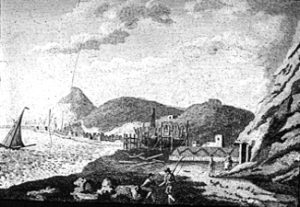

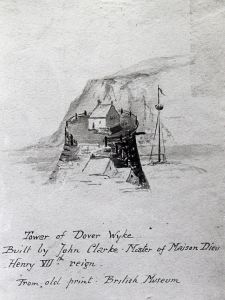

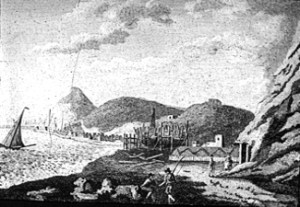

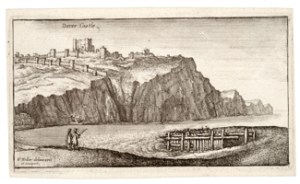

Dover Harbour c1590 on completion of Thomas Digges improvments drawn c1836 by Benjamin Worthington . Dover Library

Part I of the Dover shipbuilding story covered the development of shipbuilding from the Bronze Age (2,100BC to 700BC), to the beginning of the 18th century. During that time there had been some highs, notably in the Bronze Age that left the town the legacy of the Bronze Age Boat – the oldest sea going craft in the World! From the late Saxon era, for some three hundred years the Cinque Ports ships, which included those from Dover, ruled the west of Europe seas. There were also the lows of the late Medieval, Tudor and Stuart era’s, particularly during the reign of Charles II (1649-1685). Albeit, towards the end of the 17th century the Dover ship building industry was given a new lease of life and ships built in Dover were recognised as the best.

It should be noted that the details of most of the ships featured in this golden age came from the work of Mark Frost the former Assistant Curator of Dover Museum, for which we give him and the Museum thanks. Papers held by the Local Studies Archives at Maidstone have augmented this research, and much of this information flies in the face of some accounts that can be read on the Internet. This may well cause confusion to readers and we can only leave it to them to draw their own conclusions.

Anne (1702-1714) became queen of England and of Scotland on the death of her brother-in-law, William III (1688-1702) and was immediately popular. On 22 July 1706 the Treaty of Union united England and Scotland creating the United Kingdom of Great Britain and this came into effect on 1 May 1707. Immediately, maritime trade took on an important role for the economy of the country as a whole. Over the following years the techniques of shipbuilding was perfected and this included those by the individual Dover shipbuilding enterprises. During that century, the galleon gave way to the larger, faster and more slender vessels for the Channel crossing.

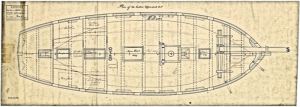

The diagram opposite comes from the Observers Book of Ships by Frank E Dodman (c1950) and shows the masts and sails of a Topsail Schooner. The rope on these ships was mainly used for rigging, a skill that was usually undertaken by sailmakers and ropebenders. Rigging tended to be divided in two types, Standing rigging, which helped to keep the masts in their permanent positions and Running rigging that controlled the movement and position of yards and sails. As can be seen from the diagram, the names of the sails come from the names of the masts to which they were attached.

Besides the main and mizzen masts, a four masted barque also had fore and jigger masts, while the fifth mast was sometimes called spanker or pusher mast. Other aspects to be noted of sailing vessels is that a lift takes the weight of a yard or boom, halliards – also written halyard – raise or lower a spar or sail, braces control the fore-and aft movement of the yards and the clew lines lift and lower corners of a square sail. To bend a sail was to attach it to the yard or boom, and to furl it was to secure it temporarily to a spar by short lengths of line called gaskets. Finally, a full-rigged ship was a sailing vessel with yards and square sails on all masts.

Changes to sails started in the early 18th century to meet innovations in ship design. The triangular headsail was introduced and a similar type of sail (staysail) was set on stays between each mast. Typically, the frigates had three head sails and six staysails and a small square spritsail under the bowsprit. The top spritsail that had been developed for the earlier galleons disappeared. The shape of the mizzen lanteen shaped sail gave way to a gaff style sail and side extensions were added to the top and topgallant sails. These changes were introduced on coastal trade, the ships designed to carry commodities from wood to coal but primarily corn. Smaller fishing craft were also being built and made stronger to withstand the heavy seas off the east coast and the Channel.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the Cullen and Kempe were the main shipbuilding families in Dover but by the turn of the 18th century they had been joined by Thomas Dawkes (poss.1641-1705), a relative of Richard Dawkes, who captured the Castle from the Royalists in 1641. An illustration of the growth in Dover’s ship building industry that was beginning to generate wealth was shown in Dawkes Will of 1705. He gave the Mayor and Jurats of Dover £50 to be invested and from the interest, the poor of St Mary’s parish were to receive bread on St Thomas’s day (3 July).

Members of the local wealthy Kennett family ran another ship building enterprise. For a long time the Kennett family had owned land to the south and west of Biggin Street, farmed by James Cannon, Mayor in 1716. By that time Mayor Cannon had bought the land and laid out Cannon Street that still exists today. Another branch of the Kennett family hailed from Postling, near Folkestone, where Basill Kennett was the vicar. His mother, Mary, was the daughter of Thomas White, a wealthy Dover master-shipwright and his brother was White Kennett (1660-1708) the Bishop of Peterborough. It was the sons of Basill Kennett, with the help of Grandfather Thomas that started a Dover shipbuilding operation, one of which was Matthew Kennett (b1670). He also took an active role in Dover politics becoming Mayor in 1724 and different members of the Kennett family were to continue to hold municipal offices in the town until 1857.

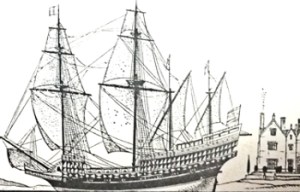

Ship building showing various types of ships that were built at the time. Many of which were built at Dover. Welcome Foundation Wikimedia

Thomas Ladd (1) was born in the 1670s and trained as a carpenter, possibly in another town for in 1715 he was granted the Freedom of Dover by order of the Common Council. The original Freemen of Dover earned their living from the sea and owning their own boats. Over the course of time the Dover Freemen amalgamated with those from Sandwich, Hythe, Romney and Hastings to form the Confederation of the Cinque Ports. The Confederation received a Charter from Edward the Confessor (1042-1066), which gave them rights including freedom of movement, freehold of property, free to run a business and take apprentices for seven years, in other words the convention of Dover Freemen was born. By the time of the Norman Conquest (1066), fewer than half the adult males in the town were Freemen and that ratio would not change for over 600 years. Non-freemen were described as foreigners and had few rights. Freedom could only be obtained by birth, marriage, and apprenticeship, purchasing a freehold and by redemption – an expensive gift to the town.

Gaining his Freedom of the town, enabled Thomas Ladd to set up his own business and by 1730 he had opened a shipyard on the Shakespeare Beach alongside all the other shipbuilders of Dover. By that time, up to 300 ton ships were produced in large, sophisticated shipyards all with teams of qualified workers. They either worked directly for the shipbuilders or on their own account selling their expertise or/and products to the shipyards. They included draughtsmen, wood turners, joiners, iron founders, blacksmiths, sailmakers, ropemakers etc (see Part I of shipbuilding). Thomas Ladd’s two sons, Thomas (2) (1718- 1776) and Henry (1728-1790) were apprenticed to him, with Thomas gaining entry to the Freedomship in 1739 and Henry in 1749.

Roseau figurehead owned by Richard Mahoney and typical of the figureheads produced in Dover. The Roseau comes from the 371 gross tonnage, wooden barque, Roseau built at Jersey in 1857 by F.C.Clarke for Scrutton and Co of London.

Like the other shipbuilders in Dover of this time, the Ladd family particularly made ships for merchant shipping trade as well as the Channel crossing and for fishing. These only differed to meet the needs of the ships’ usage, further, most could easily be converted into warships as needs necessitated. In design, the ships top deck was sheer or curved towards the bow and reduced in area but the forecastle and poop were higher than the waist while the poop was lower than the forecastle. The Dover ships were decorated but this was not as flamboyant as in the past. Instead the painted designs were simple and elegant and ship decorating developed into one of Dover’s expert crafts. As the century progressed, Dover art studios also included carved ships figureheads in their portfolios.

In 1732 another two shipwrights jointly opened a shipbuilding yard on leased wasteland close to the harbour’s South Pier. They were Thomas and his relative William Pascall, the latter born in 1708. They had both gained their Freedom by apprenticeship and recognising the increasing demand for Dover produced ships, theirs was a shipyard producing similar ships to others bring built on the town’s beaches. Nonetheless, their ships proved popular and to meet the increase in demand, in 1751 Thomas Pascall leased more land on Fishermans Row, in the Pier District. As their shipyard expanded, the two men trained apprentices, most of whom it would appear, were members of the Pascall family.

Towards the mid 18th century the Dover shipbuilders were building an increasing number of larger ships, mainly for the merchant shipping markets such that local merchants set up their own shipyards. One of these was Isaac Minet (c1677- 1745), whose shipbuilding yard was situated at the north-east corner of the harbour and in 1738 he launched the Expedition. This was one of several ships built at that time and probably replaced an older one of the same name but it is particularly remembered as it is one of the rare examples where the name of the ship was recorded. Occasionally Dover shipyards put in bids to build ships for the Royal Navy but they were never successful as the government war ships were built at the Royal dockyards of Portsmouth (founded 1496) Woolwich (founded 1513) and Chatham (founded 1547). If they required further shipping, the Admiralty would commandeer merchant ships and adapt them for their needs.

Wars of the Austrian Succession 1740-1748

This situation changed in March 1744 when war was declared between England and France during the Wars of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748). From April that year Letters of Marque could be bought and Dover’s shipbuilders, mariners, merchants and ship owners quickly took advantage of them. Letters of Marque were issued by the government and allowed private citizens to seize goods of enemy nations’ ships as a prize for making war on them – called privateering it was a legal form of piracy! To be successful, the ship owners needed fast ships and the Dover shipbuilding industry specialised in building ships for this purpose.

Keels were laid down on the beaches and the ships were built of the best English oak, Quercus Robur that could withstand the fiercest of gales. A typical ship required a quantity of timber equivalent to some 40 acres of woodland and the oak trees were specially grown, with continual conservation of the species in mind. The woodlands were close to Dover and Waldershare and Lyminge forests still survive. The design of these ships was streamlined in order to provide a speed that could outstrip the speed of most other vessels. The Dover ships especially built at this time for privateering included the New Eagle – Captain John Bazely (1699-1763) – father of Admiral John Bazely (1740-1809); the Carlisle – Captain William Owen (b1704) the York – Captain Gravener, Endeavour – Master Thomas Kennett, the Hardwicke – Commander James Samson (b1687), the Cumberland and the Kingston.

The New Eagle, Carlisle and the York were paid for out of contributions from a large number of towns folk plus the proceeds earned by Bazely on the second-hand ship, Eagle, bought by Bazely and Peter Fector (1723-1814) for privateering. The trio of ships earned a great deal of respect as well as considerable financial returns from privateering to the town’s folk that had contributed to purchasing the three ships. The Endeavour was also built on Dover beach and fitted out in July 1746. The ship’s master, Thomas Kennet, who was particularly famed for equally sharing out booty taken by privateering between his officers and men. One of the lower Buckland mill cottages on the present London Road was converted into the Old Endeavour pub about 1847 and named after the ship. Later the adjacent row of cottages were named Endeavour Place and the nearby present pub recognised the origin of its name in 1982, when Gaskin’s, the local glassmakers, were commissioned to make a stained glass window featuring the Endeavour. Sadly, this was removed sometime ago and the present owners have no knowledge of where it went.

James Boyton (1726-1803), Dover’s Chief Revenue Officer from 1743 to 1756, described another engagement typical of those that Dover privateers were involved in, writing ‘(The) privateer engaged 2 French privateers for 6 hours. He was obliged to pull away – he had four men killed and 9 wounded. The vessel is very much shattered … One of the French had 20 guns and the other 16; he had but 14 guns and 100 men. This privateer helped fight a 20 gun ship in the Calais Road … and had all his masts shot away, but was not taken’ Earlier in 1746, John Latham (1723-1801), a prominent local shipowner held an auction of goods taken from the captured French ships the Dauphin, Periait, Reynaird and Esperance. The list included ‘250 Muskets; some Pistols, Cutlasses, Cartouche-Boxes, Bayonets, Buss-Belts, Pole-Axes, Tents; Beef, Pork, Bread, and sundry Water Casks.’ However, the privateers, New Eagle, Carlisle, York and Endeavour came to the attention of the Privy Counsel who ordered for the ships to stay in port and their sails to be taken ashore. This, it was said, was on the orders of the East India Company and the ships stayed in Dover until May 1746, when they were taken into the King’s service.

On 23 July 1746, under the overall command of Admiral Edward Vernon (1684-1757), the New Eagle, Carlisle, York and the Endeavour played an important part in defeating a threatened invasion by the French based in Dunkirk. The Dover privateers captured several French transport ships that were taking soldiers from Dunkirk to Calais and Boulogne, on board of which was a great quantity of ammunition and provisions. There were also gun carriages and on one ship there was a fine brass mortar and gun as well as a large quantity of chevaux de fris. These were long poles with sharp spikes at one end that were usually placed around horse corals in military camps. The captured French soldiers were taken as prisoners to Dover Castle, where Prisoner of Wars were usually kept at that time. Of note, although the evidence that Dover Castle was used for this purpose during the Wars of the 18th century and including the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815), some PhD students have gone to great lengths to negate the hard evidence!

On 8 April 1747, the York privateer under Captain Gravenor engaged with the two French privateers for six hours. He was obliged to give up when the York’s masts were shot away and was generally badly damaged plus four of his men had been killed and nine were wounded. Of the French privateers one had 20 guns and the other 16, while the York only 14 guns and one hundred men. The smaller French ship was a dogger privateer that came out of Calais to assist the first French ship and she initially managed to capture the York. But Gravenor and his men managed to get the York away and eventually they managed to get to the safety of the Margate Roads, off Deal. For this Gravenor was praised by Admiral Vernon in despatches.

Seven Years’ War 1756-1763

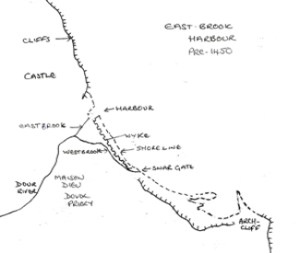

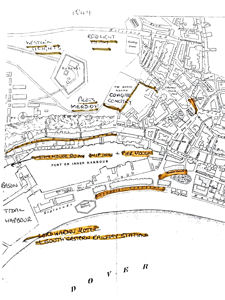

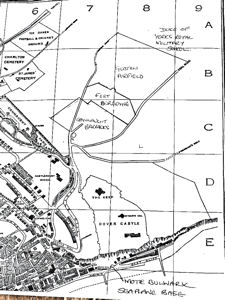

By this time the Royal Navy looked with more than a passing interest at the ships that were being built in Dover and placed orders. Dover’s shipbuilding and associated businesses boomed but completion was hindered by problems in the ropemaking industry. The ropewalk on the main Dover beach was subject to tides and flooding. In 1752 the Harbour Commissioners started to erect a seawall from under the Castle cliffs along the seashore westwards and the ropewalk was in the way. Ropemaker, John Goodwin, on his suggestion was given leave by the Dover Harbour Commissioners to enclose a piece of ground or beach on the town side of the seawall, at his own expense. This new ropewalk was to be free of any encumbrance for 20 years after which Goodwin was to pay a sess or rent as deemed befitting by the Commissioners. The area Goodwin chose was above the sea at Archcliffe above Shakespeare Beach thus closer to the shipbuilding industry. On taking over the ground, Goodwin covered the area with chalk and then with mud out of the Pent and when this had settled he erected the wooden hurdles on which the hemp rope rested while being made by the ropemakers (see Part I of shipbuilding). The Ropewalk housing development now occupies the site.

Once the problem of a continual supply of excellent quality rope was assured, the shipbuilders were able to fulfil all of the Royal Navy’s requests. Many of these ships were four masted yet their keels were laid down on the beaches. The ships built for local demand tended to be smaller in size but of designs that emphasised speed and of a similar quality as those for the Royal Navy. New ships were expensive but the War, through privateering, had created a number of very wealthy families in Dover and generally most households prospered. Many new businesses opened some offering goods that rivalled those sold in the main retail streets of London, Paris and Bath. The centre was the Snargate Street area of the Pier district, at the west side of the town and close to the harbour. Albeit, following the end of hostilities the Government sold many of their ships at much reduced prices, which flooded the shipping market. This had a direct negative effect on private shipbuilding ports along the southern and eastern coast – with the exception of Dover!

Dover ship owners expanded their fleets with these large cheap ships and many of the mariners clubbed together to buy shares while, in some cases, whole families contributed to buying one of the second-hand Dover built ships. They then used their expertise by participating in smuggling businesses. The crews were mainly made up of mariners drawn from the post-war economic depressed Kent towns. This frequently caused discontent between different groups but the threat of harsh punishment by the heavy handed Dover employers was offset by the size of the purses the men received following a successful operation. Although not so many new ships were built at this time, work adapting ships for smuggling purposes was lucrative and the more ingenious the adaptation the more they could earn. Typically, masts were carefully hollowed to provide hiding places, beautifully carved wooden cabinets would have disguised drawers, while tight fitting partitions giving the impression that they butted against a wall would sometimes hide small rooms. Mansions and ordinary homes were also adapted to hide contraband and the operations thrived.

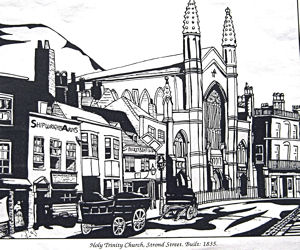

John Bazeley, Mayor 1762 ordered the demolition of the Medieval Biggin Gate. A plaque placed in 1896 can be seen in New Street. Alan Sencicle

Further, in order to try and combat Dover’s growing smuggling operations and well aware that Dover built ships could easily outrun Revenue Cutters, the government imposed restrictions on the number of ships that were built at Dover. This increased the expertise in adaptation of second-hand ships, not only in hiding places on the ships but also in the speed that they travelled through the water. Called reconditioned ships, one such typical vessel was a privateer taken from the Spanish at the beginning of the Wars of the Austrian Succession. She was mounted with four carriage and twelve swivel guns and became the lead smuggling ship for a consortium made up of John Bazely, Peter Fector and Rooth Colebran (c1720-1781) and was reconditioned and fitted out by Thomas Pascall and his son John, both of whom also had shares. Of note, John Bazely was the Mayor in 1762 and gave permission to remove the Medieval Biggin Gate – a plaque placed in 1896 can still be seen in New Street. The ship worked as a privateer and took many prizes and on one occasion three doggers – single masted fishing boats – loaded with brandy off Calais.

By the time of the Seven Years’ War (1756-1763), Dover was the major base for smuggling but with the chance of making more money from privateering, ships were quickly converted on Dover’s beaches. By this time the town’s shipbuilders were illegally turning out new vessels ranging from 20 tons to 150 tons burden that were paid and fitted out for the increasingly prosperous Dover merchants and London investors. Such was the growth that the government introduced more legislation, the Privateering Act of 1759, aimed at stopping the owners of ships that were less than a hundred tons and with a company of fewer than forty men claiming Letters of Marque. This led to an increase in the number of consortiums to purchase larger and faster Dover built ships and these were so impressive that the Royal Navy increasingly procured them!

Following the Seven Years’ War another, and possibly the most famous of the Dover shipbuilding families, started a business on Dover beach. This was the King shipyard founded by Thomas King (1739-1815), the son of William King, who by virtue of his marriage to Ann West, daughter of Freeman and mariner, William West, had gained his Freemanship. Thus Thomas claimed his Freedom by birth and after serving a shipbuilding apprenticeship in Dover, courted Ann Wellard (1735-1796) whom he married in 1764. Ann’s wealth provided the capital for the business and they specialised in the production of cross-Channel packet ships and coastal smacks. The firm prospered and the couple had five sons and two daughters. One of the daughters married into a shipbuilding associated family and the sons served as apprentices in the family shipyard. The two eldest sons, Thomas Jones King (1765-1818) and John King (born 1769) joined their father and the King shipyard expanded. Eventually, it covered the area from the remains of the present day Prince of Wales Pier westwards beyond the Admiralty Pier and lorry parks that now litter Dover’s Shakespeare Beach seafront, to where the Mulberry Tree Inn once stood.

On 25 Sep 1787 Ann West King (1767 -1818), the other of Thomas’s two daughters married William Knocker (1761-1847), the founding father of one of Dover’s major legal families. He was a key member of his family smuggling business that operated around Seasalter, seven miles east of Faversham and also at Heron – probably modern day Herne, near Reculver, then on the north Kent coast. By this time a number of wealthy Dover merchants and their families had smuggling domains around East Kent including the Bazely, Colebran, Latham, Rice, Sampson and Hammond families. However, the main smuggling family was the Fector’s whose operations were refined by John Minet Fector (1754-1821) following the American War of Independence (1775-1783). Of interest, the centre of their operation in Dover was from Pier House on Custom House Quay next door to the Custom House!

American War of Independence (1776-1783)

In an attempt to try and combat smuggling, the government invested in more Revenue Cutters, many of which were built on Dover’s beaches, sometimes next to specially designed smuggling ships! The government also increased the number of Riding Officers but it was the American War of Independence that was more successful in reducing the illicit trade. For this War, the Letters of Marque were not restricted as they had been in the Seven Years War and the Revenue Cutters were redeployed for military purposes. Shipowners used the opportunity to play a robust part in privateering for as records show, the, Dutton, an East Indiaman running out of Dover made £30,000 in profits from only three privateering voyages during this time! In February 1796, the Dutton was at Plymouth when a storm blew up that put the ship aground in Plymouth Sound. At the time, she was commissioned to take transport troops to the West Indies. Although the officers and most of the crew had managed to get ashore, the ship was breaking up with some 500 people, including a skeleton crew and women and children aboard. Famously, Dover born, Admiral Edward Pellew, 1st Viscount Exmouth (1757-1833) organised two rowing boats to carry hawsers – heavy ropes for towing and mooring. A large and powerful man, he swam to the stricken vessel, still dressed in full uniform including sword and instructed the crew to haul the ropes on board and once secured the passengers and crew was winched to safety.

One of the first Dover ships ordered by the Admiralty following the outbreak of the War was from the Ladd family of shipbuilders. This was the Alert a 183ton, 14gun Cutter designed by Sir John Williams, Surveyor for the Royal Navy 1765-1784 and was one of the original pair of his design. The other was the Rattlesnake built by Farley of Folkestone. Cutters are small to medium size ships designed for speed rather than for capacity. They tend to be single masted, which is set further back than on a sloop and with fore and aft rigging. They have two or more headsails and often a bowsprit. Both the ships were lost, the Alert in 1778 and the Rattlesnake in 1781.

From the 1770s Henry Ladd was in sole charge of the family shipyard and he had three sons who served as apprenticed shipwrights with the family firm. They were Henry junior (1755-1801) – Freeman in 1777, Luke (b1758) – Freeman in 1778 and Thomas (3) (1765-1806) – Freeman in 1786. Henry senior died in 1790 and the business passed to Henry and Luke. The Ladds’ were keen to pass on their skills and took on a large number of apprentice shipwrights. Mark Frost tells us that these included:

Stephen Peake (b circa 1763) apprenticed to Henry Ladd made Freeman in 1783

William Barritt (b circa 1768) apprenticed to Luke Ladd made Freeman in 1788

Joseph Pritchard (b circa 1769) apprenticed to Henry Ladd senior made Freeman in 1789.

John Bentley (b circa 1780) apprenticed to Henry Ladd made Freeman in 1790

Matthew Norris (b circa 1780) apprenticed to Henry and Luke Ladd made Freeman in 1790.

The Ladd shipyard was commissioned to build more Royal Navy ships including those designed by Sir John Williams. In 1771, the 28-gun Enterprise Class were the first frigates he designed but their sailing qualities did not match the equivalents designed by Sir Thomas Slade (1704-1771). Nevertheless, some 27 vessels were built to this design, more than to any other Sixth Rate design. These included five ships ordered in 1770 and 1771 and all brought into commission from the Ladd shipyard in 1775 and 1776. They were of 593tons with a crew of 200men and armament consisting of 24x9pounders and 4x3pounders. The Admiralty ordered a further 15ships of the same design, some from both Dover and Sandgate shipyards in 1880, including Ladds’.

Sir John Williams designed the Sprightly Class cutters – one-mast ships with a mainsail, two headsails and a bowsprit, a forerunner of modern day yachts. The prototype was the 150ton Sprightly I, built by the King shipyard in August 1777. She carried a crew of 60 men and had 10x3pounders and 12×1/2pounder swivels and shortly after 12 carronades x12pounders replaced the 3pounders. She was commissioned under Lieutenant William Hills but was lost, presumed foundered with all hands, in a storm off Guernsey on 23 December 1777.

The Navy replaced her the following year with Sprightly II, also built by the King shipyard. Costing £1,158 15shillings 5 pence and launched in August 1778, she was 150tons and was commissioned in September 1779 under Lieutenant Gabriel Bray for the Downs but paid off in 1780. Then, recommissioned in September that year and took part in the Battle of Dogger Bank on 5 August 1781 under Lieutenant Peter Rivett but was paid off again in May 1783. Recommissioned that month for Mounts Bay, west Cornwall but paid off in 1785. Recommissioned May 1786 for five years until she was again paid off. In 1792 under Lieutenant Richard Hawe and in March 1794 under Lieutenant Digby Dent and six months later under Lieutenant Robert Jump (-1801). She sailed for Jamaica in January 1799 but in February 1801 Sprightly II was captured by the 74 gun Le Dix Aout of Gateaume’s squadron in the Mediterranean and scuttled.

Another cutter ordered by the Royal Navy was the Expedition in February 1778 from the Ladd shipyard. Launched in August 1778, she cost £1,180 to build plus £1,348 fitting out and the ship’s bottom was coppered. The Royal Navy had introduced coppering of wooden ships’ bottoms as rivers were increasingly becoming infested with Gribble and Teredo worms. A mollusc that enters submerged timbers when it is very small and grows rapidly to about 4 to 6 inches in length and less than one-quarter inch in diameter. They riddle the interior of the wood until, without noticeable damage on the outside, an entire structure may suddenly collapse. All ships commissioned by the Royal Navy had to have 1milimetre or 0.04 inches thick copper sheathing covering the bottoms that gave the hulls a clean, wet surface that protected against the worms and, as a bonus, stopped the ships being fouled by weed.

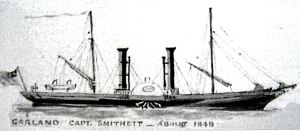

Commissioned in September 1778 for the Downs, the Expedition was paid off in 1783 but refitted May 1784 and paid off the following year. Recommissioned March 1786 was refitted in 1789-1790 as a Channel packet. With the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars, she was recommissioned May 1792 under the command of Lieutenant Grosvenor Winkworth for service in the North Sea. Followed in July 1793, under Lieutenant Bayntun Prideaux, for the Channel, then April 1796 Lieutenant George Raper (1769-1796). In 1802 she was under the command of Lieutenant Charles Boyes (died 1804) and decommissioned in conjunction with the signing of the Amiens Peace Treaty of that year (25 March 1802).

In August 1778 the King shipyard built and launched the 205ton brig Alert that was bought by the Royal Navy before completion. A brig was a two masted vessel with square sails on each mast for power, and fore-and-aft staysails for manoeuvrability along with jibs and spanker – similar to colliers of that time. She was launched in August and crewed by 80 men. The Alert carried 14x4pdrs, 12×1/2pdrs swivel guns and the cost including fitting and coppering cost £1,868 19shillings 10pence. Following the commissioning, the Alert was sailed under Commander James Vashon. That year she was seized by the American ‘rebel states’ and was used to set fire to two other British vessels carrying hay. Sir James Wallace (1731-1803) was the Captain of the 50-gun ship Experiment and he came to the rescue saving the Alert from being burnt too.

The Alert was in the Leeward Islands in February 1780 and at the Battle of Dogger Bank in August 1781. She was at the Battle of the Saintes 9-12 April 1782 off Dominica in the West Indies, following which she was paid off. The Battle of the Saintes, occurred due to the belief by the French that the American War of Independence could be ended successfully with the capture of Jamaica from the British. The British West Indies Fleet was under Admiral Sir George Brydges Rodney (1718-1792) and the French fleet, sailed from Fort Royal, Martinique under the Comte François Joseph Paul de Grasse (1722-1788). They first engaged off Dominica on 9 April, and then off the group of islets to the north called the Saints (Les Saintes) on the 12th. Rodney’s victory proved a counterbalance to the loss of the British colonies in America and allowed Britain to secure superiority over the French in the Caribbean in the 1783 Treaty of Versailles.

At Chatham, the Alert was then fitted out for the Channel packet service, which cost £617 10shillings 8d but in October 1783 was again laid up. Again fitted out at Chatham, this time for foreign service between April – July 1787, costing £625 1shillings 6pence. She was recommissioned in June 1787 under the command of Commodore George Burden and sailed for Jamaica. In 1791 she was again paid off and sold at Deptford for £235 in October 1792. The Alert was the only brig built for the Royal Navy to be disposed of prior to 1793.

Although the Dover shipyards were building vessels for the Royal Navy, they were also providing local shipowners and others with exceptionally fast ships that were being used as privateers and for smuggling. The shipbuilding yards, by this time, were along the beaches from Shakespeare Cliff to East Cliff and the number of privateers operating out of Dover during the War was in excess of 50. Most were built at Dover and shipbuilders and ancillary shipbuilding tradesmen operated many. For instance, Henry Ladd built and owned the 200ton British Hero with 16 carriage guns and captained by local John Wellard (1743-1817). He also built and owned, with others, the 45ton Charlotte and the 100ton cutter Job with Samuel Kempe and captained by Henry Pascall. She was put up for sale in in 1779 and described as ‘a prime sailor, exceedingly well founded.’

The King family built and owned the 129ton privateer Drake, and the three masted, 50 ton Surprize with 64x2lb carriage guns, 6swivels, 20 crew. Along with James Gravener, the King’s owned the 60ton Martha, a privateer with 8 swivel guns, 20crew and captained by Robert Steriker (1753-1830). In 1782 she took the Adventurer, a French privateer of Dunkirk and was sold in a sale at the King’s Head Tavern, Clarence Place next to the harbour. The 200ton Resolution was built by the King shipyard and owned by them along with John Osborne who was also her Captain. She was armed with 12x6lb carriage guns, 20 swivel guns and carried a crew of 60. She traded between Dover and Guernsey smuggling wines to London. Ropemaker John Goodwin owned the 260ton Bridgetown that carried 4 swivel guns and had a crew of 18. The 208ton Speedy, a three-masted brig designed by Sir John Williams, was built by a Dover shipbuilder carrying 14guns was launched in June 1781. She had a glittering career as a privateer as well as a Royal navy ship. While in that capacity and under the command of Thomas Cochrane (1775-1860), 10th Earl of Dundonald, Speedy was famous in capturing El Gamo, a Spanish treasure ship.

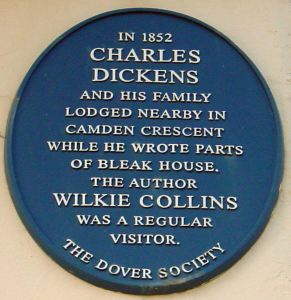

Smuggling was increasingly being organised by Dover businessmen with the government retaliating by increasing the number of Riding Officers. In 1778 the Dover’s Paving Commission was set up by Act of Parliament, its principal function was for town management including street lighting. Mayor, Matthew Kennett (1739-1818), of a ship owning family, took a leading part in framing the Act and the resulting document pleased the government. The Commission was made up of sixty-four named persons, including Matthew Kennett, and Jurats Christopher Gunman (1714-1781), James Hammond, John Latham, John Coleman, Thomas Bateman Lane (1746-1821), James Gunman (1747-1824) and Phineas Stringer (1730-1801). Nonetheless, Dover’s street lighting continued to be kept deliberately poor for as Charles Dickens (1812-1870), noted in his opening chapter of ‘The Tale of Two Cities,’ ‘… A little fishing was done in the port and a quantity of strolling about by night, and looking seaward, particularly at those times when the tide made and was near flood. Small tradesmen who did no business whatever, sometimes unaccountably realised large fortunes and it were remarkable that nobody in the neighbourhood could endure a lamplighter!’

The War raged on and the Royal Navy continued to be interested in purchasing Dover built ships. The 206 ton brig Lively, built by the King shipyard, was launched in June 1779. The cost, including fitting out and coppering, was £1,821 11shillings 9pence. The Royal Navy purchased her along with the 181ton Cockatrice, also built by the King shipyard and launched the following year. The 340ton Merlin was purchased from the King shipyard while still being built in 1780. A sloop, she was crewed by 125men and initially had 18x6pounder guns. A sloop was a one-masted vessel with a mainsail, one headsail and no bowsprit. The Royal Navy also purchased the 317ton Bulldog, built by another Dover shipbuilder while William Crow, William Pepper and Captain John Blake, independently, bought the 124ton Nile, which carried 14x6lb carriage guns. In 1799 she was described in a newspaper article as a beautiful new lugger fitted out in Dover and pierced for 18guns. The Nile had a successful career as a privateer as was the Swift I. She had 6 swivel guns and 30crew and was owned and captained by John Osborne in a consortium with London merchants William Richards and Joseph Graves. Osborne was also part of the King consortium that ran the Resolution.

In 1780 William Hedgecock (b1765), son of victualler Michael Hedgecock (d1769), joined the Pascall yards as an apprentice and some seventeen years later formed a partnership with John Pascall trading as Pascall and Hedgecock. The continual demand for Dover ships attracted even more shipbuilders to set up their own businesses on Dover beaches, including John Freeman (1759-1831). He was born in Folkestone and apprenticed to a Dover shipwright about 1776 becoming a Freeman in 1781. Soon after Freeman opened a shipyard at Harts Row off Beach Street, close to Archcliff Fort. He married Elizabeth Vincer (b1760), of a shipbuilding family, and his two eldest sons, John (1787-1843) and Thomas Vincer Freeman (b 1789), were apprenticed to the Freeman shipyard as shipwrights. The Royal Navy commissioned ships from the Freeman shipyard along with the other Dover shipyards.

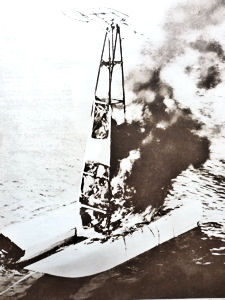

From the Ladd shipyard, the Royal Navy commissioned a prototype fireship/sloop, Tisiphone, the first of nine ships in the Tisiphone class, all of which were built on Dover beaches. The Tisiphone was launched in 1781 and the others were the 423ton Alecto launched 1781 and the 424ton Incendiary launched 1782, both built by Thomas King and each crewed by 55men. There was also the Comet (1783), Conflagration (1783), Megaera (1783), Pluto (1782), Spitfire (1782) and the Vulcan (1783). The design of these fireships was based on a French privateer fireship captured in 1745 and similar in many ways to a sloop of war. Indeed, fireships were often employed as sloops of war until they were used for the purpose they were built. The design of fireships differed from other ships in that they had a flush upper deck with the bulwarks carried forward along the waist and was pierced for gunports. When used as fireships they were filled with combustibles, set on fire then positioned to drift into an enemy fleet at anchor. Until they reached the chosen destination they were steered by a skeleton crew who escaped in the ship’s boat following impact with the enemy ship. An explosion ship or hellburner was a variation on the fireship, intended to cause damage by blowing up in proximity to enemy ships. As warships of this time were built of wood, caulked with tar and greased rope as well as carrying gunpowder, they were vulnerable to fire and therefore fireships were a major threat. Not only did fireships destroy enemy ships, they created panic and if the enemy were on the move, when a fireship was sent among them, it forced them to break formation.

In Greek mythology Tisiphone was the Avenger of Murder – one of the three Furies – and the Tisiphone fireship was ordered in June 1779 and launched in May 1781 at a cost £9,195 3s 9d to build, including fitting and coppering. The Tisiphone was laid up in March 1785 and underwent a small repair at Woolwich. In May 1790 she was recommissioned under Commodore, later Admiral, Charles Tyler (1760-1835) and in 1793, was under the command of Commander Thomas Byam Martin (1773-1854) later Admiral of the Fleet and took the 12-gun privateer L’Outrade March that year. Although built to be used as a fireship, the Tisiphone, along with the other Dover built fireships, had all the attributes of a Dover built ship, including built of the finest locally grown English oak, Quercus Robur. She was therefore deployed as part of the battle fleet while awaiting her destruction as a fireship. This virtue of the Dover built ships was credited with reducing the British fleet from the enormous size required in the American War of Independence, to a streamlined service geared toward protecting merchant trade and the British Empire during the Napoleonic Wars!

The Alecto was the first of the Tisiphone class fireship the King shipyard built for the Royal Navy costing £9,700.15shillings 1pence including fitting & coppering. After being paid up and laid up following the American War of Independence, the Alecto was recommissioned in 1798 and she also served as guardship at Lymington prior to he sale in 1802. Another of the Tisiphone class fireships built by the King shipyard was the Incendiary, launched 12 August 1782 costing £9,570.14.5d including fitting & coppering. Like both the Tisiphone and the Alecto she was not used for the job for which she was built and for the same reasons – she was of a superior craftmanship and built of Quercus Robur oak, which was ideal for shipbuilding as it did not burn easily! Instead the Incendiary was recommissioned in February 1793 and refitted at Sheerness. Eventually she was used as a fireship, along with the Majestic and Daedalus when they destroyed the storeship Suffren off Ushant, Brittany on 8 January 1797. With Suffren well alight and the other fireships ablaze the crewless Incendiary sailed out of the mayhem. A crew was despatched to deal with the smouldering ship but found that she had only suffered superficial damage! At a cost of £2,294, the Incendiary was refitted at Portsmouth but after a successful career particularly against French privateers, the 80-gun L’Indivisible of Count Honoré Ganteaume (1755-1818) captured her on 29 January 1801. This was in the Gulf of Cadiz, the southernmost point of mainland Portugal and recognising she was a fireship, her captors set her alight. The Incendiary refused to burn and her dignity throughout the ordeal was so awe-inspiring that it was suggested that she should be offered as a prize for diplomatic purposes. For whatever reason, a decision was made to scuttle her and the Incendiary gracefully sank to the bottom of the sea.

For quite sometime, some of Dover’s shipping companies had bought licences from the Post Office to operate the cross-Channel Packet industry. However, due to the danger from French privateers during the American War of Independence, they ceased this activity, sold their packet ships and invested in smaller, faster sloops, with relatively shallow draughts. These vessels enabled them to use the smaller Continental harbours for smuggling purposes. When peace returned, illegally importing contraband from France enabled them to maintain their lifestyles that they had acquired throughout the lucrative years of the American War. Although there was an increase in the number of Revenue men and cutters, smuggling became one of Dover’s major and most lucrative industries. Respectability was maintained with the reintroduction of the packet service, for which ships built in Dover were used. Four packet ships made the crossing every Wednesday and Saturday with mails for Calais and Ostend. As the Turnpiked Road to Folkestone from Dover, over the cliffs, was increasingly ‘dangerous from the falling cliffs,’ the present Folkestone Road through the Farthingloe Valley was built to replace this by the Turnpike Trust. The new road opened in 1783 and remained a turnpike until 1887. The abandoned old road to Folkestone, enabled more smuggling to take place along the cliffs in the area.

At this time, until the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars, the ships built in Dover for the packet, passage and smuggling industries included the 48ton Ant, 78ton Countess of Elgin, 56ton Dart, Defence, 49ton Dover, 66ton Duchess of Cumberland, Flora, Hardwick, Industry, Lady Casterleagh, Lady Jane James, Lark, Lord Duncan, 160ton cutter Nymph, Pitt, Poll, Prince Leopold, Prince of Wales, Prince William Henry, 71 ton Princess Augusta, the 96ton schooner Princess Charlotte, Sybil, Susanah and the 50ton Venus. As the old Folkestone Road was no longer the main road out of Dover, the shores along cliffs on that stretch of coast became ideal for landing contraband increasing the smuggling industry profits. The industry became so flagrant that there was a public outcry and investigations were undertaken. It was found that in Dover the game of eluding the revenue laws were played to perfection and the Admiralty Records show, that Customs Officers more than once complained of the obstruction they met from the towns folk. It was known that tea was the main item being smuggled at Dover at this time. By the middle of the eighteenth century 4million pounds of tea was consumed in the country but duty had only been paid on 800,000 pounds! It was believed that Dover packets were the main carriers of the contraband as the frigates were the town’s largest ships and therefore were more likely to be able to keep the tea dry. The town’s two largest shipowners, the respectable Fectors and Lathams owned the packets.

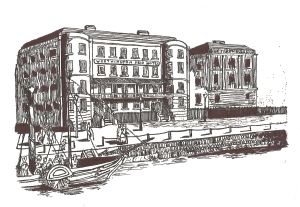

Dover custom house on Custom House quay built in 1666 and demolished March 1821 and replaced by a new Custom House built by John Minet Fector bank that year. Dover Museum

When the Revenue men wanted to go on board these packets, the ships had to tie up on Custom House Quay – approximately on the Snargate Street side of the present Granville Dock. A member of the shipowning family met the Revenue men and the senior officers were taken on board to participate in refreshments while the junior officers stayed on the quayside and kept watch. Throughout the inspection the crew were respectful and doing as requested by the Revenue officers. The inspections were undertaken without interference but nothing was ever found, nor did those on the quayside see anything amiss. Later that day, after the ship left Dover, the ship’s boats would be lowered below Hougham cliffs or at St Margaret’s Bay and smuggled caskets of tea would be taken ashore. Dover shipbuilders and associated trade had became ingenious in adapting the ships, its furniture etc. ensuring that tea was carried in the safest and dry conditions as possible!

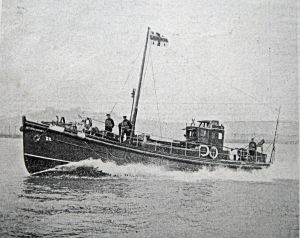

A representation of the English and Dutch fleets five minutes before action commenced in the Battle of Camperdown on 11 October 1797. The English fleet under the command of Admiral Adam Duncan (1731-1804) captured nine ships of the Line, two ships and took three Admirals. The battle is considered one of the most significant in British naval history. R is the Dover built frigate Circe carrying 28guns. Wikimedia

Albeit, following the end of the War of American Independence, those shipbuilders that had earned a good living from producing ships for the Royal Navy, were hit particularly hard as the Admiralty sold them off cheap and they ceased buying new vessels. Henry Ladd was declared bankrupt when proceedings were taken against him on 11 April 1785 by fellow shipbuilder, James Gravener. At the time, the Ladd yard was just finishing building Circe, an Enterprise Class frigate, which the Royal Navy had ordered in March 1782 but with the end of the war, had rescinded on the payment. This had cost the Ladd shipbuilding yard £6,117 including fitting out. The ship was laid up in the shipyard.

The French Revolution (1789-1799) started on 11 July 1789 and fearing what may happen to Britain, the government started to make preparations. The Admiralty increased its ship building policy and in September 1790, the Royal Navy recommissioned the Circe. They paid the money they owed for the ship and thus saved the Ladd shipyard. During the Napoleonic Wars the Circe was involved in the capture of the 14-gun L’Espiegle, off Ushant November 1793; took part in the Battle of Camperdown off the North Holland coast, 11 October 1797; the attack on Ostend on 18 May 1798. She also took the 12-gun Lijnx and 8-gun schooner Perseus at the mouth of the River Ems, northwestern Germany on 11 October 1799 but was wrecked on the Lemon and Ower Bank off Norfolk on 17 November 1803. In December 1797 the Circe was under the command of Captain Robert Winthrop (1764-1832) later Admiral of the Blue, who died at his residence in Dover on 10 May 1832.

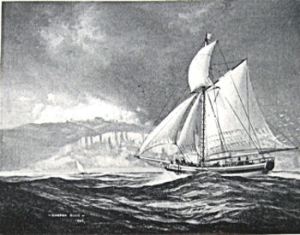

King George I 70ton sloop Cross-Channel Sailing Packet owned by the Fector family by Gordon Ellis. A model can be seen in the Museum. LS

There was also the King George II, built by the King shipyard for the Fector banking family, and whose master initially was Matthew King (1759-1832) and later George Bagster. The King George II was a 128-ton cutter with a hull designed to offer the minimum resistance in the water. This made her fast but not as fast as the Fector flagship, ex-Royal Navy 70ton sloop, King George I, also built by the King shipyard and remained the fastest ship on the cross Channel packet run. This was a feat that was not to be surpassed until the steam packets broke her record in the 1820s. A model of the King George I can be seen at Dover Museum but it was King George II packet ship, that was believed by the customs and others to be particularly heavily involved in smuggling. At this time, the average sum of duties collected by customs in Dover from 1788 to 1793 was only £14,269 per year and only amounted to a third of the salaries, wages and other outlays of the custom post in the town. On this subject Edward Hastard (1760-1855), in 1797, wrote that ‘so numerous are the contraband traders here whose success is chiefly owing to the blackness of the night; and at this time there is not a single light in the night throughout the whole town of Dover.’

A cutter, frigate and an Indiaman with other ships all of which are typical of the ships produced by the King shipyard. Wikimedia

By 1790 William King of the King shipbuilding business, was active in local politics. His first taste came in 1784, when he was appointed by Dover’s councillors as one the Commissioners to the Court of Requests, even though he was not a member of the Common Council. The Court of Requests dealt with small debts up to £5 owed to tradesmen and the Commissioners had to have real property of £30 to £500 in personnel wealth. Shortly after King was elected a councillor and in 1790 he was elevated to that of a Jurat – the inner sanctum of the Corporation. It also bestowed upon him the eligibility to being elected a Mayor, as he was in September 1798. By that time King was heavily involved in producing ships for the Royal Navy and in 1800 was actively involved in the erection of New Bridge, designed to help Dover to become a tourist resort. However, in 1807, it was taken as granted that he would be elected Mayor again but the proposal was fiercely contested by Thomas Mantell (1751–1831) the leader of the anti-smuggling lobby. Although King won, this was only by a small majority and not only did he not stand again, but the King shipyard in Dover closed and the firm moved to Upton (Upnor), on the Medway.

Another of Dover shipbuilding families was the influential Worthingtons. Their residences were at Maxton, nowadays a suburb of Dover at the west end of the Folkestone Road in Dover. The centre of their holdings was the Manor House at Maxton and about 1800, one of the members, had warehouses along Gardiner’s Lane, the only thoroughfare out of Dover going westwards. For this reason, the road was changed to Worthington Lane – now Worthington Street. One of the Royal Navy commanders during the Napoleonic Wars was Lieutenant Benjamin Worthington, whose home was the Maxton Manor House and following the end of the Napoleonic Wars he occupied his time projecting schemes for the improvement of Dover Harbour. Another member of the family, Benjamin Worthington, for many years kept the Ship Hotel on Custom House Quay and ran the Dover and London mail coaches.

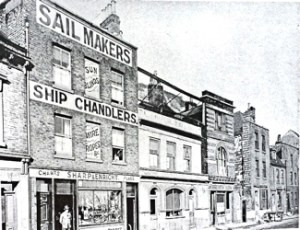

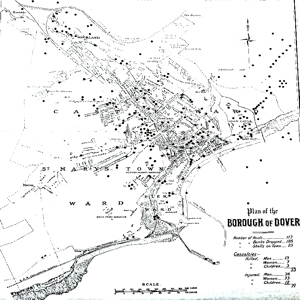

As the Napoleonic Wars were approaching, the Dover shipbuilders and affiliated occupations had so perfected their techniques that Dover built ships were refereed to as the ‘Pride of Europe’. At the time the main shipbuilders listed were: Thomas Allen, Cowley & Austin, T Finch, Gilbee and Farley, Benjamin Glandfield, James Gravener, Kemp and Johnson, Matthew Kennett, Thomas King, Luke Ladd, James Large, Pascall and Hedgecock. John Scott, Robert Taylor, S T Walker and Elias Worthington. The ropemakers were Peter Becker (1764-1842) & Richard Jell (1762-1847), Richard Witherden (d1800) and Stephen Witherden (1757-1826). Thomas Ismay (1747-1827) was a ship-chandler and also an ironmonger, blacksmith and brazier. Becker & Jell were sailmakers as well as shipbuilders, as was Edward Ladd, Ratcliff & Co and Nicholas Ladd Steriker (1767-1830). During the Napoleonic Wars a tax was introduced on sails and all sail cloth was stamped with its place of origin on each sheet when the tax had been paid. It was a serious offence to use sails, which had not been stamped.

On 1 February 1793, France declared war on Britain and the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) began.

The Dover Shipbuilders story Part 3 covers the Napoleonic Wars 1793 – 1815

Presented: 04 May 2018