These days, King John (1199-1216) is particularly remembered as being forced to sign the Magna Carta by the Barons of England on 15 June 1215. Even after he died, the mood of many of England’s Barons was to invite Louis, the Dauphin of France (1187-1226) – later Louis VII 1223-1226) – and the son of Philip II of France (1180-1223), to rule the country. Back in 1200, John had made a compact with Philip that brought two years of peace but following the signing of the Magna Carta, the English Barons invited the French King to invade.

John called for the help of the Cinque Ports Fleet and they sank many French ships. From the bounty pillaged from French towns by the Portsmen, John increased England’s defences including fortifications of Dover Castle. On 14 May 1216, Louis, the Dauphin of France, invaded but days before, a storm had wrecked the Cinque Ports Fleet. Thus John and the town of Dover were forced to watch as the Dauphin and his army landed on the town’s beaches. Immediately, John left for Winchester leaving Hubert de Burgh (c1170-1243), the Constable of Dover Castle (1203-1232) along with 140 men to defend the by now well-fortified Dover Castle.

Louis and his army marched to London, where the Barons welcomed him. Most of Southern England fell to Louis, but the people of Dover remained resolute. The Dauphin returned to take Dover and the Castle in order to ensure that England was his. To achieve his purpose, he ordered to take the town’s Mayor, Solomon de Dovre, and some of Dover’s Jurats hostage and to burn the town.

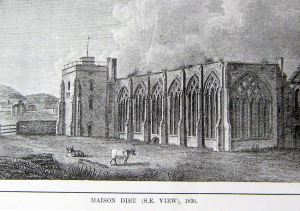

Relief of Dover Castle by John de Pencester 1216 depicted in a windown in the Stone Hall, Maison Dieu. Alan Sencicle

On successfully carrying out these orders, the French soldiers camped in the area of today’s Laureston Place, known as Uphill and a siege of the Castle ensued. Almost starving, de Burgh and his men still held out fighting off the Dauphin’s men. The French then tried to undermine the Castle’s North Rampart Walls in order to gain entry but failed. Famously, de Burgh was reported as saying at this time, ‘I will not surrender; as long as I draw breath I will never resign to French aliens this Castle, which is the very key to the gate of England!’ Eventually, Louis called a truce on 19 October 1216, when, so the story goes, John de Pencester – after whom Pencester Road was named – arrived with reinforcements. However, by that time, King John, had contracted dysentery and died during the night of 18-19 October. He was buried in Worcester Cathedral.

Nonetheless, as John was dead leaving as his successor his young son Henry born 1207, the French, with a massive contingent of re-enforcement set sail to invade England. Hubert de Burgh, at Dover Castle, left the mighty fortification and joined the Cinque Ports Fleet and with the Portsmen sailed to take on the French armada. They met on 24 August 1217 and the Battle of Dover ensued. De Burgh and the Cinque Ports Fleet routed the French Navy and prevented the invasion of England. The young Henry and under the care of Hubert de Burgh as the Chief Justicular of England, as Henry III (1216-1272) was pronounced King of England. Dover was given the accolade, The Gate of England and the Castle, the Key!

Maison Dieu Estate & Stembook Tannery

When Hubert de Burgh was appointed the Constable of Dover Castle in 1203, Dover at that time was a compact town surrounded by walls on three sides. Biggin Gate, near to the present southern end of Biggin Street, was the main northern gate into the town outside of which was farmland on both sides of the River Dour. On the northern end of this land in 1203, Hubert de Burgh established a religious house, run by the Master and Brethren of the Maison Dieu, for the accommodation of poor priests, pilgrims and strangers. They, predominantly coming from and returning to the Continent after visiting the tomb of Archbishop Thomas Becket (1162-1170) in Canterbury Cathedral.

Going east past the north side of St Mary’s Church from the bottom of Biggin Street, these days, is a footpath that wends its way to present day Maison Dieu Road. This follows the route of the ancient right of way, originally called Dee Stone Lane, as ‘D’ was carved into the boundary stone but this was probably changed to Dieu Stone Lane after the Maison Dieu was established. Dieu Stone Lane that went to the Castle and was also, effectively, the southern boundary of the Maison Dieu lands. While on the eastern side was what was officially known as Charlton Back Lane, going to the village of Charlton, to the north of Dover. By the time of de Burgh, the Dour had split into the Eastbrook and Westbrook with the latter turning sharply in a westerly direction roughly where it does today before turning sharply south to the sea. The Dour, from where it turn sharp westerly and then south, was named Stembrook.

The land along the Stembrook was marshy and by 1329 was owned by the Mayor, William Hortin. At that time, on the area near to the ancient Eastbrook Harbour, the town’s shipbuilders carried out their trade. On the west side the ground rose sharply to the Market Place, these days Market Square. There, on the north side of the Market Place stood St Peter’s Church, to which Church Street ran at the east side. From there the ground fell away to marshland and the River Dour. The rise in the topography caused the Stembrook section of the Dour to turn south towards the sea. On this land was the municipal stray animals’ pen where farm animals that had wondered off their owner’s property were kept until the owner claimed them for a fee. Nearby was the extensive Stembook tannery.

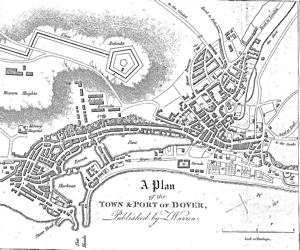

Early 16th century map of Dover. St Peter’s Church can be seen on the north side of Market Square. Ian Cook

In 1343 the decision was taken to extend St Peter’s cemetery ground over the Market Place end of Church Street. This was to last until the end of the 16th century when St Peter’s ceased to exist. In 1590 Thomas Allyn, the Mayor, sold the Church land. Queen Elizabeth (1558-1603) gave authority for the sale, and ordered that the proceeds to be devoted to the harbour and shortly after Church Street became a public thoroughfare again. The footpath that runs along the south side of St Mary’s Churchyard roughly defines the boundary between both Church grounds. At the time, the rest of St Peter’s burial ground became part of that of St Mary’s. Of interest, the Mayor, Thomas Allyn, absconded with the money raised by the sale of St Peter’s Church property!

On the land held by the Hortin family the ‘odious trade’ of tanning, or the making of leather, took place. Traditionally, this was relegated to the outskirts of towns but close to a source of water for obvious reasons when the process is examined. In those days, dry, stiff animal skins would arrive at the tannery dirty with soil and bits of innards still attached. The first job was to remove the horns, which were sold to comb makers. Then a ‘fellmonger’ would scrape the dirt, loose flesh and fat from the hides. These would then be soaked in water to clean and soften them.

The next process was carried out by flayers who pounded and scraped the hides until the entire dirt, flesh and fat were removed. Hairs were removed by soaking the skins in urine, collected by scavengers from the town’s folks piss-pots. This stale urine loosened the hairs and picklers would scrape them off. Once the hairs were removed the skins were soaked in vats of dogs-pooh, again collected by scavengers, and mixed with water.

The tanners kneaded the soaked skins, usually barefooted, in the vats of tanning solution – diluted dogs-pooh etc. This process was repeated many times and could take as long as seven years before the skins became supple. Finally, stretchers pulled the hides into shape on frames, which were then immersed into ever increasingly stronger vats of tanning solution. The hides were then scraped by hand to get rid of the bloom, a white substance, before the skins were hung to dry.

By the 15th century, Dover boasted of a large and thriving leather industry making boots, shoes, gloves, collars, saddles etc. Much of this work was carried out in Last Lane and the immediate vicinity, in crowded ancient streets close to the then St Martin-le-Grand church and former monastery. This was on the opposite side of the Market Place from the Stembrook tannery. At the time, there were a number of other tanneries in Dover and numerous open fronted shops, each with its apprentices and journeymen all involved in aspects of making goods out of leather. Journeymen were effectively labourers having training but only able to work under a master craftsmen who was usually the owner.

From early medieval times in Dover, besides a guild incorporating the different aspects of leather making, there was another craft guild that incorporated glovers, shoemakers, cordwainers, saddlers, collar makers and cobblers. These were fraternities and by custom and the rules of their guild were not allowed to do work in areas that were covered by another craft. For instance, the cordwainer – the maker of new boots and shoes from new leather – could not cobble or mend boots or shoes. Further, crafts had subdivisions and again each had the monopoly of the particular skill. In relation to cordwainers, there were two subdivisions, the solers who made the lower parts of the footwear and the uppers who made the remainder!

Maison Dieu Estate and Private Ownership

Over the centuries the Master and Brethren of the Maison Dieu’s land holdings had extended considerably and included the land between the Mother House and Stembrook. In 1534, Henry VIII (1509-1547) ended all religious functions at the Maison Dieu and ten years later the monks were evicted. The victualling department of the Royal Navy, in 1552, appropriated the building and the lands belonging to the Maison Dieu were eventually sold by order of Parliament in 1650. Except for a large parcel of land used by the victualling department and on which Maison Dieu House was built, the Wivell family purchased the remainder. On this land, named the Maison Dieu estate, they built a fine mansion that faced Biggin Street and the east side of the estate abutted Charlton Back Lane.

Dieu Stone Lane bridge at the south eastern corner of the then Maison Dieu estate now Pencester Gardens. Drawn by George Jarvis.

The estate eventually passed to the Gunman family and by the 18th century Stembrook tannery was owned by Edward Jeffries (d1812). Dieu Stone Lane separated the Maison Dieu estate from that belonging to the tannery and a small stream, that meandered from Castle Hill until it joined the Dour where the Stembrook turned south, provided the southern border of the tannery estate. Opposite, on the west side of the Dour was the remainder of the tannery estate and it was on this site that the tannery was situated. The southern part of the tannery estate was bordered by an ancient footpath that ran from the Market Place to St James Church, at the foot of the eastern cliffs, and then up to the Castle. The footpath traversed the Stembrook-Dour by a ford.

In 1792, just before the start of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), the Market Square – Castle footpath was commandeered by the military along with a corner of land, next to the Dour, belonging to the tannery. On the commandeered land the Board of Ordnance built the four-storey Stembrook mill to provide flour for the great number of troops that were being moved into the town. Also to provide part of the victuals for the crews of the naval ships in the harbour. The Maison Dieu was turned into a massive bake house. The mill adversely affected the tannery’s water supply and it along with the land holdings was put on the market. Humphrey Humphreys, (1772-1863) from Tenterden bought the tannery and land holdings. Using the small stream, he diverted a water supply to the tannery, which subsequently thrived. As more troops moved into the town, the demand for flour increased and the Stembrook Mill was rebuilt and enlarged in 1799 and again in 1813. In1798, Humphreys married Ann Anscombe Clarke and in 1823, Caroline Baker.

To help to pay for the War the government introduced a number of taxes and this included one on prepared leather hides and it became general practice for tanners to use false weights to indicate that the hides were lighter than they really were, thus ensuring he paid less leather tax. Whether Humphreys did this, is not recorded, as he was never implicated in this practice. Instead, he became increasingly involved in local politics and became an active member of the Paving Commission. This had been set up by Act of Parliament in 1778, with the principal function of town management, which included sanitation and lighting. Both of these the Commission tended to be lax at enforcing, indeed with regards to street lighting, this helped the town’s booming trade of smuggling.

A Military Road was laid in 1797 from the Castle to Western Heights, using the ancient foot path from St James Church, past the tannery and Stembrook Mill, through to the Market place and on up to Western Heights. Following the end of the War, this was handed over to the Deal Turnpike Trust and shortly afterwards Humphreys sold a piece of land at the end of Church Street. The new street was named Caroline Place after the estranged wife of George IV (1820-1830), Queen Caroline of Brunswick (1768-1821), cottages were built along it with a large building housing the Artillery Volunteers’ Institute next to the tannery.

When the Napoleonic Wars ended, the country declined into a deep depression, the demand for flour slumped and this hit Dover’s milling industry hard. However, by the end of that decade, things started to look up and with it, the demand for flour, especially in London. Hoys (seagoing vessels) would bring grain to be milled in Dover and then take the flour up to London. The Pilcher family, using loans, bought a couple of mills, one of which was Stembrook and they employed Henry Julius Winter (1766-1841) to run it. At about the same time, a consortium of wealthy local businessmen took steps to convert this part of the Military Road into the residential thoroughfare by buying the section east of the Dour. Most had made their money from running smuggling operations and all were members of the Paving Commission. The land along the former Military Road on the west side of the Dour to Market Square belonged to the Paving Commission.

On this land, the Paving Commission extended the ancient Stembrook thoroughfare with its quaint cottages from Dolphin Lane to the Church Street and Caroline Place junction. To create this extension required purchasing the remaining western part of the tannery lands from Humphreys, for which they paid him £2,000. With this money Humphreys moved to Buckingham, where he styled himself a gentleman. In 1841, 1853 and 1854, Humphreys was elected the Mayor of that town and died on 2 May 1863, aged 93. He was buried in a double depth grave with his faithful servant and friend for 50-years, Mary Ann Andrews (1789-1862) from Hythe, who had died on 8 March 1862 aged 72.

Although the Paving Commision had problems in purchasing land to take the consortium’s road into Market Square, they managed to finally succeed. The bridge we see today was built across the Dour and finally Castle Street, as the new thoroughfare was called and was completed in the 1830s. Shortly after, the Stembrook thoroughfare, on the sea side of Castle Street was renamed Dolphin Place and about 1840 cottages and poorer workers residences were built on Church Place, which extended the Stembrook thoroughfare to Dieu Stone Lane.

Church Place with Flashman’s cabinet factory & Union Hall on Dieu Stone Lane at the end. Dover Library

On Dieu Stone Lane there once was a wool factory that was subsequently taken over as a cabinet factory by George Flashman (1804-1885), who owned a large furniture shop on Castle Street. The top and bottom floors being used for the making of furniture, while the middle floor was known as Union Hall and united religious meetings were held there. For a long time, the Dover Young Men’s Christian Association meetings were held there under the presidency of William Rutley Mowll (1824-1879). In 1894, the activities that took place in the Union Hall were moved to a building that took the same name in Ladywell and following its demolition the former Technical college was built on the site. In 1894, Flashmans took over all of the building on Dieu Stone Lane.

Economically, the 19th century was orchestrated by a series of booms and busts and towards the end of the 1830s the country was heading towards the one of deepest depressions. By 1838, unemployment and subsequent starvation was on the increase and in Church Street lived John Williams, the proprietor of the Duchess of Kent eating house in the Market Place. On one particularly cold and snowy December day he was crossing the Market Place and was distressed to see a number of men standing about, ill clad, with their hands in their pockets and starvation stamped on their pale, wan, faces. Concerned, with his friends Steriker Finnis (1817-1889), Samuel Latham (1799-1866) and others, he set up the Dover Philanthropic Society that raised funds to provide the poor with soup and bread in winter months. The successor to this voluntary service still exists in the town and provides hot drinks and food to the needy all year round.

Humphreys’ son, also called Humphrey, continued to work the tannery and was keen to show off his abilities. In 1851, he exhibited a skin of a boar from Prescott’s farm at Guston that had taken seven years to turn into good quality leather. This was first on show as exhibited at the Great Exhibition in London of 1851 and was 2-inches (5cms) thick. After doing the rounds of various local exhibitions, the leather was sold to George Coulthard (1791-1854) a local boot maker, who used it for the soles of his boots. At the time of the Great Exhibition, Humphreys senior put the tannery on the market and it was sold to William Rigden Mummery (1819-1868), from Deal.

In the meantime, the Gunman estate had come into the possession of George Jarvis senior (1774-1851). When he left the town in May 1827 to become the master of Doddington Hall in Lincolnshire, George Jarvis senior gave his Dover estates to his son, George Knollis Jarvis (1803-1873), known in Dover as George junior. He and his wife, Emily Pretyman Jarvis (1815-1840) lived in the mansion built by the Wivell family on the Maison Dieu estate and continued to maintain the extensive grounds.

The estate formed the eastern boundary of the parish of St Mary-the-Virgin and the time honoured beating the bounds took place there once a year. The occasion was marked by the Town Crier walking down the middle of the River Dour alongside the Jarvis estate to Stembrook accompanied by the Town Council. As they were all in their finery, they walked on the Maison Dieu estate side of the River. Just before the Stembrook Dour left the estate, a large tent was erected and George junior, Emily and their 6-year-old daughter Emily Louisa Harriet, met the party and served them drinks and copious amount of refreshments. On 6 March 1840 Emily, died having given birth to their son, George Eden, born that day. Emily was buried within St Mary’s Church and her memorial can be seen by the north door. Shortly after, George junior move to the Knees in Shepherdswell with the two children.

The break-up of the Maison Dieu Estate

George Jarvis senior died in 1851 and George junior sold all his land holdings in and around Dover and moved to Lincolnshire. A public footpath ran from Biggin Street, across the Maison Dieu Estate towards the Castle and the northern part of the Estate was sold to William Moxon (d1865), who built Brook House. To provide egress into Biggin Street, he built a makeshift bridge across the Dour and applied for permission to lay out housing lots alongside the track.

The Corporation called Moxon’s track, Pencester Street, later changed to Pencester Road, after John de Pencester who had helped to defeat Louis the Dauphin of France at the time of the Battle of Dover in 1216. Not long before, Dover council had purchased the Maison Dieu from the victualling department of the Royal Navy and voted for the building to be glorified as Dover’s Town Hall. Part of the restoration included large stained-glassed windows in the Stone Hall depicting aspects of Dover’s history. About 1850, Edward John Poynter (1836–1919) drew a series of cartoons for the insertion of coloured glass into the window frames in the Stone Hall. One of these depicted the 1216 Battle of Dover and John de Pencester, (see above).

The remainder of the Maison Dieu Estate was sold to William Crundall senior (1822-1888) who intended to build an upmarket crescent of houses that was given the provisional name of Neville Road. He demolished the mansion and laid the road at the west side of the site, but following the opening of Pencester Road abandoned his project. Instead, Crundall built fine detached and semi-detached properties along Pencester Road. In 1856, he bought what had been the Charlton paper mill on Woods Meadow further up the Dour. This, Crundall converted into a sawmill and used the wood from the trees he had up rooted from the former Maison Dieu Estate to get the business going and created a meadow that was prone to flooding. He then dealt with this by planting different types of native trees on the banks of the Dour. Over time, tall poplar trees, copper beeches, and other fine trees flourished there. Using Neville Road as an access drive to the area, Crundall turned the site into a storage yard for his timber and allowed it to be used for school treats. The area became known as Crundall’s Meadow or more commonly Timberyard Meadow.

On the small piece of land he had acquired at the east end of Caroline Place, he extended the cul-de-sac from the Artillery Volunteers’ Institute south towards the back of the Castle Street residences. There he built workers residences for his timber business, much to the annoyance of the affluent owners of some of the Castle Street properties. Later the Drill Hall was built at East Cliff and the Artillery Volunteers’ Institute moved there. The building was then used by a variety of organisations, usually of a philanthropic nature, and in 1872 the Good Templar movement, under the auspices of the late Rev Hugh Price Hughes (1847-1902), took it over when their previous premises on Biggin Street became too small.

For years, the close proximity of Stembrook Mill had made the properties on Stembrook thoroughfare and Caroline Place damp and exacerbated flooding problems in the area. This was stressed by Sir Robert Rawlinson (1810-1898) engineer and sanitarian, who had been appointed one of the first inspectors under the 1848 Public Health Act to report on the sanitary conditions found. He recommended that the mill be demolished but the owner, Willsher Mannering (1814-1853) declined. Shortly after a large triangle of poor quality properties were built opposite the mill with the east side facing the mill, the south side facing Castle Street and the west side facing Church Street, which was widened and not so crooked as before.

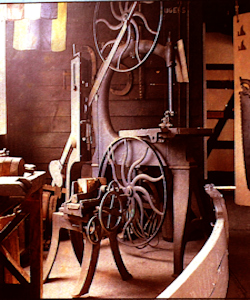

Hides being soaked before removing the hairs using the tools. St. Fagans, National Museum Wales Cardiff. Zurek

William Mummery, who had bought the tannery at the southern end of Timberyard Meadow, was a keen businessman and he introduced many improvements in both methods and the machinery of tanning. These included soaking the hides in limewater pits for about two weeks to soften and to make the hair easier to remove. Once scraped off, the hair was sold to gelatine manufacturers for sizing to be used in papermaking and for domestic purposes. In the tan pits, of which there were three blocks, one containing 65 pits the other two not so many, the skins were tanned. There they were soaked in a solution of ground oak bark and water. The bark was a by-product of saplings used for hop poles and a financial statement of May 1887, the usual time when hop poles were being prepared, shows that about 500 tons of bark was delivered.

The oak bark was milled on the premises and as the hides went through each stage of the tanning process, the ratio of bark to water became stronger. Towards the end, ground Valonea or Turkey Acorn nuts from Silesia were used to strengthen the tanning mixture. Mummery had a specially designed machine of small brushes over which the hides slowly travelled to removed bloom – a white deposit that looks like, but is not, mould, and results from fat being used in the tanning process. The hides were then dried in a large, warm aired, hall and to complete the process they were rolled with heavy brass rollers on a zinc surface until an even density and solidity was obtained.

By 1861, Mummery was employing 21 men and making a name for himself in local politics, being elected Mayor 1865, 1866 and 1867 and living in Maison Dieu House. He died in 1868, at which time the business was taken over by his sons, William (1845-1899) and Albert (1855-1895). William, a leading light in the Russell Street Congregational Church, devoted his life to increasing and maintaining the success of the tannery. Albert, although helping to run the tannery, became World famous as the Father of Mountaineering.

Meanwhile, artist William Burgess (1805-1861), who was arguably Dover’s greatest painter, was living in one of the crowded properties that faced the Stembrook thoroughfare and Castle Street. Burgess had been born in Canterbury and from an early age was encouraged to draw in order to decorate his uncle’s coaches. After a spell travelling around Europe, Burgess married Harriet (c1816-1884) from Deal and settled in Dover eventually moving to 14 Stembrook with a door for customers at 69 Castle Street. His prestigious talent was recognised and exhibited at the Royal Academy and by the Royal Society of British Artists. In 1844, Burgess opened a Cosmorama, which proved a great tourist attraction and brought him further and wider recognition. Indeed, his paintings and lithograph prints of Shakespeare Cliff in the Cosmorama were so popular that that a nearby alley was named Shakespeare Place! William died on 30 July 1861 and Harriet, married local builder Parker Ayres (1810-1885), who had laid out Norman and Saxon Streets in 1846. Dover Museum hold a collection of Burgess’ works and high up on a wall near the corner of Stembrook and Castle Street, is a Dover Society plaque dedicated to him.

Castle Street late 19th century looking towards the Castle. On the left is Stembrook Mill. Dover Museum

What had been known since ancient times as the Charlton Back Lane, which ran along the eastern flank of Timberyard Meadow, in 1863 was widened and renamed Maison Dieu Road. Flooding had been a problem for as long as anyone could remember with many of the older folk blaming it on Stembrook Mill. Albeit, it was recommended that Maison Dieu Road surface be raised by 3 feet (1metre) above the Dour’s mean level. However, the council, or to give it the correct title, Dover Corporation, decided that this was too expensive as flooding only occurred following heavy rain, so nothing was done. Following Willsher Mannering’s death in 1853 eventually his sons Willsher junior (1841-1923) and Edward (1849-1932) took over his mills. About 1870 they sold Stembrook Mill to George Brace, who renamed it after himself.

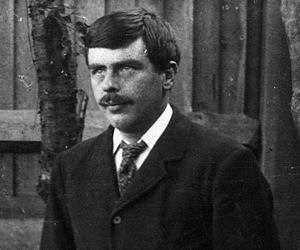

William Crundall junior (1847-1934) in his Mayoral robes – a post he was to hold thirteen times between-1886 and 1910. David Iron collection

By this time Dover was divided into two staunch political camps, the Conservatives, headed by Edward Rutley Mowll with his deputy, William Crundall junior (1847-1934) who took over the leadership following Mowll’s death and was to be appointed Mayor 13 times. Their opponents were the Liberals, led by Richard Dickeson (1823-1900) who had taken an active role in Dover’s civic affairs since he first arrived in the town in 1840. The three men were all self-made entrepreneurs and both Crundall and Dickeson were later knighted. Of note, Dickeson’s legacy to the nation was that his company laid down the foundation for the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes or as it is better known, the NAAFI.

November 1871 saw the start of Dickeson’s first of four terms as Mayor, during which time the Ballot Act of 1872 requiring all elections to be held by secret ballot was accepted in Dover. This was against fierce opposition from the Conservative fraction, as they saw the secret ballot as unmanly, cowardly and was likely to lead to universal suffrage. Because of this discontent, Dickeson was obliged to sign, under the Mayoral Seal of Office, a statement consenting to adhere to the Act. This pushed the two camps further apart and in the municipal elections held in November 1872, the Conservatives won and Mowll was appointed Mayor.

The Timber Yard and the Stembrook Area

From 1872, the Conservatives held power, but in 1879, the Corporation candidates seeking re-election in the municipal elections or standing for vacant seats were returned unopposed. This resulted in the Liberals seizing control by a four-seat majority and they elected Dickeson as Mayor for the following two years and a fourth term in 1882. Dover Corporation immediately adopted a new motto, accepted by both political parties, ‘The greatest good to the greatest number‘ … as long as this did not cost too much! One of Dickeson’s suggestions was the purchase of land on the margin of the River Dour for a longitude pleasure walk – due to a number of reasons, this was not completed until the late 20th century. See River Dour part II the Walk section I and the River Dour part II the Walk section II stories. Albeit, after much debate it was decided to rent the Northfall Meadow, as it was ‘rural and offered a breezy promenade’ and they extend the footpath from Castle Hill to the eastern walls of the Castle, and created ‘a stepped promenade‘ that still exists.

Out of public subscription the Corporation purchased and established Connaught Park in 1883 promising to pay the annual cost of upkeep by charging it to the District Fund in perpetuity. Previously, the Conservatives, in 1878, had persuaded the Dover Harbour Board to open the Granville Gardens, in the centre of the Seafront. The Corporation held them at a nominal rent and maintained upkeep. Following negotiations carried out by the Mayor, William John Adcock (1840-1907), the Danes Recreation Ground, on Old Charlton Road, opened in 1891 and proved not as costly as anticipated so was again greeted with a long term promise for its upkeep. In 1906, the Corporation opened Maison Dieu Public Gardens, situated on each side of the Dour. They were partly laid out as a bowling green and the remaining area, as an ornamental garden.

Map of 1907 showing Crundall’s Timber Yard, which eventually became Pencester Gardens and the site of the Stembrook Tannery. Dover Library

Crundall was running his father’s business affairs by 1880, including the timber business and that year he sold the timber meadow to Sir Edward Watkin (1819-1901). He was the Chairman of the South Eastern Railway Company and was planning to build a railway station on the Meadow for a railway line connecting a Channel Tunnel with St Margaret’s Bay. He had already started the exploration for his Channel Tunnel project near to where Round Down Cliff had once been – now Samphire Hoe. However, in July 1883 a Joint Committee of both Houses of Parliament held an enquiry into the proposed Tunnel but stated that: ‘The majority of the Committee are of the opinion that it is not expedient that Parliamentary sanction should be given to a submarine communication between England and France.’

When the Crundalls realised that the Channel Tunnel project was unlikely to go ahead, William Crundall senior offered to buy the Timberyard Meadow back but at a reduced price. Watkin was forced to accept this by the railway company’s Board of Directors. While those negotiations were going on, Crundall junior offered the site to the Corporation for a new Town Hall. However, the Prison Act 1877 had abolished borough prison jurisdiction and the four-storey gaol on the Ladywell side of the then Town Hall – the Maison Dieu – was demolished. On the site, Dickeson advocated building a Town Hall annex and once he gained power, this was put into action. The result was the Connaught Hall. Crundall’s offer was turned down and he immediately transformed Timberyard Meadow into a business on the renamed Timber Yard.

Thomas Longley of the Star public House, Church Street known as, ‘Her Majesty’s heaviest subject.’ Dover Museum

On Church Street there was long established public house called the Star that was particularly favoured by the nearby market vendors. The hostelry, for many years, was kept by Thomas Longley (1848-1904), known as ‘Her Majesty’s heaviest subject.’ Longley was born in Snargate Street on 13 January 1848 to butcher William and his wife Esther. When he grew up Longley went to work at the Star and for most of his life was the landlord. He was just over 6feet tall and at his heaviest, weighed 46stone, had a chest measurement of 86 inches and each calf measured 26inches! His finger ring can be seen in Dover Museum and gives a good indication of his size. When Longley travelled out of Dover it was always by railway and in the guards van as he was too big to get into the compartments. Longley died on 22 February 1904 and was buried in St Mary’s cemetery. 10 bearers were needed to carry his coffin.

In the late 19th century there was a proliferation of aerated mineral water factories opening in Dover, one of which was owned by Arthur S, Bright (1857-1921). His business was in two cottages, knocked into one, at the Dour-Stembrook end of Caroline Place. When Bright started out, the drink he produced was made up of water, sugar and flavourings and was brewed in large copper pans heated on giant gas rings until the sugar dissolved. The mixture was then allowed to cool and an effervescence, such as Seidlitz powders – a laxative preparation containing tartaric acid, sodium potassium tartrate, and sodium bicarbonate that effervesced when mixed with water. By the end of the century, Bright had probably switched to using carbonic acid gas to create the fizz. This was purified carbonate of lime mixed with an acid and introduced into the drink by the use of an electric generator. Bright also employed retired soldier John Meenagh (c1846-1906) to manage the factory, a position Meenagh held until his death in 1906.

Increasingly the town centre traffic along the narrow main streets from Ladywell to Market Square had been a problem the Corporation had been trying to deal with since 1881. In 1892, they looked at a number of proposals, one of which was the widening of the High Street – Ladywell junction, widening Ladywell and laying a new street behind the Town Hall, across William Adcock’s building yard, to what was still called Pencester Street now Road. From there, across Crundall’s Timber Yard and Caroline Place to Church Street and then Market Square, as the previous Market Place had been renamed. Crundall was at the height of his political powers and the Corporation opted for another scheme that required the widening of both Cannon Street and Biggin Street. This was to enable electric trams to traverse them both, a new mode of transport that required electricity and Crundall was in the process of establishing a private company to generate it.

To enable the widening scheme to go ahead, Parliamentary powers were successfully sought. In Cannon Street, the properties, on the east side, from St Mary‘s Church to the Antwerp Hotel, together with properties on the west side from Market Square to almost the top of Biggin Street were purchased. These cost the Corporation £53,744 including legal fees etc. and were demolished. A competition was held for the design of new imposing buildings on the east side of Cannon Street that we see today. The land on the west side of both Cannon Street and Biggin Street was sold to property developers on the strict understanding that the new buildings would be equally as imposing and would include a grand hotel. During the demolition of the east side of Cannon Street, human remains were discovered from the churchyard of the ancient St Peter’s Church mentioned above.

On 9 November 1895, the Corporation passed a resolution proposing an electric tramway and authorisation was given through the Dover Corporation Tramway order of 1896, which was confirmed by the Tramways Orders Confirmation (no1) Act 1896. Costing £28,000, the first tramway opened in 1897 and was easily accommodated on the town centre’s main thoroughfares. Crundall, however, was still trying to find an alternative use for the Timber Yard and decided to create a cricket ground on the site. Albeit a consortium made up of predominantly Crundall’s political rivals, successfully bought land at Crabble and opened Crabble Athletic Ground in 1897.

Corporation Acquisitions

William Mummery died on 8 January 1899 and Maison Dieu House and the tannery were put on the market in February 1900. The Corporation bought Maison Dieu House for the Borough Engineer and Medical Officer of Health and Crundall, as the Mayor, said that the Timber Yard was still available for purchase. His fellow councillors agreed that the Corporation should buy both the tannery and the Timber Yard, as together they would make an ideal park in the centre of town. However, George Bacon (1852-1936) from Saffron Walden, Essex, bought the tannery and the idea was put on the back burner. Seven years later, in 1906, the Dover Bowling Club that hired the Bowling Green on Maison Dieu Gardens fell out with the owners – the Corporation – when the latter restricted the sale of intoxicating liquors in the grounds. Bacon came to their rescue by allowing the Club to construct a new Green on the tannery land.

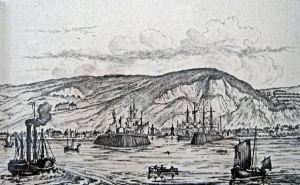

View from St Mary’s Church towards the Gasometer Townwall Street, Stembrook Mill on left 1900. Dover Museum

Albeit, flooding remained a problem, the Corporation decided to try and deal with it. Borough Surveyor, Henry Edward Stilgoe (1867-1943) suggested deepening the bed of the River Dour. In 1901 the Corporation purchased the riparian rights to Stembrook Mill and lowered the base of the River Dour from there seawards through Leney’s Phoenix Brewery to St James Lane, by about 2 feet. Initially this solved the problem but the continual increase in the use of concrete or other impervious materials for road building in the urban area means that this problem still exists. George Brace died in 1904, Stembrook Mill closed in 1905 and was demolished in 1918. The remains of its wheel pit can still be seen below Castle Street bridge.

Tuesday, 4 August 1914 saw the outbreak of World War I (1914-1918), air-raid drills were started immediately and shelters opened. The nearest one to the crowded Stembrook area was in the vaults of Leney’s Phoenix Brewery on the sea side of Castle Street. Throughout the War notices on front line casualties were posted at the company’s brewery offices and many were the husbands and sons of those living in the Stembrook area. Throughout the War, Dover was subjected to bombing raids and just before midnight in early August 1917 German Gotha aeroplanes dropped bombs. The first fell on the Eastern Docks and this was immediately followed by bombs falling in a straight line from there, across the Timber Yard to what was then Union Street. Although the Yard was devastated, the Crundall business was not affected.

On 21 March 1918, following the surrender of the Russians 18 days before, the Germans started their Spring Offensive March-July 1918, in order to try and breakthrough the Allied lines from the Somme to the Channel. From early April their objective was to force the British and Allies back to the Channel ports of Calais, Boulogne and Dunkirk and out of the War. The ensuing Fourth Battle of Ypres (7-29 April), was bloody with an estimated 86,000 German, 82,040 British, 30,000 French and 7,000 Portuguese casualties. During that time Dover’s Military authorities feared the worst, and at their suggestion active steps were started dealing with any emergency that might arise. Alfred Charles Leney (1860-1953), the owner of the Castle Street brewery was appointed Evacuation Officer. The town was divided into ten districts, and every horse, pony, donkey and vehicle was scheduled by the Police Chief Constable David Fox (1864-1924) to be on standby. The official designated Place of Assembly for the residents of the Stembrook area was at the far end of Castle Street even though the nearest designated area was in Market Square. In the event, when it was realised by the German High Commend that the Offensive was not going to achieve its objective, it was called off.

Russell Bavington Jones (1875-1949), the Editor of the Dover Express. Bob Hollingsbee Collection Dover Museum

The War ended on 11 November 1918 and two years later the Corporation were considering the future of the Timber Yard, which Crundall was talking of selling. The Kentish Express of 1920, suggested that Dover should be built up as a naval base and strong military garrison and that the Dour should be dammed with Biggin Street and Folkestone Road to be turned into a large inland dock. Although the Dover Express did not concur with the latter suggestion the editor, Russell Bavington Jones (1875-1949) did agree that Dover should become a strong naval base and military garrison. He also agreed that the Dour should be dammed to provide inland docks but these, the editor Bavington Jones argued, should be on the Crundall Timber Yard!

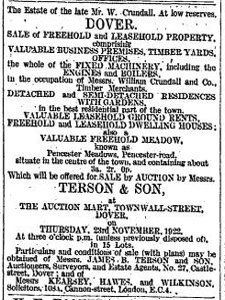

By 1922 the country had rapidly slid into yet another post-war depression. Bacon, on his 70th birthday in 1922, put the Stembrook tannery up for sale and the Corporation purchased part of the site for approximately £1,100. The adjacent neglected Crundall Timber Yard was offered for sale by auction on 31 October 1922. Made up of 15 lots under the general title of Pencester Meadows, the Timber Yard was listed as a separate lot. Another lot listed was Neville Road, that Crundall senior had laid out in 1854, on the west side of what became the Timber Yard but had never built the proposed development. The vendors were the heirs to Crundall senior’s estate and the sale took place at Thomas Achee Terson’s (1843-1936) Auction House, Townwall Street, on Thursday 23 November. Earlier that month William George Lewis (1850-1924), had been elected to the office of Mayor and it was generally understood that his prime concern was to pursue projects that provided employment – at the time there were 1,400 men out of work in Dover.

The Corporation was well aware that to try and combat the increasing unemployment the Government, through the Ministry of Health, was making grants and loans for council sponsored projects as long the outcomes had long term positive outcomes and provided work. Mayor Lewis and the Corporation reasoned that the former Timber Yard, together with the tannery, could be laid out as a municipal park. This would provide work and a much needed recreation area in a densely populated part of town. Although, at the time, they were unable to put in an application until they had purchased the site, they rationalised and the council unanimously agreed that as the project fell within the Ministry of Health’s criteria, they would get a grant or, at least, a long-term loan. Thus, they would put in an application after they had successfully purchased the Timber Yard.

The lot appertaining to the Timber Yard was given as 3.125acres and the Town Clerk, Reginald Edward Knocker (1871-1956) told Mayor Lewis that before taking the project further he would contact the District Valuer, Benjamin George Turner (1882-1951) for his opinion. Turner was sorry to tell him that the Ministry of Health would not allow him to investigate the sale or provide an opinion as no State money was as yet involved. The decision therefore rested with Mayor Lewis and the councillors. Although they were unanimous as to the purchase they could not agree on how much should be paid. Knocker suggested up to £7,000 but the councillors eventually agreed to between £4,500 and £5,000.

The councillors also agreed that the Corporation would hire an agent to act on their behalf and that they would also hire a sub-agent who would be incognito. The official agent would bid up to £3,900 but if unsuccessful would not increase the bid. Instead, the sub-agent would quietly join in the fray and the principal agent would only return to the bidding contest if, in the event, it went past £5,000. The agent hired was solicitor Sydenham Armstrong Payn (1869-1939) and the incognito sub-agent was a Mr Day the clerk in Mr Wilks solicitor’s office at Deal.

The day of the auction came and due to the considerable interest, the sale room was crowded. By that time, the gossip was that the Timber Yard would go for £3,500 and it was generally known the Amstrong Payn was the Corporation’s agent. The bidding opened at £3,000 for the 3.125acre Timber Yard and it quickly rose to £3,900, with several bidders and Armstrong Payn dropped out of the fray. Day eased in and as no one realised that he was the council’s agent, the number of bidders started to fall away such that when he bid £5,000, no one offered a higher bid. The next lot auctioned was the former Neville Road site, as no one seemed to know where that was, there was little interest and it sold for just £600.

Immediately after Mayor Lewis and Town Clerk Knocker put in the application for a grant to the Ministry of Health. This was for £7,910, made up of £5,000 for the Timber Yard and £2,910 for laying it out to specifications given by the Borough Engineer, William E Boulton Smith (1883-1975). Mayor Lewis and the Corporation reasoned that the Health Minister, Sir Arthur Sackville Trevor Griffith-Boscawen (1865-1946), would look kindly on the project especially when on 27 November the Ministry issued a circular saying that District Valuers were authorised to undertake valuations when councils were applying for loans and grants.

However, local feeling, fuelled by the editor of the Dover Express, Russell Bavington Jones, was against the purchase of the former Timber Yard. The letter writers said that the Corporation had hired two men, one incognito, to act of their behalf at the auction and that both men had bid against each other. Further, the bidding dual continued until the Corporation’s official agent backed down at £5,000 and thus the price paid was far greater than it should have been. Someone else wrote that Sir William Crundall, the former Dover Mayor and more recently the Chairman of the Dover Harbour Board, was the sole owner of the Timber Yard. Others agreed, adding that in 1904 Mayor Lewis had been suspended from being a Councillor again for being involved in bribery with Crundall. It was only by nefarious reasons that he was re-elected and therefore should not be trusted.

Edwin Chitty, the Dover Solicitor, who had successfully brought the case in 1909, over which Lewis had been barred from holding municipal office for three years, wrote that in 1909 bribery was standard practice in Dover elections. Following the case there had been changes within the local political parties such that bribery was no longer a problem. However, like most other people in the town, he was unhappy about the two agents of the council bidding against each other at the auction, which resulted in the price being far greater than it should have been. Others waded into the fracas, in essence saying that the auction had provided a handsome profit for Crundall.

Bavington Jones agreed with much of what was being said and under the headline ‘Pencester Meadow Scandal‘, published the details of a council meeting, where it was evident that a number of councillors had distanced themselves from the project. In an editorial, he wrote, that if the Ministry saw fit to give the Council a grant or a loan, this should be used to pay the unemployed to repair the town streets that were in a bad state of repair and other such projects. As for a children’s playground in the centre of town, Dover had a long Seafront and beaches on which the children of Dover could spend their leisure time. Because the general local feeling was so strong against the project, Griffith-Boscawen ordered a Public Inquiry.

Council Chamber in the Maison Dieu, the former Town Hall, designed by William Burgess in 1867. Dover Museum

This was held on 16 March 1923 in the Council Chamber of the then Town Hall now the Maison Dieu. The Ministry of Health Inspector, M K North presided and the room was crowded. Town Clerk Knocker was the first to give evidence and said that the council had first discussed purchasing the land on 31 October 1922, when they heard that it was coming up for auction. He then gave his account of events that subsequently took place and told the Inspector of the 27 November circular. He then told of the presentation of 3 December, when Turner, the District Valuer, gave his report, saying that £5,000 was a fair price to pay for a 3.125acre site. This drew heckles from the audience in the Chamber. Knocker then detailed what Turner had said next.

On inspecting the details provided by the vendor, Turner had told Knocker and Mayor Lewis, it was evident that the price paid by the Corporation had included Neville Road and adjacent housing lots, that Crundall senior had planned back in 1854. On checking with Terson’s, Turner found that the vendors had insisted it should be sold as a separate lot. Taking that site out of the equation, the Corporation had only purchased 2.3acres, which Turner valued at £3.500! There was uproar in the Chamber before North managed to restore order.

Knocker went on to tell the Inspector that barrister Henry Tindall Methold (1869-1952), was consulted and his opinion was that the Terson Auction House could not be held to account. However, a claim could be sought against the Crundall estate over the Neville Road site as ‘an abatement in the price paid, due to the site being sold as a separate lot‘. On relaying this to Mayor Lewis, Knocker was instructed to take action against the Crundall estate and after heated negotiations with their legal representatives, the Corporation was refunded the £600 that they had received for Neville Road site. By this time audible anger was being express and shouts that Mayor Lewis was in league with Crundall and that they were both crooked.

Boulton Smith was next to be questioned and in response to the Inspector’s query about what the Corporation proposed to do with the site, he said that a special committee had been instructed to deal with the Meadow as an open space. They had further instructed him to lay a children’s’ playground, on the opposite side from the River Dour, for there to be male and female public conveniences (lavatories) at the southern end of the Meadow and at the north, a shelter and a store. Diagonally, across the Meadow he was to lay two auxiliary paths providing access between Dieu Stone Lane and Pencester Road with a circular promenade walk in the middle. All of these works, he had originally estaimated this would cost £2,910 but because of inflation he estimated it would cost £2,940 but that it would provide 3 months work for 50 unemployed men. Upkeep would be ongoing and require a caretaker, seeds, bulbs and general maintenance, which would be approximately between £100 and £150 a year.

Armstrong Payn, the principal agent for the Corporation at the auction gave his account of what had happened there. He also made it clear that both agents representing the Corporation were well aware of the other’s presence and had not bid against each other. The audience were not convinced and loudly heckled him.

The presiding chair and in front, the Flashman lectern in the former Council Chamber where Inspector North would have sat. AS

Finally, Mayor Lewis stood, gave his name and designation but before he could say another word, he was chastised by Inspector North over sanctioning for two agents at the auction and for making such a bid without applying for a grant first. The audience were delighted and cheered loudly. Lewis acknowledged the reprimand and apologised to the Inspector on behalf of the Corporation and then added that only days later the Ministry of Health had changed the policy which would have legitimised some of their actions. This brought the loudest protestations from the attendant audience so far and the Inspector had to bang the Flashman lectern, in front of him, several times with his gavel.

When quietness resumed Lewis said that at the time unless the Corporation actually owned the land, they would not have been eligible to apply for a grant or a loan from the Ministry of Health. This, he added, was to change several days later, after the site had been bought. The only way available to them to secure the land was to buy it before permission for a grant or loan had been granted unless some kindly person lent them the money in the interim. Someone yelled, why had they not asked Crundall, he was wealthy? Before Lewis could answer, the Inspector called for the protester to be removed and made a general warning to that effect.

In answer to why the Corporation were so interested in securing the Timber Yard site, Lewis said it was the only green space in an area of high housing density. The area from Dieu Stone Lane to the Seafront, from Pencester Road to the bottom of Crabble Hill and from Biggin Street westward, including Mount Pleasant and Tower Hamlets, were all densely populated. Further, the elementary schools serving these areas had extremely limited amount of playground space. If the Corporation were to undertake the proposal then the rates would have to be increased to pay for the land, equipment and the unemployed men’s wages. Hence the need for a grant or loan.

Seafront Railway loco No.3102, a P-class 0-6-0 tank-engine on the Seafront in front of Waterloo Crescent c1955.

Mr Bavington Jones, the editor of the Dover Express, Lewis said, had told his readers that as Dover had a long Seafront and beaches there was no need for a green open space in the centre of Dover. What he failed to say, was that the War Office had laid the unhealthy Seafront Railway in 1918 and following the War, the Dover Harbour Board, under Chairman Crundall, had acquired the railway line with the intention of covering the Seafront with docks, warehouses and industrial developments along its course. Lewis added that the Dover Harbour Board were applying for permission for the developments to go ahead in conjunction with the Channel Steel Company’s proposal of taking the Railway Line over the Eastern Cliffs and demolishing homes at East Cliff and Athol Terrace to do so. This raised loud heckles of anger about that proposal from the audience when the Inspector appeared to indicate that he was not convinced.

Inspector North finished the Inquiry by saying that ‘the land had been bought and it is a question of crying over spilt milk for the conveyance is actually settled. In this case the land was purchased at auction so there is a good deal of excuse for what has been done; but the real irregularity was the inquiries as to the size of the land were not made before but afterwards. I want to make it clear that the Corporation were faced with either having to purchase the land or see it pass into others hands.’ He told Town Clerk Knocker that he would send his decision after discussing it with the new Health Minister, Neville Chamberlain (1869-1940).

The report and recommendations arrived a few days later and approval for the project was given! The provisions to be provided by the Ministry of Health included a £2,900 loan repayable over 20 years for Pencester Meadow to be laid out as a play area and gardens. Also consent for a £4,200 loan, repayable over 50 years, towards the £5,000 cost of buying the Meadow. Although the Corporation was jubilant they were still required to find £200 towards the cost of the site, this Mayor Lewis personally covered.

Work began in 1924 on the site which had been renamed Pencester Gardens. Mayor Lewis, however, never saw the project completed for he died on 2 May that year. His old adversary, Edwin Chitty, gave a moving eulogy in which he said that Mayor Lewis had given many benefactions and kindness to the poor people in the town including, most recently, providing work for the unemployed and an open space for the town’s children.

Stembrook Tannery to Pencester Gardens Part Two tells the story of the area up to the present day.

Presented: 05 April 2018