825), an Act of Parliament stipulated that ‘not less than 18 Cinque Ports pilots should always be cruising, day and night, off Dungeness.’

In 1831 a third cutter was introduced for pilots based in Thanet but two years later, the House of Commons conducted an inquiry into the distress of Dover boatmen that had been displaced by the introduction of pilot cutters. In order to safeguard their living the number of pilots was limited to 56 each at Dover and Deal and 12 in the Isle of Thanet. The Cinque Ports Pilotage Bill of 1834 argued in favour of boatmen undertaking the work of pilots between the South Foreland and Dungeness. The Lord Warden (1829-1852), Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) fought hard against this and it was not sanctioned.

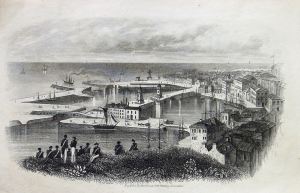

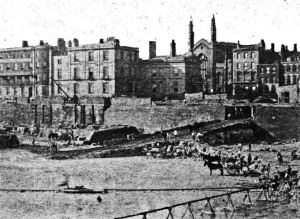

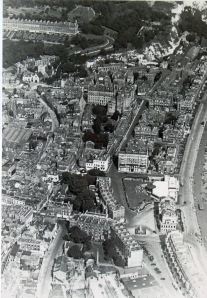

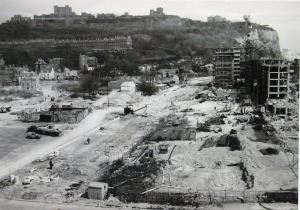

The following year a Royal Commission was set up to look at pilotage and the Pilotage Act of 1836 recommended the appointment of the Elder Brethren of Trinity House, Deptford, as the central licensing body but this was not implemented. At the time, the Cinque Ports pilots and the local shipping industry were more concerned with securing a Harbour of Refuge was needed between the Thames estuary and Portsmouth and did not realise that moves were being made to disband the Cinque Ports Pilots. Dover’s opportunity came to promote the case for a Harbour of Refuge in a Parliamentary Inquiry held in 1836 and the first result was a start being made, in 1848, of the Admiralty Pier. This was completed in 1871 and the final result is the harbour we see today that was opened in 1909.

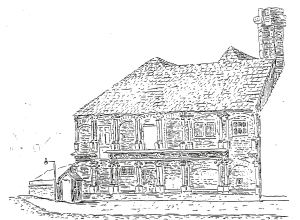

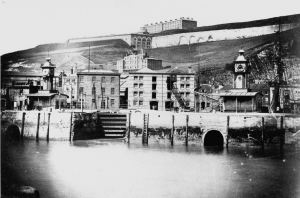

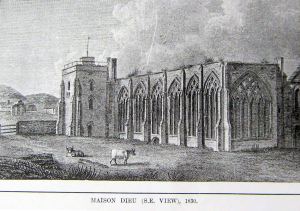

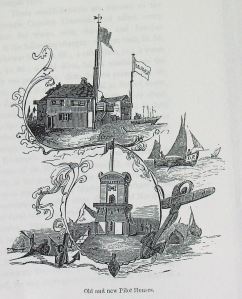

The ornate Pilots Tower that opened 1848 drawing shows old Pilots station that was on Cheeseman’s Head. Thanks to Evelyn Robinson

There was again a move, in 1843, to replace pilots with boatmen as, it was argued, pilots charged too much. Again, the Duke of Wellington resisted. That year saw 100 applicants applying to fill 27 vacancies for Cinque Ports Pilots. The ceremony for the making of the new pilots proved to be an anxious affair and it culminated with the rejected candidates, their relatives and friends besieged St James’ Church!

In 1844, to make way for the South Eastern Railway track, the pilot station was demolished on Cheeseman’s Head and a highly ornate station, built of stone and standing on a bed of concrete 10 feet thick, replaced it in 1848. Later, in 1864, three years after the London, Dover and Chatham Railway had arrived in Dover, both railway companies were allowed to extend their services along the newly finished Admiralty Pier and the pilots tower stood in the way. The ground floor, which had a ceiling height of 20ft (over 6 metres), was gutted to allow trains to run through it!

The Pilotage Bill of 1849 centred on disbanding the Cinque Ports pilots and their role being taken over by boatmen. One of Dover’s two Members of Parliament (1835-1852) was Edward Royds Rice (1790-1878) who argued that they should be retained. He pointed out that over the previous ten years the Pilots had taken 3,800 ships safely up the Channel and that in the whole of that period there had been only 14 complaints made. These, he said, were examined at the Court of Lodemanage and only six had been established leading to the dismissal of three pilots.

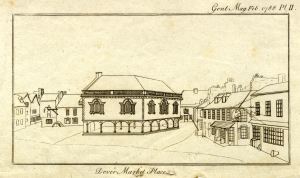

Albeit, the days of the autonomous Cinque Ports Pilots were numbered and they were transferred to the Trinity House of Deptford. This was ratified by Act of Parliament in 1853. The last Court of Lodemanage was held on 21 October 1851 and the town turned out to mourn. A procession, headed by the senior Warden – the Master of the Court of Lodemanage – followed by all the Pilots, including those who had retired, wearing their ceremonial blue coats and primrose waistcoats adorned with gilt buttons, marched from St Mary’s Church. There they had been blessed before going to St James’ Church. In the Admiralty Court a formal service was held and then, retracing their steps, the pilots went into the Antwerp Hotel that stood in Market Square, for a wake. Apparently, this lasted many hours and most of the pilots had to be carted home!

The story continues in Cinque Ports Pilots – Part II

Published:

Dover Mercury: 13 May 2010