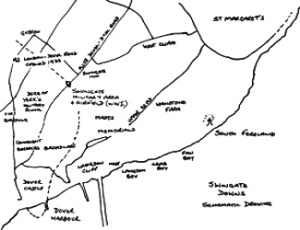

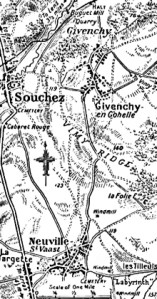

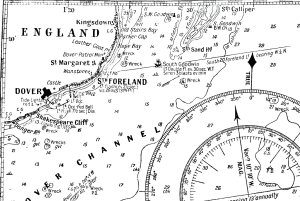

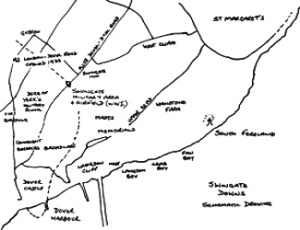

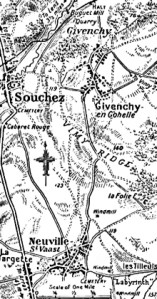

Map of the Swingate Downs Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty (AONB) – openstreetmap thanks to Protect Kent – Branch of the CPRE

Swingate is a large stretch of downland on the east side of Dover Castle. It is a designated Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty and the history of the site is internationally unique, particularly in relation to communication. This essay is the second in a series of four stories, told in chronological order, which gives a glimpse into this fascinating history.

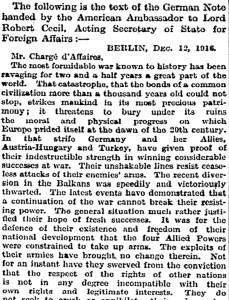

This Section of the story of Swingate centres on the site’s role during in World War One (1914-1918) and covers:

1. Pre-World War I – Swingate and Aviation

2. 1914 – The War will be over by Christmas

3. 1915 – Inventions, Innovations and Developments

4. 1916 – Cannon Fodder, Quagmires and an Offer of Peace

5. 1917 – On the Offensive & the Americans come to Swingate – on Swingate Part IIb – World War I Front Line Aerodrome

6. 1918 – Dover and the End of a War to End All Wars – on Swingate Part IIb – World War I Front Line Aerodrome

1. Pre-World War I – Swingate and Aviation

Bleriot XI aeroplane aviator Louis Blériot. US Library of Congress Wikimedia

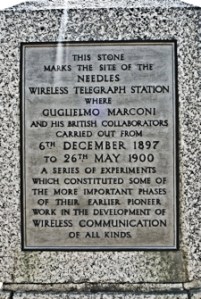

As described in Swingate Part 1 – Marconi, South Foreland and Wireless, Swingate was commandeered by the military in the 1850s and many of Guglielmo Marconi’s (1874-1939) early experiments in wireless communication took place on the site and/or the nearby South Foreland. Historically, it is also significant for on the nearby Northfall Meadow, between Swingate and the Castle on the morning of Sunday 25 July 1909, Louis Blériot (1872-1936) had landed. He had crossed from Sangatte, France to England in his Blériot No XI 25-horsepower monoplane and it was the first heavier than air flight to make the Channel crossing. When he landed, 36minutes 30 seconds after take off, besides making history, he instigated the meteoric rise of interest in aviation in which Swingate played a significant role.

The first aerial crossing of the English Channel had taken place on 7 January 1785 by Dr John Jeffries (1744-1819) and Jean-Pierre Blanchard (1753-1809). In a lighter than air balloon they had made the crossing from Dover. Although not at Dover, in 1804 British amateur engineer, Sir George Cayley (1773-1857) flew a model glider, the world’s earliest known successful heavier-than-air craft. In his paper of 1799, Cayley particularly recognised that the basic principle of heavier-than-air flight is that lift is provided by horizontal surfaces. He went on to say that the other two principles of flight are drag and thrust. Drag is the resistance of the air to a moving body and thrust is the driving force that overcomes drag.

It was in 1853 that Cayley had made his historic adult piloted glider flight and about the same time French engineer, Henri Giffard (1825-1882) was working on the manoeuvrability of airships. In 1852 he flew 27kilometres from Paris to Trappes – north-central France. His machine was a steam engine airship that was more oval in shape than its predecessors – the design made it easier to drive through air. The first fully controlled airship, La France, was powered by electricity and flew in 1884 but it was the invention of the petrol engine that led to more practical airships.

First Zeppelin ascent on July 2, 1900. Library of Congress Wikimedia

German bookseller Friedrich Hermann Wölfert (1850- June 1897) produced a successful airship using a Daimler petrol engine in 1888 and in the following decade, Croatian-Hungarian Dr David Schwarz (1850- January 1897) built the first rigid airship. It was filled with gas contained within a rigid aluminium envelope that was riveted on to a metal framework. The airship, based on this design, was then successfully developed and commercialised by German Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin (1838-1917).

During the 19th century the British Army used balloons and later airships in the First Boer War (1880-1881). Developed by, amongst others, the Royal Engineers, in 1890 they were granted a full Balloon Section with its own Balloon Factory on Farnborough Common, Hampshire. Aviators such as Edwin Alliott Verdon Roe (1877-1958), who later in 1910 founded the Avro Company in Manchester, undertook experiments with the airships there. Also, aviators Samuel Franklin Cody (1867-1913) and John William Dunne (1875-1949) made significant contributions, particularly in engine design. However, the War Office only saw the potential of air flight in reconnaissance and was horrified when, in 1909, Dunne reported that an airship could travel at 40miles an hour! The War Office, having spent £2,500 on the research, immediately cancelled the funding. Of note, by this time Germany had spent £400,000 on aeronautical research!

Orville & Wilbur Wright followed by Horace Short. The Short brothers won the right to build Wright planes. Eveline Larder

On 17 December 1903 near Kitty Hawk, South Carolina in the US, bicycle manufacturers Wilbur (1867-1912) and Orville (1871-1948) Wright, had made the first controlled and sustained powered flights, landing on ground at the same level as the take-off point. By 1905 they had built a flying machine with controls that made it completely manoeuvrable. The US Army showed no interest in the achievement so in 1906, when an American patent was granted to the Wright brothers, they entered agreements with firms in Britain, Germany and France. The first British aeroplane manufacturing company to gain the right to build their aeroplanes was the Short Brothers at Mussell (Muswell) Manor, at Eastchurch on the Isle of Sheppey, north Kent. This was owned and run by Horace Short (1872-1917) and his brother Oswald (1883-1969) and opened in February 1909.

The German government continued to recognise the possibilities of aeronautics and saw the future potential of airships. The British government’s view, on the other hand, can be best stated by Richard Burdon Haldane (1856-1928), the Secretary of State for War (1905-1912). In a letter dated 4 March 1907 he wrote, ‘the War Office has not the least intention of entering any agreement as to flying machines with anyone, or giving the slightest guarantee.’ The French government, however, did see the feasibilities particularly in aeroplanes and encouraged private funding. For instance both Blériot and Anglo-French aviator, Henri Farman (1874-1958) who built a biplane more stable than the Wright aeroplane, were actively encouraged by the French government.

Charles Rolls postcard, commemorating his two way non-stop flight across the Channel Thursday 2 June 1910. Dover Library

In the spring of 1910, wealthy Charles Rolls (1877-1910) saw Swingate Down plateau as having potential for an airfield and persuaded the War Office to rent him the site when it was not required for military purposes. On acquiring the Swingate Aerodrome, as he renamed the area, Rolls had an ‘aeroplane garage’, or hangar as they are now called, erected. On 20 May 1910 a Wright Flyer machine, belonging to Rolls, arrived at Dover and at 18.30hrs on Thursday 2 June he took off from Swingate Aerodrome. Rolls passed over Sangatte, France, at 19.15hrs and after re-crossing the Channel he circled around the Castle in triumph. Rolls landed at Swingate aerodrome at 20.00hrs having made the first two way Channel crossing in an aeroplane. Over 3,000 people witnessed the event, after which Rolls was carried through the town shoulder high. A month later, on 12 July 1910, Charles Rolls lost his life due to a controlling wire breaking that had been added to his Wright Flyer.

The main military purpose of Swingate Downs was for training the volunteers that made up the different brigades of the Territorial Army (TAs). The Royal Engineers, based at the Castle, also used the site to try out equipment, one of which was being overseen by Major John Nassau Chambers Kennedy (1865-1915). This equipment was associated with a wireless station he had set up for military use and was housed in a decommissioned battery in the Castle grounds. As a young Captain, Kennedy had witnessed Marconi’s experiments in wireless communication on Salisbury Plain. He saw the potential of wireless communication for the armed services and subsequently assisted Marconi with many experiments and demonstrations in that sphere (see Swingate Part 1).

In the armed services, flights such as that undertaken by Rolls inspired a number of officers to learn to fly and concurrently, private aircraft producing factories were opening. One such factory was the Bristol Tramways Company owned by George White (1854-1916) – later knighted – together with his brother Samuel (c1862-1928). As a subsidiary, they founded the British and Colonial Aeroplane Company at Filton in Bristol in 1910 to build aircraft using improved existing aeroplane designs. They quickly gained the reputation of being the largest aeroplane manufacturer in Europe! As successful businessmen they also saw the need for flying schools with their own airfields, and opened their first at Brooklands near Weybridge in Surrey followed by a second one at Larkhill, Salisbury Plain, Wiltshire in July 1910.

Maurice Farman Biplane. Flight International March 1910. Wikimedia

On 31 September, two months after the Larkhill airfield opened, aviator and West End actor Robert Loraine (1876-1935) – who first named the aircraft control stick a ‘joystick‘ – was asked to test an upgraded Farman biplane with a special adaptation. The adaptation was a basic Marconi wireless transmitter weighing a mere (for those days) 14lbs. The machine was attached to the passenger seat with monopole antenna wires stretched along the breadth and length of the biplane. The Morse key for tapping out messages was fixed next to the pilot’s left hand and Loraine, who had used terrestrial Marconi transmitters, was asked to send a predetermined message while flying over Stonehenge, on Salisbury Plain, approximately 2 miles away. This he did with his left hand while controlling the aeroplane with his right.

Guglielmo Marconi publicity photograph in front of his early radio apparatus. Smithsonian Institute Libraries Wikimedia

In a hangar at Larkhill surrounding the Marconi receiver was Captain Kennedy and Marconi engineers Harry Melville Dowsett (1879- January 1964), Charles Samuel Franklin (1879- December 1964) and a number of dignitaries. These were headed by the Home Secretary (1910-1911), Winston Churchill (1874-1965); Field Marshal William Gustavus Nicholson, 1st Baron Nicholson, (1845-1918) the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (1908-1912); Field Marshal Frederick Sleigh Roberts, 1st Earl Roberts (1832-1914) and former Commander in Chief (1901-1904); along with Sir John French (1852-1925) later the Chief of the Imperial General Staff (1912-1914) and then Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (1914-1915). Also in the hangar were army and navy officers and one of the army officers was a Major Herbert Musgrave (1876-1918). Loraine did as he was bid and the dignitaries were delighted when the message ‘enemy in sight‘ was received on the apparatus in the hangar. However, the dignitaries generally expressed reservations about the use of aeroplanes for defence purposes.

At the time the Army’s Balloon Section of the Royal Engineers had a couple of airships, five officers who could fly aeroplanes – one of which was Musgrave – and 40 men. Germany had six airships, twenty officers and 465 men. The US government had one airship, one aeroplane, three officers and 10 men but within a year the Aeronautical Division, Signal Corps had been set up and the 1st Aero Squadron had 29 factory-built aircraft. While France had 8 airships, 10 aeroplanes, 24 officers and 432 men. Albeit, within the British armed services a number of officers had taken private flying lessons and Musgrave proposed the formation of an aviation division. This was initially rejected so above the airfield adjacent to the Balloon Factory, they practised manoeuvres using private aircraft. Then on 12 May 1911, at Hendon aerodrome (1908-1968) at Colindale, seven miles north west of Charing Cross, London. Musgrave and his colleagues put on an impressive display. In 1912 the Army Balloon Factory on Farnborough Common was renamed the Royal Aircraft Factory (later renamed the Royal Aircraft Establishment) and employed it’s first aeroplane designer, Geoffrey de Havilland (1882-1965). Musgrave became one of the test pilots.

With the prospect of a possible War against Germany, in November 1911, the Committee of Imperial Defence set up a sub-committee to examine the question of military aviation. They reported on 28 February 1912 and recommended the establishment of a flying corps made up of a military and naval wing with a central flying school and an aircraft factory. The recommendations were accepted and on 26 March 1912 George V (1910-1936) gave his approval to the title ‘Royal Flying Corps’ that received Royal Assent on 13 April. The year before, in 1911, the Army’s Balloon Section of the Royal Engineers had been increased to two companies. Number 1 Balloon Section for balloons and airships and Number 2 for aeroplanes and together they formed the basis of the Military Wing of the Royal Flying Corps founded on 13 May 1912.

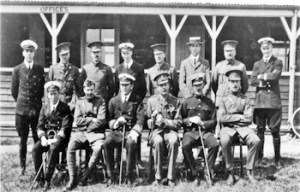

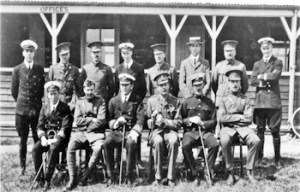

RFC Central Flying School staff in January 1913 at Upavon. The commandant, Capt Godfrey Paine, is 3rd from left on the front row. Major Hugh Trenchard, Assistant Commandant, is immediately to his right. Air Publication 3003. HMSO Wikimedia

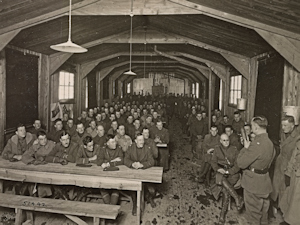

From the outset the Military Wing consisted of three squadrons each commanded by a major but it was not until 1914 the Naval Wing organised itself into squadrons. Nonetheless, the Central Flying School was established at Upavon, Wiltshire and at the time a Major Hugh R Trenchard (1873-1956), was keen to be involved. To do so, he was required to learn to fly but due to his age, Trenchard only had ten days in which to gain his aviator’s licence before he would be 40years of age and too old! Trenchard signed in at Thomas (Tommy) Octave Murdoch Sopwith’s (1888-1989) flying school at Brooklands and successfully gained his wings in time! Trenchard, however, was not a particularly good pilot but his main ability was as an organiser and when he applied that was the skill he hoped to put to good use. He was employed at the Central Flying School but the first Commandant, Sir Godfrey Marshall Paine, (1871-1932) appointed him as an instructor! Luckily for the RFC, Trenchard was shortly after promoted to Assistant Commandant and he ensured that the trainee pilots were well-versed in map reading, signalling and engine mechanics. In December 1912, 32 officers graduated and by that time the Royal Flying Corps had 12 manned balloons and 36 aeroplanes. Their motto, devised by Lieutenant J.S Yule was Per ardua ad astra -Through adversity to the stars.

The establishment of the new Royal Flying Corps (RFC) came in for criticism as flying was seen as a dangerous pastime for rich gentlemen and therefore a waste of public money. This accounted for the reluctance to provide any funding and the disapproval was levelled at Colonel John Edward Bernard Seely, 1st Baron Mottistone (1868-1947) Secretary of State for War (1912-1914). In the House of Commons in May 1912, Seely responded by telling members that the RFC had five aeroplanes that could fly 70 miles per hour and that there were 15 more on order. ‘The Corps also had 26 trained military pilots,’ he added, ‘with another 36 expected to graduate in December by which time the number of aeroplanes would have increased significantly.’ Winston Churchill, at that time was the First Lord of the Admiralty (1911-1915), and expressed his concern about Germany building up her military strength. He went on to say that Germany had five rigid airships, one military, one naval, two civilian and one experimental. He went on to say that opinions differed as which were better, airships or aeroplanes and the subject was still receiving the attention of the Admiralty. Nonetheless, ‘the Navy would continue to endorse the growth of aeronautics as part of the country’s defence.‘ Although Dover’s Member of Parliament, George Wyndham, (1863-1913) agreed with the two Ministers, he made it clear that in his opinion, more money should be spent on increasing the number of aircraft and pilots.

Deperdussin Monocoque exhibited at the Air & Space Museum at Le Bourget, France.

At Larkhill in August 1912, before a military team headed by Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson (1862-1921), a trial of different aircraft took place for the RFC. A total of 30 machines, based on eight different designs, were assessed and each plane had an RFC’s trained military pilot on board. Two of the biplanes were based on the Blériot Experimental or BE series of monoplanes built by the Royal Aircraft Factory – the forerunner of which was the Blériot No XI that Blériot had used to make his historic flight. At the trial, these were flown by Edmond Perreyon (c1882-1913). There were two built by René Hanriot (1867-1925) one of which was flown by Major Sydney Vincent Sippe (1889-1968) and the other by Juan Bielovucic (1889-1949). There was also a Maurice Farman biplane flown by Pierre Verrier and a French Deperdussin Monocoque flown by Maurice Prévost, (1887-1952), a Cody Riplane flown by Sam Cody and finally a Coventry Ordnance aeroplane flown by Tommy Sopwith. The challenge was to assemble the planes and then to carry a load ( a passenger) of 350lb for 3hours, and fuel and oil to last 4hours 30minutes, maintaining an altitude of 4,500feet for one hour the first 1,500feet obtained at 200feet a minute although 300feet a minute was desirable.

The weather was stormy on the day of the test, and the first part – preparation of the aeroplane, showed a huge variation in the length of time taken, from 14minutes 30seconds to 116minutes 55 seconds! Except for the Coventry Ordnance and one of Hanriot’s aeroplanes, the other aeroplanes completed the test successfully. The Hanriot’s number 1 flown by Bielouvucic retired, while the Coventry Ordnance was forced to land after 25minutes. The passenger in the latter was Major Henry Robert Moore Brooke-Popham (1878-1953) – later knighted and the Air Chief Marshal of the Royal Air Force – who reported that a valve spring regulating the petrol supply had broken. Sopwith repaired the faulty valve spring and again set off, managing to fly the furthest distance. Not only were the military and parliament interested in the outcome of the trials but also Prince Edward (1894-1972), the Prince of Wales and the future Edward VIII (1936), who was to actively support the RFC. That year, the estimate for government spending on air defence was £85,000.

The RFC had their first air accident on 5 July 1912 near Stonehenge on Salisbury Plain. Captain Eustace Broke Loraine (1879-1912) and his observer, Staff Sergeant Richard Hubert Victor Wilson (1883-1912) were flying from Larkhill. Both were killed and this had a negative effect on the moral of the other aviators. Later that day an order was issued stating that ‘Flying will continue this evening as usual’, setting a tradition that still holds today. A month later Lieutenant Wilfrid Parke (1889-1912), who had just broken a world endurance record in an Avro G cabin biplane was flying the same plane when he was observed to recover from an accidental spin some 700 feet above ground level at Larkhill. Sadly, on 11 December 1912 Parke was killed when his Handley Page monoplane, in which he was flying from Hendon to Oxford crashed.

Royal Aircraft Factory BE.2 biplane suspended from telegraph wires beside a railway. Imperial War Museum

In September 1912, two experienced aviators, Captain Patrick Hamilton (1882-1912) and Athole Wyness-Stuart (1882-1912), who were undertaking the Central Flying School course and flying a Deperdussin, were killed at Graveley near Hitchin, Hertfordshire. The main witness, Walter Charles Brett (1865-1942) of the George and Dragon public house, Graveley, said that the aeroplane was high up but wobbling about then it appeared to dip down, which was followed by a loud retort, as from a gun, and the aeroplane seemed to collapse altogether and fell to the ground.

Expert opinion was provided by Major Brooke-Popham, who said that the primary cause of the accident was possibly due to a rod working the exhaust in the engine braking. This in turn would have probably broken the vertical strut and the wires that kept the wings in position. Fritz Kollhaven of Deperdussin agreed, adding that the plane would have then been impossible to steer. The following year, in May 1913, ground witnesses described the sound of a loud sharp crack when BE Biplane being flown by experienced Irish pilot, Lieutenant Desmond Arthur (1884–1913) of the Second Squadron, Military Wing, then at about 2,000feet. The weather was favourable for flying but following the loud noise one of the wings collapsed and it plunged to the ground landing besides a railway track.

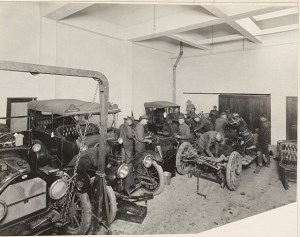

On investigating these and other similar accidents, it was found that lack of maintenance was a principle cause. Indeed, it was cited that because of problems and breakdowns it had taken Lieutenant Arthur 5 days to fly from Farnborough to Montrose, where his accident had happened. In parliament it was agreed that a Maintenance Division of the RFC should be set up immediately. That the Division should be made up of officers, non-commissioned officers and men, all of whom were skilled mechanics and had received full flying instruction and training in the construction of the aircraft and maintenance. The Division was to be divided into sections, each with responsibility for specific aircraft and that each of these units were to be brigaded under the command of a brigade aeroplane officer and each with its own repair shop. This eventually came about and also included ground maintenance crews comprised of mechanics, fitters, metalsmiths and armourers as well as an equipment officer and a transport officer. Each establishment also had a car, five light tenders, seven heavy tenders, two repair lorries, eight motorcycles and eight trailers.

DFW Mars mono and biplanes published in Aeroplane 19, 08.11.1913. The top photograph is the monoplane flown by Lieutenant von Hiddensson at the Strasbourg aeroplane show in May 1913. Wikimedia

In Germany, the interest in aeronautics and the possible usage, both civilian and particularly military continued to grow. This was fuelled by the assumption that the country was vulnerable to invasion on two fronts – France in the west and from the east, Russia. As a defensive measure, in 1905 the German Army Chief of Staff, Alfred von Schlieffen (1833-1913), had drawn up a plan based on at first, taking the offensive against France, quickly beating her and forcing her surrender before Russia had a chance to mobilise her armed forces. To fulfill the Schlieffen plan, as it was called, Germany began building up her military strength including aeronautics.

For this reason the German Military were interested in researching and developing aeroplanes and they held public competitions to assess their versatility. The shows were fully supported by the German Emperor, Kaiser Wilhelm II (1888-1918), who organised the provision of trophies and prize money. Typically, in May 1913, at the Strasbourg aeroplane show, three prizes were awarded. The first was for the best all round performance, the second for the best reconnaissance flight and finally a prize for reliability. On that particular occasion the first prize went to Lieutenant Canter flying a German War Office Rumpler-Taube monoplane. This was the first German military aeroplane to be mass-produced and had a 72 horsepower Daimler engine. Canter’s companion on the flight was Lieutenant Bohmer and he received the prize for the best reconnaissance reports. The third prize, the Prince Albert William Henry of Prussia (1862-1929) Trophy for reliability, was awarded to Lieutenant von Hiddensson flying a Deutsche Flugzeug-Werke (DFW), Mars monoplane. Both the DFW Mars monoplanes and biplanes were consistently found to be reliable and were purchased by both the German military and the British Admiralty.

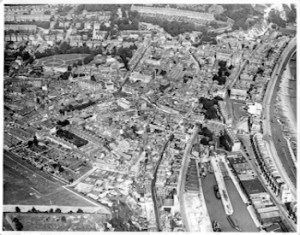

Swingate Downs and the site of the new Dover (St Margaret’s) aerodrome. Looking west towards the Castle on the left is St Mary-in-Castro church and Northfall Meadow. Alan Sencicle

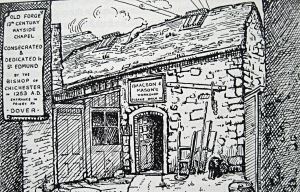

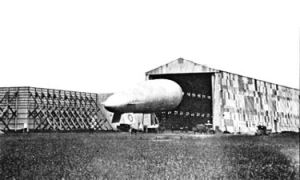

At Swingate, due to the mounting demands of a possible war, the training of ground forces became paramount. Because of the increasing number of military exercises the site ceased to be used as an aerodrome. Then on 14 October 1912, a 450-foot long Zeppelin paid a clandestine visit to north Kent. Shortly afterwards the War Office made £45.000 available to extend the Swingate site and to build a flying depot. The Commander was to be Major Hugh Caswall Tremenheere Dowding (1882-1970) and the new airfield, named Dover (St Margaret’s) aerodrome, was formally established in June 1913 but it was generally known as the Swingate airfield or aerodrome.

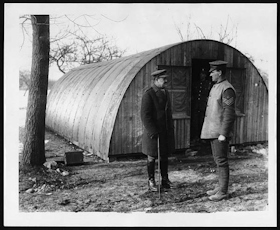

Nissen hut in France c1918. National Library of Scotland Wikimedia

Eventually the aerodrome covered 219acres with three large hangars constructed of brick 180feetx100feet and twelve portable timber and canvas Bessonneau hangars. Besides the hangars, the site had administrative and recreational buildings, workshops, motorised transport garages and a coal yard. During October and November 1913, a portion of No 5 Squadron of the Royal Flying Corps with two Maurice Farman biplanes arrived with the pilots, and ground crew all of whom were billeted in the former Langdon Prison. With the possibility of more men arriving it was decided to accommodate them in Nissen huts – prefabricated steel structures made of arcs of corrugated iron that could be assembled in a few hours. When completed, the aerodrome was categorised as First Class with No 5 Squadron based there.

Mote Bulwark & Guilford battery – 1890

During this time, on Dover’s Seafront, the Admiralty requisitioned Guilford Battery and the surrounding grounds for the Royal Naval Seaplane Patrol. This was part of the Naval wing of the RFC that on 1 July 1914 separated and became the Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS). In 1913 new barracks and administrative buildings were erected at Fort Burgoyne to accommodate the expected influx of men. On Liverpool Street, near the Seafront, new Territorial headquarters, which included a riding school, was completed for use by the Dover Units of the Royal Field Artillery, Royal East Kent Mounted Rifles and the Cinque Ports Royal Engineers.

Swingate Down Map inc Military area. WWI Airfield, Masts, Memorials, Fort Burgoyne, South Foreland & St Margarets LS

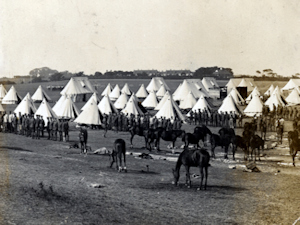

Besides Swingate, other RFC camps were established in the Dover area including at both Dover Castle and Fort Burgoyne, also on Western Heights in the Citadel, South Front and the Grand Shaft Barracks. Prior to redesignation, these camps were classed as Permanent Peace Stations and when the Duke of York’s school was requisitioned by the Depot of the Royal Fusiliers, it too received the same classification along with Langdon Prison, which was renamed Langdon Fort. Additionally, camps were set up at Archcliffe, the Danes on Long Hill, Broad Lees adjacent to Swingate on the Downs, Maxton and at the RNAS Guston Aerodrome on Northfall Meadow. There were also Rest Camps at the Oil Mills on Snargate Street, Victoria Park and at South Front Barracks on Western Heights.

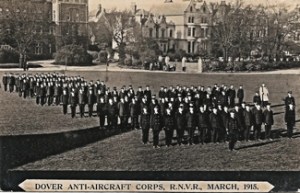

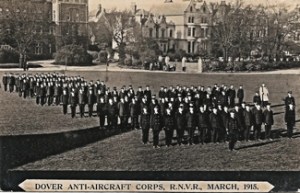

In the last week of July 1914, the Dover Company of the Royal Engineers and the London Electrical Engineers arrived in the town to operate searchlights. The War Office, on 29 July, issued a notice to the RNAS that they were to confine themselves to home defence and the protection of vulnerable points from possible attack by enemy aircraft and airships. The RFC were told that they were to support the Army. On Saturday 1 August in accordance with the Schlieffen plan, Germany declared war on Russia, invaded Luxembourg and crossed the French frontier at several points. The First Lord of the Admiralty, Winston Churchill, issued the order to mobilise all the Royal Navy personnel and the warships still in Dover harbour to establish a war footing. Channel ferries were crossing Dover Strait at speed and out of schedules endeavouring to bring back to England as many people as possible before War commenced. In Dover crowds surrounded the information posts, such as Leney’s brewery office on Castle Street to find out the latest news. They in turn were kept up to date by telephone from the Coastguard at Spioen Kop wireless telegraph station on Western Heights.

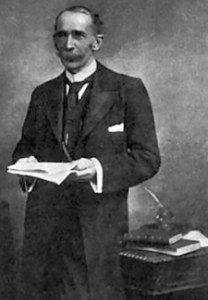

Air Marshal Hugh Dowding c1935 Ministry of Information official photographer

On Sunday 2 August, Russia joined in the conflict on the side of Serbia and France was immediately embroiled. Germany declared war on France and proceeded to march through Belgium, thus violating the Treaty of London of 1839. This recognised and guaranteed the independence and neutrality of Belgium and confirmed the independence of the German-speaking part of Luxembourg. During the evening of the August Bank Holiday Monday, 3 August, some 60 aeroplanes arrived at Swingate aerodrome by which time it was confirmed that Major Dowding, who was head of Fighter Command in World War II (1939-1945) most notably in the Battle of Britain (1940), remained in charge at Swingate. Brigadier-General Henderson had been appointed Commander of the RFC. The Military Wing was commanded by Major Frederick Hugh Sykes (1877-1954), later Air Vice Marshal and knighted. The Naval Wing, or the Royal Naval Air Service as it had been renamed, was under Commander Charles Rumney Samson (1883-1931).

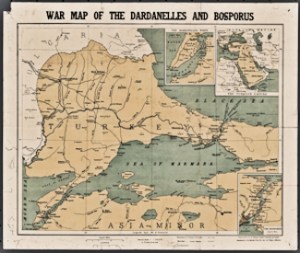

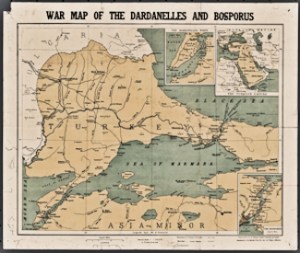

At 23.00hrs on Monday 3 August 1914, the Prime Minister (1908-1916) Herbert Henry Asquith (1852-1928), on behalf of Britain declared War on Germany in accordance with the Treaty of London. What was to begin was expected to be all over by Christmas but in reality it was an intensive and vicious war that was to last until 11 November 1918. Eventually it was fought on four fronts:

– Western Front, considered from the outset to be the decisive Front and Swingate was directly linked.

– Eastern Front, with Russia;

– Italian Front, in the Alps;

– Balkan Front, against the Ottoman Empire – a state that had controlled much of Southeast Europe, Western Asia and North Africa since 1299.

2. 1914 – It will all be over by Christmas

Dover Castle – Headquarters of Fortress Dover during WWI and WWII. AS

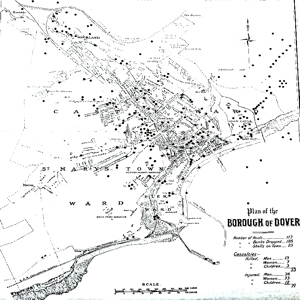

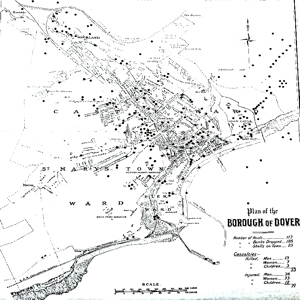

Immediately, in Dover, Mayor Edwin Farley (1864-1939) and the Dover Coast Defence Commander, Brigadier-General Fiennes Henry Crampton (1862-1938), signed notices declaring that the port and town of Dover were to be ‘Fortress Dover’. The headquarters would be at the Castle and Rear Admiral Horace Hood (1870-1916) had been appointed the Commander in Chief. The next day Brigadier-General Crampton was promoted to the General Officer Commanding (G.O.C.) Fortress Dover and notices were distributed that stated mobilisation had been ordered and the Defences of Dover had been placed on a war footing, both on land and at sea. The British Expeditionary Force (BEF), a significant number of Royal Navy ships and all of Britain’s military air fleet were concentrated at Dover.

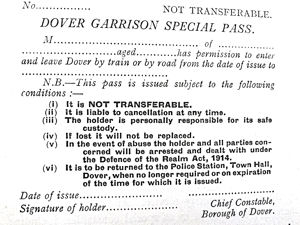

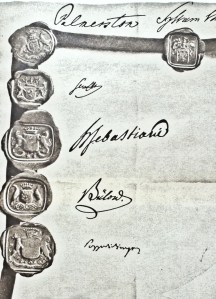

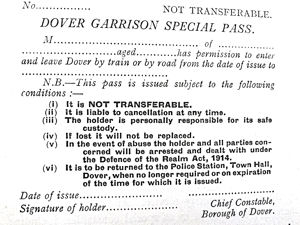

Defence of the Realm Act 1914 World War I Dover Garrison Pass.

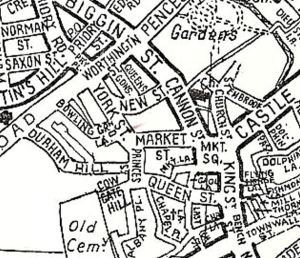

Entrance and exit to the town could only take place by the railways and the main roads to Folkestone (old A20), Deal (A258) and Canterbury (old A2). Each was well guarded and under the Defence of the Realm Act of 1914, a limited number of special ‘Dover Garrison’ passes, were necessary for all those who required to enter or leave the town. This applied to all military and naval personnel as well as the general public. The passes were issued by Dover’s Chief Police Constable, David Fox (1864-1924). The military authorities also had the power to arrest and search anyone approaching the harbour, the Castle, any defensive works and the Seafront. All local newspapers were subject to censorship by the military. On Tuesday 4 August air-raid drills commenced for all civilians and some shelters opened including the vaults of Leney’s Phoenix Brewery in Dolphin Lane. Posted in the window of the company’s offices in Castle Street were notices of all official rulings, news from the Front line and as the War progressed, the casualties who had connections with the town.

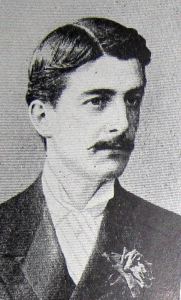

Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) Secretary of State for War 1914-1916. Evelyn Larder

On 23 June Earl Horatio Herbert Kitchener (1850-1916) had arrived in Dover from Egypt and returned home to Broome Park, near Canterbury to celebrate his 64th birthday on 24 June. On the morning of 3 August he was at Dover and about to cross to Calais and return to Egypt, when he was called by telegram to take up the position of Secretary of State for War (1914-1916). The following day, 4 August, Sir John French, from Ripple near Dover, was appointed the Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (1914-1915) that was to go to the Western Front.

Sir John French (1852-1925) Commander-in-Chief of the British Expeditionary Force (1914-1915). Cossira

In an attempt to drive the German Army from the occupied territories on the Western Front, the Allies had agreed to mobilise a coalition force comprising of more than twenty nations. During August, to try and ensure that none would attempt to negotiate a separate peace with the Central Powers (Germany and her allies), on 4 September, Britain, France and Russia signed the Declaration of London. To assist their Allies, Britain had agreed to help meet their financial obligations of goods purchased from the British Empire and the United States. The then Chancellor of the Exchequer (1908-1915), David Lloyd George (1863-1945) was well aware that both the French and the Russian gold reserves were far greater than those held by the Bank of England but it was generally assumed that the War would be over by Christmas. At sea, it was agreed that the Royal Navy would provide the greatest number of ships and on the Western Front, the French and British Armies were to provide most of the soldiers and equipment.

Although France was way ahead of other countries in aeroplane production, including the United States, when War was declared it was evident that the Germans had realised the value of aviation. Their air force was made up of the military Luftstreitkräfte and the naval Marine-Fliegerabteilung, with 232 aeroplanes between them. The aeroplanes were flown by highly trained pilots who were expected to play an active part in the German fighting force. Further, the German senior personnel believed in the potential of both the aeroplanes and the pilots. Thus a team of active aviation researchers, highly trained mechanics and a number of aircraft factories supported their air forces.

By way of contrast, the British RFC and the RNAS had 272 aeroplanes between them but neither the Army or the Admiralty had very little confidence in their potential. Not only were the aeroplanes not considered capable of participating in aerial combat, the pilots were only allowed to carry revolvers or automatic pistols for personal defence! However, officers such as Trenchard, Dowding, Kennedy and Musgrave made their views felt and by the summer of 1914 the British military air fleet consisted of five squadrons, made up of a large number of privately owned aeroplanes – borrowed or belonging to the pilots:

RFC No 1 Squadron – an observation balloon squadron, made up of airships that was shortly after transferred to the RNAS.

RFC Nos. 2,3,4 and 5 aeroplane squadrons primarily used for reconnaissance

At the outbreak of War, RFC Nos. 2,3,4 and 5 were sent to Swingate aerodrome.

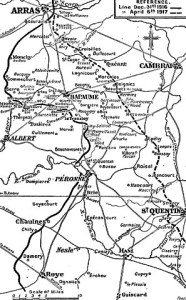

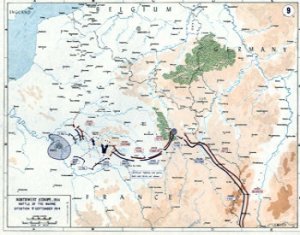

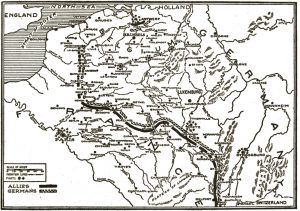

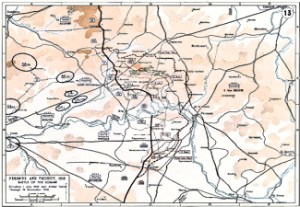

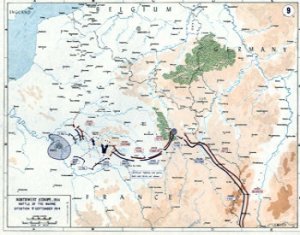

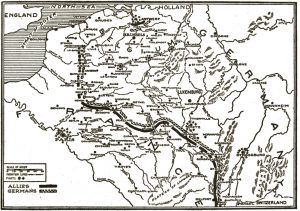

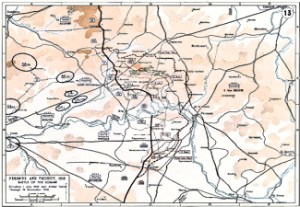

WWI – Belgium, France and Germany showing the situation at the Battle of Marne 5-9 September 1914. Westpoint Military Academy Museum

On 2 August the Germans had demanded the unobstructed passage through Belgium in order to achieve their objective of advancing south to Paris via Verdun-sur-Meuse, and Marne in north-eastern France. The following evening, 3 August, the Belgians took measures to obstruct the German advance at Liège on the Meuse River and on the morning of 4 August, forty-four German divisions invaded Belgium. Their objective was to attack the rear of the French Army massed in the north-east of France, mostly in Lorraine, with the first offensive being the Battle of Mulhouse, south of Lorraine (7-10 August). This was followed by the Battle of Haelen (12 August) in Belgium and although a Belgium victory, the Germans managed to capture Namur, Liège and Antwerp. Between 14 and 25 August the French took a strong offensive stance in the Battle of Lorraine, with the objective of pushing the Germans back. The German priority, on the other hand, was to continue with the Schlieffen plan in order to force France to surrender attacking the French at the Battle of Ardennes, between Namur to the north, Meuse in the east, Marne in the south and Aisne in the west. This took place between 21 and 23 August and at the same time, they engaged France and Belgium at the Battle of Charleroi between 21 and 23 August.

BE 2 (early version) Royal Aircraft Factory two-seat general purpose biplane of the No. 2 Squadron, RFC Montrose. Wikimedia

The BEF under the command of Sir John French had landed in France on 8 August with the remit to stop the German advance on Paris. Three days later Brigadier-General Sir David Henderson, who had been appointed to command the RFC in the field with his second in command Lieutenant-Colonel Frederick H Sykes (1877-1954) from the RFC headquarters, left Farnborough, crossing the Channel by sea, arriving on Thursday 13 August in Amiens, France. That day, 2-5 squadrons in 56 aeroplanes left Swingate also for Amiens, at intervals of about one minute. Not all made it, and from Amiens those that did flew on to Maubeuge, close to the Belgian border, northern France. The first to arrive was a Royal Aircraft Factory BE 2a – a two-bay tractor design biplane flown by Lieutenant Hubert Dunsterville Harvey-Kelly (1891-1917), who had taken off at 06.25hours. An aircraft constructed with a tractor configuration has the engine mounted with the airscrew in front so that the aircraft is ‘pulled’ through the air, as opposed to the pusher configuration, in which the airscrew is behind and propels the aircraft forward.

No. 2 Squadron, led by Major Charles James Burke (1882-1918) from Limerick, Ireland, and No. 3 Squadron led by Flight Commander Lionel Evelyn Oswald Charlton (1879-1958) flew Bleriot monoplanes and Henri Farman biplanes. No. 4 Squadron flew Farmans, B.E.2cs and Avro 504s – a two-bay all-wooden biplane with a square-section fuselage. Major John Maitland Salmond (1881-1968) who eventually became the Chief of the Air Staff (1930-1933) led the squadron. Number 5 (Army Co-operation) Squadron flew BE.2a aeroplanes, some of which had been produced by Vickers the previous year while the British and Colonial Aeroplane Co. made others. The British engineering firm, Vickers, was founded in 1828 and Vickers Ltd (Aviation Department) was formed in 1911. Two of the pilots were Robert Raymond Smith-Barry (1886-1949) and Louis Arbon Strange (1891-1966), both distinguished aviators with Smith-Barry developing flying instruction methods and Strange successfully introducing wartime aeroplane adaptations.

For the duration of the War most of the aeroplanes were supplied to the RFC by 8 private firms who built the aeroplanes to either a government or private approved design. However, the main provider of machines was the Royal Aircraft Factory at Farnborough. The supply of engines was a major problem, eventually eased by experimentation, innovation and replication of foreign produced engines. At the outbreak of War the aero-engine industry in Britain was almost non-existent. There was a lack of experience, skilled labour, suitable engineering works and general wherewithal. As the War progressed expertise increased such that, by the end of the War Britain possessed the largest number and most efficient aircraft engineers in the world – many had learnt their trade at Swingate.

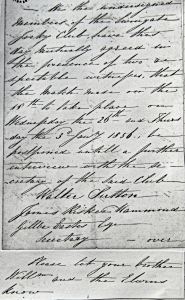

Using flags for visual signalling during WW1. Royal Signals Museum

None of the airmen carried any sort of armaments, as they were not to be involved in combat but one aircraft per squadron was fitted with very crude wireless apparatus in order to transmit directions for artillery fire. This equipment consisted of a large and heavy spark set with its batteries mounted in the plane and a massive crystal receiver on the ground. On the ground, artillery batteries had transmitters consisting of a large, heavy unreliable spark set with cumbersome batteries and a massive crystal receiver. The apparatus used a long wave. The noise of the engine, wind, gunfire etc in the open cockpit drowned out the sound of any Morse Code transmissions sent from the ground. In order to instruct the pilots the direction to be observed, the men in the battery signalled using flags and/or laid strips of white cloth on the ground in prearranged patterns.

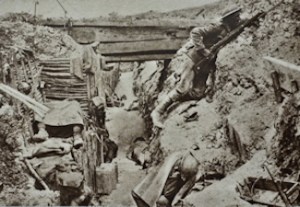

On arrival in France, a total of 63 aeroplanes, 105 officers, 155 men and 320 transport vehicles made up the RFC (British Expeditionary Force) air support contingent. On 22 August the BEF moved up to the Belgium town of Mons with the intention of supporting the French Fifth Army in two lines like a broad arrow with its tip at Mons. However, at the Battle of Charleroi the weight of the German offensive drove the French and Belgians back. From both cavalry and air reconnaissance reports, it was evident that the German forces were rapidly closing in on Mons.

Up to this point, the Germans had employed observation balloons to give them a tactical advantage during the engagements and it became obvious to the British high command that the mapping of enemy positions was of paramount importance if gunners were to be accurate, particularly when firing shells. For the Battle of Mons aircraft reconnaissance transmitted where to aim shells with reference to known features on the issued maps, for instance they would try to tap out, in Morse Code ‘100 yds est of chrch’ and if nearby the pilot would physically point in the appropriate direction. Initially the BEF managed to hold the Germans but the severely weakened French and Belgium armies left the BEF exposed. Although the BEF were eventually forced to abandon their positions it was recognised that the information provided by the pilots of the reconnaissance aircraft did help to avoid a catastrophe. The German superiority however, including the use of aeroplanes in combat, overcame the Allies resistance at the Battles of Le Cateau (25 August), Noyon (26 August) and St. Quentin (29–30 August).

On 3 September French reconnaissance aircraft pilots spotted General Alexander Heinrich Rudolph von Kluck’s (1846-1934) German 1 Army change direction. This contradicted intercepted radio messages between the German high commanders that stated instead of going south-west to Paris, the German Armies were to turn east in order to trap the Allies between Verdun-sur-Meuse and Paris. Field Marshal Karl Wilhelm Paul von Bülow (1846-1921) German 2 Army was to be the striking force while General von Kluck’s (1846-1934)’s Army was to protect the flank and the Allies were taking action accordingly.

WWI Front Line following the Battle of Marne September 1914. Solid lines show Allies trench fronts, dotted the German. The Race to the Sea. Wikimedia

So far in the offensive, von Kluck’s Army had been the striking force and at that time, in keeping with the pre-war tradition of German field commanders’ independence, he was free to take decisive action contrary to that of the high command if needs necessitated. Von Kluck was aware that more British reinforcements had landed in France but was unaware as to how many and their combat capabilities. As his Army was moving east, he reasoned that potentially the British could be a danger to his tiring army, so he took independent decisive action and turned south-west towards Paris rather than going east towards Verdun. The Allies changed their action plan.

Battle of the Marne 5-12 September 1914. A shell has exploded on the road side while ammunition going to the Front is passing. Tom Robinson collection

A counter-attack was launched by the French and the BEF along the Marne River that became known as the First Battle of Marne (5-12 September). This forced the German Army to retreat northwest to a defensive line along the Aisne River and resulted in the First Battle of Aisne (13-28 September). On 15 September an RFC reconnaissance pilot flying over the German lines took the first British Army aerial photograph of the conflict. In January 1915, the Experimental Photographic Section of the Royal Flying Corps was formed under the command of Lieutenant John Theodore Cuthbert Moore-Brabazon, later 1st Baron Brabazon of Tara (1884-1964). It consisted of two officers and three other ranks.

The Battle of Aisne was followed by what became known as The Race to the Sea as the Germans aimed for the Channel and the Allies fought to stop them. After a series of disorganised battles in which both sides suffered huge losses the Germans final attempt at a breakthrough was near the Belgium city of Ypres in late October 1914. The British Army, under the command of Sir John French remained at Ypres. To stem the advancing Germans and save the Channel Ports and Paris the First Battle of Flanders (19 October – 22 November 1914) and the 1st Battle of Ypres ensued (19 October-30 November). Lying on a forward spur of the low ridge that covers the town of Ypres, is the village of Gheluvelt and this was the last point retained in British hands from which the German line could be dominated. By noon on 31 October, the Queens, the Royal Scots Fusiliers, the Welsh and the Kings Royal Rifles regiments had been overwhelmed, while on the right the South Wales Borderers had been forced to retreat. This tantamount to the effective loss of Gheluvelt creating a serious gap in the British line through which the Germans could break through.

WWI German machine guns and trench mortars captured at Gheluvelt 31 October 1914 in front of a German pill-box. Wikimedia

That afternoon the Second Battalion of the Worcestershire Regiment in Polygon Wood – afterwards known as Black Watch Corner – and under the command of Major Edward Barnard Hankey (1875-1959) and guided by Captain Augustus Francis Andrew Nicol Thorne (1885-1970) later became a General and was knighted, of the Grenadier Guards, attacked. It was raining heavily and they were in full view of German guns. Out of 370 men, 187 were killed or wounded. They saved Gheluvelt and the foothold between Ypres and the French border. Of note, for the saving of Ypres, Sir John French was made the Earl of Ypres and when he was buried in the churchyard of St. Mary the Virgin, Ripple on 27 May 1925 the Second Battalion of the Worcester Regiment formed the funeral party.

While this was taking place the Belgium Army was involved in the Battle of the Yser (16-30 October) along a 20 mile stretch of the River Yser and Yperlee Canal between Nieupoort and Diksmuide in north-west Belgium. By this time the much reduced small Belgium Army was exhausted and the Germans were expecting to take over the country giving them direct access to the sea. However, even though the Belgians backs were against the proverbial wall they managed to stop the German advance by flooding a large expanse of the country. This was from the Belgium North Sea coast between Nieupoort and Westende to Diksmuide, which was occupied by the Germans. Thus they had blocked the German reaching the sea and invading Britain. Further, to the south, the German Army had successfully been split with a militarised zone of the German Front along the Belgium border with France that was totally separate from the rest of German occupied France.

Map of the area of the Battle of the Yser. Belgium. Armée Volume 1 Subject World War, 1914-1918

Because of the outcome of battles that had been fought on Belgium territory since the outbreak of War, King Albert I of Belgium (1909-1934) was sceptical of offensive warfare. It had thus far proved costly and he felt that it was unlikely that decisive victory could be achieved by the Allies. This being so, the best that could be hoped for, he reasoned, was a mediated peace and Belgium’s best interests would be served by neutrality until such time that Germany would be forced to open negotiations. As for Britain and France and their Dependencies, they continued to fight and took up positions in a continuous line of trenches, barbed wire entanglements, blockhouses and underground shelters.

Throughout all of these campaigns the RFC sustained heavy losses undertaking reconnaissance yet the airmen asked for authority to participate in combat! Taking little notice of reports that were coming from the Front that both the German and French, like the British aviators, were proving the capabilities of aeroplanes – something that was echoed by the troops on the ground, it was left to the media to make these views felt. The Times (14.09.1914 page 6) reported a conversation with a private in the Royal West Kent Regiment, who told of an air-battle between a German and a French aircraft. He said, ‘the Frenchman manoeuvred to get the upper position of the German and after about ten minutes or so the Frenchman got on top and blazed away with his revolver. He injured the German so much that he was forced to descend and when found he was quite dead.’

Etrich Taube II monoplane the first military aeroplane in the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy Army 1914. Takkk Wikimedia

Nonetheless the British pilots were still refused to be allowed to participate in combat. But at Noyon, northern France, on 26 August 1914, Harvey-Kelly virtually tail-gated a German Taube II aeroplane while flying his BE 2a. As he was not allowed to use armaments, Harvey-Kelly used aggressive flying tactics and forced the German pilot to land. When later the British military attitudes towards the role of airmen changed, it was officially acknowledged that Harvey-Kelly was the first British pilot to bring down a German aeroplane! The Taube was originally designed by Igo Etrich (1879-1967) and was known for its unique wing form, which was copied from the seeds of the Peruvian cucumber (Alsomitra macrocarpa) and both the seeds and the plane were renowned for being able to fly long distances.

Back in Britain as part of the Fortress Dover defences, a series of trenches and redoubts were constructed on Swingate Downs. From aerial photographs held by the Imperial War Museum taken later in the War, it appears that there were three redoubts built at Swingate. Also, adjacent to the accommodation provided for the RNAS at Guston Aerodrome, more RFC accommodation huts were erected and the nearby Connaught Barracks had been built. Between Fort Burgoyne and the Duke of York’s school, tin huts (later called Tin Town) were erected as accommodation for the RNAS, whose role at this time was to provide reconnaissance reports for the defence of the Admiralty Harbour.

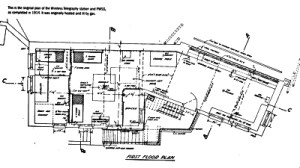

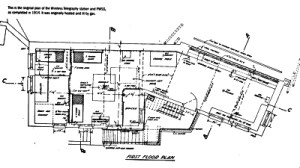

Plan of the original WWI Castle Wireless Telegraph Station. English Heritage poster

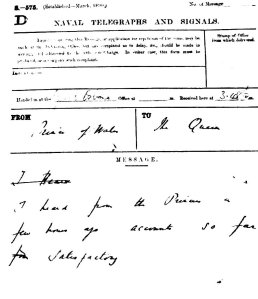

At the Castle, the military wireless station in a decommissioned battery set up by Major Kennedy was renamed the Port War Signalling Station and kitted out. Kennedy had adapted the original gun battery magazines to house a generator and electrical batteries to provide power for the wireless. He had also erected a tall aerial, close to the Castle wall which was stabilised by a series of large blocks spaced equidistant for the rings which held the stays connected to the mast. The station communicated with Admiralty House on Marine Parade, Royal Navy ships, the Admiralty signal station on Admiralty Pier and the Admiralty Spioen Kop signal station in the Citadel on Western Heights.

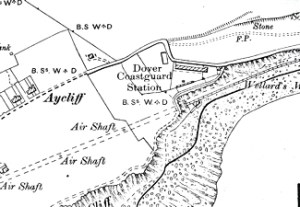

Typical Coastguard Concrete watchtower c1900-1960s. Alan Sencicle Collection

The Coastguard at this time came under the auspices of the Admiralty and in 1903 the office of Admiral Commanding Coastguard and Reserves had been established. Admiral Sir Arthur Murray Farquhar 1855-1937) was appointed and held the post until June 1915. The main Dover Coastguard Station, or to give its correct name Townsend Coastguard station, was at Aycliffe. Its antenna was on Shakespeare Cliff and the Coastguard was also in communication with Portland and Sheerness as well as both the local navy and military signal stations. On the east side of the Castle close to Swingate Down were Coastguard cottages not far from a typical coastguard watchtower on the top of cliffs close to the site of the present day coastguard station. Up to 1898, the watchtower was approached by a zigzag path, on Corn Hill at the eastern end of Langdon Hole but was demolished that year to make way for the Langdon Battery.

A second coastguard signal station occupied the top floor of the Clock Tower on the Seafront and that one was in contact with the Townsend Station and the Harbour signal station which occupied the same premises on Admiralty Pier as the Royal Navy signal station. Prior to World War I there were about 22 coastguard stations along the coast of East Kent between Margate and Hythe. Many were equipped with wireless signalling equipment, as the watchtower on Swingate Down was, as the War progressed. Retired naval and military personnel along with sea captains on two-year secondment awaiting ships, mainly staffed these stations and since 1857, the Coastguard had been formally embodied for ‘the Defence of the Coasts of the Realm, and the more ready manning of the Navy.’ This did not include rendering assistance to vessels in distress and saving the lives of persons on board.

In November 1914, the term Military Wing of the RFC was abolished and replaced by Administrative Wing but the favoured term for military aviators was just RFC. By that time there were six squadrons in France, divided into 2 ‘Wings’ of 3 squadrons each. The Wings were commanded by lieutenant-colonels. However, the role of pilots remained that of reconnaissance but a British squadron from Swingate and Dunkirk successfully bombarded the Belgium port of Zeebrugge on 23 November. An experimental branch of the Military Wing of the RFC had been formed back in March 1913 under Musgrave that included research in ballooning, kiting, photography, meteorology, bomb-dropping and wireless telegraphy. The latter, in which Major Kennedy was involved together with Captain Baron Trevenen James (1889-1915), led to the creation of the Headquarters Wireless Telegraphy Unit (HQ WTU) on 27 September 1914.

A crew member of a British SS ‘Z’ Class airship about to throw a bomb from rear cockpit of the gondola. Wikimedia Commons

The growing pressure on communication, particularly by wireless, was beginning to be recognised and on 8 December 1914 at St. Omer, France the No. 9 (Wireless) Squadron, under the command of Musgrave and including Captain James, was part of the newly formed Bomber Squadron of the RFC. The bombs, at that time, were basically aerodynamically shaped hand grenades, weighing between 1 and 2 pounds with a percussion fuze in the nose that detonated on impact with a hard surface. They were carried in the cockpit of the plane or gondola, in the case of airships, and dropped by hand over the side. No. 9 (Wireless) Squadron was made up of two flights and they were tasked with developing the use of radio for reconnaissance missions through artillery spotting on which bombs could be dropped.

In command of the 1st Wing of the Indian Corps was Major Trenchard, and although he could see what Musgrave was trying to achieve, as his commission was such that he had no influence with the senior military personnel. They were not impressed and the project was officially abandoned on 22 March 1915. However, the use of the wireless failed to impress the senior military personnel and was officially abandoned on 22 March 1915. The preference was for the Telegraph Troop, that had been formed before the War, to install telephone equipment and as a mounted unit to carry messages. The Troop also had dogs trained to carry messages between trenches and homing pigeons trained to carry messages back to the established Headquarters from the front line. Albeit, in England, an increasing number of amateur wireless operators that were impressed by the apparatus were also being arrested and heavily fined for having it without the consent of the Post Office.

On the Western Front, Field Marshal French and Marshal Joseph Jacques Césaire Joffre (1852-1931) were both of the opinion that only a war of attrition – wearing the Germans down over a prolonged period of conflict – would bring about their capitulation. Albeit, even jointly, both the British and French armies knew that they were against a formidable enemy. As the winter of 1914 set in, it was agreed that the British would launch an offensive to push the Germans further north. Field Marshal French planned to achieve this by making six simultaneous small-scale attacks in the Givenchy area of north west France, by men of the Indian Corps. These men had shown their mettle at Ypres where they had suffered heavy losses but carried on nonetheless.

Formation sign of the First Indian Corps in the First World War. Wikimedia

Field Marshal Roberts, although retired, took a keen interest in the Indian troops that had arrived on the Western Front. He quickly made it known that they were inadequately attired for the cold European winter. It was also evident to Roberts, that their religious beliefs were not being taken account of with regards to the contents of their food rations and had made a formal complaint to the High Command. These and other oversights he was personally dealing with through Trenchard, then on 14 November, Roberts died of pneumonia at St Omer, while visiting the Indian Corps. His body was taken to Ascot, Berkshire, by special train for a family funeral service on 18 November before being taken to London for a lying-in-state in Westminster Hall. Field Marshal Roberts was given a state funeral with representatives of the Indian Corps, including Trenchard, in attendance followed by burial in St. Paul’s Cathedral.

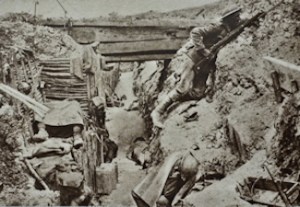

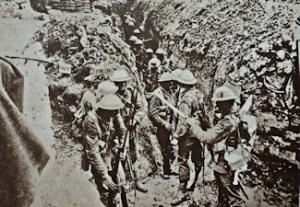

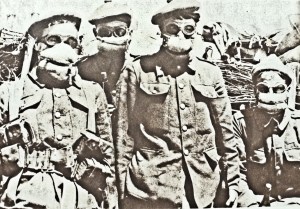

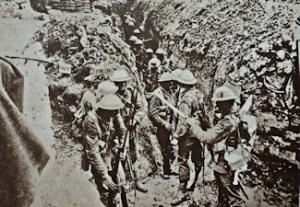

Warmer clothes eventually arrived for the Indian Corps, but footwear was totally inadequate for the quagmires of the trenches. Further, stocks of ammunitions were in short supply and so only forty rounds were issued with each gun and a limited number of hand grenades. In the early hours of Saturday 19 December the temperature was below freezing and it was very wet when the Indian Corps attacked, in what became known as the Battle of Givenchy (18-22 December). Although they came under heavy German machine gun fire the Corps were initially successful, taking two German lines.

The enemy then quickly regrouped and with the backing of aeroplanes, counter attacked. The minefields, the Indian Corps had traversed, together with gunfire and bombs the Germans dropped from their aeroplanes soon caused a significant number of injuries and deaths. Then the German infantry moved in and over 800 hundred men of the Corps were taken prisoners of war. Before the Battle started, many were already suffering from debilitating frostbite and trench foot – a painful circulatory disease caused by standing in cold water for long periods of time that resulted in blisters, open sores, fungal infections and eventually gangrene. Of the 800, many died before even reaching the prisoner of war camp. Shortly after Trenchard was promoted to Command the RFC in the Field (France) but the whole of the Indian episode was to have a major impact that was to influence his decision making as he continued to rise through the ranks.

Alfred Leete WWI recruitment poster – Kitchener pointing and the caption ‘Britons Wants You’. Eybl, Plakatmuseum Wien. Wikimedia

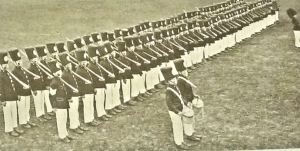

Due to the heavy losses but to avoid the need to introduce conscription, Kitchener launched a campaign designed by graphic artist, Alfred Leete (1882–1933) featuring a picture of Kitchener pointing at the reader with the caption ‘The Country Wants You.’ The campaign was successful with over one million men enlisting by January 1915. Nicknamed ‘Kitchener’s Army’ in December 1914, four battalions were formed in Dover: the 9th Buffs, the 10th East Surrey Regiment, and the 14th and 15th Battalions of the Royal Fusiliers. These battalions were attached to Western Heights, Fort Burgoyne and Swingate but were billeted with the civilian population. They remained in Dover for several months, mainly undertaking drafting administration and organising training, clothing, transport etc for other volunteers that were destined to be sent to join the Expeditionary Forces on the Continent. The defence of Kent was in the hands of the Kent Defence Corps – a fully equipped force of both the naval and military services with headquarters in Canterbury. Because of the influx of new recruits, the British Expeditionary Force, under the overall command of Sir John French, was split into two on 26 December 1914. The First Army was under Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Haig (1861-1928) and the Second Army under General Sir Horace Lockwood Smith-Dorrien (1858-1930).

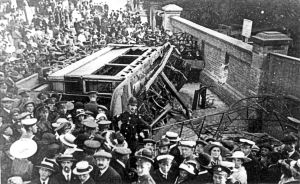

WWI – London Buses taking fresh troops from Calais to the Front Line 1914. Eveline Larder

At their own request and where possible, new recruits were kept within the communities they had come from. On completion of training they were shipped from England as reinforcements, mainly via Dover – Calais, on commandeered cross-Channel ferries. These had been commandeered as transport ships at the beginning of the War and many were also used as hospital ships for the return journey. The recruits were then taken to the Front Line on buses. Using the same vehicles and ships, the injured members of the Indian Corps had been taken back to Calais then on to Dover. During December 1914, some 4,000 men were killed on the Western Front and many more were injured. Because of the atrocious conditions that the Indian Corps had faced prior to the Battle of Givenchy and the inadequacy of their armaments during the Battle, the British General Staff feared possible mutiny. It was suggested and agreed that the remaining members should be withdrawn from the Front Line over the following months but due to shortage of men, this did not happen. Instead, they did receive adequate clothing, footwear and appropriate food.

Dover Society Plaque marking the First Aerial Bomb to fall on Great Britain, landing in Taswell Street on 24 December 1914. A Sencicle

At 11.00hrs on Wednesday 24 December 1914 the first German aerial bombing raid on the United Kingdom took place. Lieutenant Alfred von Prondzynski flying a Taube II aircraft dropped a bomb aimed at Dover Castle. The bomb landed in a cabbage patch near Taswell Street. The blast broke an adjoining window and threw the St James Rectory gardener, James Banks, out of a tree but he was only slightly hurt. Nearby, there is a Dover Society plaque marking the event.

Two aeroplanes from Swingate and a seaplane from Mote Bulwark chased Prondzynski’s aircraft, the pilots of which were only armed with pistols that they were only allowed to use in self-defence. Lt. Von Prondzynski managed to evade them and when he returned to Germany he was given a hero’s welcome. In Dover fragments of the bomb were mounted on a shield and presented to George V. Another fragment was bought at auction for £20, by a man from Bootle on Merseyside and the money given to the Red Cross. The raid was one of the rare occurrences of an aeroplane attack on Britain in the early part of the War, the Germans preferring the less flimsy airships that could carry much larger bombs than the hand thrown bombs carried on aeroplanes.

The Germans had four types of airships, the Zeppelin, the Shütte-Lanz, the Parseval and the ‘M’ type military airship. The Zeppelin was recognised by its long stretched tubiform shape envelope with one, the L 33, brought down in Essex. It was described as 680feet long weighed 50 tons, had four gondolas, a total of 6 x 240 horsepower Mercédès engines and five propellers. It was estimated that she carried 2,000gallons of petrol and the envelope was filled with 2million cubic feet of gas. The L 33 was fitted with 60 bomb-droppers, had three control wheels in the captain’s cabin and a crew of 22 officers and men. It took about a year to build her and cost between £250,000 and £500,000.

WWI German Schütte-Lanz Airship SL2 bombing Warsaw, Poland 1914. Hans Schulze. Library of Congress

The Shütte-Lanz had a smaller fish-form body and carried behind them horizontal and vertical steering surfaces. They had five gondolas, three under the keel and the other two were higher, right and left of the keel. The Parseval had a cigar-form body and was more compact, carrying only one gondola from which a thick tube led to the airship body. The steering planes were four sided and the colour of the skin was yellow. Finally, the Military airships were a torpedo shape with the keel running the full length of the underside. The conning tower was at the front end of the keel with the two engine cabins further aft. The keel was built into the gas envelope to form one body and the hull was again yellow.

In the trenches, the distance between those of the Allies and those of the Germans was not far, indeed, they could hear the sound of each other’s voices and smell cooking. Both sides, by Christmas 1914, had suffered severe losses and the trenches were cold, wet and muddy. If a soldier put his head above the parapet, it was sure to be shot at and comrades lay dead in no-mans land between the two lines of opposing trenches. The senior officers, concerned that the men would become morose and lethargic, which would affect future offensives, made sure that they were kept busy and at the same time instilled harsh discipline. On the evening of 24 December, some German soldiers stationed near Neuve Chapelle erected Christmas trees, complete with candles and paper lanterns on the parapets of their trenches and started singing well known carols.

Stationed on the other side of no man’s land was the British 18th Brigade under the command of Brigadier-General Walter Norris Congreve (1862-1927) from Chatham, Kent. Of what happened that day, Congreve recounted in his report, saying that one of his men climbed over the parapet of his trench, into ‘no man’s land’ and joined in the singing of a carol. ‘Other men then joined him from his platoon and soon what seemed like a choir of men, both British and German, were singing carols.’ He went on to say that officers and men, from both sides, exchanged cigars and cigarettes. The Brigadier-General added that he was reluctant to personally witness the scene of the truce for fear he would be a prime target for German snipers! By Christmas Day, the Front Line truces had spread and this also enabled the men from both sides to remove from no man’s land their dead comrades and bury them.

3. 1915 – Inventions, Innovations and Developments

By New Year 1915, thought-through contingency plans were being put into operation and the British high command were beginning to realise that aeroplanes were a valuable asset. The Central Flying School at Upavon, Wiltshire had increased its intake to 40 students a time but there was an acute shortage of experienced pilot instructors as most had been sent overseas. Experienced pilots were brought back for R&R (rest and recuperation), during which time they trained new officers to fly. There were also only 4 government aerodromes – one of which was Swingate – so civilian aerodromes were pressed into service.

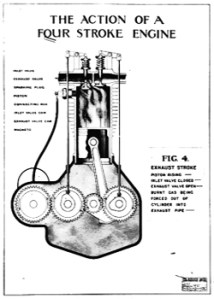

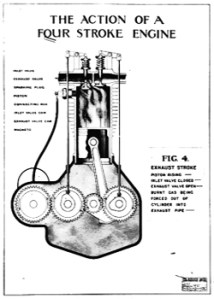

WWI Training slide – The Action of a Four Stroke Engine. From the Robert McKenzie fonds. Wikimedia

Other changes were afoot when an Army order, dated 16 January 1915, was issued abolishing the post of Officer commanding the RFC. It was specified that the ‘Wings,’ which had been created the previous November, were to consist of between two and four squadrons under a Wing Commander. Further, one flight in each squadron was to specialise in bombing as well as normal duties. An additional Wing Commander was also appointed to command the RFC depots, one of which was Swingate, and he was in charge of records, reserve aeroplane squadrons and additional training. Civilian voluntary recruits, without flying experience on enlistment were also sent to an RFC depot for training. Their training started by learning the ordinary duties of a soldier and then as air mechanics for the technical section of the RFC. The training was expected to take six months, followed by specialist training at an aerodrome that would be his base. Some out of the ranks were given the opportunity to train as pilots, observers or photographers as well as mechanics and all who trained at Swingate undertook a course in aerial gunnery at Lydd and on the practise range at Hythe. By May 1915 there were eleven government aerodromes and 235 officers were actually under instruction as pilots. Amongst the trainees were volunteers from Canada and South Africa who successfully completed training. By the end of 1915 approximately 800 Canadians and possibly twice the number of South Africans were RFC pilots, observers or ground crew. On gaining their wings, all the pilots and observers plus graduating ground crew were given 48 hours leave before being posted to the Front.

Meanwhile, enemy U-boats (submarines) were the scourge of Channel shipping. The first German U-boat appeared in the Channel around the middle of September 1914, sinking the Aboukir, Hogue and Cressy off Zeebrugge. Immediately after, the Admiralty gave notice that a minefield was to be laid in the eastern entrance to the English Channel, between the East Goodwin Lightship and Ostend. The Scout boat, Attentive, was attacked by a U-boat/submarine on 27 September, which led to the withdrawal of the Scouts from patrol duties. They were replaced by the Dover Patrol as part of Fortress Dover that was under the command of Vice Admiral Hood. The Dover Patrol consisted of naval destroyers, small submarines, drifters, requisitioned fishing vessels and the Royal Naval Seaplane Patrol based on Marine Parade. The Patrol’s main function was to stop U-boats passing down the Channel.

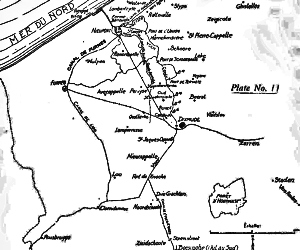

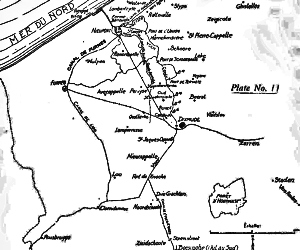

Map of Belgium. Wikimedia

On 21 January 1915, German U-boats moved into newly erected submarine bases along the Channel, North Sea and into the Baltic. The main German base for the Channel was at Bruges, the capital of West Flanders in northwest Belgium. The city had outlets at Zeebrugge nearby on the North Sea coast of Belgium and further south at Ostend. Germany saw the behaviour of British sea defenders, such as the Grand Fleet, based in the Orkneys at Scapa Flow, and the Dover Patrol, as a blockade against their much-needed resources from America. This was confirmed in their minds on 11 February when RFC pilots based at Swingate and under the command of Wing Commander Samson of the RNAS, were ordered to attack these submarine bases. A squadron of 34 aeroplanes attacked the bases at Bruges and Ostend by the pilots dropping bombs over the side of their cockpits. On 16 February, 48 British aeroplanes bombarded Ostend, Middelkerke, Ghuistelles and Zeebrugge in Belgium. On 18 February 1915 Germany retaliated by launching their blockade of Great Britain, declaring that, ‘All the waters surrounding Great Britain and Ireland including the English Channel, are hereby declared to be a war zone. From 18 February onwards every enemy merchant vessel found within the war zone will be destroyed without warning to the crew and passengers.’

Royal Aircraft Factory BE 2 aeroplane. Tony Hisgett, Birmingham, UK. Wikimedia

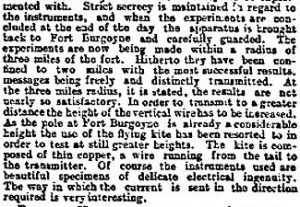

During this time Swingate had become a major training establishment of pilots for the RFC and trainees with their tutors piloted the aeroplanes. The men and officers commandeered as tutors at Swingate all had practical experience in their various fields on the Western Front and initially they were none too happy about their new posts. Indeed, they quickly made it known that they had signed up to fight. Then Major Trenchard visited Swingate, was persuasive and before he left the tutors saw their new role in a positive light. He later noted that pilot tutors had said that if they were going to be allowed to participate in combat, they would prefer single seater planes to two-seaters, as they were more easily manoeuvrable. Two-seaters aeroplanes, they had said, were cumbersome. Further, the Swingate training aeroplanes were mainly BE.2a’s from the Western Front, damaged but sufficiently airworthy to be flown back to Swingate for repairs. These were carried out by the trainee mechanics on the base under the supervision of experienced tutors and it was also noted that the pilot tutors had asked to have armaments that could be used in combat.

Vickers pusher F.B.5 aeroplane, nicknamed the Gunbus. World’s first operational fighter aircraft. Wikimedia

At the time the Lewis machine gun was being used but due to its open bolt firing cycle it was almost impossible to synchronise. Some RNAS aircraft, notably the Bristol Scouts, had an unsynchronised fuselage-mounted Lewis gun positioned to fire directly through the propeller disk, but were not often not synchronised hence the possible reluctance of senior RNAS personnel for pilots to take part in aerial combat. Prior to the War, Vickers designer Archibald (Archie) Reith Low (1878-1969) had been experimenting with machine gun carrying aircraft. The prototype was eventually developed as the pusher type F.B.5 (Fighting Biplane 5), a two-seater rear engined plane that avoided the problem of firing through the two-bladed propeller as it was behind the pilot, facing backward, rather than at the front of the aircraft.

The F.B.5 was armed with a single drum-fed .303 inch Lewis gun mounted at the front cockpit, operated by the observer who could fire it directly forward without an obstructing propeller as well as being reloaded or cleared in flight. Specifically built for air-to-air combat, the tutors at Swingate were impressed, however they did report that due to the pusher design, the single 100 hp Gnome Monosoupape nine-cylinder rotary engine was not as efficient as in tractor designed craft. This was due to the tractor types having the airscrew in front pulling the aircraft through the air, whereas the pusher type resulted in more drag due to the struts and rigging necessary to carry the tail unit. The F.B.5, nicknamed the Gunbus, came off line in February 1915 becoming the world’s first operational fighter aircraft when in July 1915, No 11 Squadron, some leaving from Swingate, arrived in France fully equipped with these new combat planes.

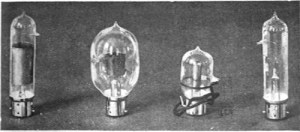

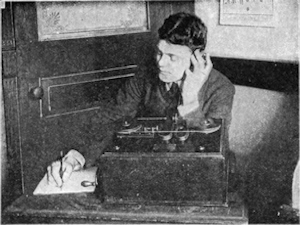

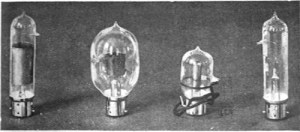

RFC British wireless transmitter c1915 – MWT marconiheritage.org

The first major attack launched by the BEF on the Western Front in 1915, was on 10 March at the Battle of Neuve-Chapelle (10-13 March 1915). In the previous months a considerable number of fresh troops, crewed aircraft supported by mechanics with equipment plus special units of photographers with cameras designed for purpose had arrived. By this time the Marconi Wireless Telegraph Company had also developed their aircraft transmitter and Musgrave’s team devised ways of fitting it into the confined space of the aircraft’s cockpit. The small, compact equipment had a range of 10 to 12 miles and required about 40watts. As it was deemed almost impossible for the pilot to transmit and fly the plane at the same time, the transmitter was designated to be used in two seater aircraft by the observer. To ensure that the transmitting equipment was close at hand, the Morse key was strapped to the top of the observer’s leg between his hip and knee. The battery was on the floor between his feet. Even though the equipment was small, the wireless made it very difficult for the observer to change position, something he had to do if he was to maintain his observations.

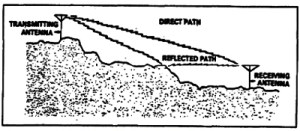

Making the ground personnel aware that a message was being sent was usually done by the blasting of a Klaxon horn but the actual transmission of messages was fraught with difficulties. It was almost impossible to continue tuning while rapidly changing distances and altitudes. The actual transmission of messages was also fraught with difficulties particularly tuning in due to the rapidly changing distances and altitudes. The aerial wire was about 250feet long and was unwound by hand from a spool on the fuselage next to the observers’ position. This had to be done with great care, as the wire was deadly if it came loose and wrapped itself around the aeroplane’s control systems. Research had shown that it was possible to use much shorter aerial wire with the metal aeroplanes but most of the aeroplanes on the Front were wooden. There were two more problems, the first was making it clear to the ground personnel where exactly the targets were and second the receiving of messages owing to the noise of the engine.

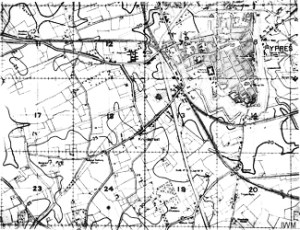

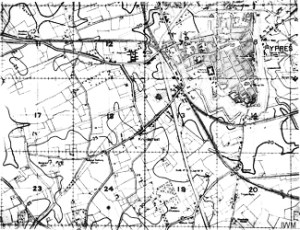

Musgrave & James style map of Ypres. British Army the Western Front, 1915-1918. Imperial War Museum

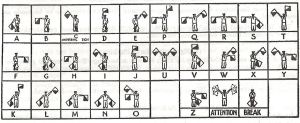

Musgrave was informed that he was to be transferred to take command of the 104th Royal Field Artillery Battery, but prior to leaving he devised a system with Captain James. He had devised a system using wireless telegraphy to help the artillery hit specific targets based on compass readings and the estimated distance from key locations shown on both the observer’s and the ground artillery commander’s identical maps. With James flying an aeroplane and Musgrave on the ground, they developed and simplified James innovation to enable the observation to be rapidly repeated. Using two identical maps, they divided the area under observation into Zones and each Zone was divided into squares with A, B, C etc. on the horizontal axis going from left to right and 1,2, 3 etc. on the vertical axis going from top to bottom. The observer after identifying the position of an enemy target on his map repeatedly transmitted in Morse Code messages such as A3 etc. to the artillery commander. This was inaugurated at the Battle of Neuve-Chapelle and this innovation quickly spread throughout the Allies lines.

Following Musgrave’s transfer, No. 9 (Wireless) Squadron was broken up but on 1 April the former researcher at the Marconi experimental establishment, Brooklands, Captain Charles E Prince, then serving with the Westmorland Cumberland Yeomanry, was sent to his old establishment. By this time it had been commandeered to become the RFC Wireless Training School and Trenchard told Prince that his remit was to develop ‘a system of air-to-air and air-to-ground radio telephony. A one-mile all-round range was a minimum, no adjustments to the transmitter when in operation, and only one tuning adjustment allowed on the receiver. Perfect speech quality with one hundred per cent reliability was demanded, and the maximum aerial length was 150 feet, to be replaced by a fixed aerial if possible.’