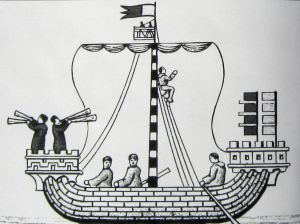

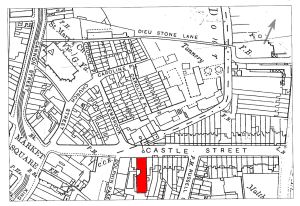

Town Station next to the beach. 1890 map

It was in May 1834 that the decision was made for Dover to have a railway connecting the town and port with London. Two years later the South Eastern Railway Company (SER) asked Parliament for an Act to build the line. Given Royal Assent on 21 June 1836 but with the proviso that the company would share the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway between London Bridge – the terminus – and Redhill. From there to Ashford was almost straight but there was the major physical obstacle of the cliffs between Folkestone and Dover. It was for this reason that the company bought Folkestone Harbour and turned it into their port of choice for the cross-Channel passage. Nonetheless, on 26 January 1843, the major obstacle – Round Down Cliff – was purposely blown up and the railway to Dover was soon after completed.

Shakespeare Beach, Dover c1840 by James Patterson Cockburn. Note the lay out of the SER railway track on right. Tom Hutton

As part of the Dover Terminus Act, the railway company was allowed to purchase land belonging to Dover Harbour Commission for the station. At the same time they were obliged to pay compensation to the thriving community of shipbuilders on what is now Shakespeare Beach also to the owners of the Mulberry Tree – a popular pub – and a rope factory belonging to J Jones. A considerable number of cottages were demolished, 16 belonging to John Finnis along with his factory for which compensation was paid. However, for those cottagers who were to poor to seek legal help, compensation was not forthcoming. Townsend battery, built in 1779, was demolished along with the Cinque Ports Pilot’s lookout station. The latter was replaced by a highly ornate lookout further to the east. The line, traversing Shakespeare Beach was on trestles.

Proposed Town Station – Architects drawing c 1840

It had been envisaged that the station would be a grandiose structure, but due to lack of money, the final building consisted of a yellow brick building 300-feet long, 30-feet wide and 20-feet high, parallel to the platform for passengers. This was the main entrance containing the booking office and had a tiled roof. A 250-foot extension with an iron roof was erected for use as the waiting rooms, goods and parcel offices and pay offices. Further offices were added to the east, all of poor quality with iron roofs. The original architect’s drawings had been freely available since the project commenced and were used in the publicity material long after the station opened!

In order to counter criticism the company said that the station was only temporary but when it became evident that the structure was permanent, they had a change of tack. The publicity releases stated that the station was ‘ striking by its simplicity particularly in the dark when it was internally lit by gas lights!‘ Between the station and the beach was a turntable and a number of lines on which spare carriages were kept. There were also water tanks, loading wharves and warehouses. The project was said to have cost £29,475 out of which Dover Harbour Commission received £23,500 for the land.

The trestles along Shakespeare Beach. Dover Library

The line was completed by 27 January 1844 and the trial run was hauled by the 2-2-2 steam locomotive number 36 Shakespeare. At 14.00hours on Tuesday 6 February townsfolk and visitors, which included dignitaries from Calais, Ostend, Boulogne, Folkestone, Deal, Ashford and London assembled at New Bridge. The Calais contingent had arrived the previous day on the Beaver and included 33 members of the National Guard of Calais band, resplendent in their military uniform and who joined the town and the military bandsmen to lead the procession. The cavalcade, 6,000 strong, set off at 15.00hours the first reaching the makeshift Dover Station half an hour later. At 16.00hrs, a shrill was heard from the Shakespeare engine pulling four carriages, with SER chairman, Joseph Baxendale (1785-1872), and directors, came into the station. The multitude cheered and a gun salute was fired from Archcliffe Fort.

This was followed by a sumptuous banquet held in the Assembly Rooms, near New Bridge on Snargate Street. Used as a theatre, it was completely stripped of scenery and machinery to make room for the 300 men who celebrated that evening. The gallery was given over to ladies but because they were ‘crammed in’ and wearing hooped skirts found it difficult to partake of the meal! In the speeches that followed it was generally agreed that Dover was the ‘highway of nations’. The final cost of the railway line was estimated to be £3,564,172, two and half times more than originally planned.

South Eastern Railway Company Timetable for Dover – February 1844

The next day the railway opened to public traffic and according to the Railway Times of 24 February, six trains a day were provided in each direction. Between 08.00hrs until 17.30hrs from London and 07.00hrs until 18.50hrs from Dover. The latter gave rise to a number of complaints from passengers that came over from the Continent on the afternoon ferries to Dover. The Company’s response was that they should use the Boulogne-Folkestone ferry services as these did tie in with the train times – an attitude that never altered! Another source of complaint came from third class passengers, for their carriages were open and in consequence, sparks from the engine burned their clothes. It was suggested that to avoid this problem they should travel by first class! However, the Gladstone Act of 1844 required Companies to run ‘Parliamentary Trains’ charging 1pence a mile and with proper seating and protection against the weather. SER, like many other Companies, reluctantly accepted the ruling and by the end of the decade found that the number travelling third class had increased without any wider detriment.

From the South Eastern Railway Guilde 1846 for Court & Co Snargate Street. Dover Library

From the outset, SER showed an interest in attracting tourists to Dover by offering excursion fares to what they described as an ‘otherwise closed district. ‘ In their brochures were pictures of Dover’s more unusual attributes such as the garden of Court’s the wine merchants in Snargate Street. They also introduced ships from Dover to Ostend; the first was the Princess Mary, built by Ditchburn and Mare in 1844. She departed from Dover on Sundays and Thursdays, in the morning, and returned on Tuesdays and Fridays. Two years later, she was transferred to Ramsgate for a short-lived service from there to Ostend following which her home port was moved to Folkestone.

This was because the company’s major interest was the promotion of Folkestone harbour. Following the building of the line to Dover, SER had successfully applied for permission from parliament to build a railway line from London to northeast Kent, called the North Kent Line. By 1846 this was open from Ashford to Margate, Thanet, by way of Canterbury (now Canterbury West station) and Broadstairs. The following year they opened a spur down Sandwich and Deal but discounted the need to join Dover to either Canterbury or Deal. On the west side of the county, SER had opened their North Kent Line as far as Strood going through Greenwich, and Dartford but did not consider it economically worthwhile to join this up with the Margate spur.

To promote Folkestone harbour, in 1844, SER formed a subsidiary, the South-Eastern and Continental Steam Packet Company. This company bought the ships and, typically, offered passage from Folkestone to Boulogne at specially reduced rates for passengers buying a combined sea and rail ticket. When the company won the contract for carrying mail on both their trains and ships through Folkestone, there were major ructions in Dover and led to a move to build another railway line to the town.

Train running alongside Shakespeare Beach c 1840

Accidents on the line were frequent and fatalities were not unknown. Engine driver Jasper Hilyard aged 23 was killed. He had turned off the steam in order to stop the train as it was approaching Croydon station. Looking out he hit his head on one of the columns on the station, lost his balance and fell under the wheels of the train. In 1844, the roof collapsed at London Bridge Edward May, a carpenter, was killed and seven others were injured. Robert Buckley and Aaron Wilkinson were killed when an engine fell from a bridge onto the engine they were driving. Thirty people were injured when a train ran into the back of another as the red light rods had not been placed on the back of the first train. At the subsequent enquiry William Cubbitt (1785–1861), the Company’s senior engineer, accepted that not putting out the red light rods was the cause of most rail accidents.

In February 1846, twelve men William Jordan aged 28, Thomas Hutton aged 52, James Cook aged 56, John Pain aged 39, Israel Hughes aged 28, John Wilson aged 28, John Kendall aged 24, Joseph Hambrook aged 24, John Russell, William Richards, Edward Ruck and Joseph Williams alias Reader, were killed in an explosion at Dover. Ten were married and John Pain left a widow and seven children. There was only one survivor, a Mr Gillham but was seriously injured and unable to give evidence. However, one of the victims did give a clear statement before he died.

Round Down Cliffprior to being blown up on 26 January 1843 – Dover Museum

At the Inquest, presided over by Dover’s coroner George Thompson (d 1860), the jury were told that there were three caves one of which had a door keeping the inside dry, the other two were open to the elements and used as workshops. It was raining and the men, who were working on the line, went into the dry cave to eat their meal – there was no lock on the door. It was dark and one struck a lucifer to light his pipe and let it fall to the ground. As the light fell they saw black powder on the floor and remembered little else.

A subsequent enquiry found that the cave was the one that the gunpowder was stored in that was used to blow up Round Down Cliff. Two unrecorded barrels had been left in the cave. The verdict of accidental death was passed and the company gave 100guineas to a fund set up by George Thompson for the 50 dependants’ left destitute by the accident. After this, all the caves between Folkestone and Dover were searched for gunpowder and other combustibles and they were disposed of by throwing them into the sea.

On 2 April 1848, the foundation stone for the Admiralty Pier was laid. This was the west and first pier of two piers that were to be constructed to form a Harbour of Refuge, but the second was never built. The Admiralty Pier required the demolition of the Pilot’s lookout station that was replaced by a highly ornate lookout further to the east.

Paddle steamer Goliath paying out the Submarine Cable across the Strait of Dover. 28 August 1850 Illustrated London News

The children of the Pier district, where the Station was located, were awe-struck on 28 August 1850 when they saw a horsebox taken into a siding close the Station. Besides a table, chairs, a new fangled apparatus carried in. By the time the Mayor, Steriker Finnis, Charles Walker (1812-1882) the SER’s electrician and Thomas Crampton (1816-1888), a Company engineer, along with other dignitaries arrived that evening, a large crowd had collected. The men said nothing and the door was closed on the assembled throng by which time reporters from London had arrived. What took place in that horsebox that evening was to have worldwide impact. The steamer Goliath accompanied by the Admiralty survey ship Widgeon had laid the first submarine telegraph cable from Dover to Cap Gris Nez! At 21.00hrs that evening, from a temporary building at Cap Gris Nez, France, the world’s first international telegraphed message, using Morse Code, was sent across the Strait and received by the apparatus in the horsebox!

The railway was, by this time, beginning to eclipse coach travel as the best form of transport. Charles Dickens first travelled on a train to Dover when he was going to Paris in 1851, having previously undertaken the journey by mail coach. He was astounded by both the comfort and the speed but asked what has SER ‘done with all the horrible little villages we used to pass through, in the diligence? (A Flight published 1851). Charles Dickens was a frequent guest at the Lord Warden Hotel, located between the station and the harbour. Engineer, Thomas Crampton besides proving his engineering skills with the laying of the Channel submarine cable was employed by SER to design locomotive engines. He designed and built ten and No136 Folkestone, was on show at the Great Exhibition of 1851.

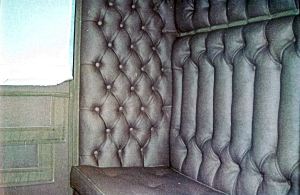

Lord Warden Hotel showing the walkway to Dover Town Station. Nick Catford

Part of the plans for the Dover station – in 1863 renamed Town Station – had included a terminus hotel and this was eventually built on the land originally designated for the station. Designed by Samuel Beazley (1786-1851), it was named after the Lord Warden 1829-1852 – the Duke of Wellington (1769-1852) – who had actively promoted the railway. The hotel opened on 7 September 1853 and although both were dead, everyone raised their glasses to the Duke of Wellington and Samuel Beazley. The hotel was aimed at the wealthier cross-Channel travellers and from the first floor, there was a covered walkway to the Town Station.

South Eastern Railway c1850s soldiers ticket Dover to Folkestone Junction. Michael Stewart Collection

By this time, Edmondson’s railway tickets had been introduced. These were named after Thomas Edmondson (1792-1851), a trained cabinetmaker, who became a stationmaster on the Newcastle & Carlisle Railway. His tickets, a card about 1inch x 2inches, on which the name of the station, destination and the number printed. They were date-stamped in the booking office when issued and different colours and patterns were used to distinguish the different type of tickets. Not long after they were introduced on SER they played a crucial role in bringing the Great Bullion Robbers to justice. This took place on the down mail train from London Bridge to Dover on 15 May 1855. The use of Edmondson tickets, by British Rail, ceased in February 1989.

The first part of the Admiralty Pier was finished by 1854 and fully completed in 1871. On 1 September 1854, the Admiralty agreed that passenger trains would be allowed on to the Pier and in 1861 the SER were running trains along it. From the outset, SER had the lucrative government mail train and passage contract at Folkestone. When, in 1853, the Mail Packet Service from Dover was to be transferred from the Admiralty to private contractors they expected that they would get it. However, it went to Messrs Jenkins and Churchward and SER virtually turned its back on Dover.

Admiralty Pier foundation stone laid in 1848 came into use in 1854 and fully completed in 1871. SER trains ran along the Pier from 1861.

In 1861 the London, Chatham and Dover Railway (LCDR) opened their line from London through to the Harbour Station on nearby Elizabeth Street. Although adjacent to the harbour, passengers had to walk along Admiralty Pier to reach the ferries. SER buried their pride and moved the Princess Clementine, an iron paddle steamer built by Laird Brothers and launched in 1846, together with the Princess Maud, built by Ditchburn and Mare and launched in 1844, from Folkestone to Dover. The ships plied between Dover and Ostend but the service was short-lived ceasing in April 1862.

At the outset SER’s, main terminus for Dover passengers, in the City, was London Bridge Station, which they shared with the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway. The Station was actually two stations in close proximity to each other. SER had their station rebuilt to a design by Samuel Beazley opening in 1850. Following the arrival of LCDR, the company bought the site of Hungerford Market and commissioned Sir John Hawkshaw (1811-1891) to build a central London station and this opened on 11 January 1864. Named Charing Cross Station, like London Bridge Station, it was on the north side of the Thames and in January 1869, they opened Waterloo Junction Station, opposite on the south side of the Thames.

LCDR petitioned Parliament to run their trains along Admiralty Pier and from 1864 they had their wish. In the meantime in 1863, they won the converted Mail Packet contract for Dover! Although the two companies, with the blessing of Parliament, entered into the Continental Agreement, whereby all railway receipts appertaining to the Channel Passage ports between Margate and Hastings, were pooled and then divided in agreed portions between the two companies. However, SER continued to promote Folkestone and built an attractive new Shorncliffe station (now Folkestone West) at Cheriton, which was outside of the Agreement area.

By 1875, LCDR had a fleet of cross Channel packet ships running out of Dover and although the Continental Agreement had fallen into abeyance, Sir Edward proposed a quasi merger between the two railway/packet companies, whereby there would be a fusion of the net profits of both companies, for an interchange of traffic and a friendly working relationship. At the time James Staats Forbes (1823-1904) who was the Chairman of LCDR was ill, but on his recovery made it clear that he was not happy with the proposed arrangement and the proposal fell through.

Sir Edward immediately turned his attention to excavating a Channel tunnel in order to have a through line from London to Paris. Working in conjunction with the Nord Railway, SER formed the Submarine Continental Railway Company and worked started at the foot of Shakespeare Cliff, next to where Round Down Cliff had once been. A 22.55 metre shaft was sunk and a level heading driven for 792.68 metres. A second heading was driven for 1,944 metres under the sea. Sir Edward planned to run a railway line to St Margaret’s, on the east side of Dover, and bought Pencester Meadow in order to build a railway station in the centre of Dover. In 1878, SER installed a 60-lever signal box adjacent to the Town Station in preparation.

Dover Colliery opened on the site of the first Channel Tunnel now Samphire Hoe. Bob Hollingsbee Collection

However, a Joint Committee of both Houses of Parliament held an enquiry, in July 1883, into the proposed tunnel and declared that: ‘The majority of the Committee are of the opinion that it is not expedient that Parliamentary sanction should be given to a submarine communication between England and France.’ Following the failure of the Channel tunnel proposal, William Crundall senior re-purchased the Pencester site making a nice profit. Close to the Watkin borings, a site was created out of spoil from the present Channel Tunnel working and in 1994, the site was officially named Samphire Hoe. The White Cliffs Countryside Partnership (WCCP) runs this very popular visitor attraction.

Coal had been found across the Channel, near Calais and a borehole was sunk at the bottom of the abandoned Channel Tunnel shaft. Coal was found at a depth of just over 300 metres and under the supervision of Francis Brady, the Chief Engineer of the Railway Company, drilling was started and eventually Shakespeare Colliery opened. During this time a halt, near the site, was built. In June 1886, SER opened a halt on the Warren, between Folkestone and Dover, but failed to gain the consent of the Board of Trade. The company was forced to close the halt until they met specified criteria. It was a long time before the Board of Trade was entirely happy, in fact, the halt was not officially opened until 1 June 1908 and thereafter not very often.

One of the problems that SER constantly faced was that from Folkestone to Dover the tracks were – and still are – in close proximity to the cliffs and sea. These days there are many safe guards and safety warnings but in the 19th century, such gadgetry was not available. On 14 November 1875, there was a severe storm that wrecked groynes severely damaged the Town station roof and the track was flooded. By the beginning of 1876, the weather was so bad that a storm damaged Admiralty Pier and cost £26,000 to repair. The damage to SER ships, berthed in Folkestone, was estimated at £2,000 and as the storms did abate, the cliffs between Folkestone and Dover started to give way. LCDR, helped out by accepting SER passengers travelling to Dover, on their trains. As the wet stormy weather continued sections of the LCDR line between Dover and Canterbury became vulnerable to collapse and so LCDR diverted their packet ships to Folkestone and SER trains carried the mail for them.

This gave Sir Edward the impetus to make Forbes, LCDR’s chairman, an offer to amalgamate. Watkins set out a time table for talks, sending an appropriate Bill to parliament with a view for the resultant Act to be given Royal Assent two years after. The proposal was put to the LCDR Board, who generally endorsed but in negotiation, the terms were not acceptable and the proposal fell through. Shortly after LCDR opened a steam packet service to Flushing, now Vlissingen in southern Netherlands. Later, SER countered this by opening a new cross Channel route via Port Victoria, also near Queenborough and years of litigation ensued.

Sir Edward Watkin (in a Cossak hat) and the SER Board members at the re-opening of the Dover-Folkestone railway line following the 1877 landslip. Dover Library.

In January 1877 a severe storm washed away the foot of the cliff at the eastern end of the Martello Tunnel, on the line between Dover and Folkestone. This had brought down some 60,000tons of the chalk cliff, killed three workers and completely blocked the line. Forbes of LCDR reacted by offering SER the use of the whole of the LCDR railway lines saying that ‘We are partners … take your mails over our railway.’ For the following two months, until the line was repaired, SER trains carrying mails for Belgium, went from London to Beckenham on the SER line and from there on the LCDR line to Dover. However, a rumour spread that SER would not be re-opening the railway line between Folkestone and Dover. The rumour was attributed to LCDR and therefore Sir Edward arranged an official re-opening of the line. For this, he wore a Cossak style hat and with his retinue, arrived on a Cudworths 2-4-0 Class E locomotive with a stovepipe chimney.

It had been hoped that the venue for the annual Volunteer Review of 1883, held over the Easter weekend, would be Dover. However, the Hon. Secretary of Commanding Officers wrote to say that it would be in Brighton. The reason cited was that neither of the two railway companies had replied to their communication concerning special trains. Dover council were angry and the Mayor, Rowland Rees wrote a terse letter, saying that over the previous ten years the number of cross-Channel passengers, going through Dover, had fallen. He went on to say the following the Bank Holidays Act of 1871 the council had launched an expensive tourism initiative to persuade people to come to Dover and for those travelling across to the Continent, to stop over. In support of this initiative, private horse driven omnibus companies were prepared to collect passengers and return them to the terminus and that since 1881 Back’s Omnibus had been running a regular service between the Town Station and Buckland Bridge, calling at the Harbour Station.

Duke & Duchess of Connaught welcomed at Town Station – 14.07.1883

The town’s Member of Parliament, Major Alexander Dickson (1834-1889), was a managing director of LCDR and on being informed of why the Volunteer Review was not being held in Dover, was angered and at his railway company’s behaviour. That summer LCDR introduced excursion trains from London to Dover and SER quickly responded with similar offers. Then on 14 July 1883, SER was given the greatest fillip of all. The Duke and Duchess of Connaught chose the Town Station to arrive when they came to open Connaught Hall and Connaught Park!

A Parliamentary Bill was put forward, in 1890, proposing a joint Board for the management of SER and LCDR for a period of ten years. The proposal suggested that there would be a division of profits and the new Board would sanction the provision of new capital in specified proportions. As the Bill was going through parliament, Dover Mayor, William Adcock, and council together with the Chamber of Commerce, presided over by Richard Dickeson, pledged to secure guarantees for equitable fares and rates and sufficient service of trains. However, due to the animosity between the chairmen of the two railway companies the Bill was dropped.

In March 1892 SER were awarded the contract for the conveyancing mail on the railway worth £25,000. LCDR’s contract was only worth £2,275 and Sir Edward celebrated. However, within two months, in May 1892, a blaze broke out at the Town Station destroying all the offices. While the fire was still raging, two boat trains ran through the station! Following the fire, repairs were undertaken but about twelve months later the roof over one platform collapsed. This caused a carriage to be de-railed, which smashed into a pillar, but luckily, no one was hurt. Investigations showed that the fire had weakened the roof and the accident happened due to inadequate repairs brought about by cost cutting.

South Eastern Railway ceased to exist on 1 January 1899

On 6 September 1897, Dover became the first town to have a municipally owned tramway system and this ran from the town centre to the Pier District, close to the railway stations. Six years before, in 1891, the Dover Harbour Board, with the full backing of the council and the Chamber of Commerce, applied for an Act of Parliament for the construction of a Commercial Harbour. In 1895, this was upgraded to the Admiralty Harbour and it was quickly recognised that on completion it was likely to turn Dover into a major port. In 1894, Sir Edward Watkin retired and four years later, his major adversary, James Staats Forbes retired. The two railway companies sort Parliamentary approval for a joint Management Committee. Although strongly opposed by the Trade Union Congress (TUC), the South Eastern and London, Chatham and Dover Railway Companies Act of 5 August 1899 confirmed the formation of the South Eastern and Chatham Railway Companies (SECR) that came into operation on 1 January 1899.

Railway ticket from Dover to Shakespeare Colliery post 1899 . Michael Stewart Collection

The miners’ strike of 1912 began in March that year and continued to the end of April creating a national fuel shortage. Railway services were hit and the Town Station closed. The cross Channel ships were concentrated at Dover but coaled up in Calais. Two years later, due the expected opening of Marine station, Town station was officially downgraded. This occurred on 14 October 1914, ten weeks after World War I was declared on Tuesday 4 August. In the event, Marine Station was commandeered and the Town Station was used as an ambulance station for dealing with the seriously injured returning from the Frontline.

SECR Line from Folkestone Harbour to Dover 1914. Alan Young Disused-stations.org

On 19 December 1915, a landslide completely blocked a mile of track between the Martello and Abbots Cliff tunnels. A train, on the track at the time, was derailed but luckily, no one was injured and the passengers and crew walked back to Folkestone Junction. SECR after consultation with the Board of Trade decided that the blockage could not be removed during the War. Thus, passengers that wished to travel from Folkestone to Dover were faced with a long arduous journey for Dover was under military rule and they could not enter the town except by rail. Thus they had to leave Folkestone on the Elham Valley Line to Canterbury then back to Dover on the old LCDR line. For the remainder of the War the Admiralty used the tunnels to store mines and shells for locally based warships and the Town Station became a mortuary.

Town Station after being taken over by the Marine Department. Dover Library

The reopening of the line between Dover and Folkestone took place on 11 August 1919 the line having been reconstructed during the spring and early summer. Except for the part used as mortuary the Town Station was closed. It was decided to convert the portion nearest the Lord Warden Hotel into offices for the Marine Department. The engine sheds from Priory Station were moved onto the site and in September 1920, the rear of the Town Station was turned it into a lock-up garage, complete with petrol pumps!

SECR became part of Southern Railway that came into operation on 1 January 1923. The Marine Department offices at the old Town Station were converted into offices for the operating staff of the Eastern Division who were responsible for 744 miles of railway. Another part of the old station was demolished. Three years, in February 1926 work started on the construction of a seawall using rubble created by the levelling part of Archcliffe Fort.

Former Dover Town Station late1920s. Archcliffe Fort on the right. Nick Catford

The old four-line railway track was replaced and by Act of Parliament, the footbridge spanning the railway to a promenade on Shakespeare Beach connected with the then landward side footpath. New engine sheds were built nearby and were opened on 9 November 1929. A large coaling tip was erected and what remained of the Town Station was demolished except for the offices. In October 1934 the Southern Railway Marine Department Divisional were moved from Admiralty House, on Marine Parade, back to their original offices in the old Town Station!

Centenary celebrations of the Opening of the South Eastern Railway – Dover Express 11.02.1944

In February 1944, during the dark days of World War II (1939-1945), a centenary celebration of the railway coming to Dover was held at the Maison Dieu. Opened by Dover’s Member of Parliament, Colonel John Jacob Astor, the exhibition was an upbeat affair looking forward to a positive future for Dover’s railway connections. Albeit, post World War II developments finally saw the end of what was left of the Town Station. The desolate site is used as a lorry/ car park. A sad ending to what was Dover’s first railway station.

Town Station site today with the Tornado in foreground. Alan Sencicle 2009.

For more information:

www.disused-stations.org.uk