In 1856, Charles Dickens (1812–1870) stayed at the Ship Hotel, on Custom House Quay, to work on Little Dorritt. However, due to concerns over domestic issues he spent most of his time taking long walks and talking to locals. These were recounted in Out of Season, published in Household Words. Some years ago, I undertook a piece of acclaimed academic research in relation to A Tale of Two Cities, Dickens’ twelfth novel, (Dickensian Summer 2002 pp 140-144). Dickens’ started working on the novel in March 1859 but I successfully showed that it was his 1856 stay in Dover that inspired many of the themes that he used.

The book is set at the time of the French Revolution (1789) and starts with a coach journey to Dover. Charles Dickens describes the town at that time and making an oblique reference to smuggling, ‘The little narrow crooked town of Dover is itself away from the beach, and ran its head into the chalk cliffs, like a marine ostrich. The beach was a desert of heaps of sea and stones tumbling wildly about, and the sea did what it liked, and what it liked was destruction. It thundered at the town and thundered at the cliffs, and brought the coast down madly … A little fishing was done in the port and a quantity of strolling about by night, and looking seaward, particularly at those times when the tide made and was near flood. Small tradesmen who did no business whatever, sometimes unaccountably realised large fortunes, and it was remarkable that nobody in the neighbourhood could endure a lamplighter!’

The key characters in the Tale of Two Cities not only have similar names to members of Dover’s Minet-Fector family, there is reason to believe that the main character, Charles Darnay, was based on one of Dover’s leading personalities at the time of the French Revolution (1789), John Minet Fector (1754-1821). A key player in the Dynasty of Dover, John was the son of Peter Fector (1723-1814), who came to Dover as a 16-year old from Rotterdam to do his apprenticeship in his uncle’s shipping business. His uncle was Isaac Minet, a wealthy Huguenot (French Protestant) merchant of Calais who managed to escape to England in 1685 at the time of religious persecutions in France.

Isaac Minet’s home and business was in Strond Street on the north side of the Bason, now Granville Dock, in the Pier District. Between Strond Street and the Western Heights was – and still is – Snargate Street and on the other side between Strond Street and the Bason, Custom House Quay. There, Isaac built ‘notable mansion’, named at Pier House, which fronted Strond Street and backed onto the Quay. Nearby was the Customs House that gave its name to the quay. Once Isaac was made a Freeman, his business flourished and by 1721, he owned four packet boats running regularly between Dover, Calais and Boulogne.

Isaac was a frail old man when Peter Fector came to Dover so he was put to work and train Isaac’s youngest son, William Minet (1703-1767) direction. William was an excellent teacher and by April 1743, Peter had become confident in all aspects of the company business and noting what new directions it might take. In charge of the Custom House next door was Kit Gunman (1714-1781), who had purchased the lucrative position and would boast of the excise taxes he imposed of which he received a percentage. Peter Fector observed that Dutch and French ships would use Madeira, a Portuguese island, as a clearing house for trade with the English American colonies, which seemed to him to be illegal.

Gunman explained that the English Navigation Acts were designed at keeping the English colonies dependent on the mother country. This should have meant that goods could only be transported in English ships or via England and this accounted for why the Dover custom house was so busy. However, the man with the power behind the Portuguese throne, the Marquis of Pombal (1640-1777) had, during his career, created a special relationship with England. Part of the agreements allowed him to turn Madeira into a clearing port under the English Navigation Acts, as the island was en-route to the America’s from mainland Europe. (See the Edward Randolph story). This, Peter was to bear in mind and later opened an office in Madeira.

It was about this time, circa 1740, that Isaac and William took the first step into the field of banking. Although the running of their own ships was the main function of the business, they were also shipping agents, importers, and exporters on their own behalf as well as for others. Isaac was already offering deposit facilities of hard cash to both mariners and traders for which he issued a receipt. Because of the number of transactions going through the books, these receipts started to be used as tender – or Bills of Exchange – which, particularly traders, were using to settle commercial transactions. The Bills of Exchange where then used by the purchaser of goods to buying another set of goods. Somewhere along the line one of the suppliers present the Bill of Exchange – that may have been used for several transactions – to the Minet establishment in exchange for cash. The deposited hard cash, in the meantime, was kept safe by the Minet’s who charged a low interest rate to the final person in the chain.

The Wars of the Austrian Succession (1740-1748) had been raging for four years before England, in March 1744, joined in. This brought the country into conflict with her old enemy, France and from April that year, Dover’s ship owners could buy Letters of Marque. These were effectively a licence issued by the government that allowed private citizens to seize goods of enemy ships as a prize for making war on them – in other words a legal form of piracy! Privateering, as it was called, was to provide the fortune of a number of Dover households including the Minet-Fector. Indeed Peter writes on 5 September that he expects to get a cut as a ship of company, the Eagle, had successfully captured a French ship!

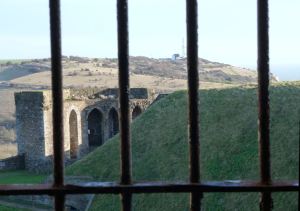

The French prisoners of war were housed in Dover Castle and it was Peter’s job to exchange the prisoners’ money into English currency to enable them to buy food etc. from the prison guards. Among the prisoners were French officers from affluent families who received greater sums from home. For these prisoners Peter recognising that they were vulnerable to theft offered to look after their hard currency and issued Bills of Exchange that they used to buy goods. The prison guards were happy with this and soon the Bills of Exchange became an unofficial form of currency.

Uncle Isaac and William along with Peter, quickly realised that the amount of hard cash that was being withdrawn from their depository, was only a small percentage of the full worth of their Bills of Exchange. Therefore, they could issue Bills of Exchange backed by either of the currencies when folk asked for loans and because there was not much call for the hard currency, the chances of having a run on that was low. When they took this step, Dover’s business community started to expand and modern High Street banking was born.

On 8 April 1745, Isaac Minet died and was buried at St Mary’s Church where a memorial can be seen near the south door. On 9 September, Peter paid £10 to become a Freeman by purchase and in 1746, bought one-third share in the Dover business. At Canterbury Cathedral on 13 July 1751 Peter married his half-cousin, Mary Minet (born 4 February 1728), against the wishes of her father. They had 5 children, Elizabeth (1752-1820), who married Charles Wellard; John Minet (1754-1821), more of whom below; Mary (1757-1814) who became Peter’s housekeeper on the death of her mother; James Peter (1759-1804) more of whom below and William (1764-1805) actor/ theatre manager.

Uncle William died on 18 January 1767 in London and his body was brought back to London for burial at St Mary’s Church and Peter increasingly took control of the extensive Dover business from other Minet family members. Back in 1753, Peter had been forced to resign from the office of Dover council Jurat, because he was not English by birth. This affected Peter so much that he became ruthless in all his transactions and refused to have anything to do with Dover’s established society except for business. Albeit, two of Peter’s sons, John (b1754) and James (b1759) were already part of the business, John working to take over the shipping side and James learning the basics of banking.

The American Colonies declared their independence from England on 4 July 1776. In the same year a recent emigrant Thomas (Tom) Paine, whom it is locally believed to have come from Sandwich, published the pamphlet ‘Common Sense.’ Aimed at those loyal to the Crown, he said that they were ‘… with a heart of a coward and the spirit of a sycophant,’ and two years later, on 17 July 1778, France declared war on Britain in support of the Colonists. Dover’s defences were put in charge of Captain Thomas Hyde Page (1746-1821) and in 1781, the Board of Ordnance bought two parcels of land on Western Heights, totalling 33 acres. Page, organised the building of fortified batteries, on this land, for which he was knighted. By the time peace returned the works on Western Height incorporated a self-contained redoubt fort at the eastern end of the hill and a Citadel on the west, with entrenchments between – this was the start of a major permanent new fortress on the Western Heights.

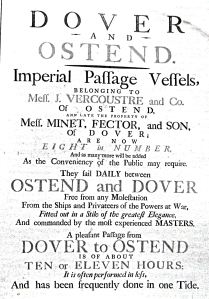

During the American War of Independence 1776-1781 the Fectors sold some of their ships to Flanagan Vercoustre of Ostend. Dover Museum

Initially, the War took its toll on the Fector business and Peter was obliged to sell some of his ships to Flanagan Vercoustre of Ostend. The Fectors still managed them and had Letters of Protection. However, French privateers took little notice and the Dover packets were in danger of ceasing. The Fectors and other packet owners started to use small but fast boats with shallow draughts and used ‘safe’ Continental natural harbours. Their main source of income was smuggling. From these revenues the Fectors started to buy their ships back and successfully sought Letters of Marque. This enabled the ships to carry weapons and as records show, the Dutton, an East Indianman running out of Dover made £30,000 in profits from only three privateering voyages at that time.

Nonetheless, the Fectors, and it was believed the eldest son John, was either involved or turning a blind eye to smuggling when their boats and ships were involved. Soon the smuggling became so flagrant that there was a public outcry and investigations were undertaken. It was found that in Dover the game of eluding the revenue laws were played to perfection and with even more zest in the West Country. Admiralty records show that Customs Officers more than once complained of the obstruction they met with when the Revenue men went on board Dover packets and passage ships to carry out routine examination. By the end of the War four Dover packets operated, making the crossing every Wednesday and Saturday with mails for Calais and Ostend and belonged to either the Fectors or the Lathams, Dover’s other banking family.

By this time, Dover was in the state described by Dickens’ in Tale of Two Cities, cited above. In 1778 the Dover Local Government Act created the Dover Paving Commission in order to rectify matters. The Act was renewed in 1810 and three times after, the last time in 1835. The members included members of Dover’s old established elite and a number of new ‘monied’ personnel but not the Fectors. Although the Commission instituted a number of reforms it was noticeable that the lighting of the streets was to remain deficient compared to other towns and cities. Historian, Edward Hasted, wrote in 1797, that ‘so numerous are the contraband traders here whose success is chiefly owing to the blackness of the night; and at this time there is not a single light in the night throughout the whole town of Dover.’ Brandy, wine and tea were the main commodities smuggled.

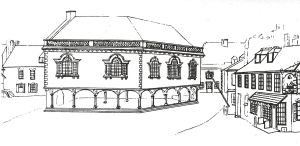

Old Customs House built 1666 demolished March 1821 replaced by John Minet Fector Bank in 1821. Dover Museum

This was not new, John Wesley (1703–1791), the founder of Methodism first visited Dover in 1760 and expressed concern about the prevalence of smuggling, denouncing it by saying, ‘every smuggler is a thief-general who picks the pockets both of the king and all his fellow subjects. He wrongs them all.’ While William Arnold, the Revenue Collector for Cowes, having been to Dover, wrote in 1784, ‘These vessels frequently convoy over the other smaller ones. They keep off until towards night, when they run and land their cargoes at places where gangs of smugglers sometimes to the number of 200-300 meet them. Goods are often landed and (are) of large casks, which have been unshipped from the seafront, the importing vessels. As soon as seen by a Revenue cruiser, they drop the boat astern, which immediately rows off while the commander of the Revenue Cutter is pursing the vessel he supposes to be loaded …’

The following year, 1785, the people of Dover witnessed, with great excitement, the flight from Dover’s Castle Hill to France of Dr John Jeffries from Massachusetts and M. Jean Pierre Blanchard, in a hot air balloon. Mail coaches between Dover and London were introduced in 1786, which increased the number of passengers crossing the Channel to the Continent. In the autumn of that year, just as the crops were being brought in, East Kent suffered the ravages of unprecedented storms. Many of those who normally worked on farms came into Dover to look for work around the harbour or on ships. Both the Fectors and Lathams, Dover’s other maritime banking family, were sending out coastal vessels to bring back supplies of vegetables and cereals.

In 1783, the firm became Fector & Minet with John in charge. ‘A Gentleman’ on a ‘Tour thro’ the Whole Island of Great Britain’, in 1792, wrote, ‘… The Packets for France go off from here, in time of Peace, as also those for Ostend, with Mails for Flanders; and all those Ships which carry Freights from New York to Holland and from Virginia to Holland, come generally hither, and unlade their Goods, enter them with the Custom-house Officers, pay the Duties, then enter them again by certificate, reload them and draw back the Duty by Debenture, and so they go away for Holland …’ John was one of the main shipping agents to many famous London merchants and also looked after the interests of the East India Company.’

John married Anne Wortley Montague Laurie (1769-1848) of Glenairn, Dumfries, in 1794. She was the daughter of General Sir Robert Laurie, member of Parliament for the county of Dumfries . They had four children, Anne Judith born 1799, Charlotte Mary born 1801, Caroline born 1804 and John Minet junior born 28 March 1812. James married Frances Lane, daughter of Thomas Bateman Lane in November 1783 and had five children, three of which survive to adulthood. They were, Peter Lane born 1787, Mary born 1791 and Emma born 1792.

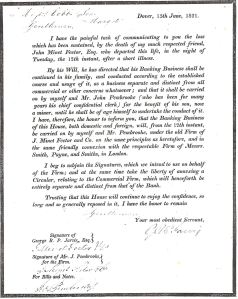

Minet Fector Bank draft for £20.3s payable to W & E Allen 24.10.1801. Reproduced by kind permission of The Royal Bank of Scotland Group © 2013

By the outbreak of the Napoleonic Wars (1793-1815) John was not only well respected he had that extra quality of commanding loyalty from his workers. This loyalty was well rewarded as was shown when the captain of the Prince of Wales, one of their cross-Channel packets, was found carrying a substantial amount of contraband. John stood bail for a ‘considerable sum’ and although the smuggled cargo was impounded, no charges were brought. Nonetheless, there was concern over John’s alleged smuggling activities particularly by Thomas Mantell. Following the French Revolution on 11 July 1789, John’s fleet of ships, sometimes with John at the helm, were known to be crossing the Channel far more often than warranted by the number of passengers or goods carried. During the year of his Mayoralty, in 1795, Thomas Mantell led a crusade against smuggling with his sights set on John.

Officially, during the Napoleonic Wars, Calais and other Channel port were no longer open to English ships but because the Fector bank held a large percentage of the Vercoustre company based in Ostend, their ships sailed under the neutral Belgian flag and were immune from attack. In fact, their advertisement asserted that they sailed ‘free from moslestation from ships and privateers of the Powers at War’. Nonetheless, the Napoleonic Wars put a great deal of strain on the British economy. Between 1793 and 1796, the government’s deficit abroad amounted to £36,439,269 with excise and customs duties its main source of revenue. This was of a similar magnitude to the deficit that had started the chain of events culminating in the French Revolution.

Matters came to a head in February 1797 when the coins and bullion held by the Bank of England against liabilities such as its banknotes, had fallen so low that the Bank Restriction Act was passed which meant that bank notes could no longer be exchanged for gold. On 5 March 1798 a man was about to be arrested at a fisherman’s house, in Folkestone, escaped but was later apprehended at Rochester. He left behind him three mahogany boxes in one of which were some letters. The captain of a Dover vessel was arrested and he acknowledge that he had accepted a large bribe from the man who wanted a passage to France. The fisherman was to take the man and the boxes to the vessel.

In April 1799, a warrant was issued for John’s arrest but before it was invoked, he had disappeared and the people of Dover closed ranks around him although there was a substantial reward on offer. John was accused of ‘aiding the enemy’ by smuggling gold to France in exchange for wine and brandy. The hearing was held without John and the evidence against him was overwhelming and included papers that the man in Folkestone had left behind. To everyone’s surprise John was suddenly cleared! (see Peter Fector – the story behind the Town’s treasure and the Country’s banking system)

Hardings Brewery 1862 that was previously Lower Buckland Paper Mill, painted James A Tucker c 1910. Dover Museum

Part of the Bank Restriction Act enabled country banks, such as the Fectors, to print promissory notes. James had virtually taken over from Peter the running of this side of the business at local level, particularly the mills. The three-four mile long, River Dour supported seven paper mills and six flourmills. In around 1780, William Phipps purchased the River paper mill using a loan from the Fector bank. Two years later Phipps was declared bankrupt and the mill reverted to Fectors with Phipps running it. Phipps quickly recovered his financial position and leased the mill from the bank. In 1800 he paid £2,000 through Israel Claringbould ‘to Peter and James Fector’ to repurchase it. In 1795, Phipps purchased the lower Buckland Paper Mill using loans from both Fector and Latham banks.

For his part, Peter concentrated on lending money to the wealthier clients with large estates around Dover and by their default, acquired a number of them. He purchased Kearsney Manor in 1790 and gave it to his son John. Peter had, in 1762, built a fine mansion Eythorne House, a village of the same name north east of Dover that had views across the Channel to Boulogne. There he had lived with his beloved wife, Mary and adored family. Mary Fector died on 21 October 1794 and was buried at Eythorne.

Although General Napoleon Bonaparte, seizing power at the end of 1799, caused consternation over the possible threat of invasion in Dover, the panic soon subsided. It was estimated that 10,000 troops were brought into the town to meet the invasion, but when it did not materialise most were given their marching orders. The militia followed the troops, but even they only stayed a short time. By the time the town and country were celebrating the two Acts of Union between Great Britain and Ireland on 1 August 1800, it was reported that only the local Volunteers and the Essex militia were quartered in Dover.

During the American War of Independence, Thomas Hyde Page, with the backing of John Latham, had set up the Dover Volunteers Association, the forerunners of the war time Home Guard and the present day Territorial Army. In 1798, eight companies had been re-formed by the decree of the Mayor, William Knocker, who also was appointed a captain. It was expected the William Pitt (1759-1806), Prime Minister and Lord Warden, would welcome the move but in 1803 he stated that they should, ‘never be sent out of the country except in case of actual invasion.‘ The main role of the Volunteers was that of signallers, ‘being stationed at different places along the coast to transmit to the others inland the news of the approach, if it should ever come, of the French fleet.’ However, Thomas Pattenden (1748-1819) wrote in his diary of the time, that volunteers paraded in their scarlet uniforms on the Ropewalk (now Camden Crescent) and then marched with William Pitt at their head to Maison Dieu Fields (now the Dour Street area). Pattenden described the defences that were erected in and around Dover to counter a possible invasion and details of the troops that embarked from the harbour.

As a reaction against the French blockading the port of Dover, the ‘Corps of Sea Fencibles for the Defence of the Coast of England against Invasion’, was formed. This included Dover’s two shipping magnets, John Fector and John Latham whose businesses were suffering because of the blockade. The corps was made up of seafaring men resident in Dover and other ports. Their duties were to gain intelligence and to offer greater security to coast-trading vessels.

On 22 July 1801, soldiers from the Castle reported that on the hills around Boulogne, they could see Napoleon’s army getting ready for invasion and in the harbour ships were being prepared to bring an army across the Channel. Within five days the British fleet, under the command of Horatio Nelson (1758-1805) assembled in the Downs off Deal. At 22.30hrs on the night of 15 August a fleet of ‘8 flat boats 8inch howitzers with a Lieutenant in each and 14 men and artillerymen … and 6 flats with 24 pounder carronades with a Lieutenant in each, seamen and 8 marines … under the command of four captains,’ crept into Boulogne harbour. Unfortunately, the boats did not arrive together and the first ones roused the French. They quickly took to their boats and the British flotilla was defeated. Of the men who set out 44 were killed and 128 were wounded.

With great relief in Dover, by October 1801, moves were being made to sign a peace treaty between Britain and France. This resulted in the Peace Treaty of Amiens of 27 March 1802 and that evening the Mayor George Stringer organised a grand ball at his home, Castle Hill House. Neither John Minet nor John Latham were convinced that peace would last for although the blockade of Dover had been lifted, the terms of the Treaty meant that the French could exclude the British from trading with ports that had French ties.

The Dover garrison was reduced from 10,000 men to just a few hundred and local trade almost died. Meanwhile the long term problem of the shingle bar was making the harbour difficult to enter. In an effort to combat this, the Harbour Board invited engineers John Rennie and Ralph Walker to suggest how improvements could be made. Their report was published on 8 December 1802 advising that the south pier be lengthened and contoured at its tip to ‘shoot the pebbles past the mouth of the harbour.’ The cost of undertaking was estimated at £54,000 and was therefore shelved.

As Fectors and Lathams expected, the Amiens Peace Treaty was not to last. At the end of March 1803, Napoleon Bonaparte announced that Britain had violated the Treaty. He subsequently occupied Switzerland and closed the Dutch Ports to British trade. On 17 May, Britain declared war on France and the government remobilised the Navy and reintroduced the Letters of Marque. Through the Army Reserve Act, they encouraged the enlistment of thousands of volunteers and re-introduced Income Tax that had been set up and abolished the year before. In Dover, Lady Hester Stanhope, (1776-1839) acting as deputy of the Lord Warden, her uncle William Pitt, equipped his volunteer regiment – the Cinque Ports Fencibles. Most Dovorians enrolled including both John and James Fector. Dover’s diarist, Thomas Pattenden recorded that the volunteers paraded in their scarlet uniforms on the Ropewalk and then marched with William Pitt at their head to Maison Dieu Fields.

Lady Stanhope wrote, ‘We took a (French) vessel the other day – loaded with gin – to keep up their spirits; another with abominable bread and vast quantity of peas and beans, which the soldiers eat. One of the boats had an extremely large chest of medicine, probably for about half the flotilla, their guns are ill-mounted and cannot be used with the same advantage as our fine pieces of ordnance. Bonaparte was to be at Boulogne a few days ago, our officers patrolled all night with the men, which was pleasant. I have my orders how to act in case of real alarm in Mr Pitt’s absence.’ (14 January 1804)

Some of the cross-Channel packet boats were fitted out as fighting ships and it is recorded that the Minerva, under the command of Lord Proby was used to gather pressed men. The Press gangs were made up of officers and men from the ship, who would go into taverns or even enter homes uninvited, and press any male they found into public service. These men, often not mariners, were then taken to join the fleet as sailors.

War meant an influx of about 20,000 soldiers into Dover and an impressive new orders for ships – sailing ships built in Dover already had the reputation of being the ‘Pride of Europe’. On 18 May 1804, Napoleon declared himself Emperor and the fear of invasion was very real. By 9 August, more than 100,000 seasoned French troops were on the hills outside Boulogne, while in the harbour there were 2,000 landing craft at the ready. The Volunteers set up a chain of semaphores from Dover to London, so messages could be passed to George III (1760-1820) should the invasion force arrive. Queen Charlotte (1744-1818) had been sent to Worcester with the Crown jewels for safety.

A massive defence programme was started on Western Heights, including the:

Citadel – The centre of the defences, this was built between 1804 and 1815, and completed in 1853-5 – during the next Napoleonic threat.

Drop Redoubt Fort – the second major defence. A sunken fortress of considerable strength, from which soldiers were able to fire in all directions, it was built between 1804 and 1808.

Barracks – These were located in the dip, near the cliff edge above Snargate Street. They provided accommodation for 59 officers, 1,300 NCO’s and privates plus eight horses. They were renowned for their light and airy situation and were used in times of war up until the end of World War II.

Military Hospital – This was built near Archcliffe Gate and had beds for 180 soldiers.

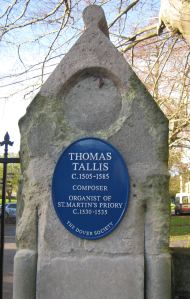

St Martin’s Battery, a 3-gun emplacement, and commanding unrivalled views of the harbour and town. It was named after the Patron Saint of Dover, St Martin.

Running between all these locations was, and remains, a series of deep dry moats, which were dug straight out of the chalk and lined with brick or flint.

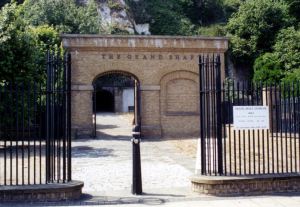

To get them men from the barracks to the harbour the Grand Shaft triple stairway was built. The total cost of the defences on Western Heights was £236,305 17s 2d.

Across the valley, at the Castle, the Mote Bulwark and the Guilford Shaft were built to link the Castle with the shore.

The Casemate Barracks were extended from just above Cannons Gate.

Along what are now Townwall Street and Woolcomber Street a defensive canal was dug – all traces of which have now gone.

The Cinque Ports Volunteers, for the most part, manned the defence of the coast and at St Margaret’s Bay, a wall that formed part of the defences can still be seen.

Ship and military building together with victualling meant that local trade boomed in the town as never before. Much of the timber for shipbuilding came from the forests around Lyminge, Elham and Lydden. The bricks were initially brought in by sea from Ipswich but at a cost of £3.12s 6d per thousand this galvanised Dovorians into manufacturing them. The first recorded brickfield was at Dodd’s Lane, off Crabble Hill and was founded in 1808.

The war also brought prosperity to Dover’s corn mills as they supplied the troops billeted in the town and naval ships in the harbour. At about this time the Maison Dieu was used as a massive bake house. The Royal Navy, in 1792, built Stembrook mill, south of what are now Pencester Gardens and as the demand for flour grew, the mill was rebuilt and enlarged in 1799 and again in 1813. To meet the demand, Thomas Horne (d 1807) rebuilt the Town Mill in 1802 and ensured that his corn mill at Charlton was in full swing. The Pilcher family rebuilt Crabble corn mill we see today in 1812 using loans from the Fector bank. They also rebuilt Temple Ewell and Kearsney Court mills.

Privateering brought considerable rewards and both the banking families were involved along with other Dover ship owners. Privateering ships were allowed to carry weapons – usually twelve or fifteen-pound cannonades – which they used to capture ships as well as to defend themselves. At the end of 1809 John Fector’s cargo ship, Mary, on her way home from America, was lost after being challenged by a French privateer. A contemporary account states that these conflicts usually took place late in the evening and provided entertainment for the locals, ‘It was curious on these occasions, to see men, women and children, running in multitudes, and as eager to witness these conflicts, as they would have been to view some harmless amusement. None seemed conscious of fear; but the field pieces, firing unexpectedly before the crowd, would sometimes cause them to scamper behind buildings.’

James Fector died on 9 January 1804 he was 45 years old and had played a large part in securing the family fortunes, particularly through banking and real estate. Following James’s death, John took over full control of the family business and the following year he was elected a Jurat of Dover (senior councilman) and High Sheriff of Kent. The latter was introduced in the 11th century and until Tudor times the Sheriff was the Sovereign’s sole representative in the County. By the early 19th century, the main role was to administer justice at the Maidstone – County assizes.

On the Continent, Napoleon was winning victory after victory. In March 1805, having seized Italy, he proclaimed himself King and on 9 August, another attempt was made to invade England from Boulogne. In Dover soldiers, both regulars and volunteers, stood to Arms for four nights and in the following weeks twenty-four and twelve-pound guns were landed at Dover to arm the Martello Towers that were being built along the coast from Folkestone to Lydd. In the Channel the British fleet, that included a number of Dover ships, was again under the command of Vice-Admiral Lord Nelson. While preparing for his attack Nelson, along with Lady Hamilton, stayed at John’s country residence, Updown House, near Ham to the east of Dover. Nelson led the offensive that prevented the invasion and the thwarted Napoleon turned his attention east where he routed the Russians and Austrians at Austerlitz on 2 December.

The British fleet was at Cape Trafalgar, off the southern coast of Spain, by 21 October 1805. That day, Nelson’s fleet won a crushing victory over the combined French and Spanish fleets. During the Battle, the Vice-Admiral was mortally wounded and his body was brought back to England for burial. His ship, the Victory, arrived off the South Foreland on 16 December and came into Dover as a gale was blowing. She left on the 19th for Chatham with Edward Sherlock, a Dover pilot, at the helm.

Following the death of William Pitt, on 30 January 1806, Robert Banks Jenkinson, the Earl of Liverpool, was appointed the Lord Warden (1806- 1828). A year later the ‘Case of Dover Harbour’ was presented to government in an attempt to extend the Tonnage Dues Act (Passing Tolls) that were about to expire. In 1723, Dover lost 66% of the Passing Tolls, revenue earned from ships traversing the Dover Strait to Rye. The argument put forward by Lord Liverpool was that Harbour Commission had a debt of £9,000 and the south-pier head needed rebuilding, the cost of which was estimated at £25,000. Following the submission Parliament agreed not only to extend the Act for another period, but also to take the right of tonnage dues away from Rye, on the grounds they had failed to construct a useful harbour. The final report stated that the dues were to be levied on all vessels from twenty to three hundred tons, passing from, to, or by Dover. Vessels laden with coal paid one penny the chaldron (approximately 28 cwt, 3,136lb or 422 kg) the same for every ton of grindstone, Portland and Purbeck stone.

James Moon was appointed harbour master and engineer and his first task was to deal with the enduring problems of the shingle bar across the harbour entrance and the south-pier. On 21 April 1811, he presented his report in which he said the south-pier head was in a dangerous state and suggested rebuilding it in a similar manner to the north-pier. Within the new pier-head, Captain Moon suggested, there should be a canal to direct water through three apertures onto the shingle bar to disperse it. He also recommended the building of a dry dock between ‘the boom-house and the houses in the King’s Head Street.’ (Now Clarence Place). He estimated that the work would cost £20,000 not including the dry dock but when digging began, flooding made it impracticable to proceed. Moon made further recommendations that were costly, put in place, but were not very successful.

The French prisoners of war, on arrival were taken to the town’s gaol before being moved up to the Castle. In 1808 Thomas Pattenden recorded, three escaped by boat, but they were pursued and recaptured in the Channel despite thick fog. The following year Thomas Mantell was again elected Mayor and his reputation against smuggling reached London where he was knighted, to set an example to others. As a gesture of goodwill John Minet Fector heavily contributed to the cost of a new larger Customs House along Customs House Quay requiring five houses to be demolished.

During 1811, the attack on Dover ships from French privateers increased. On 13 January John Fector’s ship, Cumberland, was set upon by four privateers off Folkestone on her way home from Quebec. During the confrontation, the French boarded her three times, but the Cumberland’s crew managed to fight them off. The fracas finished when the Cumberland, firing a number of rounds, disabled at least one of the French vessels. On arriving in Dover the captain reported that the Cumberland had lost one man and that the mate was injured but they had taken three French prisoners. It is also reported that during the encounter, the crew of the Cumberland had killed sixty French privateers but this was never substantiated.

Because of the continued shortage of soldiers, Parliament voted to revive the militia including that of the Cinque Ports. This was done at the expense of disbanding the Volunteers, who were then expected to join the regulars and go abroad. The men of the new Cinque Ports Militia were instructed to assemble in Dover in July 1811 but the women of the town, already fed up due to the lack of men to work in industry and agriculture, rioted. What actually triggered off the riot is difficult to ascertain, but the Corps was going through their marching drill in the Market Square when the women attacked them! Apparently, the soldiers ‘took to their heels and fled’! In consequence, the militia were ordered to Walmer where they continued their training and then were sent to join the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) on the Continent.

Following the abdication of Napoleon on 6 April 1814, a Peace Treaty was signed and once again, there were celebrations in Dover. On Saturday 23 April Louis XVIII (1814-15 & 1815-24), arrived at Archcliffe Fort on the Jason. He was on his way to being restored to the throne of France after 21 years in exile. The French King was received by a guard of honour headed by Mayor John Walker and after being welcomed by the Lords of the Admiralty he went to the Fector mansion on St James Street. At 19.00hrs that evening, along with John Fector and his wife Anne, the French monarch was joined by the Prince Regent (1811-1820) – later George VI on his yacht for a sumptuous meal. The Prince Regent also spent the night at the Fector residence and the next day, they all breakfasted on the Jason.

Not long after, on 8 August, Caroline of Brunswick (1768-1821), the estranged wife of the Prince Regent, stayed at the Fector house before crossing to the Continent. Caroline was a friend of the family and the Fector’s had named their third daughter after her. That summer, Emperor Alexander of Russia (1801-1825) had also stayed with John and his family and it was recorded that a considerable number of previously exiled French aristocrats stayed at either St James Street or Pier House at that time. One can only speculate how many of these people, or their parents, had crossed the Channel in John’s ships to safety 21 years before.

On 18 January 1815 Lady Hamilton, the mistress of Lord Nelson, died in Calais destitute, where she was buried. She had fled to France at the cessation of hostilities to escape from her creditors. On his death, it was said the Lord Nelson had bequeathed her care to the nation and a subscription was set up to bring Lady Hamilton’s body back to England. John made his prize ship, the King George, available for the task. At about this time Napoleon escaped from Elba and quickly reassembled his Grand Army. Determined to regain his supremacy Napoleon launched his army into battle and Dover became a hive of activity as the town was swarming with troops waiting to embark for Belgium.

During the morning of 18 June 1815, Napoleon and Wellington faced each other on the battlefield at Waterloo. Napoleon attacked while Wellington held his army in ‘battle squares’, waiting for his Prussians allies. Wave after wave of French attacked the British and Wellington was heard to say, ‘hard pounding gentlemen’. Eventually the Prussians arrived and the French broke ranks and were crushed. The battle was one of the bloodiest in history and lasted nine hours. 200,000 infantry, cavalry and gunners took part of which more than 13,000 were killed and 35,000 wounded.

After the Battle of Waterloo, approximately a quarter of a million soldiers and sailors, many of them maimed, returned home and were faced with unemployment and destitution. Crops had been poor and although Corn Laws had been instituted in an effort to curtail imports and protect the price of home produced goods; the Laws only served to make matters worse. Income Tax had been abolished but was replaced by taxes on staple commodities such as candles, paper and soap as well as luxury items such as sugar, beer and tobacco. In addition the Poor Law relief rates had been drastically cut, which meant the starvation was rife.

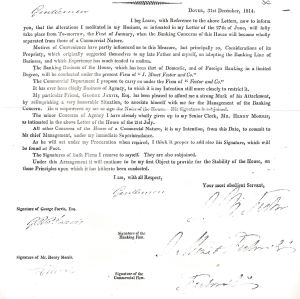

Peter Fector had died and was buried at Eythorne on 9 February 1814. In his Will, he left the Corporation of Dover three chests of silver plate for the town and in August that year, John presented the treasure to the Mayor, Henshaw Latham. In return a portrait of Peter Fector was hung in the Town Hall – it is now in the Stone Hall of the Maison Dieu. On 31 December John Minet Fector separated his business with the Banking side – J Minet Fector & Co – run by John’s old friend and lover, George Jarvis. John remained in control of the commercial/shipping side except for the minor concerns and these came under the management of his senior clerk, Henry Morris.

John and George had become friends about 1806, when George had been the acting Brigadier Major of his regiment in Dover. On the occasions when George was away on campaigns, John took responsibility for George’s wife, Philadelphia and their children. It was while he was on a campaign in Holland that George contracted Walcheren fever and returned to Dover a dying man. John looked after George’s care and it was during this time that their friendship became intimate. George resigned his commission to work for John.

For John the war had been exceedingly profitable but following the death of his sister Mary, who had managed all the country estates, he closed Updown House, Pier House and his parent’s home at Eythorne. He kept Kearsney Manor for entertainment purposes and the St James’ Street mansion as a town house. Nonetheless, he was seen as Dover’s Godfather and in 1818 was asked if he would stand as one of Dover’s representatives in Parliament, but declined. Instead, John decided to take his own and James’s family on an extended tour around Europe. He left the whole of his business in the charge of George Jarvis.

Following the Wars, the government decided to take a hard line against smuggling and in 1816, the Coastal Blockade was established. The Admiralty frigates, Ganymede, Ramillies, and Severn, were put under the command of Captain McCulloch, who proceeded to wage war on smugglers. All ships were watched, followed and frequently boarded. If any contraband was found, both the men and vessel were seized. Initially the Blockade covered the area between the North and South Forelands, but soon it was extended all round the coast from Sheerness to Beachy Head. By 1824, 2,784 men were employed and in 1824 the Blockade was extended to Chichester.

In Dover, the economic depression was biting and the Coastal Blockade made unorganised smuggling almost impossible. Then on 14 October 1820 John Minet Fector, Dover’s Godfather, returned home and it was reported that, ‘The pier heads were crowded by multitudes of people, who testified their grateful feelings by reiterated shouts of joy.’ His eldest daughter, Anne Judith Laurie Fector, had met and planned to married Henry Pringle Bruyere, a French Canadian sea captain, whose family had once lived at Archliffe Fort. Although against the engagement, John announced that ‘a splendid ball was to be given to all the beauty and fashion of the town and neighbourhood.’

John soon realised that the town was in a desperate state and that a ball was not expedient so he changed the celebration to an ‘At Home’. This was held on 27 October 1820 and according to contemporary accounts ‘nearly the whole male population of Dover, above the age of 21, consisting of 2,300 persons, were entertained at the Assembly rooms, in celebration of the return of Mrs Fector and her family to England.’ The day started with a peal bells from St Mary’s and St James’ churches and the male population were divided into five groups and given admission cards that allowed admission at 11.00hrs or 13.00hrs, 16.00hrs, 18.00hrs or 20.00hrs.

That morning ‘Barons and several other joints of beef were placed on a cart, drawn by 6 horses with riders in scarlet liveries.’ The cart was taken from John’s mansion to the Assembly Rooms at the corner of Snargate street and New Bridge. This was preceded by a band of musicians, and followed by a long procession of people. Flags, ensigns and banners decorated with laurel, adorned the Assembly Rooms and John’s elevated seat was surmounted with an arch, around which was inscribed, in large letters, ‘British Hospitality’. There were three transparencies surmounted by a large Union Jack on which was written: ‘The House of Fector, so honourable to the town of Dover; may it flourish for ages and perpetuate its high character for probity, liberality and benevolence. Health and long life to John Minet Fector, esquire, the munificent entertainer of crowned heads, and liberal benefactor and kind friend to his townsmen.’

John, with George by his side, interviewed every man and afterward, in a speech to the assemble throng, made it clear that smuggling was no longer an option. Instead, he said, he would boosted the employment prospects of the town’s men by building on part of the 11,000 acre Kearsney Manor estate a new mansion in the ‘in style of an Abbey.’ The mansion was for his only son, John, and the building programme was to start straight away. It was known from the outset as Kearsney Abbey. He also announced the building of an improved bank on the site of the now derelict old Customs House and make low costing credit available to all local businesses that needed it.

John Minet Fector was never to see the town boom again or Kearsney Abbey completed. He suddenly died on 12 June 1821 at Kearsney Manor, he was 67-years old. The town was shocked and grief stricken. The funeral route from Kearsney Abbey to St James churchyard, where a mausoleum was later constructed, was lined by ever man, woman and child in the district. John always looked after the town and the people had looked after John when he was in trouble.

Dynasty of Dover part Vi Fector – Jarvis gives as ccount of the next part of the story of modern Dover.

- Published:

- Dickensian Summer 2002 pp 140-144 (Basis)

Lorraine A.M Sencicle: Banking on Dover (Extracts)